Thai royal funeral

Thai royal funerals are elaborate events, organised as royal ceremonies akin to state funerals. They are held for deceased members of the royal family, and consist of numerous rituals which typically span several months to over a year. Featuring a mixture of Buddhist and animist beliefs, as well as Hindu symbolism, these rituals include the initial rites that take place after death, a lengthy period of lying-in-state, during which Buddhist ceremonies take place, and a final cremation ceremony. For the highest-ranking royalty, the cremation ceremonies are grand public spectacles, featuring the pageantry of large funeral processions and ornate purpose-built funeral pyres or temporary crematoria known as merumat or men. The practices date to at least the 17th century, during the time of the Ayutthaya Kingdom. Today, the cremation ceremonies are held in the royal field of Sanam Luang in the historic centre of Bangkok.

Overview

.jpg.webp)

The main components of a royal funeral do not differ much from regular Thai funerals, which are based on Buddhist beliefs mixed with local animist traditions. Hindu symbolism, a long-standing feature of the monarchy, is also featured prominently. A bathing ceremony is held shortly after death, followed by the rituals of dressing the body and placing it within the kot, a funerary urn used in place of a coffin. The kot is then placed on display and daily Buddhist rites—which include chants by Buddhist monks and the playing of ceremonial music every three hours—are held for an extended period, which today has come to signify lying-in-state in the Western sense. While these rituals were traditionally private affairs, the royal cremation ceremony has long been a public spectacle; those held for the highest-ranking royalty feature temporary crematoria known as merumat, which are purpose-built in the royal field next to the palace. The body is brought to the cremation field in an elaborate procession featuring great funeral carriages, and days of theatrical performances are held.[1][2]

There are many levels of royal funerals, depending on the rank and status of the deceased royal family member. Such distinctions are reflected in details such as the type of kot used, and the type and location of the crematorium—merumat are only built for the monarch and highest-ranking royals; the cremation of lower-ranking royals employ simpler structures known as men, the simpler variants of which were tents of white cloth, or may be held in the permanent crematoria of temples (similarly to most commoners today) instead of purpose-built ones in the royal field. The supreme patriarch and high-ranking Buddhist monks may also receive royal cremations similar to those of lesser royals.[3]

While documentation of historic private rites are scarce, as they were passed on by oral tradition, royal cremation ceremonies have been documented since the Ayutthaya period, and have continued into the current Rattanakosin Kingdom. They were previously very elaborate and grand, but have been much simplified since the funeral of King Chulalongkorn (Rama V) in 1911.[4]

Following the abolishment of absolute monarchy in 1932, King Prajadhipok (Rama VII) abdicated and died in England, and royal funerals became a rare occurrence, apart from that of King Ananda Mahidol (Rama VIII) in 1950 and Queen Sri Savarindira in 1956. The ceremony received somewhat of a revival in the funeral of Queen Rambai Barni (Prajadhipok's widow) in 1985. Royal cremations held since include those of Princess Mother Srinagarindra in 1996, Princess Galyani Vadhana in 2008, Princess Bejaratana in 2012, and King Bhumibol Adulyadej (Rama IX) in 2017.[5][6]

Initial rituals and lying-in-state

Bathing ceremony and sukam sop

The bathing ceremony takes place shortly after death. Today, it is held in the Phiman Rattaya Throne Hall in the Grand Palace, and is attended by members of the royal family and senior government officials. As with common funerals today, this takes place as a ceremonial pouring of water by the attendees, but the water is usually poured over the deceased's feet instead of the hand, as is done for commoners.[lower-alpha 1] After the bathing ceremony, the hair is ritually combed, once upwards and once downwards, and the comb is broken. For high-ranking royals, a gold death mask is placed on the body (after sealing the orifices with wax, in times before embalming).[7]

Next is the sukam sop ritual, i.e. the tying, wrapping and placing of the body in the kot. This is performed by officials of the phusa mala, an ancient court office responsible for, among other things, maintaining the king's wardrobe and attending to the bodies of royals after death.[8] The body is first dressed in white, with the appropriate accessories. It is then ritually tied with undyed string, and wrapped in a white shroud. The body is finally placed in a foetal position in the kot. A chada (pointed crown) is ritually placed on the head of the body, before the lid of the kot is finally closed.[lower-alpha 2][9]

