Royal Malaysian Navy

The Royal Malaysian Navy (RMN, Malay: Tentera Laut Diraja Malaysia; TLDM; Jawi: تنترا لاءوت دراج مليسيا) is the naval arm of the Malaysian Armed Forces. RMN is the main agency responsible for the country's maritime surveillance and defense operations. RMN's area of operation consists of 603,210 square kilometers covering the country's coastal areas and Exclusive Economic Zones (EEZ). RMN also bears the responsibility of controlling the country's main Sea Lines of Communications (SLOC) such as the Straits of Malacca and the Straits of Singapore and also monitors national interests in areas with overlapping claims such as in Spratly.

History

Straits Settlement Royal Naval Volunteer Reserve

The Royal Malaysian Navy can trace its roots to the formation of the Straits Settlement Royal Naval Volunteer Reserve (SSRNVR) in Singapore on 27 April 1934 by the British colonial government in Singapore. The SSRNVR was formed to assist the Royal Navy in the defence of Singapore, upon which the defence of the Malay Peninsula was based. Also behind its formation were political developments in Asia, particularly the rise of a Japan that was increasingly assertive in Asia. In 1938, the SSRNVR was expanded with a branch in Penang. On 18 January 1935, the British Admiralty presented Singapore with an Acacia-class sloop, HMS Laburnum, to serve as the Reserve's Headquarters and drill ship. It was berthed at the Telok Ayer Basin. HMS Laburnum was sunk in February 1942, prior to the capitulation of Singapore at the beginning of Second World War activities in the Pacific.

With the outbreak of the Second World War in Europe, the SSRNVR increased the recruitment of mainly indigenous personnel into the force, to beef up local defences as Royal Navy resources were required in Europe. Members of the SSRNVR were called up to active duty, and the force was augmented by members of the Royal Navy Malay Section. This formed the basis of the navy in Malaya, called the Malay Navy, manned by indigenous Malay personnel. (Similarly, the Malays were recruited into the fledgling Malay Regiment formed in 1936). The Malay Navy had a strength of 400 men who received their training at HMS Pelandok, the Royal Navy training establishment in Malaya. Recruitment was increased and in 1941 at the outbreak of the war in Asia, the Malay Navy had a strength of 1,450 men. Throughout the Second World War, the Malay Navy served with the Allied Forces in the Indian and Pacific theatre of operations. When the war ended with the Japanese Surrender in 1945, only 600 personnel of the Malay Navy reported for muster. Post war economic constraints saw the disbandment of the Malay Navy in 1947.

After world war II – Formation of the Malayan Naval Force

The Malay Navy was reactivated on 24 December 1948 at the outbreak of the Malayan Emergency, the communist-inspired insurgent war against the British colonial government. The Malayan Naval Force (MNF) regulation was gazetted on 4 March 1949 by the colonial authorities, and was based at an ex-Royal Air Force radio base station in Woodlands, Singapore. The base was called the 'MNF Barracks' but was later renamed HMS Malaya. The Royal Naval Volunteer Reserve (RNVR) was reconstituted as a joint force comprising the Singapore Division and the Federation Division, by an Ordinance passed in Singapore in 1952.[4] The main mission of the Malayan Naval Force (MNF) was coastal patrols to stop the communists receiving supplies from the sea. In addition, the Force was tasked with guarding the approaches to Singapore and other ports. The MNF was equipped with a River-class frigate, HMS Test, which was used as a training ship. By 1950, the MNF fleet had expanded to include the ex-Japanese minelayer HMS Laburnum, Landing Craft Tank (LCT) HMS Pelandok ("Mousedeer"), motor fishing vessel HMS Panglima ("Marshal"), torpedo recovery vessel HMS Simbang and several seaward defence motor launches (SDML). In August 1952, Queen Elizabeth II bestowed the title "Royal Malayan Navy" on the Malayan Naval Force in recognition of its sterling service in action during the Malayan Emergency.

Independence

.svg.png.webp)

.svg.png.webp)

On 12 July 1958, soon after attaining its independence on 31 August 1957, the Federation of Malaya negotiated with the British government to transfer British naval assets to the newly formed Royal Malayan Navy. With the hoisting of the Federation naval ensign – the White Ensign modified by the substituting the Union Flag with the Federation flag in the canton – the Royal Malayan Navy became responsible for Malaya's maritime self-defence. The "Royal" in Royal Malayan Navy was now in reference to the Yang di-Pertuan Agong, who became the Supreme Commander of the Malaysian Armed Forces. All ships, facilities, and personnel serving in the Royal Malayan Navy were inherited by the Malayan government. The new force had an operational and training base at HMMS Malaya, and a small coastal fleet of one LCT, one coastal minelayer, six Ham-class minesweepers and seven Ton-class minesweeper (the ex-RN 200th Patrol Squadron) on transfer from the Royal Navy.

