Tethydraco

Tethydraco is a genus of pterodactyloid pterosaur that lived during the Late Cretaceous period (Maastrichtian stage) of what is now the area of present Morocco, about 66 million years ago. Tethydraco was originally assigned to the family Pteranodontidae. Some researchers argued that subsequently described material suggests that it may have been an azhdarchid, and possibly synonymous with Phosphatodraco, though this has been disputed. The type and only species is T. regalis.[1]

| Tethydraco Temporal range: Late Cretaceous, | |

|---|---|

| |

| Holotype humerus | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Order: | †Pterosauria |

| Suborder: | †Pterodactyloidea |

| Clade: | †Ornithocheiroidea |

| Genus: | †Tethydraco Longrich et al., 2018 |

| Type species | |

| †Tethydraco regalis Longrich et al., 2018 | |

Discovery and naming

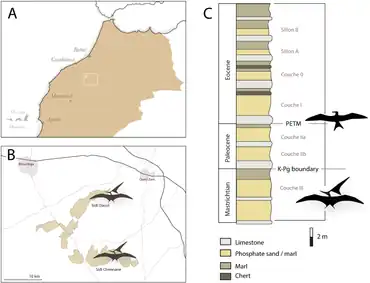

Since 2015, a group of paleontologists has been acquiring pterosaur fossils from commercial Moroccan fossil traders, who obtain these from workers in the phosphate mines on the Khouribga plateau, which is located within the Ouled Abdoun Basin. The purpose of this project is to determine pterosaur diversity in the latest Cretaceous. From this stage, no Konservat-Lagerstätten are known, sites combining a large variety of species with exceptional preservation. It is in such sites that the vast majority of pterosaur fossils and taxa have been discovered. The latest Cretaceous had only produced some partial skeletons of Azhdarchidae. Researchers usually have concluded from this fact that other pterosaur groups had already gone extinct. However, an alternative explanation could be that the poor fossil record caused a distorted image of the true situation through undersampling. To test this hypothesis, an effort was made to collect all pterosaurs bones brought to light by the massive and systematic commercial exploitation of the Khourigba phosphate layers. It transpired that indeed some finds could not be determined as azhdarchids and likely represented other groups. Four of the findings were described as new species in 2018, including Tethydraco.[1]

In 2018, Nicholas R. Longrich, David M. Martill and Brian Andres described and named the type species Tethydraco regalis. The generic name combines a reference to the Tethys, the ocean in the Late Cretaceous separating Africa from Europe and Asia, with a Latin draco, "dragon". The specific name means "royal" in Latin.[1]

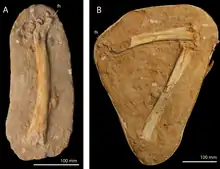

The holotype, FSAC-OB 1, was found in the middle Couche III, itself the lowest phosphate layer complex at Sidi Daoui, dating from the late Maastrichtian. It consists of a left humerus. The bone is relatively crushed. Other specimens have been referred to the species. FSAC-OB 199 is an ulna. FSAC-OB 200 is another ulna. FSAC-OB 201 is a thighbone. FSAC-OB 202 consists of a thighbone with shinbone. The describing authors admitted that a connection between the holotype and the referred specimens is hard to prove, in view of the lack of overlapping material. However, the wide ulnae fit the exceptional distal width of the humerus. The thighbones were, more tentatively, referred because they seemed to be pteranodontid.[1]

Description

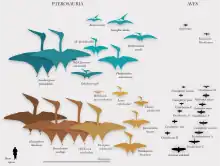

Tethydraco had a wingspan of 5 meters (16 ft) and a body mass of 15 kg (33 lb).[1][2]

The describing authors indicated some traits in which Tethydraco could be distinguished from known pteranodontids. In the humerus, the deltopectoral crest is placed rather proximally, closer to the torso of the animal, its closest border being positioned just proximal to the beginning of the opposite crest, the crista ulnaris. Distally, away from the torso, the humerus has a broad triangular expansion. The bone ridge running to the outer joint condyle has a distinct process pointing to above, when the wing is in a stretched position. The ridge leading to the inner condyle is enlarged and extends towards the torso over a long distance. The ulna is relatively short and wide while its proximal end, towards the humerus, is massively expanded.[1]

Phylogeny

Tethydraco was placed in the family Pteranodontidae; it would have been the youngest known member of that family, since its fossil remains dated back 66 million years ago. Its existence was seen as proof that pterosaur diversity in the Maastrichtian was higher than previously assumed. Apparent pterosaur decline would have been an illusion caused by the Signor–Lipps effect, groups seeming to disappear earlier than a mass extinction because their youngest fossils by chance have been found at somewhat older layers than the extinction event.[1]

Below is a cladogram showing the results of a phylogenetic analysis first presented by Andres and colleagues in 2014, and updated with additional data by Longrich and colleagues in 2018. In this analysis, they found Tethydraco to be the sister taxon of the two species of Pteranodon (P. longiceps and P. sternbergi); all three of them forming the family Pteranodontidae, which is found as the sister taxon of the family Nyctosauridae.[3][1]

| Ornithocheiroidea |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

In 2020, a wing from the same deposit was assigned to the genus; however, the morphology suggested that Tethydraco was an azhdarchid, rather than a pteranodontid as originally proposed, and possibly represented the wing-elements of Phosphatodraco.[4] In 2022, researchers who described Epapatelo noted that the humerus of Epapatelo shares similarity with that of Tethydraco and other non-Nyctosaurus pteranodontoids, and recovered Tethydraco as a pteranodontian closely related to Pteranodon.[5]

Paleoecology

Tethydraco was discovered in the Ouled Abdoun Basin in Morocco. This basin is divided into layers called "Couches", and Tethydraco was discovered in Couche III. It coexisted with the pterosaurs Alcione, Barbaridactylus, Simurghia and Phosphatodraco and the abelisaurid dinosaur Chenanisaurus.[1][6]

References

- Longrich, Nicholas R.; Martill, David M.; Andres, Brian; Penny, David (2018). "Late Maastrichtian pterosaurs from North Africa and mass extinction of Pterosauria at the Cretaceous-Paleogene boundary". PLOS Biology. 16 (3): e2001663. doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.2001663. PMC 5849296. PMID 29534059.

- Paul, Gregory S. (2022). The Princeton Field Guide to Pterosaurs. Princeton University Press. p. 172. doi:10.1515/9780691232218. ISBN 9780691232218. S2CID 249332375.

- Andres, B.; Clark, J.; Xu, X. (2014). "The Earliest Pterodactyloid and the Origin of the Group". Current Biology. 24 (9): 1011–6. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2014.03.030. PMID 24768054.

- Labita, Claudio; Martill, David M. (October 2020). "An articulated pterosaur wing from the Upper Cretaceous (Maastrichtian) phosphates of Morocco". Cretaceous Research. 119: 104679. doi:10.1016/j.cretres.2020.104679. S2CID 226328607.

- Fernandes, Alexandra E.; Mateus, Octávio; Andres, Brian; Polcyn, Michael J.; Schulp, Anne S.; Gonçalves, António Olímpio; Jacobs, Louis L. (2022). "Pterosaurs from the Late Cretaceous of Angola". Diversity. 14 (9). 741. doi:10.3390/d14090741.

- Longrich, N.R.; Pereda-Suberbiola, X.; Jalil, N.-E.; Khaldoune, F.; Jourani, E. (2017). "An abelisaurid from the latest Cretaceous (late Maastrichtian) of Morocco, North Africa". Cretaceous Research. 76: 40–52. doi:10.1016/j.cretres.2017.03.021.