Tanforan Assembly Center

The Tanforan Assembly Center was created to temporarily detain nearly 8,000 Japanese Americans, mostly from the San Francisco Bay Area, under the auspices of Executive Order 9066. After the order was signed in February 1942, the Wartime Civil Control Administration acquired Tanforan Racetrack on April 4 for use as a temporary assembly center; plans called for the site to be used to accommodate up to 10,000 "evacuees" while permanent relocation sites were being prepared further inland.[1] The Tanforan Assembly Center began operation in late April 1942, the first stop for thousands who were forced to relocate and undergo internment during World War II. The majority were U.S. citizens of Japanese ancestry who were born in the United States. Tanforan Assembly Center was operated for slightly less than six months; most detainees at Tanforan were transferred to the Topaz War Relocation Center in Utah, starting in September. The transfer to Topaz was completed by mid-October, and the site was turned over to the Army a few weeks later.

Tanforan Assembly Center | |

|---|---|

Internment camp for Japanese-Americans, mostly from the San Francisco Bay Area | |

.png.webp) Aerial view of the Tanforan Assembly Center, taken sometime in 1942. | |

| Etymology: named for the racetrack | |

| Coordinates: 37°38′08″N 122°25′09″W | |

| Country | United States |

| State | California |

| City | San Bruno |

| First internees arrived | April 28, 1942 |

| Last internees left | October 13, 1942 |

| Area | |

| • Total | 118 acres (48 ha) |

| Population | |

| • Total | 7,816 (max) |

| Designated | May 13, 1980 |

| Reference no. | 934.09 |

Statistics and administration

The people detained at Tanforan had previously lived in the San Francisco Bay Area, in the counties of San Francisco, Alameda, Contra Costa, and San Mateo; a small group was taken from San Joaquin County.[2] Internees began arriving on April 28. The maximum population at Tanforan was 7,816 on July 25, 1942; Tanforan was the second-largest assembly center by population, but still held less than half the population at Santa Anita Assembly Center. The last detainees left the site on October 13.[3]: 227 For comparison, the population of San Bruno was 6,519 in 1940,[4] and the entire population of San Mateo County that year was 111,782.[5] There were approximately 1,600 children detained at Tanforan,[6] of which 110 were under one year old.[7]

According to the Final Report authored by John L. DeWitt, the cost of constructing the detention facilities at Tanforan was US$1,147,216 (equivalent to $20,550,000 in 2022).[3]: 349 Frank L. Davis served as the director of Tanforan Assembly Center, overseeing five departments (Administration, Works and Maintenance, Finance and Records, Mess and Lodging, and Service). Davis previously was the assistant state director of the Works Progress Administration and was named director in March.[6][8]: 7 An internal report was critical of each division in turn: the Administrative Division was responsible for "thoroughly censoring" the newspaper and "every other activity of the residents";[8]: 7 Supply, reporting to the Administrative Division, was "often charged with favoritism and 'graft'";[8]: 7 Works and Maintenance was "for a long time one of the most inefficient groups" until it was reorganized with a Japanese foreman;[8]: 7 Mess and Lodging had included one person who had failed to order adequate rations for May and June;[8]: 8 and Service "was entirely disorganized" in relation to detainee employment.[8]: 11

Within the Assembly Center, detainees were organized into blocks with a single House Manager. These were detainees appointed to help the Caucasian administrators by representing their groups of five to ten barracks or a single stall building; their primary responsibilities were to relay complaints from and order supplies for their residents.[8]: 9 The internal police were tasked with searching people and baggage during induction to ensure that no contraband items were being smuggled and maintaining the safety of the detainees. Initially, the force consisted mainly of young detained men who failed to impress: "[They] took advantage of their position to eat wherever they chose and to get into any place that they wanted. They did not patrol the beats as they were supposed to for it was very cold and their friends along the way were always available for bull sessions."[8]: 21 They were replaced by 13 Caucasian patrolmen, supplemented by Japanese-American quarantine officers, messenger boys, and guides.[8]: 22

