Tanks in World War I

The development of tanks in World War I was a response to the stalemate that developed on the Western Front. Although vehicles that incorporated the basic principles of the tank (armour, firepower, and all-terrain mobility) had been projected in the decade or so before the War, it was the alarmingly heavy casualties of the start of its trench warfare that stimulated development.[1][2] Research took place in both Great Britain and France, with Germany only belatedly following the Allies' lead.

_tank.jpg.webp)

In Great Britain, an initial vehicle, nicknamed Little Willie, was constructed at William Foster & Co., during August and September 1915.[3] The prototype of a new design that became the Mark I tank was demonstrated to the British Army on 2 February 1916. Although initially termed "Landships" by the Landship Committee, production vehicles were named "tanks", to preserve secrecy. The term was chosen when it became known that the factory workers at William Foster referred to the first prototype as "the tank" because of its resemblance to a steel water tank.

The French fielded their first tanks in April 1917 and ultimately produced far more tanks than all other countries combined.

The Germans, on the other hand, began development only in response to the appearance of Allied tanks on the battlefield. Whilst the Allies manufactured several thousand tanks during the war, Germany deployed only 18 of its own.[4]

The first tanks were mechanically unreliable. There were problems that caused considerable attrition rates during combat deployment and transit. The heavily shelled terrain was impassable to conventional vehicles, and only highly mobile tanks such as the Renault FTs and Mark IV performed reasonably well. The Mark I's rhomboid shape, caterpillar tracks, and 26-foot (8 m) length meant that it could negotiate obstacles, especially wide trenches, that wheeled vehicles could not. Along with the tank, the first self-propelled gun (the British Gun Carrier Mk I) and the first armoured personnel carrier followed the invention of tanks.

Conceptual roots

The conceptual roots of the tank go back to ancient times, with siege engines that were able to provide protection for troops moving up against stone walls or other fortifications. With the coming of the Industrial Revolution and the demonstrable power of steam, James Cowan presented a proposal for a Steam Powered Land Ram in 1855, towards the end of the Crimean War. Looking like a helmet on 'footed' Boydell wheels, early forerunners of the Pedrail wheel, it was essentially an armoured steam tractor equipped with cannon and rotating scythes sprouting from the sides. Lord Palmerston is said to have dismissed it as 'barbaric'.

From 1904 to 1909, David Roberts, the engineer and managing director of Hornsby & Sons of Grantham, built a series of tractors using his patented 'chain-track', which were put through their paces by the British Army, a (small) section of which wanted to evaluate artillery tractors. At one point in 1908, Major William E. Donohue of the Mechanical Transport Committee remarked to Roberts that he should design a new machine with armour that could carry its own gun. However, disheartened by years of ultimately-fruitless tinkering for the Army, Roberts did not take up the idea. In later years, he expressed regret at not having pursued it.[5]

An engineer in the Austro-Hungarian Army, Lieutenant Gunther Burstyn, designed a tracked armoured vehicle in 1911 carrying a light gun in a rotating turret; equipped also with hinged 'arms', two in front and two at the rear, carrying wheels on the ends to assist with obstacles and trenches, it was a very forward-looking design, if rather small. The Austro-Hungarian government said that it would be interested in evaluating it if Burstyn could secure commercial backing to produce a prototype. Lacking the requisite contacts, he let it drop. An approach to the German government was similarly fruitless.

In 1912, Lancelot De Mole, of South Australia, submitted a proposal to the British War Office for a "chain-rail vehicle which could be easily steered and carry heavy loads over rough ground and trenches". De Mole made more proposals to the War Office in 1914 and 1916, with a culminating proposal in late 1917, accompanied by a huge one-eighth scale model, but all fell on substantially-deaf ears. De Mole's proposal already had the climbing face, which was so typical of the later World War I British tanks, but it is unknown whether there was some connection.