On 16 September 1963, the naval force was renamed the Royal Malaysian Navy (RMN), following the formation of Malaysia. Eighteen Keris-class were ordered from Vosper, and formed the mainstay of the navy for years to come. These 103 ft (31 m) boats were driven by Maybach diesels and capable of 27 knots (50 km/h; 31 mph). The Keris patrol boats were confined to coastal patrols and had short endurance. An offensive capability was acquired with the purchase of four Brave-class patrol boats also known as Perkasa-class patrol boats in RMN service. The Perkasa patrol boats were built for the RMN by Vosper Thorneycroft in 1967, powered by three Rolls-Royce Marine Proteus gas turbines as the main power plant with two diesel auxiliary engines for cruising and manoeuvring. These were armed with four 21-inch (53 cm) torpedoes, one Bofors 40 mm gun forward, and one 20 mm cannon aft. They had a maximum speed of 54 knots (100 km/h) and was driven by triple propellers. The Royal Navy transferred the Loch-class frigate HMS Loch Insh to the RMN in 1964 and renamed KD (Kapal Di-Raja, "His Majesty's Ship") Hang Tuah. In 1965, during the Indonesian confrontation, Hang Tuah took over guardship duties off Tawau from HMAS Yarra. The ship served as the flagship of the RMN until it was decommissioned in the 1970s and scrapped. The RMN also used some of the decommissioned ship as a part of navy monument. This shop can be toured at Bandar Hilir, Melaka or at the Lumut Naval Base.

Malaysianisation

_underway_c1962.jpg.webp)

Following the end of Indonesian confrontation in 1966, Tunku Abdul Rahman and his colleagues decided to Malaysianise the top posts in the navy and air force. They offered these posts to two senior Malaysian army generals, who declined for two main reasons. First they felt that they were not professionally qualified and second because they did not want to jeopardise their own careers in the army. Tunku and his colleagues then decided that they would select two officers, one from the navy and one from the air force, and appoint them chiefs of their respective services. They were fully aware of Rear Admiral Datuk K. Thanabalasingam's age —he was 31 years old and a bachelor- but decided to appoint him and take the risk. Under Thanabalasingam and with Tunku Abdul Rahman's foresight and will, they were responsible for initiating the gradual transformation of the navy from a coastal navy (brown water force) to a sea-going navy (green water navy).

1970s onwards

In 1977, the RMN acquired the frigate HMS Mermaid from the Royal Navy to replace the decommissioned Hang Tuah. The ship was also named KD Hang Tuah, but retained HMS Mermaid's pennant number of F76. Hang Tuah is a 2,300 standard ton light patrol frigate armed with twin 102 mm guns. Hang Tuah gradually reverted to a training role and continues in that role for the RMN. KD Rahmat (ex-Hang Jebat) (F24) joined the RMN in 1972. The 2,300-ton ship was a one-off Yarrow light frigate design for the RMN. The ship was originally named Hang Jebat but renamed after initial propulsion problems during pre-commissioning trials. It was the first Malaysian naval vessel equipped with a missile (Seacat) system. Rahmat was decommissioned in 2004.

The RMN purchased several types of missile boats in the 1970s and 1980s. These were four Perdana-class missile boats purchased from France and four Handalan-class missile boats purchased from Sweden. Both classes were armed with the Exocet MM38 missiles. The RMN also acquired two 1,100-ton Musytari-class offshore patrol vessels of Korean design. Sealift requirements were met by the purchases of several ex-United States Navy World War II-era LSTs. KD Sri Langkawi (A1500), ex-USS Hunterdon County, KD Sri Banggi (A1501), ex-USS Henry County, and KD Rajah Jarom (A1502), ex-USS Sedgwick County, were replaced by KD Sri Indera Pura (1505), the Newport-class LST ex-USS Spartanburg County. Additional sealift capability is provided by two 4,300-ton, 100-metre support ships, KD Sri Indera Sakti (1503) and KD Mahawangsa (1504). Minehunting capabilities are provided by four Mahamiru-class minehunters. These are Italian-built ships based on the Lerici-class but displacing 610 tons. Hydrographic duties are handled by KD Perantau and KD Mutiara. A Naval Air Wing was also founded with the purchase of ex-Royal Navy Westland Wasps. Some ships of the RMN that have been decommissioned was transferred to the Malaysian Maritime Enforcement Agency (MMEA). MMEA had received more than 20 vessels from the RMN fleet to equip its enforcement operations from 2000s onwards.[5]

Modernisation

_and_KD_Jebat(FFG29)_with_USS_George_Washington_(CVN_73).jpeg.webp)

The modernisation of the RMN began in the late 1980s. Four Laksamana-class corvettes were purchased from Italy. These compact ships were originally built for Iraq, but were not delivered due to international sanctions put in place against Iraq. A prominent addition to the fleet were two Lekiu-class frigates. Based on the Yarrow F2000 design, the two 2,300-ton frigates are armed with Exocet MM40 II SSM and the Sea Wolf VLS point defence SAM system with accommodation for one Westland Super Lynx helicopter.[6] Malaysia had planned to add new batch of Lekiu frigates but this was cancelled in August 2009. Complementing the two Lekiu frigates are two German-built Kasturi-class corvettes which were delivered in the early 1980s. Two Scorpène-class submarines were ordered by the RMN on 5 June 2002 under a €1.04 billion (about RM4.78 billion) contract to form the new submarine force.[7] RMN also purchased six Kedah-class offshore patrol vessels and a batch of Keris-class littoral mission ships to boost the fleet. In addition, the construction of six new Maharaja Lela-class frigate also will make the RMN as a formidable power in the region.

