Temple of Apollonis

The Temple of Appolonis was built at Cyzicus in mobern Turkey in the 2nd century BC, in order to honor Apollonis of Cyzicus. The Cyzicene epigrams were inscribed in this temple.

Location

Located on the southern Propontis coast of modern-day northwest Turkey, Cyzicus was an important port for the rulers of Pergamon, and friendship was maintained since the beginning of the Attalid dynasty.[1] Founded in the 8th century B.C.E.[2] and retaining its independence throughout the Hellenistic period,[3] it grew to be a center of trade connecting Europe and Asia,[4] comparable in power to the later Byzantium Empire.[5] The city was also a renowned center for education in various fields,[6] with its location allowing for a vast cultural network.

Influence of Apollonis at Cyzicus

With Cyzicus as a major trading hub and potential naval power,[7] the marriage of Apollonis create a strong alliance[8] between her hometown and Pergamon and engendered a stronger form of loyalty by the citizens of Cyzicus through their identification with one of their own. She also imported various aspects of Cyzicus to Pergamon, including iconography styles and political allies, creating a symbiotic exchange of material and cultural trade.[9] Her prestige as an heir-bearing queen would further establish a sense of pride in her hometown, as evidenced by the construction of a temple after her death in which the focus was parent-child mythology. This favourable image of Apollonis by the polis was maintained through royal visits with her sons,[10] to the point they would be invoked in the reliefs of her temple. Her popularity was strong enough that her sons used her name to lay claim to their “origin”[11] at Cyzicus, despite having been born elsewhere, with later generations maintaining the friendship-alliance. She received a dedicated temple, likely near the harbour.

Temple

Following her death and deification in the mid-second century B.C.E.,[12] a temple to Apollonis was built at Cyzicus. It's debated whether the construction was organised by her sons or the polis of Cyzicus;[13] if it was indeed built by her sons, it takes on a characteristically complex motivation.[14] It was allegedly known by simple reference for several centuries afterwards,[15] though its location is lost today.[16] The inclusion of mythology along the theme of child-parent and brotherly love in reliefs at the temple fixed the image of Apollonis and her sons in the collective memory of the Cyzicenes, and throughout the kingdom of Pergamon by way of visitors to the city.[17]

Lack of archaeological evidence

There is no record or decree dedicated to the creation of a temple at Cyzicus to Apollonis. The only evidence of its existence comes from the Palatine Anthology.[18] The book is based on a series of stone epigrams, since lost. No systematic excavations have been done at Cyzicus, much less specifically in search of her temple. The lack of literary or archaeological parallels thus make it difficult to authenticate the limited existing information regarding its existence.

Epigrams of Cyzicus

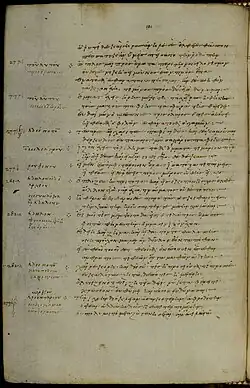

The epigrams are preserved in transcription form in the third book of the Palatine Anthology, compiled in the 10th century AD[19] and later absorbed into the larger Greek Anthology[20] It includes an introduction followed by 19 sequentially numbered epigrams describing the reliefs displayed in the temple, commentary in the margins.[21] The reliefs depict various scenes from Greek mythology[22] connected by a common theme of parent-child devotion and cooperation, oftentimes with two brothers.[23]

The introductory lemma dates the collection to the second century B.C.E, but analysis of the textual style of the epigrams argues that their origin is post-Hellenistic.[24] The textual lemmas (as opposed to the marginal ones) are proposed to have an earlier source than the epigrams,[25] if not a direct source at the temple, as they include autonomous knowledge of the reliefs.[26] The epigrams are hypothesized to be a stylistic experiment by a viewer of the reliefs[27] and when they do offer new details, they do so to emphasize the pathos of the filial piety and its moral and political significance,[28] as well as to display the author's knowledge of ancient culture.[29]

Introductory Lemma

ἐπιγράμματα ἐν Κυζικῷ ἐν τῷ Κυζίκῳ εἰς τὸν ναὸν Ἀπολλωνίδος, τῆς μητρὸς Ἀττάλου καὶ Εὐμένους, Ἐπιγράμματα, ἃ εἰς τὰ στυλοπινάκιον ἐγέγραπτο, περιέχοντα ἀναγλύφους ἱστορίας, ὡς ὑποτέτακται.