Life in Tanforan

The assembly centers were temporary detention facilities at sites selected to allow the federal government to remove Japanese-Americans from the West Coast as quickly as possible while allowing time for more permanent relocation centers to be built in the interior. Racetracks and fairgrounds were chosen, as they typically had on-site utilities, spacious grounds, and facilities that could be adapted for housing thousands of people.[9]: 69 Sites "close to home" were chosen so that detainees could settle last-minute financial matters, minimize travel distances, and grow acclimated to group living.[9]: 72

According to an Army spokesman, "there wasn't time—there literally wasn't time—to segregate the loyal from the disloyal."[6] One administrative officer summed up his feelings about the detainees after three months of internment: "... no one can tell you what a Japanese is thinking. I know less about them right now than the first day I came here."[10] On the other hand, a detained college student noted that elementary school students onsite turned in "themes with the terms, 'treacherous Japs.' Apparently many of the kids get their education from Superman," describing the hyper-patriotism among many detainees.[10]

Clarence Sadamune escaped detention at Tanforan in May 1942 by telling the guards he was not Japanese. At the time, visitors to the assembly center were allowed, but were required to obtain a pass to enter and leave the grounds. Sadamune, who was half-Portuguese, told the guard at the gate that he had lost his pass and was allowed to leave. After he left, he took a bus to San Francisco and attempted to enlist in four different branches of the military, but was rejected when he told the recruiters he was half-Japanese. He purchased poison at a local drugstore and ingested it at the Army recruiting station; he was treated, then returned to Tanforan, then was sent to Arizona as a "troublemaker".[9]: 83

Housing and facilities

At Tanforan, Japanese-American detainees were housed in stalls previously used as horse stables, in the grandstand, or in temporary barracks quickly built in the infield. In total, there were 180 buildings on site: 26 converted stables and 154 new barracks; of those, five were condemned and not used, one was used as the headquarters for the center's recreational activities, and another one was used as the library.[8]: 3 The Wartime Civil Control Administration allotted 200 sq ft (19 m2) of living area per couple, but in practice each person had a space from 40 to 50 sq ft (3.7 to 4.6 m2), with families of eight housed in quarters that were just 20 ft × 20 ft (6.1 m × 6.1 m).[9]: 73

Because the infield barracks were still being constructed, the first detainees were housed in converted horse stalls, hastily updated for humans with minimal cleaning and amenities, as evidenced by the insects and dung trapped in whitewashed surfaces.[9]: 75 In many cases, the floor was dirty and no brooms were available to sweep them out.[8]: 39 The converted stalls were converted into two-room dwellings, measuring approximately 7 ft × 9 ft (2.1 m × 2.7 m) and 12 ft × 10 ft (3.7 m × 3.0 m).[8]: 4 Bachelors initially were housed in the grandstand area,[9]: 74 but were moved into outlying barracks in the last week of May.[8]: 5 Larger families were assigned to the newly-built barracks, although with dividers reaching only 3⁄4 of the way to the ceiling, privacy was minimal, and the hasty construction showed in gaps that let in the prevailing winds.[9]: 77 Each of the barracks held 30 people, divided into either 5 or 10 apartments;[8]: 4 each building measured 20 ft × 100 ft (6.1 m × 30.5 m).[6] Detainees used scrap lumber and improvised cleaning tools to build furniture and maintain their living spaces.[8]: 40–41 1,135 visitors were recorded between May 14 and 24, most bearing gifts of food, cleaning supplies, toilet paper, and treats in response to requests from the detainees.[8]: 44

Initially, all the detainees were served at a single mess hall at the grandstand; as Isabel Miyata recalled, "Everyone goes early to stand in line — if you don't you don't get a table or your share of the food. So the meals get earlier every day and you get hungry before you go to bed."[9]: 79 The grandstand mess was the sole source of food for Tanforan's first week and a half.[8]: 24 On average, the cost of rations for one detainee per day at Tanforan was US$0.37 (equivalent to $6.63 in 2022), slightly less than the $0.38 average for all assembly centers;[3]: 187 by August, Tanforan was serving 23,300 meals per day, averaging 6,480 lb (2,940 kg) of bread, 1,160 lb (530 kg) of butter, 2,720 dozens of eggs, 6,410 US gal (24,300 L) of milk, 2,880 lb (1,310 kg) of meat, and 2,520 lb (1,140 kg) of vegetables.[6]