Inquiries to the government of Australia after the war yielded polite responses that Mr. De Mole's ideas had unfortunately been too advanced for the time to be properly recognised at their just value. The Commission on Awards to Inventors in 1919, which adjudicated all the competing claims to the development of the tank, recognised the brilliance of De Mole's design and even considered that it was superior to the machines actually developed, but its narrow remit allowed it only to make a payment of £987 to De Mole to cover his expenses. He noted in 1919 that he was urged by friends before the war to approach the Germans with his design but declined to do so for patriotic reasons.

Before World War I, motorised vehicles were still relatively uncommon, and their use on the battlefield was initially limited, especially of heavier vehicles. Armoured cars soon became more common with most belligerents, especially in more-open terrain. On 23 August 1914 the French Colonel Jean Baptiste Eugène Estienne, later a major proponent of tanks, declared, "Gentlemen, victory will belong in this war to the one of the two belligerents that will manage to be the first to succeed in putting a 75 mm cannon on a vehicle that can move on all types of terrain."

Armored cars indeed proved useful in open land, such as in deserts, but were not very good at crossing obstacles, such as trenches and barriers, or in more-challenging terrain. The other issue was that it was very hard to add much protection or armament.

The main limitation was the wheels, which gave a high ground pressure for the vehicle's weight. That could be solved by adding more wheels, but unless they also were driven, the effect was to reduce traction on the powered wheels. Driving extra wheels meant more drive train weight, which required a larger and heavier engine to maintain performance. Even worse, none of the extra weight was put into an improvement of armour or armament carried, and the vehicles could still not cross very rough terrain.

The adoption of caterpillar tracks offered a new solution to the problem. The tracks spread the weight of the vehicles over a much greater area, all of which was for traction to move the vehicle. The limitation on armour and firepower was no longer the ground pressure but the power and weight of the power-plant.

The remaining issue was how to use and configure a vehicle. Major Ernest Dunlop Swinton of the Royal Engineers was the official British war correspondent serving in France in 1914 and recounted in his book Eyewitness how the idea of using caterpillar tracks to drive an armoured fighting vehicle came to him on 19 October 1914 while he was driving through northern France. In July 1914, he had received a letter from a friend, Hugh Marriott, a mining engineer, who drew his attention to a Holt caterpillar tractor that Marriott had seen in Belgium.

Marriott thought that it might be useful for transport over difficult ground, and Swinton had passed the information on to the appropriate departments. Swinton then suggested the idea of an armoured tracked vehicle to the military authorities by sending a proposal to Lieutenant-Colonel Maurice Hankey, who tried to interest Lord Kitchener in the idea. When that failed, he sent a memorandum in December to the Committee of Imperial Defence, of which he was himself the secretary. Winston Churchill the First Lord of the Admiralty was one of the members of the committee. Hankey proposed to build a gigantic steel roller pushed by tracked tractors to shield the advancing infantry.

Churchill, in turn, wrote a note on 5 January to Prime Minister H. H. Asquith and warned that the Germans might any moment introduce a comparable system. A worried Asquith now ordered Kitchener to form a committee, headed by General Scott-Moncrieff, to study the feasibility of Swinton's idea; however, after trials with a Holt 75 horsepower machine, the committee concluded in February 1915 that the idea was impractical.

Landship Committee

Churchill, however, decided that unless the Army took up the idea, the Navy should proceed independently, even if it exceeded the limits of his authority. He created the Landship Committee in February 1915, initially to investigate designs for a massive troop transporter. As a truer picture of front-line conditions was developed the aims of the investigation changed. A requirement was formulated for an armoured vehicle capable of 4 mph (6.4 km/h), climbing a 5 feet (1.5 m) high parapet, crossing an 8 feet (2.4 m) wide gap, and armed with machine guns and a light artillery piece.

A similar proposal was working its way through the Army GHQ in France, and in June, the Landships Committee was made a joint service venture between the War Office and the Admiralty. The Naval involvement in Armoured Fighting Vehicle (AFV) design had originally come about through the Royal Naval Air Service Armoured Car Division, the only British unit fielding AFVs in 1914. Surprisingly, until the end of the war, most experimentation on heavy land vehicles was conducted by the Royal Naval Air Service Squadron 20.