[30]Demoen translation: “The epigrams that were inscribed on the stylopinakia in the temple of Apollonis, mother of Attalus and Eumenes at Cyzicus, and that contain stories that were wrought in low relief : they are written below.”

[31]Paton's translation: “In the temple at Cyzicus of Apollonis, the mother of Attalus and Eumenes, inscribed on the tablets of the columns, which contained scenes in relief, as follows : ”

[32]2020 Oxford translation: “At Cyzicus, inside the Temple of Apollonis, mother of Attalus and Eumenes: epigrams which were inscribed on the tablets set into the columns. These tablets contained narrative scenes, carved in low relief, as is set out below.”

The first lemma, the only one deliberately unaccompanied by a poetic epigram, offers important details about the temple (at the cost of confusion over the grammar[33]).[34] It attests to the existence of a temple dedicated to Apollonis at Cyzicus and reinforces her connection to her well-known royal sons;[35] such a fact attests to her lasting fame and importance in the region (however, it does not state her sons built the temple, as is assumed by many scholars[36]). It also states that a series of images based on various myths were carved in relief and displayed there. Finally, it describes some of the architecture in the mention of stylopinakia (στυλοπινάκιον); however, this term is unique to this text and its exact definition and appearance is subject to debate, although it is largely agreed upon to be a pillar or column with some sort of carved display.[37]

The Nineteen Epigrams

For the full text, see volume 1 of the Greek Anthology translated by W.R.Paton[31]

Iconography

The reliefs at the temple were “ephemeral”[38] carvings, likely bas-relief,[39] as is seen in the style of other reliefs at Cyzicus at the time. The location of the reliefs themselves within the temple are argued to either be between each pillar or directly on them, whether permanent or detachable.

The subject matter ranges from widely-known to obscure,[40] with all depicting mythology sourced from various places in the Hellenistic Greek world,[41] establishing a pan-Mediterranean connection. Each image is related to the theme of filial piety and brotherly cooperation, ranging from violent to peaceful in seemingly random order.[42] The violence described in some of the scenes would require dramatic and dynamic renderings to remain accurate to the descriptions.[43]

The reasoning behind the myths chosen are the subject of debate; some argue that the rarity or disparity of connection between some of the stories and the Attalids or Apollonis herself reflects poorly on the themes of motherhood and brotherhood, but this ignores the fact that it is unknown which would have been popular in Cyzicus specifically, or the political implications of including certain mythical figures. It is likely if the reliefs were truly as described, the variants chosen were due to the careful deliberation of scholars or religious officials close to the Attalids,[44] and with knowledge of the cultural network of visitors to Cyzicus. Certain epigrams also allude directly to stories associated with Apollonis in life[45] and/or famous Pergamon monuments to mothers.[46]

Architecture, location, and other spatial information

With the lack of archaeological verification, the structure and verbiage of the collection of epigrams offer the only insight into the layout of the temple. This introduces the problem of emission; details difficult to incorporate may be the fault of the source leaving out design aspects they thought irrelevant (ex. extra columns that had no associated reliefs or decorations unrelated to the theme of filial piety).

The lemmata offer precise indications of the cardinal directions[47] (as well as a sense of movement through specific diction choices[48]), with the front of the temple agreed upon by most scholars to be facing south.

The stylopinaka are known to be arranged in a continuous sequence[49] along the peristyle, with one per epigram, but the uneven number listed complicates renderings of their placement[50] (see figs. 6-8). Controversy is further invoked in defining the appearance of the stylopinakia themselves, due to the translation difficulties; the main debate[51] is whether the reliefs were inscribed onto the pillars themselves, on the walls between, or on a separate tablet that was then attached to the pillar.

An additional difficulty is determining the material of the columns and the reliefs. Whilst the reliefs are agreed to be carved in bas-relief, the word used can refer to stone, marble, clay or even metal through embossing or chiseling.[52]

References

- OGIS 748 : Philetairos is recorded to have given donations to the city between 280-275B.C.E., including military aid, tax privileges, and oil to be used in athletic competitions and received a festival in thanks (the Philetaireia) (Dana 2014:206-8). C.f. Zanon 2009, Hasluck 1910 & Hansen 1971.