The first meals were Army "A" and "B" rations[8]: 5 and showed little cultural consideration; rather than fish and rice, the first mess manager ordered chili con carne and sauerkraut. Several detainees remembered the Jell-O served: "We lined up at the Grand Mess Hall over there, and we had the JELL-O, the hardest JELL-O you can ever have ... We could throw it on the floor, and it would bounce back and make faces at you. It was the worst thing."[9]: 80 By the end of May, 10 additional mess halls were in operation to supplement the main mess hall.[8]: 5 However, many hungry young men would eat multiple meals by visiting different mess halls; house managers were forced to watch the people entering the mess to ensure that only the intended residents were served. Eventually, a colored ticket system was implemented to control mess access.[8]: 26 By August, 19 individual mess halls had been built, each staffed by detainees who prepared and served the meals under Caucasian supervision; the grandstand kitchen was converted into a cooking school and bakeshop.[6] Because each mess hall was unable to serve all the residents in its block, meals were split into two shifts; the first shift would be served at 7 a.m., 12 noon, and 5 p.m., and the second shift would be served 45 minutes later. Some detainees grumbled the second shift was more desirable, as they were allowed to finish off any leftover food.[8]: 26

Approximately 2,300 detainees were employed in work crews, performing maintenance, cleanup, and cooking.[11] The wages were announced on May 13 at US$8 (equivalent to $140 in 2022) per month for unskilled workers, rising to US$12 (equivalent to $210 in 2022) for skilled workers and US$18 (equivalent to $320 in 2022) for technical or professional jobs.[8]: 30

Onsite sanitation was difficult. Aside from living quarters converted from horse stalls, the rainy spring weather meant that internees had to slog through muddy lanes, and the accumulated manure and poorly drained sewage gave the center an offensive stench.[9]: 78 The first large group arrived on April 30; it rained all day, soaking the ground into mud and leaving the luggage drenched.[8]: 39 There were 24 latrines in the camp when it opened, 12 each for men and women. Of those, half had 16 toilets, and the other half had 8. Eventually, 42 latrines were built by the end of May.[8]: 3 Food poisoning incidents were common; in one case, the busy pace of nighttime latrine use led the guards to suspect that a rebellion was being plotted.[9]: 81 Only one shower room was built by May 1, and even then, no hot water was available for a week and a half.[8]: 39 The latrines themselves were built with limited privacy features; half-walls separated toilets and communal sinks and showers, forcing detainees to build makeshift tubs and dividers.[9]: 82

Education and activities

The head physician at Tanforan was Dr. Kay Kitagawa, who prior to his detention had practiced medicine in San Francisco.[12] Dr. Kazue Togasaki was detained for a month at the Tanforan Assembly Center, and while there she delivered fifty babies and led an all-Japanese-American medical team.[13][14] Togasaki was one of three sisters, all doctors; her sisters were detained at Manzanar and Poston.[12] Other detained physicians on the medical center staff included Dr. Eugenia Fujita, serving as the pediatrician, and Dr. Benjamin Kondo, cardiologist.[12]

During the detention at Tanforan, there were 64 births and 22 deaths.[3]: 202 On May 31, a baby was born prematurely and died while being transferred to the County Hospital due to the delays from clearing site administrative procedures.[8]: 23–24 The birthing center was an empty barrack with no partitions;[8]: 23 in total there were five barracks set aside for medical purposes, with rotating functions due to inadequate space and equipment.[8]: 24

