Taiwanese Australians

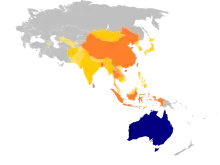

Taiwanese Australians are Australian citizens or permanent residents who carry full or partial ancestry from the East Asian island country of Taiwan or from preceding Taiwanese regimes.

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| 46,822 (Taiwanese-born at 2016 census)[1] 55,960 (according to Taiwan govt. data)[2] | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| Sydney, Brisbane, Melbourne, Perth, Adelaide | |

| Languages | |

| Australian English · Taiwanese Mandarin · Taiwanese Hokkien · Taiwanese Hakka · Varieties of Chinese · Formosan languages | |

| Religion | |

| Buddhism · Christianity · Chinese folk religion · Irreligion · Taoism · Other | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Chinese Australians, Hong Kong Australians, Indonesian Australians, Japanese Australians, Taiwanese indigenous peoples |

Taiwanese people can be divided into two main ethnic groups; the Han Taiwanese, who have Han Chinese ancestry and constitute over 95% of the population, and the Taiwanese indigenous peoples, who have Austronesian ancestry and constitute approximately 2% of the population.[3] The Han Taiwanese majority can be loosely subdivided into the Hoklo (70%), Hakka (14%) and "Mainlanders (Waishengren)" (post-1949 Chinese immigrants) (14%).[4] Historically, the first known Taiwanese people in Australia arrived from the Netherlands East Indies (NEI) (historical Indonesia) during World War II (1939–1945), having been brought to the country by the exiled NEI government as civilian internees in 1942;[5] at the time, Taiwan was part of the Empire of Japan and Taiwanese people were considered Japanese. Subsequently, Taiwanese mass immigration to Australia began during the 1970s as a result of the complete dismantlement of the White Australia Policy (1901–1973), which historically prevented Taiwanese people and other non-Europeans from permanently settling in the country.

History

Early history

Prior to 1942, it is unknown whether there were any Taiwanese people living in Australia.

Internment of Japanese and Taiwanese people in Australia during WWII

Historically, Taiwanese Australians have had a significant presence in Tatura and Rushworth, two neighbouring countryside towns respectively located in the regions of Greater Shepparton and Campaspe (Victoria), in the fertile Goulburn Valley.[6] During World War II, ethnic-Japanese (from Australia, Southeast Asia and the Pacific) and ethnic-Taiwanese (from the Netherlands East Indies) were interned nearby to these towns as a result of anti-espionage/collaboration policies enforced by the Australian government (and WWII Allies in the Asia-Pacific region).[7] Roughly 600 Taiwanese civilians (entire families, including mothers, children and the elderly) were held at "Internment Camp No. 4", located in Rushworth but nominally labeled as being part of the "Tatura Internment Group", between January 1942 and March 1946.[8] Most of the Japanese and Taiwanese civilians were innocent and had been arrested for racist reasons (see the related article "Internment of Japanese Americans", an article detailing similar internment in America).[9] Several Japanese and Taiwanese people were born in the internment camp and received British (Australian) birth certificates from a nearby hospital. Several Japanese people who were born in the internment camp were named "Tatura" in honour of their families' wartime internment at Tatura. During wartime internment, many working age adults in the internment camp operated small businesses (including a sewing factory) and local schools within the internment camp.[8] Regarding languages, schools mainly taught English, Japanese, Mandarin and Taiwanese languages (Hokkien, Hakka, Formosan). Filipinos are purported to have also been held at the camp, alongside Koreans, Manchus (possibly from Manchukuo), New Caledonians, New Hebrideans, people from the South Seas Mandate, people from Western New Guinea (and presumably also Papua New Guinea) and Aboriginal Australians (who were mixed-Japanese).[10][11]