- Founded by Ionian Greek colonists and city-states, those new cities in the Delian League would retain their Greek characteristics despite the presence of the native Asia Minor culture, to the point that the “use of Greek as the primary language was never displaced” (Kearsley 2005:102).

- Kassab Tezgör, Dominique (2015). "Review of: Cyzique, cité majeure et méconnue de la Propontide antique (coll. Centre de recherche universitaire lorrain d'histoire, 51) by Michel Sève, Patrice Schlosser". Revue Archéologique. 2: 406–408 – via JSTOR.

- Dana, Madalina (2014). "Cyzique, une cité au carrefour des réseaux culturels du monde grec". In Sève, Michel; Schlosser, Patrice (eds.). Cyzique, cité majeure et méconnue de la Propontide antique. Metz: Centre de Recherche Universitaire Lorrain d'Histoire. pp. 151–165.

- Sève, Michel; Schlosser, Patrice, eds. (2014). Cyzique, cité majeure et méconnue de la Propontide Antique. Metz: Centre de Recherche Universitaire Lorrain d'Histoire. p. 116.

- Dana 2014 illustrates the vastness of Cyzicus’ contributions to ancient knowledge, with its emergence as a center of mathematics even before Alexandria, the movement of historians and philosophers between Cyzicus and Athens, and a long tradition of novel architecture, which may have been imported into the Pergamonian style through Apollonis’ connections (see note 19).

- Such an aspect came into play during the rule of Eumenes II and Attalus II, in which Cyzicus provided a large quantity of warships and aide (Van Looy 1976:152 ; Polyb. 25.2.13, 33.13.1). Such an action also prevented the need of Pergamon to rely on paid mercenaries during these conflicts, with strong patriotism amongst the Cyzicenes equalling greater willingness and effort to fight (Fehr 1997:57).

- At the time of the marriage, Attalus I was still in the midst of establishing Pergamon as a kingdom able to compete with the Macedonians and Seleukids; this involved the issue of political legitimacy, territorial expansion, and winning the support of other cities in Asia Minor. Cyzicus, with its prime location at the mouth of the Black Sea, offered a strategic alliance with a foundation of friendship already set by his ancestor (Mirón 2020:212).

- Apollonis thus symbolized not only familial unity, but the unity of the empire as well. Carney 2011:208 writes of ancient queens: “We need to recognize them as dynastic go-betweens with enduring ties to the oikos of their birth.”

- Polyb. 22.20 recounts her visit to Cyzicus with two of her sons (Attalus and one other not mentioned by name) after the war against Prussia (184 B.C.E.), in which Cyzicus provided a quarter of the naval ships (twenty out of eighty total; Hasluck 1910:177). He states that she toured the city and its temples and was supported by her sons, who placed her between them and held her hands. He notes that the Cyzicenes applauded this sign of respect and affection of the sons towards their mother, one of their most distinguished citizens, comparing them to the mythical brothers Cleobis and Biton helping their mother up the stairs to the temple of Hera. This myth was one of the reliefs included at the Temple of Apollonis at Cyzicus. Such a visit likely also reflects Apollonis’ nostalgia and strong emotional connection to her birthplace, and her desire to thank them for their help. Both the visit and the subsequent relief were very likely carefully orchestrated political acts reflecting true emotional attachments.

- Strabo 14.1.6; In a letter to the Ionian League, Eumenes II mentions his connection with the Milesians through Cyzicus, i.e. through his mother (OGIS 763, l. 65; RC 52).

- The lack of an exact date of death results in a large range of possible dates of building the temple, which remains debated. Hansen 1971:100 puts it after 184/183 B.C.E., Van Looy 1976:161 and Looy-Demoen 1986:134 put it between 175 and 159 B.C.E., and Massa-Pairault 1981-1982:182-4 thinks 172 B.C. to coincide with the false death of Eumenes II.