Kot

The kot (from Sanskrit kośa, meaning "container") is a large funerary urn, used to contain the body of the deceased in place of a coffin. It is used for royalty, as well as high-ranking members of the nobility. Today it may also be granted to high-ranking government officials. It consists of two layers: an outer shell, usually ornately decorated, with two opening halves and a pointed lid; and an inner cylindrical container known as long.[lower-alpha 3] There are fourteen types of kot, which are granted to the deceased according to their rank and status. The highest-ranking kot, Phra Kot Thong Yai, is reserved for the king and the highest-ranking royal family members.[10]

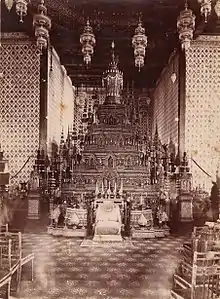

For high-ranking royalty today, the kot is enshrined on a decorated pedestal known as bencha in the Dusit Maha Prasat Throne Hall of the Grand Palace. A long strip of cloth known as phusa yong, tied to the shroud within the kot and passing under the lid, is laid down to symbolically connect to the deceased during the sadappakon ritual. A tube runs down from an opening at the base of the kot, connecting it to a jar (tham phra buppho) hidden beneath the pedestal which serves to collect fluids, as the body was mostly allowed to decompose within the kot in the days before embalming. This often led to undesirable odours, which had to be masked by burning fragrant incenses.[3]

The kot probably derived from the use of burial urns in ancient Southeast Asian traditions, which also featured secondary burials, comparable to the custom of waiting a certain period before cremation. Despite the Sanskrit origin of the term, such urns were not used by Medieval cultures of the Indian Subcontinent, from which the practice of cremation spread to Thailand, along with Buddhism.[11]

During the funeral of Princess Mother Srinagarindra in 1995, the royal body was not physically placed in the kot, in accordance with her wishes. Instead, a coffin was used, placed behind the pedestal which still customarily bore the empty kot. The same was done for the funerals of Princess Galyani Vadhana and King Bhumibol, although Princess Bejaratana opted for her body to be placed in the kot according to tradition.[12]

Daily rites

.jpg.webp)

The kot, containing the body, is enshrined in the throne hall for a period of time (usually at least 100 days). In modern times, this has become analogous to lying-in-state, although the practice predates Western contact and did not originally serve to allow the public to pay their respects. During this time, daily Buddhist rites are held, with chanting by monks around-the-clock, and ceremonial music known as prakhom yam yam is played by the prakhom band every three hours, alongside a piphat nang hong group.[13] Further Buddhist ceremonies are held to mark the 7th, 15th, 50th and 100th days since the death.[14]

During these Buddhist rites, meal offerings (for morning and midday ceremonies) and offerings of cloth on behalf of the dead, known as sadappakon, are made to the monks.[15]

While these rites were also historically private affairs, members of the public have been allowed to pay their respects in the Dusit Maha Prasat Throne Hall since the funeral of King Chulalongkorn, in recent funerals the main public vigils are also livestreamed.[16]

Mourning

Historically, the kingdom's subjects had to shave their heads and dress in white to mourn the death of the king. This practice has also been abandoned since the funeral of King Chulalongkorn. The practice of wearing black for mourning was also a Western import introduced around the King's time.[1][17]

Today, mourning mostly follows Western protocols. The government announces a mourning period to be observed by government officials, and national flags are flown at half-mast.[lower-alpha 4] Public entertainment activities is requested to be withheld for a certain period, and broadcast media also typically suspends entertainment programming as well. Mourning is again observed during the cremation period.[18]

Preparation for cremation

Merumat and men

_Wellcome_L0020122.jpg.webp)

