Tequixquiac

Tequixquiac is a municipality located in the Zumpango Region of the State of Mexico in Mexico. The municipality is located 84 kilometres (52 mi) north of Mexico City within the valley that connects the Valley of Mexico with the Mezquital Valley. The name comes from Nahuatl and means "place of tequesquite waters".[1] The municipal seat is the town of Santiago Tequixquiac, although both the town and municipality are commonly referred to as simply "Tequixquiac".

Tequixquiac | |

|---|---|

Municipality | |

Church of Saint James Apostle in Tequixquiac | |

Flag  Seal | |

| |

| Coordinates: 19°54′34″N 99°08′41″W | |

| Country | |

| State | State of Mexico |

| Region | Zumpango Region |

| Municipal seat | Santiago Tequixquiac |

| Founded | 1168 |

| Municipal Status | 1820 |

| Government | |

| • Municipal President | Gilberto Ramírez Domínguez |

| Elevation (of seat) | 2,200 m (7,200 ft) |

| Population (2010) | |

| • Municipality | 33,907 |

| • Seat | 20,610 |

| Time zone | UTC-6 (Central (US Central)) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC-5 (Central) |

| Postal code (of seat) | 55650 |

| Website | (in Spanish) http://www.tequixquiac.gob.mx/ |

The municipality is known as the "cradle of prehistoric art in the Americas" because of the sacrum bone and other artifacts found in the region.[2]

History

The sacrum bone found in Tequixquiac is considered a work of prehistoric art. The first indigenous settlers of Tequixquiac were the Aztecs and Otomi, who settled permanently due to the abundance of rivers and springs. They were engaged mainly in agriculture and the breeding of domestic animals.

In 1152, the Aztecs, on their way from Tula-Xicocotitlan to Tequixquiac and the Valley of Mexico, decided to settle for a short time at a place called Tepetongo. This land was named Teotlalpan by Tepanecs tribe.

In 1168, the village of Tequixquiac was founded, which had approximately 250 houses scattered the length and breadth of the nearby hills. Tequixquiac village was conquered by the Aztecs under the rule of Emperor Chimalpopoca.

During colonization after the fall of Tenochtitlan, Hernán Cortés rewarded his soldiers with parcels of land. One of them was Tequixquiac, which was given to two Spaniards: Martín López, builder of the brigantines used in taking Tenochtitlan, and Andrés Núñez. López and Núñez split the parcel in two, and their children inherited it after their death. Tequixquiac belonged to the Zitlatepec corregimiento. At this time the Viceroy Luís de Velasco made regulations on the Encomienda system, mandating the protection of indigenous people.

In the territory of Tequixquiac, the Apaxco and Hueypoxtla regions had deposits of limestone. Grants awarded to the Spanish introduced a thriving industry using indigenous labor, decimating the population in conditions of extreme poverty and forced labor.

By 1552, families dispersed by a Tlaxcaltec named Francisco Lopez de Tlaltzintlale were gathered and stripped of their land; these possessions were distributed through royal grants to Spaniards, some was Marranos or New Christians (Sephardic settlement converted to Roman Catholic religion).

The Spanish Empire sought to justify their acts through the Christian missions. The Franciscans arrived in New Spain in 1524, but clerics arrived even before that to proselytize to the natives, building a chapel in each encomienda.

With the help of the Franciscan friars, the temple of Saint James the Apostle was built, raising Tequixquiac from the rank of vicarage to parish. The Church of Santiago Tequixquiac became a parish in 1590. The construction of the building was carried out in different stages. The parish is a large atrium space with a cross of carved stone in the center. Indigenous and Christian symbols adorn the four corner chapels in the pits. There is an open chapel with columns on the facade and two stone jambs built by Native Americans and carved with work from their philosophical perspective. The temple was dedicated to Santiago Apóstol, because some families from Galicia, Asturias, Andalusia, and Leon were in the region.

At the beginning of the political jurisdiction, Tequixquiac covered the current territory of Tlapanaloya without the people to be integrated into the eighteenth century. The independence movement spread to Tequixquiac through the medium of dances and arrieria. Tequixquiac was among the first municipalities constituted in the province, on November 29, 1820, by joining the Mexican War of Independence on the basis of the Cadiz Constitution.