- Polybius 22.20 is cited by Mirón 2018b and Zanon 2009 as stating that Attalus II and his brother built the temple, but there's no actual mention in the text beyond her visit whilst alive. The Cleobis and Biton myth connect the visit in Apollonis’ life with the reliefs in her temple, but this could have easily been an aspect a city official noticed and thus included, considering its apparent popularity. The surviving epigrams of the temple offer no information regarding its commissioning patron/provenance, simply dedicating it to “Apollonis, mother of Attalus and Eumenes,” rather than “Attalus and Eumenes built this for their mother” or something to that effect. Sève 2014:160-1, rejects either a funerary or dynastic cult for Apollonis at Cyzicus, stating that the construction of a temple by the royal family of Pergamon would not be appropriate in an independent city-state. He concludes that if a temple was indeed constructed, it would be due to the polis of Cyzicus deciding on doing so, as an act of gratefulness to the Attalids and to honour one of their own citizens, thus making it a civic cult. Ballestrazzi 2017 hypothesizes that the inclusion of the names is an artificial inclusion by a later writer, due to the memory of Apollonis and her sons having faded. It is also possible the temple and its inscriptions were indirectly built on behalf of the brothers, as Livingstone & Nisbet 2008 believe.

- In creating a temple for their mother at her birthplace, her sons would cement their own power and connection to the area, as well as a favourable reputation amongst its people. The sons regularly used the figure of their mother to highlight their commitment to family and “democratic” (Van Looy 1976:151) virtues and ideals, a mission Apollonis herself endorsed and cooperated to create, whilst also having a true attachment to and respect for their mother as a figure of authority in their lives (Mirón 2018a). One side to the motivation was to benefit their own reputation as sons, as a site of public propaganda; another is the likelihood of its attraction as a type of ancient “tourist” site; still one more is a genuine desire to preserve the memory of their mother and their relationship in a place important to her.

- This recognition is based on its inclusion in the Palatine Anthology of the 10th century.

- Hasluck 1910:177 theorized that it was near the “north-west corner of the central harbour, where there are ruins (De Rustafjaell marks "Temple"?),” upon the basis of her Teos epithet “apobateria.” Ruins were found in that location; however, Hansen 1971:289 argues against it being the Temple of Apollonis, on account that the ruins face east or west, and the Temple of Apollonis has largely been agreed up to face south.

- The temple cemented the link of Cyzicus with the Attalids through Apollonis; thus, the temple became a “place of memory of the queen mother, as well as an affirmation of loyal relations both within the royal family and between Cyzicus and Pergamon. The expression of these ideas through an architectural monument commemorated the importance they had for the Attalids, and of their intention for these relations to last through the generations. [...] Beyond this, the orderly and complex iconographic program of the temple, which included myths from around the Greek world, seemed to connect the free Greek cities with the monarchy of Pergamon, embodied by the mother. In this sense, Apollonis not only linked the Attalids with Cyzicus, but also, through mythic and real kinships, with all the Greek cities, especially Ionian ones, since Cyzicus was a colony of Miletus.” (Mirón 2018a:25).

- Such a lack of evidence causes controversy amongst scholars as to whether the information is not a fictional exercise of an ancient storyteller. Certain elements are too specific to have been anything but someone citing an existing structure, which will be covered in section Architecture, Location, and Other Spatial Information. Ballestrazzi 2017:129 admits their doubts, but also supports the idea that it's probable that some sort of monument to Apollonis was indeed constructed in her hometown, considering her status as an important symbol in propaganda and the number of post-death cults and statuary dedicated to her.

- Such a date further undermines the reliability of the text, considering the large gap in time between Apollonis’ death and the transcription date.

- This edition was found in 1606, located at the Palatine Library in Heidelberg, based on the now-lost 10th century collection of Constantinus Cephalas.

- Each has two parts: the lemma (“heading”) describing the relief image in prose in lieu of an actual illustration, and an accompanying prose-poem (the epigram itself). The 17th epigram is nearly completely lost, with only the lemma and a few words from the poem surviving due to damage on the original stone.

- With the exception of the final relief, which illustrates the Roman myth of Romus and Remulus. This is likely due to the Attalids’ strong alliance with the Romans, possibly as a form of flattery directed at Roman visitors or immigrants to the city. It may also be the invention of a later writer as a means to justify the conquest of Asia Minor by the Roman Empire, by implying them as the natural cultural inheritor of the Hellenistic Greeks through dutiful sons (Livingstone & Nisbet 2008).

- Ballestrazzi 2017:136 describes this as “pietas erga parentes.” These include, but are not limited to: a mother being saved from rape, emprisonment, being killed, avenging her death, or guiding her to happiness in the afterlife. A notable exception to the iconography of brothers is Apollo and Artemis in two separate reliefs and their description in the related lemmas; however, the epigram only describes Apollo.