As the royal funerary services take place, preparations are made and a temporary royal crematorium—a merumat or men (rendered as phra merumat and phra men in the royal register—see explanation under § Glossary below), depending on the rank of the deceased—is erected in the royal field next to the palace. This is Sanam Luang in today's Rattanakosin period; its role as the site of royal cremations explains its former name, Thung Phra Men, which means "royal cremation field".[19]

The construction of merumat for royal cremations date to the Ayutthaya period, as Hindu beliefs were absorbed from the Khmer Empire. Following the Hindu-Buddhist ideology of divine kingship, the king was believed to be semi-divine, and the merumat symbolizes Mount Meru, the centre of the universe atop which lies the home of the gods, to which the king would return after death.[20][21]

The earliest merumat was probably erected during the reign of King Prasat Thong (1629–1656), and modelled after Angkor Wat. Ayutthaya-period merumat were gigantic structures. The one built for King Narai (died 1688) was recorded as being 3 sen (60 fathoms) tall—120 metres according to modern conversion rates. Despite the usual translation of merumat as "funeral pyre", it was actually a mainly decorative structure, within which the much smaller actual pyre was housed. Merumat were always temporary structures purpose-built for the ceremony, and featured the exquisite craftsmanship of the kingdom's best artisans.[20]

The construction of the merumat often took months, if not years, to complete. This, along with the fact that the cremation had to take place in the dry season, partly contributed to the practice of waiting lengthy periods before cremation. Often, by the time a merumat or men was completed, it would be used for multiple cremations, as multiple royal deaths had occurred.[14]

The practice of building very large merumat was last seen in the funeral of King Mongkut (Rama IV, died 1868). His successor, King Chulalongkorn, expressed his distaste of the waste of labour and money, and ordered that a simple structure be built for his cremation instead. Since then, royal funerals have employed such simplified designs for the merumat and men, and the terms are now only used to distinguish the rank of the deceased.[20]

Following cremation, the merumat or men is disassembled and the components and materials are usually donated to Buddhist temples or to charity. Materials from the men of Prince Siriraj Kakudhabhand in 1888, for example, were used to build Siriraj Hospital.[22]

Royal funeral chariots

.jpg.webp)

As the merumat is being built, restoration and maintenance work is also done to prepare the royal funeral chariots for the cremation ceremony procession, and practice sessions are held.[23]

Prior to cremation

A few days prior to the cremation ceremony, phusa mala officials will remove the body from the kot in order to remove the materials used during sukam sop, and re-wrap the body in a new shroud. In the past, the partially-decomposed flesh would also be removed and stripped from the bones, in order to be cremated separately, but embalming has rendered this process unnecessary. The sukam sop materials, together with the bodily fluids collected in the tham phra buppho, are cremated in a small ceremony known as thawai phloeng phra buppho. (This was not done for recent royal funerals where the body was placed in a coffin; the last time this ceremony happened was prior to the 2012 royal cremation of Princess Bejaratana.)[3]

The kot will be carried to the merumat or men on the day of the cremation ceremony (see § Funeral processions below). Sometimes, however, the body might actually be moved from its place of enshrinement before the morning of the procession, in an unofficial step that is not part of the ceremonies. It takes place at night, somewhat secretly, leading the practice to be known as lak sop (lit. "stealing of the body"). This is done out of necessity or for convenience, e.g. in cases where the site is far from the procession route, or, in modern times, where body is placed in a coffin rather than the kot. It is an old tradition dating back to the Ayutthaya kings which saves time for the royal funeral procession within hours.[24][25]

Cremation ceremony

The royal cremation ceremonies were historically elaborate and celebratory events. Those for the king usually lasted fourteen days and nights, and included processions of relics of the Buddha, fireworks, and days of festivities. Today, it usually lasts about five days, and mainly consists of funeral processions bringing the royal body to the merumat or men, the cremation, and processions returning the cremated remains and ashes to the palace.[1] This section will describe the current rituals for the highest-ranking royals (those held in Sanam Luang), and use merumat to refer to both merumat or men, for simplicity.

