Ternopil

Ternopil (Ukrainian: Тернопіль, IPA: [terˈnɔp⁽ʲ⁾ilʲ] ⓘ; Polish: Tarnopol; Yiddish: טארנאפאל, romanized: Tarnapol; Hebrew: טרנופול, romanized: Tarnopol; German: Tannstadt), known until 1944 mostly as Tarnopol, is a city in the west of Ukraine, located on the banks of the Seret. Administratively, it serves as the administrative centre of Ternopil Oblast. Ternopil is one of the major cities of Western Ukraine and the historical regions of Galicia and Podolia. It is served by Ternopil Airport. The population of Ternopil was estimated at 225,004 (2022 estimate).[2]

Ternopil

Тернопіль | |

|---|---|

| |

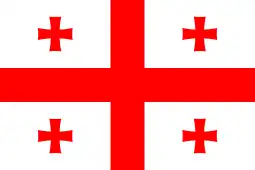

Flag  Coat of arms | |

Ternopil Location within Ukraine  Ternopil Ternopil (Ternopil Oblast) | |

| Coordinates: 49°34′N 25°36′E | |

| Country | |

| Oblast | |

| Raion | |

| Founded | 1540 (483 years ago) |

| Government | |

| • Mayor | Serhiy Nadal[1] (Svoboda) |

| Area | |

| • Total | 86 km2 (33.2 sq mi) |

| Elevation (mean) | 320 m (1,050 ft) |

| Population (2022)[2] | |

| • Total | 225,004 |

| • Density | 2,600/km2 (6,800/sq mi) |

| Time zone | UTC+2 (CET) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC+3 (CEST) |

| Area code | +380 352 |

| Website | rada |

Administrative status

The city is the administrative center of Ternopil Oblast (region), as well as of surrounding Ternopil Raion (district) within the oblast. It hosts the administration of Ternopil urban hromada, one of the hromadas of Ukraine.[3]

Until 18 July 2020, Ternopil was designated as a city of oblast significance and did not belong to Ternopil Raion even though it was the center of the raion. As part of the administrative reform of Ukraine, which reduced the number of raions of Ternopil Oblast to three, the city was merged into Ternopil Raion.[4][5]

History

The city was founded in 1540 by Polish commander and Hetman Jan Amor Tarnowski.[6] Its Polish name Tarnopol means 'Tarnowski's city' and stems from a combination of the founder's family name and the Greek term polis.[7][8] The city served as a military stronghold and castle [6] On 15 April 1540,[6] the King of Poland, Sigismund I the Old,[6] in Kraków gave Tarnowski permission to establish Tarnopol,[6] near Sopilcze (Sopilche).[6] protecting the eastern borders of Polish Kingdom from Tatar raids. In 1570, the city passed to the Ostrogski family,[6] and in 1623 to the Zamoyski family.[6] During the Khmelnytsky Uprising, many residents of the city joined the ranks of the Cossack forces.[9] During the 1672–1676 Polish–Ottoman War, Tarnopol was almost completely destroyed by Turkish forces of Ibrahim Shishman Pasha in 1675, then rebuilt by Aleksander Koniecpolski.[9]

In 1772, after the First Partition of Poland, the city came under Austrian rule. In 1809, after the War of the Fifth Coalition, the city came under Russian rule, incorporated into the newly created Ternopol krai, but in 1815 returned to Austrian rule in accordance with the Congress of Vienna. In 1870 Tarnopol was connected by railway with Lemberg.

During World War I the city passed from German and Austrian forces to Russia several times. In 1917, the city and its castle were burned down by fleeing Russian forces.[6] After the dissolution of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, the city was proclaimed as part of the West Ukrainian People's Republic on 11 November 1918. After Polish forces captured Lwów during the Polish-Ukrainian War, Tarnopol became the country's temporary capital.[10] After the act of union between the West Ukrainian Republic and the Ukrainian People's Republic, Ternopil formally became part of the UPR. On 15 July 1919, the city was captured.[10] by Polish forces. In July and August 1920 the Red Army captured Ternopil in the course of the Polish-Soviet War, and the city served as the capital of the short-lived Galician Soviet Socialist Republic. Under the terms of the Riga treaty, the area remained under Polish control.