Bando Municipal for the December 17, 1823, he published Tequixquiac the form of government that would govern the country. 'Mexican nation adopts for its government as representative of People's Federal Republic,' published in the same way the oath to the Constitution of the United Mexican States in October 1824.

By Decree No. 41 of April 8, 1825, was added to Zumpango: Hueypoxtla and Tequixquiac belonging andalusia Tetepango party, based on the law at the same time, the prefect of Tula and separates Tequixquiac haciendas de Tena and corners of the municipality of Guadalupe Atitalaquia.

.JPG.webp)

The Grand Canal was built through Tequixquiac during the presidency of Porfirio Díaz in order the drain the Valley of Mexico. It was the second phase of construction by British company Mexican Prospecting and Finance Co Ltd. y la Read & Campbell in 1867,[3] the workers stayed in encampments around the Hacienda of Acatlan in El Tajo de Tequixquiac.[4] During its construction many archeological finds were uncovered of early existence of humans in this area. One of the engineers of the canal project, Tito Rosas, is credited with finding the "Sacro de Tequixquiac".

During the Mexican Revolution, General Emiliano Zapata arrived to Tequixquiac and redistributed the lands of the municipality. Approximately 275 hectares of land was redistributed under the ejido system. Another 3,338 hectares was awarded as ejido land by President Emilio Portes Gil. A system to irrigate these lands was sponsored by President Lázaro Cárdenas between 1937 and 1938, installing a pump to take water out of the drainage canal to irrigate lands here.[1]

.jpg.webp)

Another drainage canal for the Valley of Mexico was built through here in 1954 under the presidency of Adolfo Ruiz Cortines. This spurred economic development of the municipality by increasing the amount of cultivable land. The construction of a highway connecting the municipality to Zumpango, Apaxco and the state of Hidalgo helped it to reach new markets.[1]

Geography

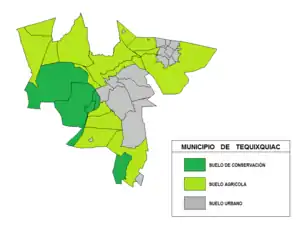

The municipality is located in the northern part of the State of Mexico.[5]

The town of Santiago Tequixquiac, the municipal seat, has governing jurisdiction over the following communities: La Heredad, San Miguel, Tlapanaloya, El Cenicero, Colonia Wenceslao Labra, Colonia La Esperanza, Palo Grande, Monte Alto, El Crucero, La Arenilla, La Rinconada and La Vega.[6] The municipality has a total area of 96.37 square kilometres (37.21 sq mi) and borders the municipalities of Apaxco, Hueypoxtla, Zumpango, Huehuetoca and the state of Hidalgo.

The Gran Canal de Desagüe (known as the Xothé River in the Otomi language) is an artificial channel which crosses Tequixquiac. This channel connects with the Tula river and Enthó dam. Other small rivers which connect with Gran Canal are the Río Salado of Hueypoxtla, the Treviño river, and the La Pila river.[5]

The municipal seat is located in a small, narrow valley, but most of the municipality is on a high mesa between the Valley of Mexico and the Mezquital Valley.[1] The highest mountain in Tequixquiac is the Cerro Mesa Ahumada, with an elevation of 2,600 metres (8,500 ft) above sea level,[7] on the border between the municipalities of Huehuetoca and Apaxco.

Flora and fauna

There is a diversity in plants and animals of temperate climate (Mexico Valley) and semi-arid climate (Mezquital Valley).[8]

Plants native to the municipality include:

- maguey (agave americana)

- cardón or cholla (cylindropuntia imbricata)

- nopal or prickly pear (opuntia ficus-indica)

- viznaga or golden barrel (echinocactus)

- órgano or fencepost cactus (pachycereus marginatus)

- garambullo or billberry cactus (myrtillocactus geometrizans)

- palo dulce (eysenhardtia polystachya)

- mesquite (prosopis juliflora)

- ahuehuete (taxodium mucronatum)

