Tadeusz Mazowiecki

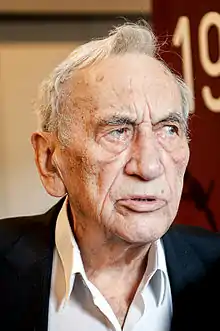

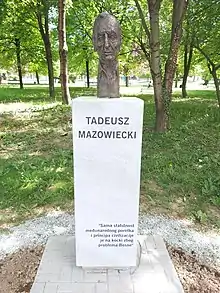

Tadeusz Mazowiecki (IPA: [taˈdɛ.uʂ mazɔˈvjɛtskʲi] ⓘ; 18 April 1927 – 28 October 2013) was a Polish author, journalist, philanthropist and Christian-democratic politician, formerly one of the leaders of the Solidarity movement, and the first non-communist Polish prime minister since 1946.[1]

Tadeusz Mazowiecki | |

|---|---|

| |

| Prime Minister of Poland | |

| In office 24 August 1989 – 12 January 1991 | |

| President | Wojciech Jaruzelski Lech Wałęsa |

| Deputy | Leszek Balcerowicz Czesław Janicki Jan Janowski Czesław Kiszczak |

| Preceded by | Edward Szczepanik (Exile) Czesław Kiszczak |

| Succeeded by | Jan Krzysztof Bielecki |

| Chairman of the Freedom Union | |

| In office 23 April 1994 – 1 April 1995 | |

| Preceded by | Himself (As Chairman of the Democratic Union) |

| Succeeded by | Leszek Balcerowicz |

| Chairman of the Democratic Union | |

| In office 20 May 1991 – 24 April 1994 | |

| Preceded by | Position established |

| Succeeded by | Himself (As Chairman of the Freedom Union) |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 18 April 1927 Płock, Poland |

| Died | 28 October 2013 (aged 86) Warsaw, Poland |

| Political party | PAX Association (1949–55) Znak (1961–72) Solidarity (1980–91) Democratic Union (1991–94) Freedom Union (1994–2005) Democratic Party (2005–06) |

| Spouse(s) | Krystyna (d.) Ewa (d.) |

| Children | Wojciech Adam Michal |

| Profession | Author, journalist, social worker |

| Awards | |

| Signature | |

Biography

Tadeusz Mazowiecki was born in Płock, Poland on 18 April 1927 to a Polish noble family, which uses the Dołęga coat of arms.[2][3] Both his parents worked at the local Holy Trinity Hospital: his father was a doctor there while his mother ran a charity for the poor.[4] His education was interrupted by the outbreak of World War II. During the war he worked as a runner in the hospital his parents worked for.[4] After the German forces had been expelled from Płock, Tadeusz Mazowiecki resumed his education and in 1946, he graduated from "Marshal Stanisław Małachowski" Lyceum, the oldest high school in Poland and one of the oldest continuously operating school in Europe.[4] He then moved to Łódź and then to Warsaw, where he joined the Law Faculty of the Warsaw University. However, he never graduated and instead devoted himself to activity in various Catholic associations, journals and publishing houses.[5]

PAX and WTK

Already during his brief stay at the Warsaw University Mazowiecki joined the Caritas Academica charity organisation, he also briefly headed the University Printing Cooperative between 1947 and 1948.[5] In 1946 he also joined Karol Popiel's Labour Party. However, later that year the party was outlawed by the new Stalinist authorities of Soviet-controlled Poland. Almost all other non-communist organisations soon also became a target of state-sponsored repressions.

One of the exceptions was the PAX Association, the only large Catholic organisation supported by the Communist authorities – and supporting the authorities in their conflict with the Catholic clergy.[6] Mazowiecki joined PAX in 1948, initially as one of the leaders of the youth circles. He openly criticised Bolesław Piasecki's vision of the association and his allegiance to the Communists.[6] He nevertheless rose through the ranks of various journals published by the association. Initially, a journalist in the Dziś i Jutro weekly, in 1950 he became the deputy editor-in-chief of Słowo Powszechne daily newspaper. In 1952 the conflict between Piasecki and the opposition within the PAX (the so-called Fronda, composed mostly of young intellectuals) led to Mazowiecki being expelled from the daily and relegated to a less prominent role of an editor of newly created Wrocławski Tygodnik Katolików (Wrocław Catholic Weekly, WTK).[7] Until 1955 he served as the editor-in-chief of that journal, he also remained one of the leaders of the opposition within the association, criticising Piasecki and his associates for their conflicts with the Catholic hierarchy, loyalty to the communist authorities, and lack of democratic procedures within PAX.[8] For that he was eventually dismissed from the WTK and eventually in 1955 expelled from the association altogether.[9]