Anti-piracy efforts

The Royal Malaysian Navy has been patrolling the Gulf of Aden to thwart piracy since 2009.[8] In January 2011, the navy foiled a hijacking attempt against the Malaysian-flagged chemical tanker MT Bunga Laurel carrying lubricating oil and ethylene dichloride.[9][10] The navy ship KA Bunga Mas 5 responded after receiving a distress signal from the ship. A Fennec attack helicopter was used to pin down the pirate mothership as commandos boarded the tanker. The commandos injured three pirates in the battle to re-take the ship. 23 sailors were rescued and seven Somali pirates were detained. According to an 11 February 2011 online breaking news update by CNN's Brad Lendon, the seven Somalis, including three boys under 15 years old, could face the death penalty if convicted on charges of firing on Malaysian armed forces- navy commandos- while attempting to hijack the ship. The seven was sentenced for four to seven years in prison by Malaysian High Court on 2 September 2013.[11] The ship was rescued 555 kilometres (300 nmi; 345 mi) from the coast of Oman.[12][13]

The Royal Malaysian Navy was also involved in the operation to secure the release of MT Orkim Harmony that was hijacked in 2015 by a group of Indonesian pirates. All of the pirates were captured with the help of Vietnam Border Guard (VNBG), Vietnam Coast Guard (VNCG),[14] Royal Australian Air Force[15] and the Indonesian Navy.[16]

Sulu militants intrusion on Sabah

Following the Sulu militants' intrusion, a military standoff lasted from 11 February 2013 until 24 March 2013[17] after 235 militants, most of whom were armed,[18] arrived by boats in Lahad Datu, Sabah, Malaysia from Simunul island, Tawi-Tawi in the southern Philippines on 11 February 2013.[19][20][21] The group, calling themselves the "Royal Security Forces of the Sultanate of Sulu and North Borneo", was sent by Jamalul Kiram III, one of the claimants to the throne of the Sultanate of Sulu.[19] Kiram stated that their objective was to assert the unresolved territorial claim of the Philippines to the eastern part of Sabah (which is the former North Borneo).[22]

Malaysian security forces surrounded the village of Tanduo in Lahad Datu where the group had gathered and, after several weeks of negotiations and broken deadlines for the intruders to withdraw, security forces moved in and routed the militants. The Royal Malaysian Navy enforced a naval blockade during and after the standoff to ensure that no more Sulu militants would be able to reach Sabah. The assets allocated for the blockade included KD Jebat, KD Perak, KD Todak, among many others. The RMN also provided a naval special warfare unit for joint operations with army, air force and police commandos to track down and neutralise any militants left after the standoff.

Commanders

List of chiefs of the Royal Malaysian Navy

Source.[23]

| No | Name | Term Began | Term Ended |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Commodore Edward Dudley Norman | 15 May 1957 | 7 February 1960 |

| 2 | Captain W.J. Dovers | 8 February 1960 | 13 July 1962 |

| 3 | Commodore A.M. Synnot | 14 July 1962 | March 1965 |

| 4 | Commodore A.N. Dollard | March 1965 | 30 November 1967 |

| 5 | Rear Admiral Tan Sri Dato' Seri K. Thanabalasingam | 1 December 1967 | 31 December 1976 |

| 6 | Vice Admiral Dato' Mohammad Zain Mohammad Salleh | 1 January 1977 | 31 Januari 1986 |

| 7 | Vice Admiral Tan Sri Abdul Wahab Hj Nawi | 1 February 1986 | 31 October 1990 |

| 8 | Vice Admiral Tan Sri Mohammad Shariff Ishak | 1 November 1990 | 12 October 1995 |

| 9 | Vice Admiral Tan Sri Ahmad Ramli Hj Mohd Nor | 13 October 1995 | 14 October 1998 |

| 10 | Admiral Tan Sri Dato' Seri Abu Bakar Abdul Jamal | 14 October 1998 | 12 August 2002 |

| 11 | Admiral Datuk Mohammad Ramly Abu Bakar | 13 August 2002 | 12 August 2003 |

| 12 | Admiral Tan Sri Dato' Seri Mohd Anwar Mohd Nor | 13 August 2003 | 27 April 2005 |