- encino or netleaf oak (quercus rugosa)

- tepozán (buddleja cordata)

- huizache (vachellia farnesiana)

- cedro or white cedar (cupressus lusitanica)

- sause or willow (salix)

- xaixne or creosote bush (larrea tridentata)

- dingandán or pepicha (porophyllum linaria)

- depe or creeping false holly (Jaltomata procumbens)

- tule (schoenoplectus acutus)

- carrizo (phragmites communis)

- tejocote (crataegus mexicana)

- capulin (prunus serotina)

- white sapote (casimiroa edulis)

Native animals include: cacomistle, skunk, gopher, Virginia opossum, rabbit, Mexican gray squirrel, turkey, colibri, turkey vulture, northern mockingbird, rattlesnake, pine snake, xincoyote (Sceloporus spinosus), red warbler, rufous-crowned sparrow, lesser roadrunner, great horned owl, axolotl, frog, toad, red ant, bee, and others.

In prehistoric times, the area was populated by large mammals such as glyptodonts, mammoths, horses, and bison.[9]

Ecology and environment

Tequixquiac is one of the State of Mexico's municipalities with a low environmental impact. Its people have denied any proposed municipal plan for urban development.[10] The town has a large pool of rain water catchment for the Valley of Mexico, the soil is not contaminated by industry.

The people have an attachment to the land and the natural environment. As a semi-rural municipality in proximity to the Mexico City metropolis, Cerro Mesa Ahumada is a well-preserved natural area with many species of flora and fauna that are no longer possible to see in neighboring municipalities.[11]

In addition, Tequixquiac is one of the metropolitan municipalities of Mexico City where the environmental footprint is moderate. The impact of industrial and urban activities is lower than in other municipalities in the state. However, a major environmental problem that residents face is over the Tequixquiac Tunnel, opened during the government of former president Porfirio Díaz. The tunnel has been a locus of infection and waste gases given off by sewage from residential, commercial, industrial, and hospital areas of Mexico City.

Tequixquiac Tunnel causes debate among the locals, the Comición Nacional del Agua (National Water Commission), and different levels of government. Continuing to build the extension of the tunnel on the Gran Canal would bring a million-dollar water project to the area. Wastewater is used to support agriculture, and the land filters the water as it is decanted into the ground. The water also contributes to a number of underground streams vital to the ecological balance of the area. Restricting the water supply for agricultural use would increase land speculation and force ejidatarios to sell their land for housing development. This would leave a great ecological impact on the country, since this region and others in the Midwest serve as buffer areas for rain water filtration, buffer zones between Mexico City and less urbanized land, and regulators for the temperature of the Valley of Mexico.

Communication and transport

.jpg.webp)

Many paths and road in Teotlalpan had been built by the Aztec people to control the area, including an old road connecting the mythic Tula Xicocotlán with Texcoco Valley, crossing Tequixquiac. During the Spanish conquest and colonial period, this road was used for merchant traffic including freight of stone, silver, gold, lime, fruits, corn, wood, wine and furnitures. The Spanish built the camino real (English: royal road) from Tepotzotlán to Actopan, connecting with Camino Real de Tierra Adentro, crossing by Coyotepec, Huehuetoca, Tequixquiac, Tlapanaloya, Hueypoxtla, Apaxco, Santa Maria Ajoloapan, Ajacuba, Tezontlale, Ixcuincuilapilco, San Agustín, Tecama, Tepenene and Chicabasco. This Camino Real was connected with others ways named; Camino Real to Tizatuca and Camino Real of San Sebastian Buenavista to Zumpango.

After independence, the first works for the Gran Canal de la Ciudad de México (English: Grand Canal of Mexico City) were started; an English company, Read & Campbell Company, won the contract. The Mexican government with an English company built a railroad from Progreso de Obregón to Tequixquiac to transport workers, tools, material, light energy and merchant products to Mexico City from Progreso de Obregón, Apaxco and Tequixquiac. The first railroad was destroyed during the Mexican Revolution, but other railroad lines to Querétaro City and Mexico City were built.