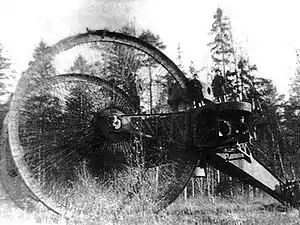

At first, protecting heavy gun tractors with armour appeared the most promising line of development. Alternative early 'big wheel' designs on the lines of the Russian tsar tank of 1915 were soon understood to be impractical. However, adapting the existing Holt Company caterpillar designs, the only robust tracked tractors available in 1915 into a fighting machine, which France and Germany did, was decided against. Although armour and weapon systems were easy to acquire, other existing caterpillar and suspension units were too weak, existing engines were underpowered for the vehicles that the designers had in mind and the ability to cross trenches was poor because of the shortness of the wheelbase.

The Killen-Strait tractor with three tracks was used for the first experiments in June but was much too small to be developed further. The large Pedrail monotrack vehicle was proposed in a number of different configurations, but none were adopted. Trials to couple two American Bullock tractors failed. There also were considerable differences of opinion between the several committee members. Col R.E.B. Crompton, a veteran military engineer and electrical pioneer, drafted numerous designs with Lucien Legros for armoured troop carrying vehicles and gun-armed vehicles, to have used either Bullock tracks or variants of the Pedrail.

At the same time, Lt Robert Macfie, of the RNAS, and Albert Nesfield, an Ealing-based engineer, devised a number of armoured tracked vehicles, which incorporated an angled front 'climbing face' to the tracks. The two men fell out bitterly as their plans came to nought; Macfie in particular pursued a vendetta against the other members of the Landships Committee after the war.

To resolve the threatened dissipation of effort, it was ordered in late July that a contract was to be placed with William Foster & Co. Ltd, a company having done some prewar design work on heavy tractors and known to Churchill from an earlier experiment with a trench-crossing supply vehicle, to produce a proof-of-concept vehicle with two tracks, based on a lengthened Bullock tractor chassis. Construction work began three weeks later.

Fosters of Lincoln built the 14 ton "Little Willie", which first ran on 8 September. Powered by a 105 hp (78 kW) Daimler engine, the 10-foot-high (3.0 m) armoured box was initially fitted with a low Bullock caterpillar. A rotating top turret was planned with a 40 mm gun but abandoned due to weight problems, leaving the final vehicle unarmed and little more than a test-bed for the difficult track system. Difficulties with the commercial tracks supplied led to Tritton designing a completely new track system different from, and vastly more robust than, any other system then in use.

The next design by Lieutenant Walter Gordon Wilson RNAS, a pre-war motor engineer, added a larger track frame to the hull of "Little Willie". In order to achieve the demanded gap clearance a rhomboidal shape was chosen—stretching the form to improve the track footprint and climbing capacity. To keep a low centre of gravity the rotating turret design was dropped in favour of sponsons on the sides of the hull fitted with naval 6-pounder (57 mm) guns.

A final specification was agreed on in late September for trials in early 1916, and the resulting 30 ton "Big Willie" (later called "Mother") together with "Little Willie" underwent trials at Hatfield Park on 29 January and 2 February. Attendees at the second trial included Lord Kitchener, Lloyd George, Reginald McKenna and other political luminaries. On 12 February an initial order for 100 "Mother" type vehicles was made, later expanded to 150.

Crews rarely called tanks "Willies"; at first they referred to them as "cars", and later informally "buses".[6] Although landship was a natural term coming from an Admiralty committee, it was considered too descriptive and could give away British intentions. The committee, therefore, looked for an appropriate code term for the vehicles. Factory workers assembling the vehicles had been told they were producing "mobile water tanks" for desert warfare in Mesopotamia. Water Container was therefore considered but rejected because the committee would inevitably be known as the WC Committee (WC meaning water closet was a common British term for a toilet).

The term tank, as in water tank, was in December 1915 accepted as its official designation. From then on, the term "tank" was established among British and also German soldiers. While in German Tank specifically refers to the World War I type (as opposed to modern Panzer), in English, Russian and other languages the name even for contemporary armored vehicles is still based on the word tank.