After the war, internees were resettled in their country of ethnic origin, rather than their country of nationality or residence, with the exception of Japanese Australians, who were generally allowed to remain in Australia. Non-Australian Japanese, who originated from Southeast Asia and the Pacific, were repatriated to Occupied Japan. On the other hand, Taiwanese, most of whom originated from the Netherlands East Indies, were repatriated to Occupied Taiwan. The repatriation of Taiwanese during March 1946 caused public outcry in Australia due to the allegedly poor living conditions aboard the repatriating ship "Yoizuki", in what became known as the "Yoizuki Hellship scandal". Post-WWII, the Australian government was eager to expel any Japanese internees who did not possess Australian citizenship, and this included the majority of Taiwanese internees as well. However, the Republic of China (ROC) was an ally of Australia, and since the ROC had occupied Taiwan during October 1945, many among the Australian public believed that the Taiwanese internees should be deemed citizens of the ROC, and, therefore, friends of Australia, not to be expelled from the country, or at least not in such allegedly appalling conditions. This debate concerning the citizenship of Taiwanese internees—whether they were Chinese or Japanese—further inflamed public outrage at their allegedly appalling treatment by the Australian government. Additionally, it was technically true that several "camp babies"—internees who had been born on Australian soil whilst their parents were interned—possessed Australian birth certificates, which made them legally British subjects. However, many of these camp babies were also deported from the country alongside their non-citizen parents. There was also a minor controversy regarding the destination of repatriation, with some of the less Japan-friendly Taiwanese fearing that they would be repatriated to Japan, though this was resolved when they learnt that they were being repatriated to Taiwan instead.

On January 5, 1993, a plaque was erected at the site of the internment camp at Tatura (Rushworth) to commemorate the memory of wartime internment. Forty-six Japanese and Taiwanese ex-internees, as well as a former (Australian) camp guard, are listed on the plaque.[12]

History from the 1970s and onward

Starting from 1976, Australia began to consider the Taiwanese to be nationals of the ROC (Taiwan), making a distinction between them and the mainland Chinese living in the PRC, but considering both people groups to be ethnic-Chinese.[13] The White Australia Policy had been completely abolished by 1973, and so Taiwanese (and mainland Chinese) immigration to Australia had been gradually increasing since then.[14] The Australian Government specifically targeted Taiwanese nationals for immigration during the 1980s. Simultaneously, there was an influx of mainland Chinese immigration to Australia during the 1980s due to the PRC relaxing its immigration policies. The majority of Taiwanese immigrants to Australia during the 1970s and onward were highly-skilled white-collar workers.[15]

The current total population of Taiwanese Australians is unknown, with only 1st-generation and 2nd-generation Taiwanese being counted in the Australian Census as Taiwanese, and with 3rd-generation Taiwanese or older families being counted as just "Australian". The current number of 1st/2nd-generation Taiwanese Australians is roughly 45,000–55,000 people. It is estimated that roughly 95%–90% of Taiwanese Australians are 1st/2nd-generation Australians.[16]

Culture

Language

In Australia, Australian English is the de facto national language and most immigrants to Australia are expected to be proficient in the language. Unlike in the United States, for example, there aren't many large non-Anglophone ethnic enclaves in Australia, since Australian history has been heavily dominated by British colonialism. Multiculturalism in Australia is a fairly recent phenomenon that was intentionally encouraged by successive Australian governments as part of the country's rapidly changing foreign policy and ethnic policy following the conclusion of World War II (1939–1945).

Taiwanese immigrants to Australia can usually speak their native Taiwanese languages, including Taiwanese Mandarin, Taiwanese Hokkien, Taiwanese Hakka, and various other Taiwanese languages (such as the Taiwanese indigenous languages). However, proficiency in these languages typically already drops by the second generation, i.e. the first generation born in Australia. Depending on which social class and/or ethnic group the Taiwanese immigrant parents originate from, their children may only remain proficient in one of these languages. Typically, proficiency in Mandarin is usually retained by the second generation, whereas proficiency in Hokkien and Hakka drops significantly unless the parents place a particular emphasis on retaining proficiency in these languages. Internationally and in Australia, Mandarin is far more useful for travelling and business than other Taiwanese languages, which may result in parents prioritising Mandarin. By the third and fourth generations, proficiency in even Mandarin is usually lost entirely, unless the family has been residing in a Chinese or Taiwanese ethnic enclave in Australia for several decades. Such enclaves do exist, and they are usually known as "Chinatowns". Chinese enclaves in Australia are quite large and numerous but Taiwanese enclaves aren't.