Involvement in Communist propaganda

Despite criticizing Piasecki, Mazowiecki offered his own support to the Communist authorities, expressed in press articles and other publications. In 1952, he published a pamphlet titled The enemy remains the same (Wróg pozostał ten sam, co-authored with Zygmunt Przetakiewicz, then editor-in-chief of WTK) imputing an alliance between Polish anti-communist resistance movement and Nazi war criminals.[10] In a press article published in WTK in 1953, Mazowiecki fiercely condemned Czesław Kaczmarek, then Bishop of Kielce. Kaczmarek, groundlessly accused by the Communists of being an American and Vatican spy, was later sentenced to 12 years in prison.

Club of Catholic Intelligence and 'Więź'

Having left PAX, together with a group of his former colleagues Tadeusz Mazowiecki started cooperation with the Tygodnik Powszechny weekly, Po prostu journal and the Crooked Circle Club.[11] While these journals were formally dependent on PAX, they were increasingly liberal and independent. Eventually, during the Polish October of 1956 Tadeusz Mazowiecki became one of the founders of the All-Polish Club of Progressive Catholic Intelligentsia, the predecessor of Club of Catholic Intelligentsia (KIK), the first all-national Catholic organisation independent of the Communist authorities in post-war Poland.[12] Until 1963 he served as a board member of KIK.[13] He was also a founding member of the Więź Catholic monthly in 1958 and served as its first editor-in-chief.[14][15] While relatively independent from the Communist authorities, the monthly was also independent from the Catholic hierarchy, which often led to conflicts with both.[16][17] In his texts published in Więź Mazowiecki, inspired by Emmanuel Mounier's personalist ideas, sought intellectual dialogue with members of left-leaning lay intelligentsia.[18][19]

Mazowiecki was a friend and confidant of Pope John Paul II.

Politician and dissident

One of the lasting effects of Władysław Gomułka's rise to power during the Polish October 1956 was the dissolution of PAX. A group of former PAX dissenters, the "Fronda", along with some of the professors of the Catholic University of Lublin approached Gomułka in 1956. In exchange for their support, Gomułka accepted the creation of Znak Association along with its publishing house, the only such venture independent from the communist government in contemporary Poland. Moreover, a small group of 12 Catholics associated with the Znak were allowed to run in the Polish legislative election of 1957, among them Tadeusz Mazowiecki. While the 12 members of parliament elected that year were formally independent, they formed the first form of opposition to the rule of the Polish United Workers' Party within the Polish Sejm, dubbed the "MP circle of Znak" (Polish: koło poselskie Znak). Mazowiecki remained a member of the Sejm until 1971, serving his second, third and fourth terms as a member of the Catholic "party".[20]

During his parliamentary career, he was an active member of the Commission on Education and the Commission on Work and Social Matters.[21] As Poland was effectively a one-party state, the role of the token opposition was mostly symbolic. However, some of Mazowiecki's speeches and interpellations made a large impact on Polish society. Such was the case of his critique of the official curriculum of Polish schools underlining the crucial role of Karl Marx's historical materialism,[22] or his isolated protest against the new Assemblies Act, effectively putting an end even to a theoretical freedom of assembly in Poland.[23] In 1968 he was the only member of parliament to raise the issue of the brutal suppression of the students' demonstrations during the 1968 Polish political crisis.[24] In the aftermath of the bloody quelling of the 1970 protests, in which 42 people were killed by the army and the Citizens' Militia, Tadeusz Mazowiecki unsuccessfully demanded that the matter be investigated in order to find those responsible for the bloodshed.[1][25] This and similar acts of questioning the actions of the Communist authorities made Mazowiecki one of the unwanted members of parliament and consequently in 1972 the party did not allow him to run for his fifth term.[26]

Having left the Sejm, Mazowiecki became the head of Warsaw chapter of the Club of Catholic Intelligentsia and one of the best-known Polish dissidents. In early 1976, soon after the publication of the Letter of 59, Mazowiecki initiated a similar letter to the PUWP signed by most members of the former Znak circle.[27] Although not a member of the Workers' Defence Committee, he supported it on numerous occasions, notably in the aftermath of the June 1976 protests in Radom and Ursus.[28][29] An heir to a long tradition of organic work, on 22 January 1978 Tadeusz Mazowiecki, together with other Polish dissidents, including Stefan Amsterdamski, Andrzej Celiński and Andrzej Kijowski, became one of the founding members of the Society of Scientific Courses, the predecessor of the Flying University.[30]

Solidarity and the fall of Communism

In August 1980, he headed the Board of Experts, which supported the workers from Gdańsk who were negotiating with the authorities.[1] From 1981, he was the editor-in-chief of the Tygodnik Solidarność weekly magazine.[31] After martial law was declared in December 1981 he was arrested and imprisoned in Strzebielnik, then in Jaworz and finally in Darłówek.