It is sometimes mistakenly stated that, after completion, the tanks were shipped to France in large wooden crates. For secrecy and in order to not arouse any curiosity, the crates and the tanks themselves were then each labeled with a destination in Russian, "With Care to Petrograd". In fact, the tanks were never shipped in crates: the inscription in Russian was applied on the hull for their transport from the factory to the first training centre at Thetford.

The first fifty had been delivered to France on 30 August. They were 'male' or 'female', depending upon whether their armament comprised two 6-pounder cannons and three Hotchkiss machine guns or four Vickers machine guns and one Hotchkiss. It had a crew of eight, four of whom were needed to handle the steering and drive gears. The tanks were capable of, at best, 6 km/h (3.7 mph), matching the speed of marching infantry with whom they were to be integrated to aid in the destruction of enemy machine guns. In practice, their speed on the broken ground could be as little as 1 mph.

After the war the Royal Commission on Awards to Inventors decided that the principal inventors of the Tank were Sir William Tritton, managing director of Fosters, and Major Walter Gordon Wilson. Fosters returned to manufacturing Traction engines and steam lorries, but incorporated a small trademark outline image of a tank on the front smokebox door of their postwar road locomotives. During WWII, Tritton and Wilson were called upon to design a Heavy tank, which was known as TOG1, (named for "The Old Gang"), but this was not a success. However, Lincoln City erected a full-size outline Mk 1 as a memorial to the invention of the tank in 2015, and placed it on the Tritton Road roundabout.

First deployments

_tank.jpg.webp)

For secrecy, the six new tank companies were assigned to the Heavy Section of the Machine Gun Corps.[6] The first use of tanks on the battlefield was the use of British Mark I tanks by C and D Companies HS MGC at the Battle of Flers-Courcelette (part of the Battle of the Somme) on Friday 15 September 1916, with mixed results. Many broke down, but nearly a third succeeded in breaking through. Of the forty-nine tanks shipped to the Somme, only thirty-two were able to begin the first attack in which they were used, and only nine made it across "no man's land" to the German lines. The tanks had been rushed into combat before the design was mature enough (against the wishes of Churchill and Ernest Swinton)[7] and the number was small but their use gave important feedback on how to design newer tanks, the soundness of the concept and their potential to affect the course of the war.

On the other hand, the French Army was critical of the British employment of small numbers of tanks at the battle. It felt the British had sacrificed the secrecy of the weapon but used it in numbers too small to be decisive. Since the British attack was part of an Anglo-French offensive, and the Russians were attacking at the same time, Haig felt justified in making a maximum effort, regardless of the limitations of the tank force.

Tank crews who had read press reports depicting the new weapon driving through buildings and trees, and crossing wide rivers, were disappointed.[6] The Mark I's were nonetheless capable of performing on the real battlefield of World War I, one of the most difficult battlefield terrains in history. Despite their reliability problems, when they worked, they could cross trenches or craters of 9 feet (2.7 m) and drive right through barbed wire. It was still common for them to get stuck, especially in larger bomb craters, but overall, the rhomboid shape allowed for extreme terrain mobility.

.jpg.webp)

Most World War I tanks could travel only at about a walking pace at best. Their steel armour could stop small arms fire and fragments from high-explosive artillery shells. However, they were vulnerable to a direct hit from artillery and mortar shells. The environment inside was extremely unpleasant; as ventilation was inadequate the atmosphere was heavy with poisonous carbon monoxide from the engine and firing the weapons, fuel and oil vapours from the engine and cordite fumes from the weapons. Temperatures inside could reach 50°C (122°F). Entire crews lost consciousness inside the tanks, or collapsed when again exposed to fresh air.[8] Crews learned how to create and leave behind supply dumps of fuel, motor oil, and tread grease, and converted obsolete models into supply vehicles for newer ones.[6]

To counter the danger of bullet splash or fragments knocked off the inside of the hull, the crew wore helmets with goggles and chainmail masks. Fragments were not as dangerous as fire, because of explosive fumes and the large amount of fuel aboard; smoking was prohibited inside and within 20 yards outside tanks.[6] Gas masks were also standard issue, as they were to all soldiers at this point in the war due to the use of chemical warfare. The side armour of 8 mm initially made them largely immune to small arms fire, but could be penetrated by the recently developed armour-piercing K bullets.