Funeral processions

Final Buddhist rites are held in the evening before the cremation ceremony. The following morning, the kot carrying the royal remains is carried to the merumat via a series of funeral processions.[1][26]

In the first procession, the kot is brought onto the royal palanquin known as Phra Yannamat Sam Lam Khan. It is then carried from Dusit Maha Prasat Throne Hall, out of the Grand Palace, and to the front of Wat Pho, where it is transferred to the royal funeral chariot (either the Maha Phichai Ratcharot or Vejayanta Ratcharot). The second procession—the most elaborate—then proceeds towards and enters Sanam Luang, where the kot is transferred either again to Phra Yannamat Sam Lam Khan, or to a royal gun carriage (for kings who held the title of Head of the Armed Forces or royal family members holding high military ranks in the Royal Thai Armed Forces, a tradition initiated on the wishes of King Vajiravudh in 1926). The third procession then circumambulates the merumat three times in a counter-clockwise fashion, before the kot is brought into the merumat.[1][26] During the processions, ceremonial music is played, and gun salutes are fired.[26]

Cremation

As the kot is brought onto the pyre (known as chittakathan) within the merumat, the outer shell is removed and replaced with a shell of carved sandalwood known as phra kot chan (and/or phra hip chan if the deceased was placed in a coffin). Further Buddhist rites are held, until the cremation takes place in the evening.[26]

During the first cremation, which is a mock ceremonial burning, the king lights the cremation fire and lays the first dok mai chan—artificial flowers made of sandalwood and used ceremonially in cremations. The other guests then follow suit, laying flowers one by one. The ritual is repeated later in the night, with a smaller group of guests, when the actual cremation takes place. On the first lighting a 21-gun salute and a three-volley salute are both fired in the Sanam Luang field.[26]

Interment of remains and ashes

The day after the cremation, a ceremony takes place where the cremated remains and ashes are viewed and placed in smaller urns. The remains (atthi) are placed in a small kot known as phra kot phra atthi, while the ashes (sarirangkhan) are placed in a rounder-shaped urn called pha-op. They are then transported back to the Grand Palace in a fourth procession after a morning service and breakfast by the monks. The remains are brought into the Dusit Maha Prasat Throne Hall, while the ashes are temporarily placed in the Phra Si Rattana Chedi stupa in Wat Phra Kaew.[26]

The next day, final Buddhist rites are held for the cremated remains in the morning, before the kot is transported the short distance to Chakri Maha Prasat Throne Hall, where the remains will be interred, in the fifth procession. The sixth procession carries the royal ashes to the temple where they will be interred, usually at Wat Ratchabophit, where the Royal Cemetery is located, unlike the five past processions in current royal funerals the ashes are transported to the interment site in a royal automobile with escorts provided by the 29th Cavalry Squadron, Royal Horse Guards.[26]

Entertainment

Entertainments and theatrical performances used to feature largely during royal cremation ceremonies, but were discontinued during the funeral of King Chulalongkorn. The practice was revived, at the suggestion of Princess Sirindhorn, during the funeral of Princess Mother Srinagarindra in 1996.[12]

Modern developments

.jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp)

As an ongoing tradition, royal funerals have undergone changes and adaptations throughout the years. Much of the ceremony has been simplified since the funeral of King Chulalongkorn, and the development of embalming has changed the body-handling process. Recent developments introduced in the late twentieth century include live television broadcasts of the ceremony, as well as increased public participation. The public was first allowed to symbolically participate in the royal bathing ceremony in front of royal portraits during the funeral of Princess Mother Srinagarindra, and was allowed to co-host the funeral rites in the funeral of Princess Galyani Vadhana in 2008.[27][28] The phra kot chan of Queen Rambai Barni and Princess Bejaratana have also been preserved, along with the phra kot chan and phra hip chan of Princess Mother Srinagarindra, Princess Galyani Vadhana and King Bhumibol Adulyadej, instead of being burnt in the pyre.[29] Electric furnaces were introduced in the cremation ceremonies of Princess Galyani Vadhana.[10]