As a consequence of the Soviet invasion of Poland in 1939, Ternopil was incorporated into the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic as part of Ternopol Oblast. On 2 July 1941, the city was occupied by the Nazis. Between then and July 1943, 10,000 Jews were killed by Nazi Germans, and another 6,000 were rounded up and sent to Belzec extermination camp. A few hundred others went to labor camps. During most of this time Jews lived in the Tarnopol Ghetto.[11][12] Many Ukrainians were sent as forced labour to Germany. Following the Act of restoration of the Ukrainian state proclaimed in Lviv on 30 June 1941, Ukrainian Insurgent Army (UPA) was active in Ternopil region and battled for the independence of Ukraine, opposing Nazis, Polish Armia Krajowa and People's Army of Poland as well as the Soviets. During the Soviet offensive in March and April 1944, the city was almost completely destroyed by Soviet artillery. [13] Finally, Ternopol was occupied by the Red Army on 15 April 1944. After the second Soviet occupation, 85% of the city's living quarters were destroyed.[6]

Following the Potsdam Conference in 1945, Poland's borders were redrawn and Ternopil was incorporated into the Ukrainian SSR of the Soviet Union. The ethnic Polish population of the area was forcibly deported to postwar Poland[14] In the following decades, Ternopil was rebuilt in a typical Soviet style and only a few buildings were reconstructed.

Following the fall of the Soviet Union, Ternopil became part of the independent Ukraine as a city of regional significance. On 31 December 2013, the 11th Artillery Brigade, descendant of artillery units that had been based in the city since 1949, was disbanded.[15] In 2020, as part of the administrative reform in Ukraine, which reduced the number of raions of Ternopil Oblast to three, the city was merged into Ternopil Raion.[16][17]

During the Russo-Ukrainian War, Ternopil was struck by Russian missiles on 13 May 2023, minutes before Ternopil natives Tvorchi performed at the Eurovision Song Contest 2023.[18]

Geography

Climate

Ternopil has a moderate continental climate with cold winters and warm summers.

| Climate data for Ternopil (1981–2010, extremes 1949–2011) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 12.2 (54.0) |

17.3 (63.1) |

25.0 (77.0) |

30.0 (86.0) |

30.2 (86.4) |

37.8 (100.0) |

38.4 (101.1) |

36.1 (97.0) |

32.1 (89.8) |

25.7 (78.3) |

19.9 (67.8) |

13.9 (57.0) |

38.4 (101.1) |

| Average high °C (°F) | −1.3 (29.7) |

0.0 (32.0) |

5.0 (41.0) |

13.2 (55.8) |

19.4 (66.9) |

21.7 (71.1) |

23.8 (74.8) |

23.5 (74.3) |

18.1 (64.6) |

12.3 (54.1) |

4.7 (40.5) |

−0.3 (31.5) |

11.7 (53.1) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | −3.9 (25.0) |

−3.0 (26.6) |

1.1 (34.0) |

8.0 (46.4) |

14.0 (57.2) |

16.6 (61.9) |

18.5 (65.3) |

17.8 (64.0) |

13.0 (55.4) |

7.7 (45.9) |

1.8 (35.2) |

−2.7 (27.1) |

7.4 (45.3) |

| Average low °C (°F) | −6.5 (20.3) |

−5.9 (21.4) |

−2.2 (28.0) |

3.3 (37.9) |

8.7 (47.7) |

11.6 (52.9) |

13.4 (56.1) |

12.7 (54.9) |

8.5 (47.3) |

3.9 (39.0) |

−0.7 (30.7) |

−5.2 (22.6) |

3.5 (38.3) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −31.6 (−24.9) |

−31.0 (−23.8) |

−23.9 (−11.0) |

−6.1 (21.0) |

−2.2 (28.0) |

−1.7 (28.9) |

4.0 (39.2) |

3.6 (38.5) |

−4.0 (24.8) |

−10.5 (13.1) |

−18.0 (−0.4) |

−27.0 (−16.6) |

−31.6 (−24.9) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 25.6 (1.01) |

29.7 (1.17) |

33.4 (1.31) |

37.9 (1.49) |

61.1 (2.41) |

77.5 (3.05) |

92.3 (3.63) |

70.9 (2.79) |

56.3 (2.22) |

36.8 (1.45) |

33.4 (1.31) |

35.3 (1.39) |

590.2 (23.24) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 1.0 mm) | 7.5 | 8.2 | 7.6 | 7.4 | 9.5 | 10.6 | 11.0 | 8.7 | 7.9 | 7.2 | 7.5 | 8.9 | 102.0 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 85.3 | 83.6 | 79.3 | 70.6 | 68.9 | 73.5 | 74.2 | 74.2 | 78.5 | 81.2 | 86.4 | 87.3 | 78.6 |

| Source 1: World Meteorological Organization[19] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: Climatebase.ru (extremes)[20] | |||||||||||||