| 13 | Admiral Tan Sri Ilyas Hj Din | 28 April 2005 | 14 November 2006 |

| 14 | Admiral Tan Sri Ramlan Mohamed Ali | 15 November 2006 | 31 March 2008 |

| 15 | Admiral Tan Sri Dato' Seri Abdul Aziz Hj Jaafar | 1 April 2008 | 18 November 2015 |

| 16 | Admiral Tan Sri Ahmad Kamarulzaman Hj Ahmad Badaruddin | 18 November 2015 | 29 November 2018 |

| 17 | Admiral Tan Sri Mohd Reza Mohd Sany | 30 November 2018 | 27 January 2023 |

| 18 | Admiral Datuk Abdul Rahman Hj Ayob | 27 January 2023 | current |

Admiral Tan Sri Ramlan Mohamed Ali in Spain.

Admiral Tan Sri Ramlan Mohamed Ali in Spain._CNS_exchanging_mementos_with_Vice_Admiral_HCS_Bisht%252C_FOCINC_EAST.jpg.webp) Admiral Tan Sri Ahmad Kamarulzaman Hj Ahmad Badaruddin in India.

Admiral Tan Sri Ahmad Kamarulzaman Hj Ahmad Badaruddin in India.

Ranks

Sleeve insignia were similar from those of the Royal Navy, but rarely used especially foreign visits.

| Rank group | General/flag officers | Senior officers | Junior officers | Officer cadet | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

.svg.png.webp) |

.svg.png.webp) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Laksamana armada | Laksamana | Laksamana madya | Laksamana muda | Laksamana pertama | Kepten | Komander | Leftenan komander | Leftenan | Leftenan madya | Leftenan muda | Pegawai kadet kanan | Pegawai kadet | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

The Sultan of Selangor, as Commodore-in-Chief of the RMN, holds the rank of Honorary Rear Admiral and as such wears a normal Rear Admiral's uniform.

| Rank group | Senior NCOs | Junior NCOs | Enlisted | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

No insignia | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Pegawai waran I | Pegawai waran II | Bintara Kanan | Bintara Muda | Laskar Kanan | Laskar Kelas I | Laskar Kelas II | Perajurit Muda | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Warrant officer class I | Warrant officer class II | Chief petty officer | Petty officer | Leading rate | Able rate | Junior able rate | Seaman recruit | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Squadrons

- Squadron Submarine

- Squadron 23rd Frigate

- Squadron 22nd Corvette

- Squadron 24th Corvette

- Squadron 17th PV

- Squadron 11th LMS

- Squadron 1st FAC

- Squadron 2nd FAC

- Squadron 6th FAC

- Squadron 13rd PC

- Squadron Fast Troop Vessel

- Squadron 26th Mine Counter Measure Vessel

- Squadron 31st MPCSS

- Squadron 32nd Sealift

- Squadron 36th Hydro

- Squadron 27th Training Vessel

- Squadron Diving Tender

- Squadron Tug

- Squadron 501st Super Lynx

- Squadron 502nd Fennec

- Squadron 503rd AW139

- Squadron 601st UAS

Fleets

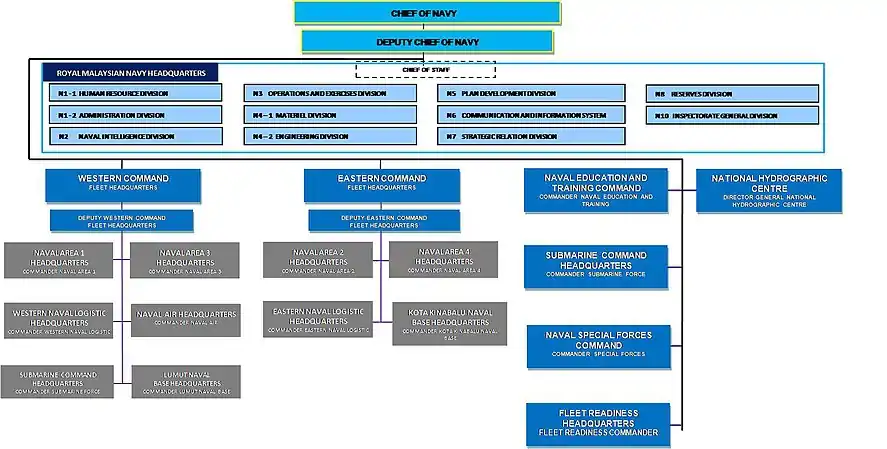

Royal Malaysian Navy have two main fleets:

- Western fleet (In Malay: Armada Barat)

- The fleet HQ was at Lumut Naval Base, Lumut, Perak. The chief of the fleet is Vice Admiral Datuk Abu Bakar bin Ajis.

- Eastern fleet (In Malay: Armada Timur)

- The fleet HQ was at Sepanggar Naval Base, Sepanggar, Sabah. The chief of the fleet is Vice Admiral Dato' Sabri bin Zali.