- Meter, tenses, vocabulary, sentence structure, conjugation, etc.; for support of a later date, see in particular Meyer 1911 and Demoen 1988 (who dates it to the 6th century AD or later), as well as Ballestrazzi 2017. Maltomini 2002 argues successfully against it being a construction by the compilers of the Palatine Anthology, which puts the latest date possible as the 10th century AD. Some, however, argue its having an earlier date than Demoen's proposition, notably Massa-Pairault in 1981-82; Merkelbach and Stauber 2001 also accept it as a direct transcript from the temple. Kuttner 1995:168 thinks there were epigrams at the temple but those are not the ones in the anthology. I propose three other hypotheses here: it is possible that the lemma themselves are direct quotations of inscriptions created soon after the building of the temple, acting as an ancient form of travel brochure or even souvenir, made in response to the apparent popularity of Apollonis in combination with the prime location in Asia Minor, with the epigrams the creative invention of a later scribe. It is also possible they are based on texts inscribed at the temple, suffering from a “telephone-game” effect, in which it is a copy of a copy based on an oral transfer, thus creating unintentional changes that would put it at a later date as language changes over time (Ballestrazzi 2017 suggests such a chain of sources). Considering the dates proposed by Demoen and the commentary of Ballestrazzi 2017, as well as the presence of pagan iconoclasm in the Roman Empire in the 4th century AD and Christian iconoclasm in the nearby Byzantine Empire in the 8th century AD, another theory is that the temple was deliberately destroyed around this time and the confusing grammar is due to someone hurriedly copying or recalling the information in an effort to preserve it. However, these hypotheses are unable to be proven by myself at this time.

- See Maltomini 2002 ; Ballestrazzi 2017 joins with Maltomini to argue against the idea that the lemmas were later added by the compilers of the Palatine Anthology.

- This is best seen in the seventeenth epigram, in which the lemma describes the relief despite the absence of the epigram. Other examples include the inclusion of Artemis in two of the lemmas but not in their respective epigrams, as well as in the first lemma in which several side characters are mentioned in the lemma but not the epigram. The 12th is unique, in that it describes a myth that does not have a record elsewhere, and yet also has nothing in the epigram that isn't already described by the lemma.

- See Farnell 1890, Demoen 1988, Maltomini 2002 & Ballestrazzi 2017.

- This is seen in the 18th epigram, detailing the myth of Cleobis and Biton. The epigram appropriately stresses the love and reverence of the sons towards their mother, simultaneously alluding to the collective memory at Cyzicus of the famous visit by Apollonis and her sons, as well as encouraging such loyal behaviour towards their own parents, ancestors, and by extension, the authorities at Pergamon.

- Ballestrazzi 2017:152 claims of the unknown author: “Egli volle corredare le sue scene mitologiche di scadenti versi impregnati di erudizione classica, spinto forse non tanto dalle virtù della regina cizicena e dei suoi figli quanto dal fascino del mito e della letteratura del passato.”

- Demoen, Kristoffel (1988). "The Date Of The Cyzicene Epigrams. An Analysis Of The Vocabulary And Metrical Technique Of AP, III". L'Antiquité Classique. 57: 231–248. doi:10.3406/antiq.1988.2236. JSTOR 41658027 – via JSTOR.

- The Greek Anthology: Volume 1. Translated by Paton, William Roger. London, New York: W. Heinemann, G.P. Putnam's Sons. 1916–18. p. 95.

- Nisbet, Gideon, ed. (2020). Epigrams from the Greek Anthology. Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 16.

- The omission of certain details like location alongside the poor grammar could be explained by the idea that the source or inspiration for the epigrams were a form of ancient tour guide. For example, contemporary guidebooks today don't include the mailing address of the Acropolis at Athens, on the assumption that people will already know the location or find a local to guide them there, and poor translations by locals in tourism ads still exist. Boissonade in Dübner 1864:45 suggests the existence of such a guide sold to visitors of the temple, with their conclusion later reinterpreted to mean such a guide containing the lemma. Radinger 1897:122 speculates that both the lemma and epigrams were inspired by another source describing the temple. See note 114 for the “telephone-game” theory.