Two state roads cross through the municipality, linking it with Zumpango–Apaxco number 9, which connects with Mexico City and Atitalaquia in State of Hidalgo. Other municipal roads connect with Tlapanaloya, Hueypoxtla and Arco Norte highway. Another road, Huehuetoca-Apaxco number 6, connects to the Tula–Jorobas highway.

Three rail lines pass through, linking to Mexico City, Pachuca and Querétaro. There is no main bus station. The principal destinations are Indios Verdes, Martín Carrera and Cuatro Caminos subway stations in Mexico City, for public transport to Hueypoxtla, Zumpango and Apaxco. Other destinations are Ecatepec de Morelos, Tlahuelilpan Main bus station, International Airport of Mexico City, and Tepotzotlán Main bus station. Two routes connect to the state capital, Metro Observatorio bus station in Mexico City and Naucalpan de Juarez (Primero de Mayo bus station).[12]

The telephone code is 591+ for Santiago Tequixquiac and Colony Wenceslao Labra and telephone code 599+ for Tlapanaloya township.[13] The municipality has available telephone Internet service.

Politics

| Mayor | Time |

|---|---|

| Adrían Rojas Hernández | 1995–1997 |

| Emiliano Cruz Rodríguez | 1997–2000 |

| José Rafael Pérez Martínez | 2000–2003 |

| Gustavo Alonso Donís García | 2003–2006 |

| Enrique Martínez Astorga | 2006–2009 |

| Xóchitl Ramírez Ramírez | 2009–2012 |

| Juan Carlos González García | 2012–2015 |

| Salvador Raúl Vásquez Valencia | 2016–2018 |

Tequixquiac municipality has a town hall. The administration is headed by a municipal president or mayo and includes a treasurer, a municipal secretary and councilors. The municipal seat is Santiago Tequixquiac town. This municipality has a municipal public announcement of police side and good governance (Bando municipal de policía y buen gobierno), are local laws, this is issued each year and published every February 5, the national Constitution Day.

Tequixquiac is divided politically in two towns (Santiago Tequixquiac and Tlapanaloya), neighborhoods, agricola colonies, and rancherías.[14]

Economy

Tequixquiac has produced calcium oxide since the time of the Aztec Empire when Otomi people paid tribute in Hueypoxtla province. The calcium oxide was used by construction and nixtamal, and Spaniards continued with production of calcium oxide in this region as a tribute by construction.[15] During the 19th century Tequixquiac was also recognized for corn agriculture and pulque production inside their haciendas; this beverage was transported to Mexico City on donkeys or mules.

The municipality's economy has traditionally been based in agriculture, especially in the growing of corn, alfalfa, tomato, wheat, chili and bean, mostly used for auto-consumption. However, climatic change has diminished harvests and the growth of commerce in the form of small and medium-sized businesses has grown. Industry here is minimal, consisting of agro-industry in milk and forage; Tequixquiac produces cheese, cream, butter, tostadas and handcraft beer.[1]

Unemployment and lack of economic opportunity within the municipality has led to the departure of Tequixquiac workers to other cities and countries. The tradition of masonry was developed as a source of employment in this region, applies to many different industries.[16]

Demographics

| Town | Population |

| Total | 31,080 |

| Santiago Tequixquiac | 19,772 |

| Tlapanaloya | 6,294 |

| Wenceslao Labra | 1,248 |

| El Crucero | 134 |

| La Heredad | 74 |

At the census of 2010, there were 33,907 people, The population density was 155.4 people per square mile (60.0 people/km2), The median age was twenty-four years. There were 17,113 females and 16,794 males.[17]

Languages

| 2000 language groups[18] | |

|---|---|

| Languages | Population |

| Total | 398 |

| Otomi language | 106 |

| Mazahua language | 55 |

| Other languages | 237 |

Spanish is the mother language for the majority of the people, and in 2005 only 189 persons spoke another language.[19] The next-most-spoken language is Otomi; in Santiago Tequixquiac there are otomi toponyms as Taxdho, Vije and Bomitza (Gumisha). Before Spanish colonization, the land was inhabited by Otomis and Aztecs, also named Chichimeca people. Other languages spoken in Tequixquiac are Mazahua, Nahuatl, Mixtec, Zapotec, Purepecha and Huastec, these languages are spoken by indigenous immigrants to this municipality. The migration to United States of America and elementary education has introduced English language, but it is uncertain how many people speak this language.