There was also the danger of being overrun by infantry and attacked with grenades. The next generation had thicker armour, making them nearly immune to the K bullets. In response, the Germans developed a larger purpose-made anti-tank rifle, the 3.7 cm TAK 1918 anti-tank gun, and also a Geballte Ladung ("Bunched Charge")—several regular stick grenades bundled together for a much bigger explosion.

Engine power was a primary limitation on the tanks; the roughly one hundred horsepower engines gave a power-to-weight ratio of 3.3 hp/ton (2.5 kW/ton). By the end of the 20th century, power-to-weight ratios exceeded 20 hp/ton (15 kW/ton).

Many feel that because the British Commander Field Marshal Douglas Haig was himself a horse cavalryman, his command failed to appreciate the value of tanks. In fact, horse cavalry doctrine in World War I was to "follow up a breakthrough with harassing attacks in the rear", but there were no breakthroughs on the Western Front until the tanks came along. Despite these supposed views of Haig, he made an order for 1,000 tanks shortly after the failure at the Somme and always remained firmly in favour of further production.

In 1919, Major General Sir Louis Jackson said: "The tank was a freak. The circumstances which called it into existence were exceptional and not likely to recur. If they do, they can be dealt with by other means."[9]

French developments

France at the same time developed its own tracked AFVs, but the situation there was very different. In Britain a single committee had coordinated design, and had to overcome the initial resistance of the Army, while the major industries remained passive. Almost all production effort was thus concentrated into the Mark I and its direct successors, all very similar in shape. In France, on the other hand, there were multiple and conflicting lines of development which were badly integrated, resulting in three major and quite disparate production types.

A major arms producer, Schneider, took the lead in January 1915 and tried to build a first armoured vehicle based on the Baby Holt tractor but initially the development process was slow until in July they received political, even presidential, support by combining their project with that of a mechanical wire cutter devised by engineer and politician Jean-Louis Bréton. In December 1915, the influential Colonel Estienne made the Supreme Command very enthusiastic about the idea of creating an armoured force based on these vehicles; strong Army support for tanks was a constant during the decades that followed. Already in January and February 1916, quite substantial orders were made at that moment with a total number of 800, much larger than the British ones.

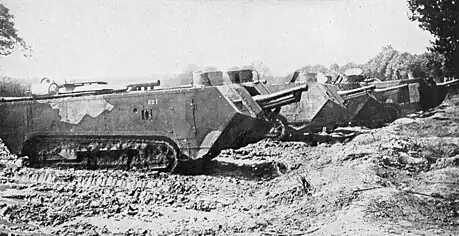

Army enthusiasm and haste had its immediate drawbacks however. As a result of the involvement of inexperienced army officers ordered to devise a new tank based on the larger 75 hp Holt chassis in a very short period of time, the first French tanks were poorly designed with respect to the need to cross trenches and did not take the sponson-mounting route of the British tanks. The first, the Char Schneider CA equipped with a short 75 mm howitzer, had poor mobility due to a short track length combined with a hull that overhung both front and rear.

It was unreliable as well; a maximum of only about 130 of the 400 built were ever operational at the same time. Then industrial rivalry began to play a detrimental role: it created the heavy Char St Chamond, a parallel development not ordered by the Army but approved by government through industrial lobbying, which mounted much more impressive weaponry—its 75mm was the most powerful gun fielded by any operational tank up until 1941—but also combined many of the Schneider CA's faults with an even larger overhanging body. Its innovative petro-electrical transmission, while allowing for easy steering, was insufficiently developed and led to a large number of breakdowns.

But industrial initiative also led to swift advances. The car industry, already used to vehicle mass production and having much more experience in vehicle layout, designed the first practical light tanks in 1916, a class largely neglected by the British. It was Renault's excellent small tank design, the FT, incorporating a proper climbing face for the tracks, that was the first tank to incorporate a top-mounted turret with a full 360° traverse capability.