According to the 2016 Australian census, approximately 90% of Taiwanese immigrants to Australia, including those who have come to Australia during preceding decades, speak Mandarin as their primary non-English language at home, whereas approximately 2% speak Hokkien. Approximately 66% of those who speak a language other than English at home also speak English (i.e. they speak multiple languages). Approximately 5% speak only or primarily English at home.[13]

Settlement

The Taiwanese community in Australia is relatively minor and is often not distinguished from the Chinese community in Australia. Brisbane (QLD) hosts the largest Taiwanese community in Australia. Sydney (NSW) and Melbourne (VIC) also host significant Taiwanese communities. Typically, Taiwanese people immigrating to Australia prefer to settle in major cities.

See also

- Articles relating to Australian people:

- Articles relating to Taiwanese Australians:

References

- "2016 Census Community Profiles: Australia". Quickstats.censusdata.abs.gov.au. Retrieved 18 December 2018.

- "International Migration Database". Archived from the original on 11 June 2009. Retrieved 7 October 2019.

- "People". Government Portal of the Republic of China (Taiwan). Retrieved 25 June 2020.

While Taiwan may be described as a predominantly Han Chinese society, with more than 95 percent of the population claiming Han ancestry, its heritage is actually much more complex... There is growing appreciation in Taiwan for the cultural legacies of the 16 officially recognized Austronesian-speaking tribes, which constitute a little more than 2 percent of the population.

- "Ethnic Groups Of Taiwan". WorldAtlas. Retrieved 25 June 2020.

Taiwan has many ethnic groups with the largest group being the Hoklo Han Chinese with about 70% of the total population followed by the Hakka Han Chinese who make up about 14% of the total population...The mainland Chinese are a group of people who migrated to Taiwan in the 1940s from mainland China after Kuomintang lost the Chinese civil war in 1949... The mainlanders make up 14% of the population due to immigration.

- Piper, Christine (14 August 2014). "Japanese internment a dark chapter of Australian history". The Sydney Morning Herald. Retrieved 25 June 2020.

While numerous books, films and photographs have explored the internment of Japanese civilians in the United States and Canada, the situation in Australia has had limited coverage... Of the 4301 Japanese civilians interned in Australia, only a quarter had been living in Australia when hostilities began, with many employed in the pearl diving industry... The remaining three-quarters had been arrested in Allied-controlled countries such as the Dutch East Indies... They included ethnic Formosans (Taiwanese) and Koreans.

- "Tatura Irrigation and Wartime Camps Museum". Visit Shepparton.

- "Prisoner of War and Internment Camps; World War II Camps". Tatura Museum.

- "Tatura – Rushworth, Victoria (1940–47)". National Archives of Australia. Retrieved 7 June 2019.

- Blakkarly, Jarni (25 April 2017). "Japanese survivors recall Australia's WWII civilian internment camps". SBS News. Retrieved 7 June 2019.

- Nagata, Yuriko (13 September 1993). "Japanese internment in Australia during World War II". The University of Adelaide (This is a website link to a PDF version of an Australian thesis paper on Japanese internment in Australia during WWII.).

- Blakkarly, Jarni (24 April 2017). "The Japanese and the dark legacy of Australia's camps". SBS News. Retrieved 7 June 2019.

- Piper, Christine (6 March 2012). "Tatura family internment camp". Loveday Project.

- "Taiwanese Culture – Taiwanese in Australia". Cultural Atlas. Retrieved 6 April 2019.

- "Fact sheet – Abolition of the 'White Australia' Policy". archive.homeaffairs.gov.au. Retrieved 6 April 2019.

- Ma, Laurence J. C.; Cartier, Carolyn L. (2003). The Chinese Diaspora: Space, Place, Mobility, and Identity. Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 9780742517561.

- "Origins: History of immigration from Taiwan – Immigration Museum, Melbourne Australia". museumsvictoria.com.au. Retrieved 27 December 2018.