Religion

The predominant religion is Catholic Christianity representing 90% of the total population of the municipality. There is a parish belonging to the Diocese of Cuautitlan and a chapel in each neighborhood, district or ranch. The second-largest religious community is that of Jehovah's Witnesses who have a Kingdom Hall located in the suburb of San Mateo and acceptance this denomination has spread rapidly throughout the town. There are also Protestant communities of various denominations as evangelicals, Pentecostals, Methodists, Mormons, Only Christians, and Adventists cornerstone.[20]

In Tequixquiac there has been a presence of Judaism since the Spanish colonial period, descendants of Spanish and Portuguese Sephardic people. The majority of these Crypto-Jews or marranos were absorbed by Roman Catholicism.[1] Another group of people claim not to believe in God and consider themselves atheists, mostly they are young; atheists are on the rise in recent years. Other practicing religions include indigenous cosmogonic philosophy, Santa Muerte cult and Jesús Malverde cult.

| Religion | Population (1970) | Population (1990) |

| Total | 10,276 | 17,995 |

| Roman Catholic | 9,872 | 16,796 |

| Protestantism | 314 | 662 |

| Atheism | 71 | 275 |

| Judaism | 7 | 11 |

| Others | 12 | 202 |

| No specific | n/a | 49 |

Health

Tequixquiac municipality has 4 public ISEM (English: Health Institute of the State of Mexico) clinics in San Mateo, San José, Colonia Adolfo López Mateos and Tlapanaloya town. The principal cases of death are diabetes mellitus, hypertension, cancer and crib death. Other diseases include kidney infections and respiratory problems.[21] The service in public hospitals is attendant in Apaxco, Zumpango and Tecamac municipalities; in Santiago Tequixquiac there are two private hospitals serving mainly births and chronic diseases.

Culture

Architecture

.jpg.webp)

Tequixquiac is a municipality with an architectural heritage built in the viceroy of New Spain. The most-prominent building is the Santiago Apóstol Parish, a temple constructed in 1590 by an indigenous workforce; the architectural style is called tlaquitqui because it incorporates indigenous symbols and concepts. Other Spanish colonial buildings are El Calvario Chapel, San Sebastian hacienda, El Cenicero hacienda, Montero hacienda, Acatlán hacienda and the Mesón de Taxdho; in Tlapanaloya are The Assumption parish of Tlapanaloya, Casa Grande, La Esperanza hacienda, La Heredad Ranch, Stone bridge and many old houses.

In the 19th and 20th centuries important engineering works include the El Tajo channel, Calcium Horns and Chimney, Vicente Guerrero school, Methodist church, Municipal Hall, Cuatro Caminos bridge, old cemetery, Casa de los Párrocos, La Cinco channel, and the Portales and Main Plaza.

Folklore

.JPG.webp)

The Contradanza de las Varas is a traditional creole dance that is performed in the town celebrations of Santiago Tequixquiac and Tlapanaloya, and is not based on indigenous dances.[22][23]

Holy Week is a cultural celebration of Tequixquiac and Tlapanaloya towns. Starting on Palm Sunday, there are processions with colonial sculptures, chants and prayers or recitations at the streets. Holy Friday is a day for folkloric manifestations; on that night, a silent procession is held with great regard.[24]

The concheros is an indigenous dance of Chichimeca people (Otomi and Aztec cultures) danced inside the atrium of church, believed to be from the 20th century by a group formed in Tlapanaloya. They also dance in other towns, at archeological sites, Christian shrines, and at El Arenal, Hidalgo and Chalma.

Music

The wind band Longinos Franco, a native of the Barrio El Refugio, is a guardian and interpreter of the contradanza de Las Varas, and dissemination of music under the guidance note wind symphony, paso doble, marches, a large repertoire of Mexican folk music and modern popular music.[23]

Other musical manifestations are the corridos, songs or popular chants about historical events during the Mexican Revolution. The corrido was later dedicated to the villages, to the people and their customs as the Corrido de Tequixquiac or Corrido de Tlapanaloya.