- As a single sentence, any grammar errors make for an unreliable or difficult translation. One example is that in regards to the stylopinakia, Livingstone & Nisbet 2008 complain about the misuse of εἰς (into or to) to mean “on” in regards to the reliefs on the columns, whilst Ballestrazzi 2017:138 argues that εἰς is instead being used to specify the subject of the collection of epigrams, as is found elsewhere in the Palatine Anthology, and that this makes the translation closer to “inscribed epigrams concerning the temple of Apollonis” rather than “epigrams inscribed on the columns at the temple,” a conclusion agreed upon by Froning 1981:41.

- At the same time, it is noticeable that there is a lack of honorific titles for all three, and that her remaining sons are not mentioned; Van Looy & Demoen 1986 concluded from this that it is not a transcript of an on-site dedication or dedication by these two sons specifically, but rather a reconstruction by the author of Apollonis’ importance based on her connection to two rulers of Pergamon that would be commonly known to their audience.

- Ballestrazzi, Chiara (January 2017). "Gli Stylopinakia e il tempio della regina Apollonide di Cizico. Una revisione letteraria e archeologica del terzo libro dell'Anthologia Palatina". Rivista di Filologia e di Istruzione Classica. 145 (1): 130. doi:10.1484/j.rfic.5.123424. ISSN 0035-6220.

- See note 120; cf. Herman Van Looy and Kristoffel Demoen, Le temple en l'honneur de la reine Apollonis à Cyzique et l'énigme des stylopinakia, in Epigraphica Anatolica, 8 (1986):133-142.

- This is on account of a temporal conjugation in the introductory lemma, leading to confusion over the material considering most reliefs were carved into stone; some have concluded it refers to removable tablets, which could be brought in and out of the temple whenever needed. Ballestrazzi 2017:152 writes: “Forse esposti solo in occasione di qualche ricorrenza o festa collegata al culto di Apollonide112, un loro statuto mobile e parzialmente effimero spiegherebbe la difficoltà di inserire gli stylopinakia all’interno degli elementi architettonici tradizionali e la totale mancanza di paralleli.”

- This refers to a deep carving, in which figures seem to protrude outwards, with the background receding, to create depth. This is characteristic of reliefs at Pergamon as well, such as in the Gigantomachy frieze at the Great Altar. The stylistic similarities of bas-relief sculpture at Cyzicus and Pergamon cannot be ignored; it is likely they mutually influenced the development of the other, and likely imported sculptors between the cities. It is therefore easy to imagine the lost reliefs at the Temple of Apollonis to have an artistic style similar to the well-preserved examples at the temples of Pergamon, as well as various smaller monuments made in Cyzicus at the time of Apollonis’ death. Farnell 1890:194 proposes the idea that the reliefs at Cyzicus may even have been carved by those working on some of the smaller temple friezes at Pergamon, but this has not received discussion by modern historians.

- i.e. two (6 & 14) dedicated to the famous Olympian twins Apollo and Artemis (whose organisation in the later lemma reminded Farnell 1890 of the Pergamene frieze of Apollo with a fallen giant at his feet) vs Megapenthes threatening Bellerophon (15) which is a role not depicted elsewhere of this character.

- Neumer-Pfau 1982 has argued that the myths chosen for Pergamon-oriented monuments reflect the cultural melting pot of Asia Minor, the Hellenistic Greek world, and their Roman connections, and that this range would allow various ethnic groups to identify at least one familiar story in regards to divine mothers, particularly considering Asia Minor's indigenous matrilinear belief systems and the rising importance of Rome in the Mediterranean (and by extension, their growing preference for a classic “Roman matron” type). This is alluded to by Ballestrazzi 2017:137, who mentions that the vagueness in the description would be acceptable to readers already familiar with the iconography and decorative elements, perhaps because they had already visited it. The blending of cultures would result in an “international” symbol of cooperation and unity, as represented by the “Hesiodic” idea of family harmony, updated via the introduction of the mother as a binding force. See Fehr 1997, Mirón 2020.

- It is noteworthy to mention that on the southern stylopinakia, the reliefs in the popular 4x7 layout of the temple would all be famous pairs of brothers, which is in line with the visit of Apollonis and her sons.