He was one of the last prisoners to be released on 23 December 1982.[1] In 1987, he spent a year abroad, during which he talked to politicians and trade union representatives. Starting in 1988, he held talks in Magdalenka. He firmly believed in the process of taking power from the ruling Polish United Workers' Party through negotiation and thus he played an active role in the Polish Round Table Talks, becoming one of the most important architects of the agreement by which partially free elections were held on 4 June 1989. While the Communists and their satellites were guaranteed a majority in the legislature, Solidarity won all of the contested seats in a historic landslide.[1]

The Communists had originally planned for Solidarity to be a junior partner in the ensuing government. However, Solidarity turned the tables on the Communists by persuading the Communists' two satellite parties to switch their support to Solidarity. This would all but force Communist President Wojciech Jaruzelski to appoint a Solidarity member as prime minister, heading the first government in 45 years that was not dominated by Communists. At a meeting on 17 August 1989, Jaruzelski finally agreed to Lech Wałęsa's demand to pick a Solidarity member as the next prime minister. Walesa chose Mazowiecki as a Solidarity candidate to lead the coming administration. On 21 August 1989 General Jaruzelski formally appointed Mazowiecki as Prime Minister-designate. On 24 August 1989, he won a vote of confidence in the Sejm. He thus became the first Polish prime minister in 43 years who was not either a Communist or a fellow traveler, as well as the first non-communist Prime Minister of an Eastern European country in over 40 years.[32]

Prime Minister

On 13 September 1989 during his long investiture speech outlining the extensive political agenda of his nominated cabinet prior to the mandatory confidence vote, Mazowiecki grew weak necessitating a one-hour break in proceedings. However, the government was approved by a vote 402–0, with 13 abstentions. Mazowiecki's government managed to carry out many fundamental reforms in a short period. The political system was thoroughly changed; a full range of civil freedoms as well as a multi-party system were introduced and the country's emblem and name were changed (from the People's Republic of Poland to the Republic of Poland). On 29 December 1989, the fundamental changes in the Polish Constitution were made. By virtue of these changes, the preamble was deleted, the chapters concerning political and economic forms of government were changed, the chapters concerning trade unions were rewritten and a uniform notion of possession was introduced.[33]

Mazowiecki used enormous popularity and credibility of the Solidarity movement to transform the Polish economy by a set of deep political and economic reforms.[34] Better known under the name of Balcerowicz Plan after Mazowiecki's minister of finance, Leszek Balcerowicz, the reforms enabled the transformation of the Polish economy from a centrally-planned economy to a market economy.[34] The reforms have prepared the ground for measures stopping the hyperinflation, introducing free-market mechanisms and privatisation of state-owned companies, houses and land. The plan resulted in reduced inflation and budget deficit, while simultaneously increasing Unemployment and worsening the financial situation of the poorest members of society. In 1989, in his first parliamentary speech in Sejm, Mazowiecki talked about a "thick line" (gruba linia): "We draw a thick line on what has happened in the past. We will answer for only what we have done to help Poland to rescue her from this crisis from now on". Originally, as Mazowiecki explains, it meant non-liability of his government for damages done to the national economy by previous governments.[35]

Later years

In 1991 Mazowiecki was appointed the United Nations' Special Rapporteur on the Situation of Human Rights in the Territory of the Former Yugoslavia. In 1993 he issued a report on human rights violations in the Former Yugoslavia but two years later Mazowiecki stepped down in protest at what he regarded as the international community's insufficient response to atrocities committed during the Bosnian war, particularly the Srebrenica massacre committed by the Serb army that year.[36]

A conflict with Lech Wałęsa resulted in the disintegration of Citizens' Parliamentary Club that represented Solidarity camp. The Citizens' Parliamentary Club was divided into Centre Agreement, which supported Wałęsa, and ROAD, which took sides with Mazowiecki. That conflict lead both politicians to compete in presidential election at the end of 1990. Mazowiecki, who during Solidarity times was an advisor to Lech Wałęsa and strike committee in Gdańsk's shipyard, stood against Wałęsa in the election and lost to him. He did not even join the second round (he gained the support of 18.08% of people – 2,973,364 votes) and was defeated by Stanisław Tymiński, a maverick candidate from Canada.