The FT was in many respects the first truly 'modern' tank, having a layout that has been followed by almost all designs ever since: driver at the front; main armament in a fully rotating turret on top; engine at the rear. Previous models had been "box tanks", with a single crowded space combining the role of engine room, fighting compartment, ammunition stock and driver's cabin. (A very similar Peugeot prototype, with a fixed casemate mounting a short 75mm cannon, was trialed in 1918 but the idea was not pursued). The FT had the largest production run of any tank of the war, with over 3700 built, more numerous than all British and German tanks combined. That this would happen was at first far from certain; some in the French army lobbied for the alternative mass production of super-heavy tanks.

Much design effort was put in this line of development resulting in the gigantic Char 2C, the most complex and technologically advanced tank of its day. Its very complexity ensured it being produced too late to participate in World War I and in the very small number of just ten, but it was the first tank with a three-man turret; the heaviest to enter service until late in World War II and still the largest ever operational tank.

French production at first lagged behind the British. After August 1916 however, British tank manufacture was temporarily halted to wait for better designs, allowing the French to overtake their allies in numbers. When the French used tanks for the first time on 16 April 1917, during the Nivelle Offensive, they had four times more tanks available. But that did not last long as the offensive was a major failure; the Schneiders were badly deployed and suffered 50% losses from German long-range artillery. The Saint-Chamond tanks, first deployed on 5 May, proved to be so badly designed that they were unable to cross the first line of German trenches.

German developments

Germany concentrated more on the development of anti-tank weapons than on development of tanks themselves. They only developed one type of tank which saw combat in the war. The A7V Sturmpanzerwagen was designed in 1917 and was used in battle from March 1918. It was manned by a crew of 18, and had eight machine guns and a 57-millimetre cannon. Only 20 A7Vs were produced during the war. The Germans did, however, capture Allied tanks and re-purpose them for their own uses.

Battle of Cambrai

The first battle in which tanks made a great impact was the Battle of Cambrai in 1917. British Colonel J.F.C. Fuller, chief of staff of the Tank Corps, was responsible for the tanks' role in the battle. They made an unprecedented breakthrough but the opportunity was not exploited. Ironically, it was the soon-to-be-supplanted horse cavalry that had been assigned the task of following up the motorised tank attack.[10]

Tanks became more effective as the lesson of the early tanks was absorbed. The British produced the Mark IV in 1917. Similar to the early Marks in appearance, its construction was considered to produce a more reliable machine; the long-barrelled naval guns were shortened, (the barrels of the earlier, longer guns were prone to digging in the mud when negotiating obstacles) and armour was increased just enough to defeat the standard German armour-piercing bullet.

The continued need for four men to drive the tank was solved with the Mark V which used Wilson's epicyclic gearing in 1918. Also in 1918 the French produced the Renault FT, the result of a co-operation between Estienne and Louis Renault. As mentioned before, it had the innovative turret position, and was operated by two men. At just 8 tons it was half the weight of the Medium A Whippet but the version with the cannon had more firepower. It was conceived for mass production, and the FT became the most produced tank of World War I by a wide margin, with over 3,000 delivered to the French Army. Large numbers were also used by the Americans and several were lent to the British.

In July 1918, the French used 480 tanks (mostly FTs) at the Battle of Soissons, and there were even larger assaults planned for the next year. In Plan 1919, the Entente hoped to commit over 30,000 tanks to battle in that year.

Whippet

Finally, in a preview of later developments, the British developed the Whippet. This tank was specifically designed to exploit breaches in the enemy front with its relatively higher speed (around 8 mph vs 3–4 mph for the British heavy tanks). The Whippet was faster than most other tanks, although it carried only machine gun armament, meaning it was not suited to combat with armoured vehicles but instead with infantry. Postwar tank designs reflected this trend towards greater tactical mobility.