Artist Miné Okubo was detained at Tanforan before transferring to the Topaz Relocation Center. She documented the daily life in internment camps with a series of drawings, many which were later published in her graphic memoir Citizen 13660.[15] Other notable artists detained at Tanforan included George and Hisako Hibi and UC Berkeley professor Chiura Obata and his family.[3]: 208 Shortly after being detained, Obata proposed to start an art school, which was granted by the administrators and taught by sixteen artists, including Okubo and the Hibis.[16][17] For administering and teaching at the art school, which operated twelve hours a day and included 636 students, ranging from elementary school students to adults, Obata received US$16 (equivalent to $290 in 2022) per week.[16] Kay Sekimachi took her initial art training at Tanforan.[16] Tanforan also had a music school with approximately 500 students.[11] The music program held a weekly Music Hour for the residents, with the loan period being three days for books.[8]: 13

The art and music programs were incorporated into a more formal education program. Starting on May 25, children between the ages of 6 and 18 were registered for the program, and instruction began the next day.[8]: 16 By August, onsite elementary (headed by Ernest Takahashi), junior high (John Izumi), and high schools (Henry Tani) had been set up, educating approximately 1,600 children at Tanforan. An adult school under Mrs. Tomoye Takahashi also was started to educate the Issei and Kibei, many of whom did not speak English.[12] A nursery school served approximately 90 children between ages 2 and 5, six days a week.[8]: 15 In total, there were 3,000 students enrolled in Tanforan's schools.[11] The library at Tanforan started with 50 books, and grew to 4,000 donated volumes under the leadership of librarian Kyoko Hoshiga, who had attended Mills College.[12] The first donations were provided by Mills and the Y.M.C.A.[8]: 15

Between May and September, detainees published 19 issues of the Tanforan Totalizer, an internal newsletter for the Assembly Center. Each issue has been digitized and is available online through the Library of Congress.[18] Taro Katayama was chief editor of the Totalizer, heading a staff that included Jim Yamada, Lillian Ota, and Charles Kikuchi,[12] whose diary detailing life at Tanforan would be published in 1973.[19] Initially, the post office at Tanforan required detainees to come in to pick up their mail; delivery to residences started on May 4 and as residents began to request or order and receive packages from friends and retailers, more than 6,000 pieces of mail were being handled per day within two weeks.[8]: 17–18

For recreation, the detainees set up 109 baseball teams and recreation centers;[11] a pond was built in the infield, holding races with model sailboats.[7] There were three troops of Boy Scouts; although Japanese cultural activities were "not suppressed by the Caucasian administration ... they [were] not given the attention received by American types", with typical recreational center activities including bridge, checkers, chess, boxing, and dancing.[7] Some mothers complained about how late their daughters had returned after the first dance, held May 9.[8]: 14 Talent shows were well-attended, with some audiences ranging from 2,000 to 5,000;[7] these were held every Thursday night and lasted for 90 minutes.[8]: 14

Closure

Starting on September 9, 1942, the first group of 214 detainees were sent from Tanforan to permanent detention at the Topaz War Relocation Center (aka Central Utah Relocation Center), a journey taking two days by train.[3]: 283 Groups of approximately 500 detainees each followed, starting on September 15, 1942; one group was sent per day until September 22, when approximately 4,400 in total had been transferred.[3]: 283 [20] The remaining 3,500 were relocated to Topaz beginning on September 26, again using daily trains of 500 detainees;[2] the last train left Tanforan on October 13, carrying 308 detainees.[3]: 283 After the Assembly Center was emptied, the site was turned over to the Northern California Sector of the Western Defense Command on October 27;[3]: 184 the Army used it for "commando training" before transferring the site to the United States Navy in June 1943.[21]

Memorials

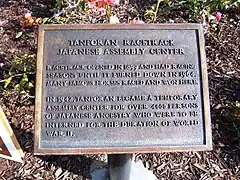

Initial memorial plaque (c. 1980)

Initial memorial plaque (c. 1980) Subsequent memorial plaque (2007)

Subsequent memorial plaque (2007) Dorothea Lange's photo of the Mochida family waiting for the bus in Hayward (1942). Hiroko and Miyuki are in the front row, at left; Miyuki is holding a sandwich. The children are wearing tags with the family number to help keep them together.