A musical group Los Bybys, which originated in Tequixquiac in 1991, has appeared in many cities and toured the United States, Argentina, Paraguay, Peru and Bolivia.[25]

Education

.JPG.webp)

Tequixquiac municipality has many elementary schools and kindergartens, covering educational demand. It has among the lowest illiteracy levels in the state at 8%.[26] Tequixquiac has no ingenious bilingual schools, but 298 persons speak an indigenous language.[18]

This municipality has 13 kindergartens, 14 elementary schools, 9 secondary schools and 4 high schools.[27] Tequixquiac has no universities or professional education; young people study at public and private universities in Zumpango, Pachuca, Tizayuca, Mexico City and Metropolitan Area (Ecatepec de Morelos, Cuautitlán Izcalli, Atizapan de Zaragoza, Tlalnepantla de Baz and Naucalpan de Juarez).

Sports and entertainment

.JPG.webp)

.JPG.webp)

.jpg.webp)

The first sport practiced in Tequixquiac was the charrería. When the Spanish first settled in this town, they were under orders to raise horses, but not to allow indigenous to ride. The hills of Tequixquiac had been used to pasture cows and rams, and the Spanish had very large haciendas and found it necessary to employ indigenous people as vaqueros or herdsman, who soon became excellent horsemen.

When the building workers for the Channel of Tequixquiac (second channel) arrived in 1938, they brought with them the practice of racquetball. In Barrio de San Mateo, there is evidence that previously played in front wall of the engineers who built Tequixquiac Tunnel and ports, this area is called the pediment precisely. Today racquetball is played at Deportivo 11 Brothers of Necaxa, a sports complex which also has baseball and basketball.

Another legacy of the engineers is the practice of baseball by elderly adults as Arnaldo Paez Navarro and 74-year-old Don Felix Vasquez Flores. Today baseball is played at Deportivo El Salado, site near to La Cinco and other sports such as association football and basketball.

At Campo Zaragoza there is a sporting area in Santiago Tequixquiac where basketball and association football are practiced. There is also a Cultural Center in Campo Zaragoza where they practice tae kwon do. The municipality has welcomed outside sports, horsemanship, mountain biking, and also has private gyms and a swimming school (Pixan kay).

Camaleones was the first mountain-biking club in Tequixquiac. There are international competitors on mountain bike, and athletes from Tequixquiac participated in the Panamerican games of Guadalajara 2011 and Toronto 2015.[28]

Notable people

- Fortino Hipólito Vera y Talonia, philosopher and writer, bishop of Cuernavaca.

Notable residents

- Gustavo Donis García; Mexican politician, federal deputy and ex-mayor from Tequixquiac.

- Jorge Sánchez García; Mexican politician and worker activist, Luz y Fuerza syndicate clerk and Latinoamerican working syndicate council secretary.

- Manuel Rodríguez Villegas; Mexican writer, architect and activist.

- Polo Vasquez; Poet, songwriter and singer.

Notable visitors

- Alexander von Humboldt, explorer, writer and German naturalist, who visited Tequixquiac in 1804.

- Porfirio Díaz, ex-President of Mexico, who visited Tequixquiac in 1886 and 1900.

- Otilio Montaño, Zapatista soldier, who visited Tequixquiac in 1913.

- Venustiano Carranza, ex-President of Mexico, who visited Tequixquiac in 1917.

- Paul Walker, American actor, who visited Tequixquiac in 2009, sportman in Cerro Mesa Ahuamada trip.

References

- "Enciclopedia de los Municipios de Mexico Estado de Mexico Tequixquiac" (in Spanish). Archived from the original on May 27, 2007. Retrieved 2008-11-27.

- "Invadirá danza folclórica escenarios del Centro Cultural Mexiquense" (in Spanish). México D.F.: Secretaría de Cultura. 2012-06-06. Archived from the original on 2016-04-18.

- Valdés, Gloria Valek (29 June 2018). Agua: reflejo de un valle en el tiempo. UNAM. ISBN 9789683679376. Retrieved 29 June 2018 – via Google Books.