Bases

The RMN's Fleet HQ is called KD Malaya, in Lumut, Perak. Other bases are located at Tanjung Gelang, Kuantan, Pahang, which also serves as HQ Naval Region I and KD Sultan Ismail at Tanjung Pengelih, Johor, where the Recruit Training Centre is located. Bases are also located in Sandakan, Sabah. The principal submarine base is located at Sepanggar, Sabah, which also serves as HQ Naval Region II.

Another base is also being constructed on Pulau Langkawi, Kedah to provide the RMN with readier access into the Indian Ocean. Ready access into the Pacific Ocean is available via the existing base at Labuan and Semporna, Sabah.

Peninsular Malaysia

- RMN Lumut Naval Base, Lumut, Perak (HQ Western Fleet and location of Boustead)

- TLDM Tanjung Gelang, Kuantan, Pahang (HQ Naval Region I)

- TLDM Tanjung Gerak, Langkawi, Kedah (HQ Naval Region III) (KD Badlishah)

- TLDM Tanjung Pengelih, Johor (Recruit Training Centre) (PULAREK) (KD Sultan Ismail)

- National Hydrographic Centre, Pulau Indah, Selangor (KD Sultan Abdul Aziz Shah)

- TLDM Sungai Lunchoo, Johor Bahru, Johor (KD Sri Medini)

East Malaysia

- TLDM Sepanggar, Kota Kinabalu, Sabah (HQ Eastern Fleet and HQ Submarine Force)

- TLDM Labuan, Federal Territory

- TLDM Sandakan, Sabah (HQ Naval Region II)

- TLDM Semporna, Sabah

- TLDM Kuching, Sarawak

- TLDM Bintulu, Sarawak (construction confirmed)[26]

- Tun Sharifah Rodziah Sea Base, Semporna, Sabah (a decommissioned oil rig that were retrofitted into a permanent sea base)

Offshore bases

The Royal Malaysian Navy's five naval stations were originally built on outlying atolls, with the most developed Station Lima now expanded to a comfortably habitable naval station and also a popular diving spot in the region, in contrast with its harsh original conditions in 1983. On 21 June 1980 a claim plaque was erected on the island and three years later eighteen PASKAL men went ashore in May 1983 to build the first encampment while braving the elements. At the time, the only infrastructure available was a helipad for personnel transfer and the sailors had to camp under the open skies on the bare reef. When the naval station proper was constructed six years later with the construction of a small living-cum-operations quarters, it was also decided that the enlarged island the atoll had become would also be developed as a tourist attraction so that the tourism potential of the island could be exploited.

Thus by 1995, more buildings were added, including two air-conditioned accommodation blocks, an aircraft landing strip, two hangars, a radar station, an air traffic control tower, watchtowers and a jetty. The aviation facilities on the island allow the operation of C-130 Hercules transport planes and CN-235 maritime patrol aircraft operated by the Royal Malaysian Air Force. These facilities made the island a proper island station code-named Station Lima. Patrols by navy soldiers in CB90 attack vessels and larger patrol boats such as the Kedah-class offshore patrol vessels are carried out around the island. The Royal Malaysian Air Force also operate frequently on the airstrip. Several anti-ship and anti-aircraft guns are placed on several areas on the island and the RMAF personnel operate a Starburst air defence system to prevent low-level air attacks. The rest of the stations were originally floating barge type habitat modules constructed on mainland Malaysia. Location selection and module positioning was done during high tide so that they could be more easily anchored during low tide and after found satisfactory, the modules were landed and filled in with cement and rocks to strengthen their anchorages. They are all also equipped with radar and ship docking facilities as well as water and power generation facilities. Soldiers are stationed on all stations.

Offshore stations

- 1983 Station Lima (Swallow Reef)

- 1986 Station Uniform (Ardasier Reef)

- 1986 Station Mike (Mariveles Reef)

- 1999 Station Sierra (Erica Reef)

- 1999 Station Papa (Investigator Shoal)

Special forces

The special forces of the RMN is known as PASKAL (Pasukan Khas Laut or Naval Special Warfare Forces). In peacetime, the unit is tasked with responding to maritime hijacking incidents as well as protecting Malaysia's numerous offshore oil and gas platforms. Its wartime roles include seaborne infiltration, sabotaging of enemy naval assets and installations, and the defence of RMN vessels and bases. This unit is analogous to the United States Navy SEALs. On 15 April 2009, PASKAL was renamed KD Panglima Hitam (KD being the equivalent of HMS in the Royal Navy). The ceremony was held at the RMN Lumut Naval Base to honour PASKAL's courage and loyalty to the nation. Panglima Hitam was the name given to brave and loyal Malay warriors who served during the golden age of the Malay Rulers (Sultans and Rajas) of Perak, Selangor, Johor and Negeri Sembilan.[27]

Equipment

Present development

Following the completion of the New Generation Patrol Vessel (NGPV) program, RMN now moved to the next program called Second Generation Patrol Vessel (SGPV). RMN also planned to purchase a batch of Littoral Mission Ship (LMS) and Multi Role Support Ship (MRSS). As part of the modernisation plan, RMN launches the upgrade program and Service Life Extension Program (SLEP) for the old navy's ship.