Demographics

According to Ukrainian Census (2001), Ternopil city and Ternopil oblast are homogeneously populated by ethnic Ukrainians. Ternopil city and Ternopil oblast are also homogeneously Ukrainian-speaking.[21]

National structure of Ternopil Oblast - 1,138.5 (100%)

- Ukrainians - 1,113.5 (97.8%)

- Russians - 14.2 (1.2%)

- Poles - 3.8 (0.3%)

Native languages in Ternopil:

- Ukrainian language — 94.8 %,

- Russian language — 3.37 %,

- Belarusian language — 0.07 %,

- Polish language — 0.04 %.

According to a survey conducted by the International Republican Institute in April-May 2023, 98 % of the city's population spoke Ukrainian at home, and 1 % spoke Russian.[22]

Economy

.jpg.webp)

Ternopil is a centre for the light industry, food industry, radio-electronic and construction industries. In the Soviet and early post-Soviet period, a harvester plant and a porcelain factory operated in the city.

Transport

Ternopil is an important railway hub with connections to most major railway stations of Ukraine. The city lies on the M12 international highway connecting western and central regions of Ukraine. Trolleybus lines and a bus station are active in the city. Water transport operates on Ternopil artificial lake mostly for tourist purposes. An airport was opened for civilian traffic in 1985, but ceased commercial operations in 2010.

Higher education

Universities include:

Main sights

- Ternopil Regional Art Museum

- Church of the Exaltation of the Cross, Ternopil

- Ukrainian Greek Catholic Cathedral of the Immaculate Conception of The Blessed Virgin Mary

- The sanctuary of Our Lady of Zarvanytsia with a miraculous icon of the 13th century called icon of the Mother of God of Zarvanytsia, sanctuary of Greek-Catholic rite. Located about 40 km from Ternopil, celebrated on 22 July.

Notable people

- Kazimierz Ajdukiewicz (1890–1963), Polish philosopher and logician, researched model theory

- Henryk Baranowski (1943–2013) a Polish theatre, opera and film director, actor, playwright and poet.

- Vasyl Barvinsky (1888–1963) a Ukrainian composer, pianist, conductor and musicologist

- Eugeniusz Baziak (1890–1962) Archbishop of Lviv and apostolic administrator of Kraków.

- Natalia Buchynska (born 1977), singer, brought up in Ternopil.

- Mariia Dilai (born 1980), Ukrainian artist, designer, and social activist

- Daria Chubata (born 1940), Ukrainian physician, author and social activist.

- Mykola Chubatyi (1889-1975),[23] historian of Ukrainian Church.

- Cyryl Czarkowski-Golejewski (1885–1940) aristocratic Polish landowner, Katyn massacre victim.

- Charlotte Eisler (1894-1970) Austrian singer and pianist with the Second Viennese School.

- Kornel Filipowicz (1913–1990) a Polish novelist, poet, screenwriter and short story writer

- Franciszek Kleeberg (1888–1941) a Polish general in the Austro-Hungarian Army

- Bohdan Levkiv (1950–2021) a Ukrainian politician, mayor of Ternopil from 2002 to 2006.

- Pepi Litman (1874–1930) a cross-dressing female Yiddish vaudeville singer

- Kazimierz Michałowski,[6] (1901–1981), Polish archaeologist, Egyptologist and art historian

- Serhiy Nadal (born 1975) a Ukrainian politician; mayor of Ternopil since 2010

- Yuriy Oliynyk (1931–2021) a Ukrainian composer, concert pianist and professor of music in the US

- Jakub Karol Parnas (1884–1949), biochemist, born in Ternopil.

- Joseph Perl,[6] (1773–1839), an Ashkenazi Jewish educator and writer, a scion of the Haskalah

- Simhah Pinsker (1801–1864) a Polish-Jewish scholar and archeologist

- Rudolf Pöch (1870–1921), doctor and anthropologist; pioneer photographer and cinematographer

- Roza Pomerantz-Meltzer (1880–1934) a Polish writer and novelist based in Lviv and politician.

- Solomon Judah Loeb Rapoport (1786–1867), a Galician and Czech rabbi and Jewish scholar.

- Karol Rathaus (1895—1954), Polish-Austrian-American modernist composer

- Eduard Romanyuta (born 1992) a Ukrainian singer, songwriter, actor and TV presenter.