In 1991, Mazowiecki became a chairman of the Democratic Union (later Freedom Union), and from 1995 he was its honorary president. Together with Jan Maria Rokita, Aleksander Hall and Hanna Suchocka he represented the Christian Democratic wing of the party. Between 1989 and 2001 Mazowiecki was a representative to the Polish Parliament (first from Poznań, later from Kraków).

Mazowiecki was a member of parliament in the first, second, and third term (a member of the Democratic Union), later the Freedom Union. During the National Assembly (1997) he introduced compromise preamble of Polish constitution (previously written by founders of Tygodnik Powszechny weekly), which was accepted by the National Assembly. In November 2002, he left the Freedom Union, in the protest against abandoning Christian Democrat International, as well as his party's electoral and local coalition with the Democratic Left Alliance and Self-Defence Party in Warmian-Masurian Voivodeship.

In 2005, he became one of the founders of the Democratic Party – demokraci.pl – created through expanding the former Freedom Union by new members, especially young people, and few left-wing politicians. He was a leader on the parliamentary list in parliamentary elections in Warsaw constituency in 2005 with 30143 votes. The highest number of votes he gained in Żoliborz district, and the lowest in Rembertów. Until 2006 he was the leader of its Political Council.

Mazowiecki received numerous awards including an honorary degree from the universities in: Leuven, Genoa, Giessen, Poitiers, Exeter, Warsaw and the Katowice University of Economics. He also received the Order of White Eagle (1995), Golden Order of Bosnia (1996), Légion d'honneur (1997), Srebrnica Award (2005), the Giant award (1995) awarded by Gazeta Wyborcza (Election Gazette) in Poznań and Jan Nowak-Jezioranski Award (2004). In 2003, he was elected to the board of directors of the International Criminal Court's Trust Fund for Victims.[37] Mazowiecki was a member of the Club of Madrid.[38] He was a supporter of a more united Europe.[39]

Mazowiecki died in Warsaw on 28 October 2013,[40] having been taken to hospital the previous week with a fever.[41] Foreign Minister Radosław Sikorski stated that he was "one of the fathers of Polish liberty and independence".[1] He was survived by three sons from his second marriage.[41]

References

Citations

- BBC (corporate author), p. 1

- Kopka & Żelichowski, p. 135

- Pszczółkowski, pp. 1-2

- Pac, p. 1

- Friszke, "Koło posłów Znak...", p. 606

- Dudek, p. 181

- Dudek, p. 218

- Dudek, p. 219

- Dudek, pp. 219 & 222

- Jak Mazowiecki zwalczał podziemie, "Historia Do Rzeczy", issue No. 1/2013 Archived 1 March 2013 at the Wayback Machine

- Friszke, "Opozycja polityczna...", p. 186

- Friszke, "Oaza na Kopernika...", p. 39

- Friszke, "Oaza na Kopernika...", pp. 297-298

- Friszke, "Oaza na Kopernika...", p. 51

- Szporer, p. 259

- Friszke, "Oaza na Kopernika...", p. 89

- Friszke, "Koło posłów Znak...", p. 100

- Friszke, "Oaza na Kopernika...", p. 70

- Friszke, "Oaza na Kopernika...", p. 86

- Ost, p. 219

- Friszke, "Koło posłów...", p. 44

- Friszke, "Koło posłów...", pp. 46-47

- Friszke, "Koło posłów...", p. 50

- Friszke, "Koło posłów...", p. 83

- Friszke, "Oaza na Kopernika...", p. 116

- Friszke, "Oaza na Kopernika...", pp. 128-129

- Friszke, "Oaza na Kopernika...", pp. 157-159

- Friszke, "Oaza na Kopernika...", p. 179

- Friszke, "Opozycja polityczna...", p. 398

- Friszke, "Opozycja polityczna...", pp. 501-502

- Tagliabue, "Solidarity seems on verge...", p. 1

- Baczyńska & Słowikowska, p. 1

- Tagliabue, "Poles Approve Solidarity-Led Cabinet", p. 1

- Sachs, pp. 44-46

- Leszkowicz, p. 1

- WŻ, p. 22

- Amnesty International (corporate author), p. 1

- Club de Madrid (corporate author), p. 1

- Dzieduszycka, p. 1

- Kospa et al., p. 1

- Ścisłowska, p. 1

Bibliography

- Amnesty International (corporate author) (12 September 2003). "Amnesty International welcomes the election of a Board of Directors". Amnesty International. Archived from the original on 19 November 2006. Retrieved 1 August 2007.

{{cite web}}:|author=has generic name (help) - Baczyńska, Gabriela; Słowikowska, Karolina (28 October 2013). Alistair Lyon (ed.). "Poland's Tadeusz Mazowiecki, first PM after communism, dies". Reuters. Retrieved 28 October 2013.