Dorothea Lange's photo of the Mochida family waiting for the bus in Hayward (1942). Hiroko and Miyuki are in the front row, at left; Miyuki is holding a sandwich. The children are wearing tags with the family number to help keep them together. Tanforan Memorial Plaza (2022)

Tanforan Memorial Plaza (2022)

After World War II, the site resumed its former use as a racetrack (1947–63), then as The Shops at Tanforan, a shopping mall (1971–2022), and as a BART station (2005+).[9]: 72 Thirteen Temporary Detention Camps for Japanese Americans in California were collectively designated California Historical Landmarks on May 13, 1980; Tanforan is CHL Number 934.09 and a memorial plaque was placed at the mall around this time.[22] After the mall completed its remodeling in 2005, the memorial plaque was moved to a site near the entrance facing El Camino Real. A second plaque was dedicated in September 2007, marking the site as a memorial garden.

In March 2012, the Tanforan Assembly Center Memorial Committee was formed to exhibit photographs of detainees at Tanforan on the concourse level of the San Bruno BART station;[23] the photographs were drawn from those taken by famed documentary photographer Dorothea Lange in 1942 and some were paired with photographs of the same detainees taken decades later by Sacramento Bee photographer Paul Kitagaki Jr.[24] The exhibit was staged to commemorate the 70th anniversary of the Tanforan Assembly Center,[23] and later became a traveling exhibition named Gambatte! Legacy of an Enduring Spirit.[25]

The installation at the San Bruno station was made permanent in 2016 as the Tanforan Assembly Center Memorial,[26] with plans to add a plaza outside the station.[27] When complete, the memorial plaza will include a bronze statue depicting Hiroko and Miyuki Mochida of Hayward, inspired by one of Lange's photographs taken while the Mochida family waited to board the bus to Tanforan.[28] The memorial plaza also will feature benches, seat walls, and a horse stall, representative of the housing conditions at Tanforan.[29] A groundbreaking ceremony for the new memorial was held on February 11, 2022, attended by U.S. Representative Jackie Speier and local officials and politicians;[30] the statue has been cast and is being stored while work progresses on the plaza. Both the statue and plaza were designed by Sandra J. Shaw.[29] The Tanforan Memorial plaza was dedicated on August 27, 2022.[31]

References

- "Army Acquires Tanforan". Organized Labor. April 11, 1942. Retrieved 22 February 2022.

- "Tanforan Center Being Cleared". Mill Valley Record. September 25, 1942. Retrieved 22 February 2022.

- DeWitt, John L. (1943). Final Report: Japanese Evacuation from the West Coast, 1942 (Report). Washington, D.C.: U.S. Government Printing Office. Retrieved 28 February 2022.

- "City of San Bruno, San Mateo County". Bay Area Census. Retrieved 28 February 2022.

- "San Mateo County". Bay Area Census. Retrieved 28 February 2022.

- Wahl, Kay (August 18, 1942). "Tanforan's Little Tokyo! How the Japanese react to strange test". San Francisco News. Retrieved 3 March 2022.

- Wahl, Kay (August 21, 1942). "Tanforan's Little Tokyo! More of what they do". San Francisco News. Retrieved 3 March 2022.

- Shibutani, Tamotsu; Najima, Haruo; Shibutani, Tomika (1942). The First Month at Tanforan (PDF) (Report). Tanforan Assembly Center. Retrieved 2 March 2022.

- Yamada, Gayle K; Fukami, Dianne (2003). "6: Tanforan Race Track: The first stop". In Wong, Diane Yen-Mei (ed.). Building a community: the story of Japanese Americans in San Mateo County. San Mateo, California: AACP, Inc. pp. 69–107. ISBN 0-934609-10-1.

- Wahl, Kay (August 22, 1942). "Tanforan's Little Tokyo! Are they loyal?". San Francisco News. Retrieved 3 March 2022.