- Baron Lajos Simonyi de Barbács et Vitézvár (1824–1894) a Hungarian politician

- Ruslan Stefanchuk (born 1975) a Ukrainian politician, party chairman and lawyer

- Yaroslav Stetsko (1912–1986), a leader of Organization of Ukrainian Nationalists (OUN) from 1968.

- Oleh Syrotyuk (born 1978) a Ukrainian politician, Governor of Ternopil Oblast in 2014

- Jan Tarnowski (1488-1561), Polish general and nobleman, founder of Ternopil (as Tarnopol).[24]

- Judd L. Teller (1912–1972) Jewish author, social historian and poet; emigrated to the US in 1921.

- Tvorchi, electronic music duo that represented Ukraine in the Eurovision Song Contest 2023.

- Baroness Adelma Vay (1840–1925), a medium and pioneer of spiritualism in Slovenia and Hungary.

Sport

- Olga Babiy (born 1989), a Ukrainian chess player and Woman Grandmaster

- Petr Badlo (born 1976) a Ukrainian football manager and former footballer with 470 club caps.

- Olha Maslivets (born 1978) a Russian windsurfer who competed at four Summer Olympics

- Ihor Semenyna (born 1989) a Ukrainian football midfielder with 330 club caps

People from Ternopil Oblast

- Aleksander Brückner,[6] (1856 in Berezhany – 1939), a Polish scholar of Slavic languages and literature

- Volodymyr Hnatiuk (1871 in Velesniv, Buchach – 1926), Ukrainian writer, literary scholar, journalist and ethnographer.

- Bohdan Lepky (1872-1941), Ukrainian writer, poet and artist.

- Ivan Horbachevsky (1854-1942), Ukrainian chemist and politician active in Austria-Hungary, Minister of Healthcare of Cisleithania.

- Josyf Slipyj (1892-1984), Ukrainian Greek Catholic priest, Metropolitan of Lviv and Halych.

- Solomiya Krushelnytska (1872 in Biliavyntsi — 1952), an outstanding Ukrainian Soprano

- Bohdan Lepky (1872 in Krehulets – 1941), a Ukrainian writer, poet, scholar, public figure, and artist.

- Ivan Pului (1845 in Hrymailiv – 1918) physicist and inventor, developed use of X-rays for medical imaging.

- Casimir Zeglen (1869 near Tarnopol - 1927), Polish-American engineer, inventor of commercial bulletproof vest

- Methodius (Kudriakov) (1949-2015), metropolitan of the Ukrainian Autocephalous Orthodox Church.

- Serhiy Prytula (born 1981 in Zbarazh), Ukrainian TV show host, political activist, founder of Charity Foundation of Serhiy Prytula

Lived in Ternopil

- Sofia Yablonska (1907-1971), Ukrainian-French travel writer, photographer and architect.

- Les Kurbas (1887-1937), Ukrainian theatre director and actor, founder of the first Ukrainian theatre in Ternopil.

International relations

Ternopil is twinned with:

Erftstadt, Germany since 2023 [25]

Erftstadt, Germany since 2023 [25] Sliven, Bulgaria

Sliven, Bulgaria Yonkers, United States (since 1991)[26]

Yonkers, United States (since 1991)[26] Elbląg in Poland (since 1992)[27][28]

Elbląg in Poland (since 1992)[27][28] Chorzów, Poland

Chorzów, Poland Prudentopolis, Brazil

Prudentopolis, Brazil Batumi, Georgia[29]

Batumi, Georgia[29]

Former twin towns include:

Stadium naming controversy

In 2021, Ternopil created international outrage, especially in the Jewish community, by deciding to name a city stadium in honor of Nazi collaborator Roman Shukhevych.[30] Shukhevych was the military leader of the Ukrainian Insurgent Army during World War II and was known for his collaboration with the Nazi regime.[31][32]

Joel Lion, the Israeli Ambassador to Ukraine, expressed Israel’s strong objection to the city's choice to name the stadium in honor of Roman Shukhevych. Lion wrote, "We strongly condemn the decision of Ternopil city council to name the City Stadium after the infamous Hauptman (Captain) of the SS 201st Schutzmannschaft Roman Shukhevych and demand the immediate cancellation of this decision".[32][33]

The Eastern Europe Director of the Simon Wiesenthal Center, Efraim Zuroff wrote, "It is fully understandable that Ternopil seeks to honor those who fought against Soviet Communism, but not those behind the mass murder of innocent fellow citizens." in a statement attempting to convince Ternopil to reconsider the "renaming of its stadium in honor of Nazi collaborator, Hauptmann of the SS Schutzmannschaft 201, Roman Shukhevych, an active participant in the mass murder of Jews and Poles in World War II."[34]

Festivals

An international open-air music festival called Faine Misto has been held annually near Ternopil for 2–4 days in July since 2013.[35][36]

Notes

References

- "Мер Тернополя продає побачення з собою". Ukrayinska Pravda (in Ukrainian). 28 December 2011. Archived from the original on 21 April 2023. Retrieved 6 August 2023.

- Чисельність наявного населення України на 1 січня 2022 [Number of Present Population of Ukraine, as of January 1, 2022] (PDF) (in Ukrainian and English). Kyiv: State Statistics Service of Ukraine. Archived (PDF) from the original on 4 July 2022.

- "Тернопольская городская громада" (in Russian). Портал об'єднаних громад України.

- "Про утворення та ліквідацію районів. Постанова Верховної Ради України № 807-ІХ". Голос України (in Ukrainian). 18 July 2020. Retrieved 3 October 2020.

- "Нові райони: карти + склад" (in Ukrainian). Міністерство розвитку громад та територій України. 17 July 2020.

- Archived 13 October 2015 at the Wayback Machine

- Olszański, Tadeusz A. (2013). "Kresy Zachodnie. Miejsce Galicji Wschodniej i Wołynia w państwie ukraińskim" (PDF). Prace OSW (in Polish). Centre for Eastern Studies. pp. 25–26.

- Karpluk, Maria (1993). Mowa naszych przodków: podstawowe wiadomości z historii języka polskiego do końca XVIII w (in Polish). TMJP. p. 46.

- "Виникнення і розвиток міста Тернопіль" [Establishment and development of the Ternopil city]. ukrssr.com.ua (in Ukrainian). 27 March 2016. Retrieved 8 August 2023.

-

The Jewish and German population accepted the new Ukrainian state, but the Poles started the military campaign against the Ukrainian authority [...] On November 11, 1918 following bloody fighting, the Polish forces captured Lwów. The government of the WUPR moved to Ternopol and from the end of December the Council and the Government of the WUPR were located in Ivano-Frankivsk.

(in Ukrainian) West Ukrainian People's Republic in the "Dovidnyk z istoriï Ukraïny" (A hand-book on the History of Ukraine), 3-Volumes, Kyiv, 1993–1999, ISBN 5-7707-5190-8 (t. 1), ISBN 5-7707-8552-7 (t. 2), ISBN 966-504-237-8 (t. 3). - Robert Kuwałek; Eugeniusz Riadczenko; Adam Dylewski; Justyna Filochowska; Michał Czajka (2015). "Tarnopol". Historia – Społeczność żydowska przed 1989 (in Polish). Virtual Shtetl (Wirtualny Sztetl). pp. 3–4 of 5. Retrieved 31 July 2015.

- Megargee, Geoffrey (2012). Encyclopedia of Camps and Ghettos. Bloomington, Indiana: University of Indiana Press. p. Volume II, 838-389. ISBN 978-0-253-35599-7.

- Frieser, Karl-Heinz; Schmider, Klaus; Schönherr, Klaus; Schreiber, Gerhard; Ungváry, Kristián; Wegner, Bernd (2007). Die Ostfront 1943/44 – Der Krieg im Osten und an den Nebenfronten [The Eastern Front 1943–1944: The War in the East and on the Neighbouring Fronts]. ISBN 978-3-421-06235-2.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - Włodzimierz Borodziej; Ingo Eser; Stanisław Jankowiak; Jerzy Kochanowski; Claudia Kraft; Witold Stankowski; Katrin Steffen (1999). Stanisław Ciesielski (ed.). Przesiedlenie ludności polskiej z Kresów Wschodnich do Polski 1944–1947 [Resettlement of Poles from Kresy 1944–1947] (in Polish). Warsaw: Neriton. pp. 29, 50, 468. ISBN 83-86842-56-3.

- Влада Тернополя наполягає на відновленні військових частин на Західній Україні [Ternopil authorities insist on restoration of military units in western Ukraine]. Ukrainian Independent Information Agency (in Ukrainian). 16 April 2014. Archived from the original on 4 February 2016. Retrieved 4 February 2016.