- i.e. the moving petrification of limbs, the running of a bull, pained agony, blood rushing out, the melting of flesh due to fire, etc.; some of these artistic practices may have a precedent or origin at the Pergamon friezes. See Farnell 1890.

- Maltomini, Francesca (2002). "Osservazioni Sugli Epigrammi Di Cizico ("AP" III)". Annali della Scuola Normale Superiore di Pisa. Classe di Lettere e Filosofia. Serie IV: 7, no. 1: 17–33.

- The eighteenth epigram details the myth of Cleobis and Biton famously associated with Apollonis and her sons at Cyzicus (see notes 102, 119). Cleobis and Biton's leading their mother to a temple to Hera may thus explain why Apollonis was entombed at the temple to Hera established by her son at Pergamon, rather than at her sanctuary, where other Attalid dynastic mothers like Boas were buried, or near the unknown location of her husband's tomb. Massa-Pairault 1981-2:182-6 has also proposed that Apollonis was alive for the false news of her eldest son's death and that the eighth epigram, in which a son meets with his mother in the Underworld, is a reference to Apollonis having died from grief. Mirón 2018b:166 has proposed an alternate interpretation of this, in that upon Eumenes’ death, Apollonis would act as a guiding force in maintaining respectability and the expected harmony of the royal family.

- The figures/myths depicted in the first and second epigrams (i.e. the mother figures of Semele and Auge) are also found at the Great Altar of Pergamon; Apollonis is thought to have been connected to Auge at Pergamon (see note 74). Fehr 1997:54 also notes that the monumental Dirce group in Naples also depicts the brothers Amphion and Zethus avenging their mother, as in the seventh epigram; this depiction also has similarities in the Farnese group of Pergamon, which has no precedent in the area and may have originated with that artistic school.

- The relative exactness of the cardinal directions, compared to the vagueness or contradictory elements in the rest of the epigrams, supports the idea that the description is based on a real building, providing a basis of reliability for the source (although there are some inconsistencies in even this aspect that prevent agreement on the floorplan, in regards to the tenth lemma).

- Ballestrazzi, Chiara (January 2017). "Gli Stylopinakia e il tempio della regina Apollonide di Cizico. Una revisione letteraria e archeologica del terzo libro dell'Anthologia Palatina". Rivista di Filologia e di Istruzione Classica. 145 (1): 141–48. doi:10.1484/j.rfic.5.123424. ISSN 0035-6220.

- Livingstone, Niall; Nisbet, Gideon (2008). "III Epigram from Greece to Rome". New Surveys in the Classics. 38: 99–117. doi:10.1017/s0017383509990210. ISSN 0533-2451. S2CID 164260744.

- It is possible the one of the compositions is an artificial addition by a later scribe, or that an epigram detailing a 20th relief is lost (Maltomini 2002:25); of the two, the latter is thought to be more plausible. Several proposals of such a plan are given: a peripteral of 6x6, peripteral of 4x8, 4x6 with two stylopinakia on the corner columns, etc.

- Van Looy & Demoen 1986 propose the stylopinakia refers to reliefs independent of the columns; Demoen 1988 furthers this argument with the idea that the word indicates that only an epigram or inscription was on the columns, rather than the reliefs, and that the reliefs were on separate, detachable tablets, i.e. “tablet of a column.” The LSJ Lexicon translates it as “pillars with figures on them.” Paton used “tablets of the columns.” Maltomini 2002 also believes the reliefs were not on the columns. However, Hansen 1971:289 supports the idea that the iconographic reliefs were either on the lower drums of the columns or the wall between them. Ballestrazzi 2017:146 is open to the idea of reliefs on the column bases, metopes in a frieze, or ephemeral tablets, so long as the stylopinakia themselves form a Π inside the cella. Schober 1951:119-20, in establishing a layout of 6x6 stylopinakia, also supports this intercolumn setting, with five reliefs on each side except the south to allow an empty space for an entrance. Massa-Pairault 1982 proposed that the stylopinakia were entirely separate from the columns and instead inside the cella, erasing the necessity of symmetry entirely.

- See Ballestrazzi 2017, Froning 1981; it is largely assumed to be stone (likely marble), on account of its accessibility and experience with it by carvers at Cyzicus. However, some argue that the “ephemerality” does not refer to its transportability, but in being perishable material itself; suggestions include wood, cloth, or paper-mache, referring to the decoration of churches.