- Wahl, Kay (August 20, 1942). "Tanforan's Little Tokyo! What they do". San Francisco News. Retrieved 3 March 2022.

- Wahl, Kay (August 19, 1942). "Tanforan's Little Tokyo! The people who are there". San Francisco News. Retrieved 3 March 2022.

- "America Has a Long History of Pitting Politics Against Public Health". Bitch Media.

- "Dysentery, Dust, and Determination: Health Care in the World War II Japanese American Detention Camps".

- Woo, Elaine (2001-03-04). "Mine Okubo; Her Art Told of Internment". Los Angeles Times. ISSN 0458-3035. Retrieved 2017-08-03.

- Ueno, Rihoko (September 10, 2019). "One Spot of Normalcy: Chiura Obata's Art Schools". Smithsonian Archives of American Art. Retrieved 2 March 2022.

- Wood, Cirrus (March 15, 2016). "Artist Interned: A Berkeley Legend Found Beauty in 'Enormous Bleakness' of War Camp". Cal Alumni Association. Retrieved 2 March 2022.

- "Tanforan Totalizer ([San Bruno, Calif.]) 1942–1942". Library of Congress. Retrieved 1 March 2022.

- Kikuchi, Charles (1973). Modell, John (ed.). The Kikuchi Diary: chronicle from an American concentration camp. Urbana, Illinois: University of Illinois Press. ISBN 0-252-00315-2. LCCN 72-95003. Retrieved 3 March 2022.

- "500 Japs Leave for Utah Camp". San Pedro News Pilot. AP. September 16, 1942. Retrieved 22 February 2022.

- "Navy Takes Over Tanforan Track". San Pedro News Pilot. AP. June 3, 1943. Retrieved 22 February 2022.

- "CHL No. 934.09 Temporary Detenion Camp for Japanese Americans/Tanforan Assembly Center - San Mateo". California Historical Landmarks. April 2015. Retrieved 1 March 2022.

- "About Us". Tanforan Assembly Center Memorial Committee. Retrieved 17 February 2022.

- "Photographs by Dorothea Lange and Paul Kitagaki, Jr. (free)". Discover Nikkei. April 2012. Retrieved 1 March 2022.

- Yollin, Patricia (April 8, 2015). "A Photographer's Quest: Japanese-American Internment Then and Now". KQED. Retrieved 1 March 2022.

- "Podcast: Moving oral histories of Tanforan at BART's San Bruno Station" (Press release). Bay Area Rapid Transit. September 9, 2016. Retrieved 1 March 2022.

- "History Comes to Life in San Bruno" (Press release). County of San Mateo, Community Services. August 11, 2016. Retrieved 1 March 2022.

- Kayoko Ikuma. "Kay (Mochida) Ikuma" (Interview). Interviewed by Diana Tsuchida. Japanese American Museum of San Jose. Retrieved 17 February 2022.

- "Ground Broken for Tanforan Memorial Plaza". Rafu Shimpo. February 19, 2022. Retrieved 1 March 2022.

- Toledo, Aldo (February 11, 2022). "Bay Area Japanese internment memorial opens at BART station where 'assembly center' stood". San Jose Mercury News. Retrieved 17 February 2022.

- "Tanforan Memorial Ribbon-Cutting Ceremony" (Press release). Consulate-General of Japan in San Francisco. August 29, 2022. Retrieved 27 September 2022.

External links

- "Tanforan (detention facility)". Densho Encyclopedia.

- Tamiko Yamazaki letter, Tanforan Assembly Center, San Bruno, Calif, to Ruth E. Smith : ALS, 1942 July 10, The Bancroft Library

- Library, Tanforan Assembly, 42 [graphic], The Bancroft Library

- Hisako Hibi pictorial collection concerning the Tanforan Assembly Center and the Central Utah Relocation Center [graphic], The Bancroft Library

- Drawings of the Tanforan Assembly Center graphic / by S.Y. Saito., The Bancroft Library

- Calisphere (University of California) – master list of 147 images and 32 texts for Tanforan