Kedah-class New Generation Patrol Vessel

In 1996, the RMN planned to acquire a total of 27 New Generation Patrol Vessels (NGPV) to full fill its future requirement. The German Blohm + Voss MEKO 100 based design was selected and a contract of six NGPVs was signed in 2003. However, due to management failure of the main contractor, PSC-Naval Dockyard Sdn Bhd (PSC-ND), progression was seriously delayed and led the programme into crisis. This may also affect the initial planned total number of NGPVs to be decreased. However, under the intervention of the Malaysian Government, Boustead Heavy Industries Corporation took over the PSC-ND, thus regaining momentum for the programme. After a long wait of 18 months, the first two hulls, KD Kedah commissioned in June 2006 and KD Pahang commissioned in August 2006. As of July 2009, all six ships had been launched. Subsequently, good progression of the programme has regained interest in the Malaysian decision makers to order the second batch of six NGPVs. Navy Chief Admiral Datuk Abdul Aziz bin Jaafar had recently unveiled that the navy is interested to have the second batch of NGPV ASW configured. The ASW configured NGPV is expected to be able to co-ordinate operations with the Scorpène submarines. The ships will also be upgrade with missiles.[28]

Scorpène-class submarine

Two Scorpène-class submarines were ordered by the RMN on 5 June 2002 under a €1.04 billion (about RM4.78 billion) contract.[7] The two Scorpène submarines were built jointly by the French shipbuilder, Naval Group, and its Spanish partner, Navantia. They are armed with Blackshark wire-guided torpedoes and Exocet SM-39 sub-launched anti-ship missiles.[29][30] The submarine programme also included the redeployment of an Agosta-class submarine retired from the French Navy, for the training of submarine crews. The training of 150 Malaysian sailors, mainly in Brest, France, represented an important aspect of the programme. In 2006, the RMN had launched a nationwide competition to select the names for the first two Malaysian submarines. On 26 July, RMN announced these vessels will be named after historic Malaysians. The first hull will be named KD Tunku Abdul Rahman and the second hull KD Tun Abdul Razak. These vessels are classified as Perdana Menteri class in service with RMN.[3] The first vessel, KD Tunku Abdul Rahman was launched on 24 October 2007 at the Naval Group dockyard, Cherbourg, France.[31]

On 3 September 2009, the first Scorpène submarine of Malaysia KD Tunku Abdul Rahman, arrived at a Port Klang naval base on peninsular Malaysia's west coast after a 54-day voyage from France. Another base is also being constructed on Pulau Langkawi, Kedah to provide the RMN with readier access into the Indian Ocean. Ready access into the Pacific Ocean is available via the existing base at Semporna, Sabah. Defects and problems were found in the submarines such as the inability to submerge and faults in the coolant system of the first submarine, causing delays in the delivery of the second submarine.[32] In October 2012, the Malaysian Navy chief Tan Sri Abdul Aziz Jaafar said that the submarines were in good condition and operational after all the defects repaired by manufacturer.[33]

Utility and anti-submarine helicopter

The Malaysian government is also considering to increase the total of helicopters for the RMN. This includes both utility and anti-submarine helicopter. In September 2020, it is confirmed that Malaysia has sign the contract to purchase three maritime operations helicopter for utility role. The model selected was AgustaWestland AW139.[34] For anti-submarine helicopter, RMN planned to add with either AW-159, Sikorsky MH-60R Seahawk or the Airbus Helicopters H225M. In 2016, an Italian-aerospace defence company, the Finmeccanica has signed a teaming agreement with Malaysian defence vehicle company, the Global Komited to jointly distribute AgustaWestland AW159 helicopters if it was selected by the Malaysian government. Navy chief Admiral Datuk Abdul Aziz Jaafar unveiled an intention of the navy to acquire at least six ASW helicopters as a complement to the soon to be commissioned Maharaja Lela-class frigate.[35][36]

Multi Role Support Ship (MRSS)

RMN has an outstanding requirement for a Multi Role Support Ship (MRSS) to replace KD Sri Inderapura. The MRSS was to be included in the Ninth Malaysian Plan but was postponed due to the financial crisis of 2008.

Maharaja Lela-class Frigate/Littoral Combat Ship (LCS)

Malaysia has launched its program to procure new class of modern frigate. The program is called Second Generation Patrol Vessel. In 2014, Malaysia signed a contract agreement worth MYR9 billion (US$2.8 billion) which was awarded to Boustead Heavy Industries Corporation to build six frigates under the program. The ships will be built based on the Gowind 2500 corvette designed by French shipbuilder Naval Group.

Littoral Mission Ship (LMS)

In 2016, Malaysia and China agreed to jointly develop a littoral mission ship where two ships will be built in China by China Shipbuilding & Offshore International, the rest will be built in Malaysia by local company Boustead Heavy Industries Corporation. A total of 18 ships of this class are planned. The first ship will be delivered by 2019, the second and third by 2020 and the fourth by 2021 for the first batch.

Unmanned aerial vehicle

RMN has set a requirements for the maritime surveillance using unmanned aerial vehicle (UAV). Under Maritime Security Initiatives (MSI) program initiated by United States, Malaysia will receive a total of 18 Boeing Insitu ScanEagle. First six unit delivered to RMN in 2020 and another 12 unit in 2021.[37]

Service Life Extension Program (SLEP)

THALES Naval Division was selected as the contractor of the Service Life Extension Program (SLEP) involving the Kasturi-class corvettes[38] – KD Kasturi, KD Lekir and two Mahamiru (Lerici)-class minehunters – KD Mahamiru, KD Ledang. The corvettes will receive radar and fire control upgrade while the minehunters will receive the new wide band sonar, CAPTAS-2.[39] The program aim to extend the service life of these surface combatants by another 10 years.[40][41] In the future, RMN also planned to give SLEP for other ships in the fleet to lengthening service period of older ships.

15 to 5 program

The RMN took a drastic approach by launching the '15 to 5' Fleet Transformation Program to ensure that the organisation continues as one of the powers in the region. The RMN Future Fleet 15 to 5 programme is aimed at equipping the RMN with Scorpène-class submarines, Maharaja Lela-class frigates, Kedah-class offshore patrol vessels, Keris-class littoral mission ships and Multi Role Support Ship (MRSS).[42]

See also

References

- International Institute for Strategic Studies (15 February 2023). The Military Balance 2023. London: Taylor & Francis. p. 271. ISBN 1000910709.

- "Malaysian Armed Forces". Global Security. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 1 March 2016.

- Shahryar Pasandideh (24 August 2015). "The Royal Malaysian Navy: An Assessment". NATO (The Atlantic Council of Canada). Archived from the original on 3 March 2016. Retrieved 3 March 2016.

- "War Ensign (Malaysia) – Royal Malaysian Navy". CRW Flags. 6 November 2003. Archived from the original on 17 September 2011. Retrieved 2 July 2011.

- "Four Navy vessels handed over to agency". The Star. 27 June 2006. Archived from the original on 11 May 2008. Retrieved 28 June 2006.

- Charles A. Meconis; Michael D. Wallace (2000). East Asian Naval Weapons Acquisitions in the 1990s: Causes, Consequences, and Responses. Greenwood Publishing Group. pp. 82–. ISBN 978-0-275-96251-7.

- "Malaysia buys two new submarines". Utusan Malaysia. 6 June 2002. Archived from the original on 8 March 2016. Retrieved 22 January 2015.

- Faisal Aziz; Dean Yates (1 January 2009). "Malaysian helicopter saves ship from Somali pirates". Reuters. Archived from the original on 10 May 2017. Retrieved 2 January 2009.

- "Malaysia navy foils ship hijack attempt, seizes pirates". BBC News. 22 January 2011. Archived from the original on 23 January 2011. Retrieved 23 January 2011.

- John Garofano; Andrea J. Dew (29 April 2013). Deep Currents and Rising Tides: The Indian Ocean and International Security. Georgetown University Press. pp. 58–. ISBN 978-1-58901-968-3.

- Siti Azielah Wahi (2 September 2013). "7 lanun Somalia dipenjara" (in Malay). Sinar Harian. Archived from the original on 4 January 2014. Retrieved 15 January 2014.

- Alex Richardson (22 January 2011). "Malaysian navy foils hijack attempt off Oman". The Independent. Reuters. Archived from the original on 24 January 2011. Retrieved 23 January 2011.

- "Malaysia navy frees hijacked tanker". Al Jazeera. 22 January 2011. Archived from the original on 6 March 2013. Retrieved 23 January 2011.

- "All On Board MT Orkim Harmony Safe, Pirates Nabbed By Vietnamese Authorities". Bernama. 19 June 2015. Archived from the original on 19 June 2015. Retrieved 19 June 2015.

- Farrah Naz Karim; Tasnim Lokman (22 June 2015). "EXCLUSIVE: 'We passed ship the first time'". New Straits Times. Archived from the original on 22 June 2015. Retrieved 22 June 2015.

- Titus Zheng (1 September 2015). "Indonesian Navy arrests tanker hijacking suspect". IHS Maritime 360. Archived from the original on 2 September 2015. Retrieved 2 September 2015.

- Kronologi pencerobohon Lahad Datu (video) (in Malay). Astro Awani. 15 February 2014. Event occurs at 1:20. Archived from the original on 2 March 2014. Retrieved 27 February 2014.