Related traditions

Similar royal funerary traditions are observed in Cambodia and, historically, in Laos, as the countries historically shared the same cultural sphere as Thailand. In Cambodia, the late King Norodom Sihanouk received a royal cremation in 2013, more than 50 years after the ceremony was last held.[30] The last royal cremation to take place in Laos was that of King Sisavang Vong in 1961; the country was later taken over by the Communists, and its last king, Sisavang Vatthana, died in captivity.[31]

Galleries

Royal crematoria

Queen Debsirindra (1862)

Queen Debsirindra (1862) Vice-King Pinklao (1867)

Vice-King Pinklao (1867) Queen Saovabha Phongsri (1920)

Queen Saovabha Phongsri (1920) Prince Chakrabongse Bhuvanath (1920)

Prince Chakrabongse Bhuvanath (1920) King Vajiravudh (1926)

King Vajiravudh (1926).jpg.webp) Princess Galyani Vadhana (2008)

Princess Galyani Vadhana (2008) Princess Bejaratana (2012)

Princess Bejaratana (2012)

Processions

First procession (King Bhumibol Adulyadej, 2017)

First procession (King Bhumibol Adulyadej, 2017) Second procession (Princess Bejaratana, 2012)

Second procession (Princess Bejaratana, 2012) Third procession (King Vajiravudh, 1926)

Third procession (King Vajiravudh, 1926)_from_the_royal_crematorium_to_the_Grand_Palace.JPG.webp) Fourth procession (Princess Bejaratana, 2012)

Fourth procession (Princess Bejaratana, 2012)

Phra Merumat of King Bhumibol Adulyadej (2017)

Phra Merumat of King Bhumibol Adulyadej

Phra Merumat of King Bhumibol Adulyadej The Principal Pavilion

The Principal Pavilion Dismantling Pavilion

Dismantling Pavilion Monk's Chanting Pavilion

Monk's Chanting Pavilion Lion and Makara

Lion and Makara The lion-like mythical creature

The lion-like mythical creature The Garuda

The Garuda The kneeling deities

The kneeling deities Ganesha at Phra Merumat of King Bhumibol Adulyadej

Ganesha at Phra Merumat of King Bhumibol Adulyadej Fireguard Screen of Phra Merumat of King Bhumibol Adulyadej

Fireguard Screen of Phra Merumat of King Bhumibol Adulyadej Phra Merumat of King Bhumibol Adulyadej during the night

Phra Merumat of King Bhumibol Adulyadej during the night

Glossary

This glossary provides spellings, pronunciations, and definitions of the Thai terms used in this article. Formatting of the glossary is shown in the following example entry:

- root word

- Thai spelling • [pronunciation] • royal term, alternative royal term* (if applicable)

definition and/or further explanation

The Thai language uses a special register, known as rachasap, to address royalty. These are usually indicated by the prefixes phra (พระ, pronounced [pʰráʔ]) and boromma (บรม, [bɔ̄.rōm.maʔ]). For example, a kot (ⓘ) used for royalty is referred to as phra kot (ⓘ), and one used for the king or queen is referred to as phra boromma kot (ⓘ). In the following entries, an asterisk (*) denotes royal terms used for the king or queen.

- atthi

- อัฐิ • [ʔàt.tʰìʔ] ⓘ • phra atthi, phra boromma atthi *

cremated remains (bones) - bencha

- เบญจา • [bēn.tɕāː] ⓘ • phra bencha

five-tiered pedestal used to support the kot - buppho

- บุพโพ • [bùp.pʰōː] ⓘ • phra buppho

lymph and bodily fluids - chittakathan

- จิตกาธาน • [tɕìt.tà.kāː.tʰāːn] ⓘ • phra chittakathan

pyre (located within the men or merumat); referred to as choeng takon (เชิงตะกอน) for commoners - dok mai chan

- ดอกไม้จันทน์ • [dɔ̀ːk.máj.tɕān] ⓘ

sandalwood flower; an artificial flower ritually burned during cremation - kot

- โกศ • [kòːt] ⓘ • phra kot, phra boromma kot *

funerary urn - lak sop

- ลักศพ • [lák.sòp] • lak phra sop, lak phra boromma sop *

"stealing of the body"; the practice of moving the body from its place of enshrinement at night, before the funeral procession - long

- ลอง • [lɔ̄ːŋ] ⓘ • phra long

inner or outer layer of the funerary urn; sometimes considered part of the kot, other times considered distinct from it, as the terms have switched meanings over time - men

- เมรุ • [mēːn] ⓘ • phra men

crematorium - merumat

- เมรุมาศ • [mēːrú.mâːt] ⓘ • phra merumat

crematorium; historically referred to the very large ones built for kings and queens, now mostly resembling men in appearance, though the term is still reserved for kings and queens - pha-op

- ผอบ • [pʰàʔɔ̀p] ⓘ

small jar or urn; in this context, used to contain the royal ashes (sarirangkhan) - phra kot chan

- พระโกศจันทน์ • [pʰrá.kòːt.tɕān] ⓘ

kot with outer shell of carved sandalwood, used for cremation - phra kot phra atthi

- พระโกศพระอัฐิ • [pʰrá.kòːt.pʰráʔàt.tʰìʔ] ⓘ • phra kot phra boromma atthi

small kot for containing the cremated remains (atthi) - Phra Kot Thong Yai

- พระโกศทองใหญ่ • [pʰrá.kòːt.tʰɔ̄ːŋ.jàj] ⓘ

name of the kot of highest rank, lit. "great gold kot" - Phra Yannamat Sam Lam Khan

- พระยานมาศสามลำคาน • [pʰrá.jāːn.na.mâːt.sǎːm.lām.kʰāːn] ⓘ

name of the royal palanquin (yannamat) used to transport the kot during the funeral processions, lit. "three-beamed royal palanquin" - phusa mala

- ภูษามาลา • [pʰūː.sǎː.māː.lāː] ⓘ

ancient court office responsible for maintaining the king's wardrobe, as well as cutting the king's hair, holding the king's umbrella, and attending to bodies of royals (specifically sukam sop) after death; its officials are referred to as chao phanak-ngan phusa mala (เจ้าพนักงานภูษามาลา) - phusa yong

- ภูษาโยง • [pʰūː.sǎː.jōːŋ] ⓘ • phra phusa yong

long strip of cloth leading from the lid of the kot or coffin and laid in front Buddhist monks during sadappakon or bangsukun; referred to as pha yong (ผ้าโยง) for commoners - prakhom yam yam

- ประโคมย่ำยาม • [pra.kʰōːm.jâm.jāːm] ⓘ

to play ceremonial music to mark each three-hour period of the day - sadappakon

- สดับปกรณ์ • [sa.dàp.pa.kɔ̄ːn] ⓘ

offering of cloth to Buddhist monks on behalf of the dead; referred to as bangsukun (บังสุกุล, from Pali paṃsukūla) for commoners; may also refer to the specific chant used for such rituals, i.e. satta pakaraṇa - sarirangkhan

- สรีรางคาร • [sa.rīː.rāːŋ.kʰāːn] ⓘ • phra sarirangkhan, phra boromma sarirangkhan *

cremated ashes - sop

- ศพ • [sòp] ⓘ • phra sop, phra boromma sop *

dead body - sukam sop

- สุกำศพ • [sù.kām.sòp] ⓘ

tying, wrapping and placing of the body in the kot or coffin; referred to as mat tra sang (มัดตราสัง) for commoners - tham phra buppho

- ถ้ำพระบุพโพ • [tʰâm.pʰrá.bùp.pʰōː] ⓘ

jar hidden beneath the bencha to collect bodily fluids (buppho) draining from the kot - thawai phloeng phra buppho

- ถวายเพลิงพระบุพโพ • [tʰa.wǎj.pʰlɤ̄ːŋ.pʰrá.bùp.pʰōː] ⓘ

cremation of the bodily fluids (buppho) collected in the tham phra buppho, along with the materials used for sukam sop - yannamat

- ยานมาศ • [jāːn.na.mâːt] ⓘ • phra yannamat

palanquin, carried by men on their shoulders, used to transport the kot

Notes

- An exception is when the king attends the funeral of a lower-ranking royal, in which he pours water over the deceased's chest.

- Some sources indicate that the chada is actually removed before the lid is closed, though some state that it is removed later when the kot is re-opened before cremation (see § Prior to cremation). In recent funerals where the body is placed in a Western style coffin, the chada is placed beside the body instead.

- The meanings of kot and long have become swapped over time; according to some sources, long refers to the outer shell, while kot actually means the inner container.

- Technically, such government decrees apply only to government agencies and officials, although members of the public usually follow suit.

References

- Jobkolsuek, Saimai. "โบราณราชประเพณีเนื่องในการพระบรมศพและพระศพ" (PDF). Bureau of the Royal Household. Retrieved 1 October 2017.

- "มองประวัติศาสตร์ผ่านงานพระราชพิธีฯ ส่งเสด็จครั้งสุดท้ายก่อนทรงสู่นิรันดร". Manager Daily. 18 November 2008. Retrieved 29 September 2017.

- คำศัพท์ที่เกี่ยวเนื่องกับงานพระราชพิธีพระบรมศพ พระบาทสมเด็จพระปรมินทรมหาภูมิพลอดุลยเดช (PDF). Bangkok: Fine Arts Department. December 2016. ISBN 978-616-283-305-2. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2 October 2017. Retrieved 1 October 2017.

- "ย้อนรอย 'พระราชพิธีพระบรมศพและพระศพ' สมัยสุโขทัยถึงรัตนโกสินทร์". Matichon Online (in Thai). 26 February 2017. Retrieved 1 October 2017.

- "ย้อนวันวาน พระราชพิธีถวายพระเพลิงพระบรมศพ". Post Today (in Thai). 6 December 2016. Archived from the original on 2 October 2017. Retrieved 1 October 2017.

- "Royal Cremation for His Majesty King Bhumibol Adulyadej". Public Relations Department. 27 April 2017. Retrieved 2 October 2017.

- "เปิดข้อมูลโบราณราชประเพณี "สรงน้ำพระบรมศพและพระศพ"". Matichon Online (in Thai). 14 October 2016. Retrieved 29 September 2017.

- Royal Institute (2013). พจนานุกรมฉบับราชบัณฑิตยสถาน พ.ศ. 2554 [Royal Institute Dictionary B.E. 2554] (in Thai). Bangkok: Nanmee Books. ISBN 978-616-7073-56-9.

- ห้องเรียนประวัติศาสตร์ศิลป์ (19 October 2016). "พระชฎาห้ายอด ยังใช้ทรงพระบรมศพพระมหากษัตริย์เมื่อสวรรคต". Silpa Wattanatham (Art & Culture Magazine) (in Thai). Retrieved 4 October 2017.

- "เรื่องพระโกศทรงพระศพ และการพระราชทานเพลิงพระศพ". Sarakadee (in Thai) (286). December 2013. Retrieved 29 September 2017.

- Uitekkeng, Komkrit (28 October 2016). "พิธีเกี่ยวกับความตายในศาสนาพราหมณ์-ฮินดู". Matichon Weekly (in Thai). Retrieved 1 October 2017.

- Bunnag, Rome (23 December 2017). "เป็นครั้งแรกที่พระศพ "สมเด็จย่า" และ "พระพี่นาง" ไม่ได้บรรจุลงพระโกศ แต่บรรจุในพระหีบ (๕)". Manager Online (in Thai). Retrieved 1 October 2017.

- "การประโคมย่ำยาม" (in Thai). Fine Arts Department. 17 October 2016. Retrieved 4 October 2017.

- "เกร็ดประวัติศาสตร์ งานพระราชพิธีพระบรมศพจอมกษัตริย์ไทย". Thai Rath Online (in Thai). 19 January 2017. Retrieved 1 October 2017.

- "ใครคือ 'พระพิธีธรรม' – Manager Online". Manager Online (in Thai). 31 January 2008. Retrieved 1 October 2017.

- Meetam, Thiti (24 November 2016). "ธรรมเนียมพระบรมศพ และพระศพเจ้านายสมัยรัตนโกสินทร์". Khaosod (in Thai). No. 9493. p. 17. Retrieved 1 October 2017.

- "รู้จักวิธีการไว้ทุกข์ "สีเครื่องแต่งกาย" ตามธรรมเนียมพระบรมศพและพระศพเจ้านาย". Prachachat Online (in Thai). 14 October 2016. Archived from the original on 2 October 2017. Retrieved 1 October 2017.

- Jittapong, Khettiya; Temphairojana, Pairat (14 October 2016). "Thailand's mourning for king may soften economy temporarily". Reuters. Retrieved 4 October 2017.

- "ย้อนอดีต "สนามหลวง-ทุ่งพระเมรุ" สถานที่ประกอบพิธีถวายพระเพลิงพระบรมศพ". Manager Online (in Thai). 7 November 2016. Retrieved 1 October 2017.

- Bunnag, Rome (7 December 2016). ""พระเมรุมาศ" สุดยอดของศิลปกรรมแต่ละยุคสมัย! ส่งเสด็จสู่สวรรค์ชั้นดาวดึงส์บนยอดเขาพระสุเมรุ ศูนย์กลางของจักรวาล!!". Manager Online. Retrieved 29 September 2017.

- Mydans, Seth (8 May 2017). "Building a Vision of Heaven for Thailand's 'God'". The New York Times. Retrieved 2 October 2017.

- Jumsai, Sumet (2 April 2012). "The Royal Pyre as Mount Meru – The Nation". The Nation. Retrieved 2 October 2017.

- "Golden chariot restored for Thai king's 'ascent to heaven'". Reuters. 7 February 2017. Retrieved 4 October 2017.

- Youmangmee, Nontaporn (June 2009). "ลักพระศพ-ลักศพ : ธรรมเนียมการพระศพในยามวิกาล" (PDF). Silpa Wattanatham (Art & Culture Magazine) (in Thai). 30 (8): 34–35. Retrieved 22 October 2017.

- "Traditional ceremony of 'stealing the royal body' proceeds – The Nation". Retrieved 25 October 2017.

- ทรงกลด, อัมพร (19 September 2008). "สารคดีบันทึก : พฤศจิกายน ๒๕๕๑ ส่งเสด็จสมเด็จพระเจ้าพี่นางเธอฯ สู่สวรรคาลัย". Sarakadee (in Thai) (286). Retrieved 1 October 2017.

- ""อ.ธงทอง" เผยสมัย ร.9 ประชาชนมีส่วนร่วมในพระราชพิธีมากขึ้น-หลายอย่างที่เห็นไม่เคยมีมาก่อน". Prachachat Online (in Thai). 17 November 2016. Archived from the original on 29 September 2017. Retrieved 29 September 2017.

- Rojanaphruk, Pravit (23 November 2016). "King's Funeral Rites Will Continue Tradition of Accessibility, Expert Says". Khaosod English. Retrieved 4 October 2017.

- Bunnag, Rome (26 December 2017). "พระโกศจันทน์ เริ่มมาแต่สมัยพุทธกาล! จนถึงพระบรมศพสมเด็จพระนางเจ้ารำไพพรรณี... สมเด็จพระเทพฯจึงให้งดเผาศิลปะอันล้ำค่า!!". Manager Online (in Thai). Retrieved 2 October 2017.

- Freeman, Joe; Kunthear, Mom (1 February 2013). "A royal funeral for the ages". Phnom Penh Post. Retrieved 2 October 2017.

- "Laos: Collapse". Time. 5 May 1961. Retrieved 2 October 2017.

Further reading

- "Royal Cremation Ceremony for the late King Bhumibol Adulyadej". Bangkok Post. Bangkok Post Public Company Limited. Retrieved 30 September 2018.

- Inton, Chris; Scarr, Simon; Wu, Jin; Cai, Weiyi; Wang, Jessica (25 October 2017). "Thai Royal Funeral: A Final Farewell to Rama IX". Reuters Graphics. Reuters. Retrieved 27 October 2017.