Villers-Bretonneux: Tank against tank

The German General Staff did not have enthusiasm for tanks but allowed the development of anti-tank weapons. Regardless, the development of a German tank was underway. The only project to be produced and fielded was the A7V, although only twenty were built. The majority of the fifty or so tanks fielded by Germany were captured British vehicles. A7Vs were captured by the Allies, but they were not used, and most ended up being scrapped.

The first tank-versus-tank battles took place on 24 April 1918. It was an unexpected engagement between three German A7Vs and three British Mk. IVs at Villers-Bretonneux.

Fuller's Plan 1919, involving massive use of tanks for an offensive, was never used because the blockade of Germany and the entry of the US brought an end to the war.

See also

Notes and references

- Williamson Murray, "Armored Warfare: The British, French, and German Experiences," in Murray, Williamson; Millet, Allan R, eds. (1996). Military Innovation in the Interwar Period. New York: Cambridge University Press. p. 6. ISBN 0-521-63760-0.

- Harvey, A. D. (1992). Collision of Empires: Britain in Three World Wars, 1793–1945. A&C Black. ISBN 978-1852850784 – via Google Books.

- Watson, Greig (24 February 2014). "Hotel where warfare changed forever". BBC News.

- Showalter, D.E. "More Than Nuts And Bolts: Technology And The German Army, 1870–1945." Historian 65.1 (Fall 2002): 123–143. Academic Search Premier. Web. 16 February 2012.

- The Devil's Chariots: The Birth and Secret Battles of the First Tanks. John Glanfield (Sutton Publishing, 2001) p. 16

- Littledale, Harold A. (December 1918). "With the Tanks – I. Anatomy and Habitat". The Atlantic. pp. 836–848.

- "Sensing that tanks would only be effective if they involved an element of surprise, he pressed the government not to use them in small numbers in the Battle of the Somme. As he had put it in a memorandum in 1915, 'None should be used until all can be used at once'. Despite his objections, thirty-five (sic) tanks were used in September 1916, but to very little effect. 'My poor "land battleships" have been let off prematurely and on a petty scale,' he wrote." Havardi, J. The Greatest Briton: Essays on Winston Churchill's Life and Political Philosophy. Shepheard-Walwyn, 2010. ISBN 0856832650

- Macpherson WG, Herringham WP, Elliot TR, Balfour A. History of the Great War Based on Official Documents: Medical Services Diseases of the War. Vol 2. London: His Majesty’s Stationery Office; 1923. in Weyandt, Timothy B. and Charles David Ridgely. "Carbon Monoxide." Occupational Health: The Soldier and the Industrial Base. 1993: Office of the Surgeon General, U.S. Department of the Army. pp. 402–403. Web. 16 Feb 2012

- Military Blunders, p. 152

- A.J. Smithers, Cambrai: The First Great Tank Battle (2014)

- Glanfield, John (2001) Devil's Chariots: the birth and secret battles of the first tanks. Stroud: Sutton

- Tucker, Spencer C. World War I: The Definitive Encyclopedia and Document Collection. Vol. 4. R-Z. 1536. Santa Barbara, CA: ABC-CLIO, LLC, 2014.

Further reading

- Charles River Editors and Colin Fluxman. The Tanks of World War I: The History and Legacy of Tank Warfare during the Great War (2017)

- Foley, Michael. Rise of the Tank: Armoured Vehicles and their use in the First World War (2014)

- Townsend, Reginald T. (December 1916). "'Tanks' And 'The Hose Of Death'". The World's Work: A History of Our Time: 195–207. Retrieved 2009-08-04.

- Kaplan, Lawrence M. ed. Pershing's Tankers: Personal Accounts of the AEF Tank Corps in World War I (University Press of Kentucky; 314 pages) primary sources; memoirs.

- Smithers, A.J. Cambrai: The First Great Tank Battle (2014)

- Zaloga, Steven J. and Tony Bryan. French Tanks of World War I (2010)

External links

- Lancelot De Mole's tank models Archived 2009-02-08 at the Wayback Machine

- WW1 Tanks (1914–1918)

- Kennedy, Michael David: Tanks and Tank Warfare 1914–1918 Online. International Encyclopedia of the First World War