- BBC (corporate author) (28 October 2013). "Poland's former PM Tadeusz Mazowiecki dies aged 86". BBC News Europe. London: BBC. Retrieved 30 October 2013.

{{cite news}}:|author=has generic name (help) - Club de Madrid (corporate author) (2010). "Mazowiecki, Tadeusz; Prime Minister of Poland (1989-1990)". clubmadrid.org. Club de Madrid. Archived from the original on 2 November 2013. Retrieved 30 October 2013.

{{cite web}}:|author=has generic name (help) - Dudek, Antoni (1990). Bolesław Piasecki: próba biografii politycznej [Bolesław Piasecki: sketch of a political biography]. ISBN 0-906601-74-6.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help)CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Mazowiecki, Tadeusz (1997). "Interview with Tadeusz Mazowiecki". EuroDialog (Interview). No. 0/97. Interviewed by Małgorzata Dzieduszycka. Retrieved 9 January 2012.

- Friszke, Andrzej (1994). Opozycja polityczna w PRL 1945-1980 [Political opposition in the PRP, 1945-1980] (in Polish). London: Aneks. ISBN 1897962037.

- Friszke, Andrzej (1997). Oaza na Kopernika: Klub Inteligencji Katolickiej, 1956-1989 [Oasis at Kopernika Str.: Club of Catholic Intelligentsia, 1956-1989]. Biblioteka "Więzi" (in Polish). Vol. 100. Warszawa: Biblioteka "Więzi". ISBN 83-85124-90-X. ISSN 0519-9336.

- Friszke, Andrzej (2002). Koło posłów "Znak" w Sejmie PRL 1957-1976 ["Znak" parliamentary club in the Sejm of the PRP; 1957-1976] (in Polish). Warsaw: Wydawnictwo Sejmowe. ISBN 83-7059-527-8.

- Kopka, Bogusław; Żelichowski, Ryszard (1997). Rodem z Solidarnośći: sylwetki twórców NSZZ "Solidarność" [Roots in Solidarity: silhouettes of the creators of "Solidarity"] (in Polish). Stowarzyszenie Archiwum Solidarności. p. 135. ISBN 9788370540999.

- kospa; dan; gaw (October 2013). "Tadeusz Mazowiecki nie żyje. Miał 86 lat. "Uczył nas pokory w polityce"" [Tadeusz Mazowiecki dead. He was 86. "He taught us humility in politics"]. Gazeta Wyborcza (in Polish) (28 October 2013). ISSN 0860-908X. Retrieved 28 October 2013.

- Leszkowicz, Dagmara (28 October 2013). "Poland's first post-communist PM Mazowiecki dead at 86". Reuters. Retrieved 29 October 2013.

- Musiał, Filip (3 December 2007). "Katolicy przeciwko kościołowi" [Catholics against the Church]. Rzeczpospolita (in Polish). Archived from the original on 8 September 2012. Retrieved 30 October 2013.

- Ost, David (1990). Solidarity and the Politics of Anti-Politics: Opposition and Reform in Poland Since 1968. Temple University Press. p. 219. ISBN 9780877226550.

- J. Pac (October 2013). "Rodzinne miasto Mazowieckiego w żałobie" [Mazowiecki's native town in mourning]. Rzeczpospolita (in Polish) (28 October 2013). Archived from the original on 2 November 2013. Retrieved 31 October 2013.

- Pszczółkowski, Adam A. (2 November 2013). "Informacja prasowa na temat rodziny Tadeusza Mazowieckiego" [Press release: on the family of Tadeusz Mazowiecki] (PDF). szlachta.org.pl (in Polish). Związek Szlachty Polskiej. Retrieved 7 November 2013.

- Sachs, Jeffrey (1993). Poland's jump to the market economy. Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press. ISBN 0-262-69174-4.

- Szporer, Michael (2012). Solidarity: The Great Workers Strike of 1980. Lexington Books. p. 259. ISBN 9780739174876.

- Ścisłowska, Monika (October 2013). "Tadeusz Mazowiecki, Polish prime minister, dies at 86". The Washington Post. ISSN 0190-8286.

- Tagliabue, John (18 August 1989). "Solidarity seems on verge of forming Polish cabinet". The New York Times. Retrieved 14 July 2013.

- Tagliabue, John (13 September 1989). "Poles Approve Solidarity-Led Cabinet". The New York Times. Retrieved 29 October 2013.

- W.Ż. (5 March 2008). "Poland Recognizes Kosovo". The Warsaw Voice (5 March 2008): 22. ISSN 0860-7591. Archived from the original on 12 April 2010. Retrieved 30 October 2013.