- "Про утворення та ліквідацію районів. Постанова Верховної Ради України № 807-ІХ". Голос України (in Ukrainian). 18 July 2020. Retrieved 3 October 2020.

- "Нові райони: карти + склад" (in Ukrainian). Міністерство розвитку громад та територій України. 17 July 2020.

- "Ukraine Eurovision act's city Ternopil attacked before performance". BBC News. 13 May 2023. Retrieved 14 May 2023.

- "World Meteorological Organization Climate Normals for 1981–2010". World Meteorological Organization. Archived from the original on 17 July 2021. Retrieved 17 July 2021.

- "Ternopil, Ukraine Climate Data". Climatebase. Retrieved 21 January 2013.

- "2001 | English version | Results | General results of the census | National composition of population". Archived from the original on 17 December 2011.

- "Восьме всеукраїнське муніципальне опитування" (PDF). ratinggroup.ua (in Ukrainian). International Republican Institute. April–May 2023. Archived (PDF) from the original on 19 July 2023. Retrieved 6 August 2023.

- Padokh, Yaroslav (2001). "Chubaty, Mykola". Internet Encyclopedia of Ukraine. Archived from the original on 26 July 2023. Retrieved 9 August 2023.

- Bain, Robert Nisbet (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 26 (11th ed.). pp. 429–430.

- "Städtepartnerschaften". www.erftstadt.de (in German). Archived from the original on 13 May 2023. Retrieved 6 August 2023.

- Hodara, Susan (26 October 2008). "Communities; Cities Find Sisters Abroad". The New York Times. Retrieved 26 October 2008.

- "Elbląg – Podstrony / Miasta partnerskie". Elbląski Dziennik Internetowy (in Polish). Archived from the original on 15 March 2011. Retrieved 1 August 2013.

- "Elbląg – Miasta partnerskie". Elbląg.net (in Polish). Retrieved 1 August 2013.

- "Batumi – Twin Towns & Sister Cities". Batumi City Hall. Archived from the original on 4 May 2012. Retrieved 10 August 2013.

- Piotrowski, Tadeusz (9 January 2007). Poland's Holocaust: Ethnic Strife, Collaboration with Occupying Forces and Genocide in the Second Republic, 1918-1947. McFarland. ISBN 978-0-7864-2913-4.

...on the German side and Roman Shukhevych ('Tur', 'Taras Chuprynka') as head of the Ukrainian staff, wore the uniform of the Wehrmacht.

- "Israeli Envoy in Ukraine Slams Naming of Soccer Stadium in Honor of Nazi Ally Roman Shukhevych", Algemeiner.com, retrieved 22 October 2023

- "Israel protests against western Ukrainian city naming stadium in honor of Shukhevych", Kyiv Post, retrieved 22 October 2023

- "Israel's Ambassador demands cancellation of decision on Ternopil stadium's name", UNIAN, retrieved 22 October 2023

- "FIFA urged to take action after stadium renamed for Nazi collaborator", The Jerusalem Post, 17 March 2021, retrieved 22 October 2023

- "Faine Misto Festival". www.festivalfinder.eu. European Festivals Association. Retrieved 7 April 2021.

- "ФАЙНЕ МІСТО | ТЕРИТОРІЯ ВІЛЬНИХ ЛЮДЕЙ | Історія" (in Ukrainian). Retrieved 7 April 2021.

Sources

- A. Bresler, Joseph Perl, Warsaw, 1879, passim;

- Allg. Zeit. des Jud. 1839, iii. 606;

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Singer, Isidore; et al., eds. (1901–1906). "Tranopol". The Jewish Encyclopedia. New York: Funk & Wagnalls.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Singer, Isidore; et al., eds. (1901–1906). "Tranopol". The Jewish Encyclopedia. New York: Funk & Wagnalls.- J. H. Gurland, Le-Ḳarot ha-Gezerot, p. 22, Odessa, 1892;

- Meyers Konversations-Lexikon

- Orgelbrandt, in Encyklopedia Powszechna, xiv. 409;

External links

- . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 26 (11th ed.). 1911. p. 429.

- Kubijovyč, Volodymyr; Mykolaievych, Roman (2012). "Ternopil". Internet Encyclopedia of Ukraine. Archived from the original on 5 August 2023. Retrieved 10 August 2023.

- (in Ukrainian) Ternopil City Council

- (in Ukrainian and English) Ternopil photos

- Ternopil City Sights

- Website about Ternopil

- Historical footage of war damages at Ternopil (1917), filmportal.de

- Ternopil, Ukraine at JewishGen