- "Philippines' Aquino calls for talks on Sabah". Agence France-Presse. Yahoo! News. 17 March 2013. Archived from the original on 19 March 2013. Retrieved 17 March 2013.

- "Heirs of Sultan of Sulu pursue Sabah claim on their own". Philippine Daily Inquirer. 16 February 2013. Archived from the original on 21 February 2013. Retrieved 20 February 2013.

- Michael Ubac; Dona Z. Pazzibugan (3 March 2013). "No surrender, we stay". Philippine Daily Inquirer. Archived from the original on 4 March 2013. Retrieved 3 March 2013.

- Jethro Mullen (15 February 2013). "Filipino group on Borneo claims to represent sultanate, Malaysia says". CNN. Archived from the original on 23 February 2013. Retrieved 25 February 2013.

- Mike Frialde (23 February 2013). "Sultanate of Sulu wants Sabah returned to Phl". The Philippine Star. Archived from the original on 24 February 2013. Retrieved 24 February 2013.

- "Mantan Panglima Tentera Laut" (in Malay). Royal Malaysian Navy. Archived from the original on 26 January 2016. Retrieved 7 February 2016.

- "Pangkat". mafhq.mil.my (in Malay). Malaysian Armed Forces. Archived from the original on 29 April 2020. Retrieved 4 June 2021.

- "RMN other ranks". navy.mil.my. Royal Malaysian Navy. Retrieved 11 July 2021.

- Dzirhan Mahadzir (15 October 2013). "Malaysia to establish marine corps, naval base close to James Shoal". IHS Jane's 360. Archived from the original on 22 October 2013. Retrieved 16 October 2013.

- "KD Panglima Hitam Nama Baru PASKAL TLDM" (in Malay). Royal Malaysian Navy. 18 April 2009. Archived from the original on 8 August 2010. Retrieved 18 April 2009.

- Ridzwan Rahmat (23 April 2015). "Malaysia plans to upgrade four Kedah-class corvettes for ASW role". IHS Jane's 360. Archived from the original on 24 April 2015. Retrieved 23 April 2015.

- "Malaysian sub fires first shot". The Star. 1 November 2014. Archived from the original on 9 January 2015. Retrieved 22 January 2015.

- Zachary Keck (16 July 2013). "The Submarine Race in the Malaccan Strait". The Diplomat. Archived from the original on 8 January 2015. Retrieved 22 January 2015.

- Choi Tuck Wo (24 October 2007). "First Malaysian sub launched". The Star. Archived from the original on 24 October 2007. Retrieved 22 January 2015.

- "Malaysia's Scorpene submarine refuses to submerge". Defense World. 16 February 2010. Archived from the original on 23 July 2011. Retrieved 22 January 2015.

- Sandra Sokial (16 October 2012). "Submarines are not defective – Navy chief". The Borneo Post. Archived from the original on 2 November 2014. Retrieved 22 January 2015.

- "Fifth Time Lucky". malaysiandefence.com.

- Siva Govindasamy (25 April 2008). "Malaysian navy to seek funding for ASW helicopters". Flightglobal. Archived from the original on 25 March 2015. Retrieved 22 January 2015.

- Carl Thayer (23 January 2015). "The Philippines, Malaysia, and Vietnam Race to South China Sea Defense Modernization". The Diplomat. Archived from the original on 24 January 2015. Retrieved 23 January 2015.

- Parameswaran, Prashanth. "Drone Delivery Puts the Focus on US-Malaysia Security Cooperation". thediplomat.com. The Diplomat. Retrieved 1 April 2020.

- "Kasturi Class Corvettes, Malaysia". naval-technology.com. Archived from the original on 24 December 2014. Retrieved 3 March 2016.

- "Thales On Board the Littoral Combat Ships of the Royal Malaysian Navy". Thales Group. 18 February 2014. Archived from the original on 3 March 2016. Retrieved 3 March 2016.

- "2006年国防部年度报告书之一:马来西亚采购6套FN-6 第2批护卫舰成本介于35亿令吉至50亿令吉" (in Chinese). KL Security Review. 2006. Archived from the original on 22 October 2013. Retrieved 22 January 2015.

- "Malaysia Buying European on Air, Anti-Air, and Naval Fronts". Defense Industry Daily. 9 December 2005. Archived from the original on 25 February 2016. Retrieved 22 January 2015.

- "Industries – Export markets (Defence, Aerospace and Maritime to Malaysia)". Austrade. 13 March 2014. Archived from the original on 3 March 2016. Retrieved 22 January 2015.

Further reading

- James Goldrick, Jack McCaffrie, Navies of South-East Asia: A Comparative Study (London: Routledge, 2012 ISBN 9780415809429)

_in_the_South_China_Sea_during_landing_qualifications_June_18%252C_2013%252C_as_part_130618-N-PD773-083.jpg.webp)

.svg.png.webp)