- "Inicio - EL MUNDO". EL MUNDO. Retrieved 29 June 2018.

- INEGI (2009). "Tequixquiac municipality" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-08-08. Retrieved 2018-02-03.

- INEGI. "Link to tables of population data from Census of 2005 INEGI: Instituto Nacional de Estadística, Geografía e Informática". Archived from the original on 2013-04-06. Retrieved 2008-10-25.

- "Medio Físico – Ayuntamiento de Tequixquiac". Tequixquiac.gob.mx. Archived from the original on 29 November 2016. Retrieved 29 June 2018.

- Rodríguez Peláez, Maria Elena, Monografía municipal de Tequixquiac, Denominación y toponinimia, Instituto Mexiquense de Cultura, Toluca de Lerdo, 1999. p.p. 44.

- "Hallan restos fósiles en Tequixquiac". Vanguardia (in Spanish). 2010-02-20.

- "Noticias del día". Pa.gob.mx. Retrieved 29 June 2018.

- "Enciclopedia de los Municipios de México Estado de Sonora Hermosillo" (in Spanish). Mexico: Instituto Nacional para el Federalismo y el Desarrollo Municipal. Archived from the original on June 16, 2011. Retrieved January 13, 2010.

- "LADA de Tlapanaloya, Tequixquiac, Mexico". Portaltelefonico.mx. Retrieved 29 June 2018.

- "Bando Municipal 2016" (PDF). Legislacion.edomewx.gob.mx. Retrieved 29 June 2018.

- "Historia de la producción de cal en el norte de la Cuenca de México" (PDF) (in Spanish). Mexico: Universidad Autónmia del Estado de México. Retrieved May 27, 2016.

- "Plan de desarrollo municipal de Tequixquiac, 2013. page.8" (PDF) (in Spanish). Mexico: Ayuntamiento municipal. Archived from the original (PDF) on April 30, 2014. Retrieved May 27, 2016.

- Municipality of Tequixquiac Archived 2016-03-04 at the Wayback Machine SEDESOL, catálogo de localidades. Archived from the original on May 8, 2016. (in Spanish)

- "Indicadores sociodemográficos de la población total y la población indígena por municipio, 2000" (PDF). Cdi.gob.mx. Retrieved 29 June 2018.

- "Indicadores sociodemográficos de la población total y la población indígena por municipio, 2005" (PDF). Cdi.gob.mx. Retrieved 29 June 2018.

- Rodríguez Peláez, Maria Elena, Monografía municipal de Tequixquiac, Denominación y toponimia, Instituto Mexiquense de Cultura, Toluca de Lerdo, 1999. p.p. 24.

- Rodríguez Peláez, Maria Elena, Monografía municipal de Tequixquiac, Denominación y toponinimia, Instituto Mexiquense de Cultura, Toluca de Lerdo, 1999. p.p. 36-37.

- INAFED. "Link about the municipalities of Mexico (Monografía del municipio de Tequixquiac- Antecedentes Coloniales)". Archived from the original on 2015-09-24. Retrieved 2016-04-16.

- Rodríguez Peláez, Maria Elena, Monografía municipal de Tequixquiac, Denominación y toponinimia, Instituto Mexiquense de Cultura, Toluca de Lerdo, 1999. p.p. 47.

- Tequixquiac: monografía municipal. Gobierno del Estado de México. 29 June 1999. ISBN 9789688414828. Retrieved 29 June 2018 – via Google Books.

- Portal Grupero. "Link about Los Bybys". Retrieved 2016-04-16.

- "ATLAS DE RIEGOS : TEQUIXQUIAC" (PDF). Tequixquiac.gob.mx. Retrieved 29 June 2018.

- "Informe Anual Sobre La Situación de Pobreza y Rezago Social" (PDF). Dof.gob.mx. Retrieved 29 June 2018.

- Alva, Daniel. "JOSÉ JUAN ESCÁRCEGA RUMBO A RIO 2016 - MTB Mexico". Mountainbike.org.mx. Retrieved 29 June 2018.

.JPG.webp)

.jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp)