Ernst Mach

Ernst Waldfried Josef Wenzel Mach (/mɑːx/ MAHKH, German: [ɛʁnst ˈmax]; 18 February 1838 – 19 February 1916) was an Austrian[2] physicist and philosopher, who contributed to the physics of shock waves. The ratio of the speed of a flow or object to that of sound is named the Mach number in his honour. As a philosopher of science, he was a major influence on logical positivism and American pragmatism.[3] Through his criticism of Newton's theories of space and time, he foreshadowed Einstein's theory of relativity.[4]

Ernst Mach | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | Ernst Waldfried Josef Wenzel Mach 18 February 1838 |

| Died | 19 February 1916 (aged 78) |

| Citizenship | Austria |

| Education | University of Vienna (PhD, 1860; Dr. phil. hab, 1861) |

| Known for | Mach band Mach diamonds Mach number Mach reflection Mach wave Mach's principle Criticism of Newton's bucket argument[1] Empirio-criticism Oblique effect Relationalism Shock waves Stereokinetic stimulus |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Physicist |

| Institutions | University of Graz Charles-Ferdinand University (Prague) University of Vienna |

| Thesis | Über elektrische Ladungen und Induktion (1860) |

| Doctoral advisor | Andreas von Ettingshausen |

| Doctoral students | Heinrich Gomperz Ottokar Tumlirz |

| Other notable students | Andrija Mohorovičić |

| Signature | |

| Notes | |

He was the godfather of Wolfgang Pauli. The Mach–Zehnder interferometer is named after his son Ludwig Mach, who was also a physicist. | |

Biography

Mach was born in Chrlice (German: Chirlitz), Moravia, Austrian Empire (part of Brno, in the Czech Republic). His father, who had graduated from Charles-Ferdinand University in Prague, acted as tutor to the noble Brethon family in Zlín in eastern Moravia. His grandfather, Wenzl Lanhaus, an administrator of the Chirlitz estate, was also master builder of the streets there. His activities in that field later influenced Ernst Mach's theoretical work. Some sources give Mach's birthplace as Tuřany (German: Turas, also part of Brno), the site of the Chirlitz registry office. It was there that Mach was baptised by Peregrin Weiss. Mach later became a socialist and an atheist,[5] but his theory and life was sometimes compared to Buddhism. Heinrich Gomperz called Mach the "Buddha of Science" because of his phenomenalist approach to the "Ego" in his Analysis of Sensations.[6][7]

Up to the age of 14, Mach was educated at home by his parents. He then entered a Gymnasium in Kroměříž (German: Kremsier), where he studied for three years. In 1855 he became a student at the University of Vienna, where he studied physics and for one semester medical physiology, receiving his doctorate in physics in 1860 under Andreas von Ettingshausen with the thesis Über elektrische Ladungen und Induktion, and his habilitation the following year. His early work focused on the Doppler effect in optics and acoustics. In 1864, he took a job as professor of mathematics at the University of Graz after he had turned down the position of a chair in surgery at the University of Salzburg to do so, and in 1866 he was appointed professor of physics. During that period, Mach continued his work in psycho-physics and in sensory perception. In 1867, he took the chair of experimental physics at the Charles-Ferdinand University, where he stayed for 28 years before returning to Vienna.[8]

Mach's main contribution to physics involved his description and photographs of spark shock-waves and then ballistic shock-waves. He described how when a bullet or shell moved faster than the speed of sound, it created a compression of air in front of it. Using schlieren photography, he and his son Ludwig photographed the shadows of the invisible shock waves. During the early 1890s Ludwig invented a modification of the Jamin interferometer that allowed for much clearer photographs.[8] But Mach also made many contributions to psychology and physiology, including his anticipation of gestalt phenomena, his discovery of the oblique effect and of Mach bands, an inhibition-influenced type of visual illusion, and especially his discovery of a non-acoustic function of the inner ear that helps control human balance.

One of the best-known of Mach's ideas is the so-called "Mach principle", the physical origin of inertia. This was never written down by Mach, but was given a graphic verbal form, attributed by Philipp Frank to Mach: "When the subway jerks, it's the fixed stars that throw you down."

Mach also became well known for his philosophy, developed in close interplay with his science.[lower-alpha 1] Mach defended a type of phenomenalism recognizing only sensations as real. That position seemed incompatible with the view of atoms and molecules as external mind-independent things. He famously declared, after an 1897 lecture by Ludwig Boltzmann at the Imperial Academy of Science in Vienna, "I don't believe that atoms exist!"[10] From about 1908 to 1911, Max Planck criticised Mach's reluctance to acknowledge the reality of atoms as incompatible with physics. Einstein's 1905 demonstration that the statistical fluctuations of atoms allowed measurement of their existence without direct individuated sensory evidence marked a turning point in the acceptance of atomic theory. Some of Mach's criticisms of Newton's position on space and time influenced Einstein, but later, Einstein realised that Mach was basically opposed to Newton's philosophy and concluded that his physical criticism was not sound.

.jpg.webp)

In 1898, Mach survived a paralytic stroke, and in 1901, he retired from the University of Vienna and was appointed to the upper chamber of the Austrian Parliament. On leaving Vienna in 1913, he moved to his son's home in Vaterstetten, near Munich, where he continued writing and corresponding until his death in 1916, one day after his 78th birthday.[8]

Physics

Most of Mach's initial studies in experimental physics concentrated on the interference, diffraction, polarization and refraction of light in different media under external influences. From there followed explorations in supersonic fluid mechanics. Mach and physicist-photographer Peter Salcher presented their paper on this subject[11] in 1887; it correctly describes the sound effects observed during the supersonic motion of a projectile. They deduced and experimentally confirmed the existence of a shock wave of conical shape, with the projectile at the apex.[12] The ratio of the speed of a fluid to the local speed of sound vp/vs is called the Mach number after him. It is a critical parameter in the description of high-speed fluid movement in aerodynamics and hydrodynamics. Mach also contributed to cosmology the hypothesis known as Mach's principle.[8]

Philosophy of science

Empirio-criticism

From 1895 to 1901, Mach held a newly created chair for "the history and philosophy of the inductive sciences" at the University of Vienna.[lower-alpha 2] In his historico-philosophical studies, Mach developed a phenomenalistic philosophy of science that became influential in the 19th and 20th centuries. He originally saw scientific laws as summaries of experimental events, constructed for the purpose of making complex data comprehensible, but later emphasized mathematical functions as a more useful way to describe sensory appearances. Thus, scientific laws, while somewhat idealized, have more to do with describing sensations than with reality as it exists beyond sensations.[lower-alpha 3]

The goal which it (physical science) has set itself is the simplest and most economical abstract expression of facts.

When the human mind, with its limited powers, attempts to mirror in itself the rich life of the world, of which it itself is only a small part, and which it can never hope to exhaust, it has every reason for proceeding economically.

In reality, the law always contains less than the fact itself, because it does not reproduce the fact as a whole but only in that aspect of it which is important for us, the rest being intentionally or from necessity omitted.

In mentally separating a body from the changeable environment in which it moves, what we really do is to extricate a group of sensations on which our thoughts are fastened and which is of relatively greater stability than the others, from the stream of all our sensations. Suppose we were to attribute to nature the property of producing like effects in like circumstances; just these like circumstances we should not know how to find. Nature exists once only. Our schematic mental imitation alone produces like events.

Mach's positivism influenced many Russian Marxists, such as Alexander Bogdanov.[13] In 1908, Lenin wrote a philosophical work, Materialism and Empirio-criticism,[14] in which he criticized Machism and the views of "Russian Machists". His main criticisms were that Mach's philosophy led to solipsism and to the absurd conclusion that nature did not exist before humans:

If bodies are "complexes of sensations," as Mach says, or "combinations of sensations," as Berkeley said, it inevitably follows that the whole world is but my idea. Starting from such a premise it is impossible to arrive at the existence of other people besides oneself: it is the purest solipsism. ...if [Mach] does not admit that the "sensible content" is an objective reality, existing independently of us, there remains only a "naked abstract" I, an I infallibly written with a capital letter and italicised, equal to "the insane piano, which imagined that it was the sole existing thing in this world." If the "sensible content" of our sensations is not the external world then nothing exists save this naked I engaged in empty "philosophical" acrobatics.

— Chapter 1.1, "Sensations And Complexes Of Sensations"

Empirio-criticism is the term for the rigorously positivist and radically empiricist philosophy established by the German philosopher Richard Avenarius and further developed by Mach, which claims that all we can know is our sensations and that knowledge should be confined to pure experience.[15]

In accordance with empirio-critical philosophy, Mach opposed Ludwig Boltzmann and others who proposed an atomic theory of physics. Since one cannot observe things as small as atoms directly, and since no atomic model at the time was consistent, the atomic hypothesis seemed unwarranted to Mach, and perhaps not sufficiently "economical". Mach had a direct influence on the Vienna Circle philosophers and logical positivism in general.

Several principles are attributed to Mach that distill his ideal of physical theorization, called "Machian physics":

- It should be based entirely on directly observable phenomena (in line with his positivistic leanings)[lower-alpha 4]

- It should completely eschew absolute space and time in favor of relative motion[16]

- Any phenomena that seem attributable to absolute space and time (e.g., inertia and centrifugal force) should instead be seen as emerging from the distribution of matter in the universe.[17]

The last is singled out, particularly by Einstein, as "the" Mach's principle. Einstein cited it as one of the three principles underlying general relativity. In 1930, he wrote, "it is justified to consider Mach as the precursor of the general theory of relativity",[18] though Mach, before his death, apparently rejected Einstein's theory.[lower-alpha 5] Einstein knew that his theories did not fulfill all Mach's principles, and neither has any subsequent theory, despite considerable effort.

Phenomenological constructivism

According to Alexander Riegler, Mach's work was a precursor to the influential perspective known as constructivism.[19] Constructivism holds that all knowledge is constructed rather than received by the learner. He took an exceptionally non-dualist, phenomenological position. The founder of radical constructivism, von Glasersfeld, gave a nod to Mach as an ally.

Physiology

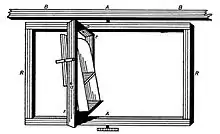

In 1873, independently of each other,[20] Mach and the physiologist and physician Josef Breuer discovered how the sense of balance (i.e., the perception of the head's imbalance) functions, tracing its management by information the brain receives from the movement of a fluid in the semicircular canals of the inner ear. That the sense of balance depends on the three semicircular canals was discovered in 1870 by the physiologist Friedrich Goltz, but Goltz did not discover how the balance-sensing apparatus functions. Mach devised a swivel chair to test his theories, and Floyd Ratliff has suggested that this experiment may have paved the way to Mach's critique of a physical conception of absolute space and motion.[21]

Psychology

In the area of sensory perception, psychologists remember Mach for the optical illusion called Mach bands. The effect exaggerates the contrast between edges of the slightly differing shades of gray as soon as they touch, by triggering edge-detection in the human visual system.[8][22]

More clearly than anyone before or since, Mach made the distinction between what he called physiological (specifically visual) and geometrical spaces.[23]

Mach's views on mediating structures inspired B. F. Skinner's strongly inductive position, which paralleled Mach's in the field of psychology.[24]

Eponyms

In homage his name was given to:

- 3949 Mach, an asteroid

- Mach, a lunar crater

- Mach bands, an optical illusion

- Mach diamonds, seen in supersonic exhausts

- Mach Five, the car used by Speed Racer

- Mach number, the unit for speed relative to the speed of sound

Bibliography

- Mach, Ernst (1873). Optisch-akustische Versuche (in German). Praha: Calve.

- Mach, Ernst (1900). Principien der Wärmelehre (in German). Leipzig: Johann Ambrosius Barth.

- Mach, Ernst (1903). Analyse der Empfindungen und das Verhältnis des Physischen zum Psychischen (in Italian). Torino: Fratelli Bocca.

- Mach, Ernst (1904). Mechanik in ihrer Entwicklung historisch-kritisch dargestellt (in French). Paris: Librairie scientifique Hermann et C.ie.

- Mach, Ernst (1908). Erkenntnis und Irrtum (in French). Paris: Flammarion.

Mach's principal works in English:

- The Science of Mechanics. Translated by McCormack, Thomas J. (4th ed.). Chicago: The Open Court Publishing Co. 1919 [1883].

- "Photographische Fixirung der durch Projectile in der Luft eingeleiteten Vorgänge". Sitzungsber. Kaiserl. Akad. Wiss., Wien, Math.-Naturwiss. Cl. (in German). 95 (Abt. II): 764–780. 1887. Bibcode:1887AnP...268..277M. doi:10.1002/andp.18872681008. with Peter Slacher

- Williams, C.W., ed. (1897). "The Analysis of Sensations". Contributions to the Analysis of Sensation (1st ed.). Chicago: Open Court Publishing Company.

- Popular Scientific Lectures (1895); Revised & enlarged 3rd edition (1898)

- "Space and Geometry from the Point of View of Physical Inquiry". Monist. 14 (1): 1–32. 1903. doi:10.5840/monist190314139. ISSN 0026-9662. with S.J.B. Sugden

- History and Root of the Principle of the Conservation of Energy (1911)

- The Principles of Physical Optics (1926)

- Knowledge and Error (1976)

- Principles of the Theory of Heat (1986)

- Fundamentals of the Theory of Movement Perception (2001)

See also

References

Notes

- On this interdependency of Mach's physics, physiology, history and philosophy of science see Blackmore 1972, Blackmore (ed.) 1992 and Hentschel 1985 against Paul Feyerabend's efforts to decouple these three strands.

- On Mach's historiography, cf., e.g., Hentschel 1988 on his impact in Vienna, see Stadler et al. (1988), and Blackmore et al. (2001).

- Selections are taken from his essay The Economical Nature of Physical Inquiry, excerpted by Kockelmans and slightly corrected by Blackmore. (citation below).

- Barbour 2001, p. 220 states "In the Machian view, the properties of the system are exhausted by the masses of the particles and their separations, but the separations are mutual properties. Apart from the masses, the particles have no attributes that are exclusively their own. They — in the form of a triangle — are a single thing. In the Newtonian view, the particles exist in absolute space and time. These external elements lend the particles attributes — position, momentum, angular momentum — denied in the Machian view. The particles become three things. Absolute space and time are an essential part of atomism".

- The preface of the posthumously published Principles of Physical Optics explicitly rejects Einstein's relativistic views but it has been argued that the text is inauthentic.(Wolters 2012, pp. 39–57)

Citations

- Mach 1919, p. 227.

- "Ernst Mach". Encyclopædia Britannica. 2016. Retrieved 6 January 2016.

- Blackmore 1972.

- Sonnert 2005, p. 221.

- Cohen & Seeger 1975, p. 158: And Mach, in personal conviction, was a socialist and an atheist.

- Baatz 1992, pp. 183–199.

- Blackmore 1972, p. 293, Chapter 18 – Mach and Buddhism: Mach was logically a Buddhist and illogically a believer in science.

- Reichenbach, H (January 1983). "Contributions of Ernst Mach to Fluid Mechanics". Annual Review of Fluid Mechanics. 15 (1): 1–29. Bibcode:1983AnRFM..15....1R. doi:10.1146/annurev.fl.15.010183.000245. ISSN 0066-4189. Retrieved 23 February 2023.

- Anderson 1998, p. 65, Chapter 3.

- Yourgrau 2005.

- Mach & Salcher 1887, pp. 764–780.

- Scott 2003.

- Steila 2013.

- Lenin 1909.

- Bunnin & Yu 2008, p. 405.

- Penrose 2016, p. 753: Mach's principle asserts that physics should be defined entirely in terms of the relation of one body to another, and that the very notion of a background space should be abandoned

- Mach 1919: [The] investigator must feel the need of ... knowledge of the immediate connections, say, of the masses of the universe. There will hover before him as an ideal insight into the principles of the whole matter, from which accelerated and inertial motions will result in the same way.

- Pais 2005, p. 283.

- Riegler 2011, pp. 235–255.

- Hawkins & Schacht 2005.

- Ratliff 1975.

- Ratliff 1965.

- Sugden & Mach 1903.

- Chiesa 1994.

Sources

- Anderson, J. (1998), Mack, Pamela E. (ed.), "Research in Supersonic Flight and the Breaking of the Sound Barrier", From Engineering Science to Big Science: The NACA and NASA Collier Trophy Research Project Winners, NASA

- Barbour, Julian (2001). The End of Time: The Next Revolution in Physics. USA: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-514592-2.

- Baatz, Ursula (1992). "Ernst Mach - the Scientist as a Buddhist ?". In Blackmore, J.T. (ed.). Ernst Mach — A Deeper Look. Dordrecht: Springer. pp. 183–199. doi:10.1007/978-94-011-2771-4_9. ISBN 978-0-7923-1853-8.

- Blackmore, John T. (1972). Ernst Mach. His Life, Work, and Influence. Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press. ISBN 9780520018495. OCLC 534406. OL 4466579M.

- Bunnin, Nicholas; Yu, Jiyuan (2008). "Mach, Ernst (1838-1916)". The Blackwell Dictionary of Western Philosophy. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-0-470-99721-5.

- Chiesa, Mecca (1994). Radical Behaviorism: The Philosophy and the Science. Authors Cooperative. ISBN 978-0-9623311-4-5.

- Cohen, Robert S.; Seeger, Raymond J. (1975). Ernst Mach: Physicist and Philosopher. Dordrecht: Springer. ISBN 90-277-0016-8.

- Hawkins, J.E.; Schacht, J. (12 April 2005). "Sketches of Otohistory - Part 8:The Emergence of Vestibular Science" (PDF). Audiology and Neurotology. 10 (4): 185–190. doi:10.1159/000085076. PMID 15832015. S2CID 30875633. Archived from the original (PDF) on 21 July 2011.

- Heinzmann, Gerhard; Stump, David (10 October 2017), "Henri Poincaré", Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy

- Hentschel, Klaus (1985). "On Feyerabend's version of 'Mach's theory of research and its relation to Einstein'". Studies in History and Philosophy of Science Part A. 16 (4): 387–394. Bibcode:1985SHPSA..16..387H. doi:10.1016/0039-3681(85)90019-6. ISSN 0039-3681.

- Hentschel, Klaus (1988). "Die Korrespondenz Duhem-Mach: Zur 'Modellbeladenheit' von Wissenschaftsgeschichte". Annals of Science. 45 (1): 73–91. doi:10.1080/00033798800200121. ISSN 0003-3790.

- Lenin, V.I. (1909), Materialism and Empirio-criticism: Critical Comments on a Reactionary Philosophy

- Mehra, Jagdish; Rechenberg, Helmut (2001). The Historical Development of Quantum Theory. Springer. ISBN 978-0-387-95180-5.

- Pais, Abraham (2005). Subtle is the Lord: The Science and the Life of Albert Einstein. Oxford: OUP. p. 283. ISBN 978-0-19-280672-7.

- Penrose, Roger (2016). The Road to Reality: A Complete Guide to the Laws of the Universe. Random House. ISBN 978-1-4464-1820-8.

- Pojman, Paul (21 May 2008). "Ernst Mach". Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Retrieved 19 August 2019.

- Ratliff, Floyd (1965). Mach bands: quantitative studies on neural networks in the retina. Holden-Day.

- Ratliff, Floyd (1975). "On Mach's Contributions to the Analysis of Sensations". In Seeger, Raymond J.; Cohen, Robert S. (eds.). Ernst Mach, Physicist and Philosopher.

- Riegler, Alexander (2011). "Constructivism". In Luciano L'Abate (ed.). Paradigms in Theory Construction. Springer. pp. 235–255. doi:10.1007/978-1-4614-0914-4_13. ISBN 978-1-4614-0914-4.

- Scott, Jeff (9 November 2003). "Ernst Mach and Mach Number". Aerospaceweb.org. Retrieved 24 October 2015.

- Sonnert, Gerhard (2005). Einstein and Culture (illustrated ed.). Humanity Books. ISBN 978-1-59102-316-6.

- Steila, Daniela (2013). Nauka i revoljucija. Recepciia empiriokriticizma v russkoi kul'ture (1877-1910 gg.) [Science and revolution. Reception of empiriocriticism in Russian culture] (in Croatian). Moscow: Akademicheskii Proekt. hdl:2318/141997.

- Wolters, Gereon (2012). "Mach and Einstein, or Clearing Troubled Waters in the History of Science". In Lehner, Christoph; Renn, Jürgen; Schemmel, Matthias (eds.). Einstein and the Changing Worldviews of Physics. Boston: Springer – Birkhäuser. ISBN 978-0-8176-4940-1.

- Yourgrau, Palle (2005). A World Without Time: The Forgotten Legacy of Gödel and Einstein. Allen Lane. ISBN 978-0-7139-9387-5.

Further reading

- Erik C. Banks: Ernst Mach's World Elements. A Study in Natural Philosophy. Dordrecht: Kluwer (now Springer), 2013.

- John Blackmore and Klaus Hentschel (eds.): Ernst Mach als Außenseiter. Vienna: Braumüller, 1985 (with select correspondence).

- Blackmore, J.T.; Itagaki, R.; Tanaka, Satoru, eds. (2001). Ernst Mach's Vienna 1895–1930: Or Phenomenalism as Philosophy of Science. Dordrecht: Springer. ISBN 978-0-7923-7122-9.

- John T. Blackmore, Ryoichi Itagaki and Setsuko Tanaka (eds.): Ernst Mach's Science. Kanagawa: Tokai University Press, 2006.

- John T. Blackmore, Ryoichi Itagaki and Setsuko Tanaka: Ernst Mach's Influence Spreads. Bethesda: Sentinel Open Press, 2009.

- John T. Blackmore, Ryoichi Itagaki and Setsuko Tanaka: Ernst Mach's Graz (1864–1867), where much science and philosophy were developed. Bethesda: Sentinel Open Press, 2010.

- John T. Blackmore: Ernst Mach's Prague 1867–1895 as a human adventure, Bethesda: Sentinel Open Press, 2010.

- Everdell, William (1997). The First Moderns. Profiles in the Origins of Twentieth-Century Thought. University of Chicago Press.

- Haller, Rudolf; Stadler, Friedrich, eds. (1988). Ernst Mach – Werk und Wirkung (in German). Vienna: Hoelder-Pichler-Tempsky.

- Hentschel, Klaus (2013). "Ernst Mach". In Hessenbruch, Arne (ed.). Reader's Guide to the History of Science. London: Routledge. ISBN 978-1-134-26301-1 – via Taylor and Francis.

- Hoffmann, D.; Laitko, H., eds. (1991). Ernst Mach – Studien und Dokumente (in German). Berlin.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Kockelmans, Joseph J. (1968). Philosophy of science. The historical background. New York: The Free Press.

- Prosser, V.; Folta, J., eds. (1991), Ernst Mach and the development of Physics – Conference Papers, Prague: Universitas Carolina Pragensis

- Thiele, Joachim (1978), Wissenschaftliche Kommunikation – Die Korrespondenz Ernst Machs (in German), Kastellaun: Hain (with select correspondence).

External links

- Ernst Mach bibliography of all of his papers and books from 1860 to 1916, compiled by Vienna lecturer Dr. Peter Mahr in 2016

- Various Ernst Mach links, compiled by Greg C Elvers

- Klaus Hentschel: Mach, Ernst, in: Neue Deutsche Biographie 15 (1987), pp. 605–609.

- Works by Ernst Mach at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about Ernst Mach at Internet Archive

- Works by Ernst Mach at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

- Pojman, Paul. "Ernst Mach". In Zalta, Edward N. (ed.). Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

- Short biography and bibliography in the Virtual Laboratory of the Max Planck Institute for the History of Science

- Ernst Mach: The Analysis of Sensations (1897) [translation of Beiträge zur Analyse der Empfindungen (1886)]

- Ernst Mach at the Mathematics Genealogy Project

- "The critical positivism of Mach and Avenarius": entry in the Britannica Online Encyclopedia