The Anderson Tapes

The Anderson Tapes is a 1971 American crime film directed by Sidney Lumet and starring Sean Connery and featuring Dyan Cannon, Martin Balsam and Alan King. The screenplay was written by Frank Pierson, based upon a best-selling 1970 novel of the same name by Lawrence Sanders. The film is scored by Quincy Jones and marks the feature film debut of Christopher Walken.

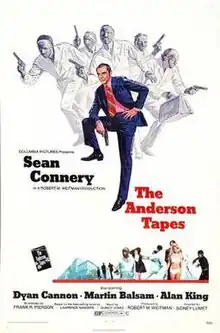

| The Anderson Tapes | |

|---|---|

original film poster | |

| Directed by | Sidney Lumet |

| Screenplay by | Frank Pierson |

| Based on | The Anderson Tapes by Lawrence Sanders |

| Produced by | Robert M. Weitman |

| Starring | |

| Cinematography | Arthur J. Ornitz |

| Edited by | Joanne Burke |

| Music by | Quincy Jones |

Production company | Robert M. Weitman Productions |

| Distributed by | Columbia Pictures |

Release date |

|

Running time | 99 minutes |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $3 million |

| Box office | $5 million (US/Canada)[1] |

It was the first major film to focus on the pervasiveness of electronic surveillance, from security cameras in public places to hidden recording devices.[2]

Plot

Safe-cracker John "Duke" Anderson is released after ten years in prison. He renews his relationship with his old girlfriend, Ingrid. She lives in an upper-class apartment block in Manhattan. Anderson almost instantly decides to burgle the entire building in a single sweep – filling a furniture van with the proceeds. He gains financing from a nostalgic Mafia boss and gathers his four-man crew. Also included is an old ex-con drunk, "Pop", whom Anderson met in jail, and who is to play concierge while the real one is bound and gagged in the cellar.

Less welcome is a man the Mafia foists onto Anderson – the thuggish "Socks". Socks is a psychopath who has become a liability to the mob and, as part of the deal, Anderson must kill him in the course of the robbery. Anderson is not keen on this, since the operation is complicated enough, but is forced to go along.

Anderson has unwittingly entered a world of pervasive surveillance – the agents, cameras, bugs, and tracking devices of numerous public and private agencies see almost the entire operation from the earliest planning to the execution. As Anderson advances the scheme, he moves from the surveillance of one group to another as locations or individuals change. These include a private detective hired by the wealthy Werner to eavesdrop on his mistress Ingrid, who happens to be Anderson's girlfriend; the BNDD, who are checking over a released drug dealer; the FBI, investigating Black activists and the interstate smuggling of antiques; and the IRS, which is after the mob boss who is financing the operation. Yet, because the various federal, state and city agencies performing the surveillance are all after different goals, none of them is able to "connect the dots" and anticipate the robbery.

The operation proceeds over a Labor Day weekend. Disguised as a Mayflower moving and storage crew, the crooks cut telephone and alarm wires and move up through the building, gathering the residents as they go and robbing each apartment.

Jimmy, the son of two of the residents, is a paraplegic and asthmatic who is left behind in his air-conditioned room. Using his amateur radio equipment, he calls up other radio amateurs, based in other states, who contact the police. The alarm is thus raised, but only after resolving which side (callers or emergency services) should take the phone bill.

As the oblivious criminals work, the police array enormous forces outside to prevent their escape and send a team in via a neighboring rooftop.

In the shootout that follows, Anderson kills Socks, but is himself shot by the police. The other robbers are killed, injured or captured. Pop gives himself up while covering for the others by putting all the blame on Socks. Having never adapted to life on the outside, he looks forward to going back to prison.

In the course of searching the building, the police discover some audio listening equipment left behind by the private detective who was hired to check up on Ingrid and track it to find Anderson in critical condition after having tried to escape. To avoid embarrassment over the failure to discover the robbery despite having Anderson on tape in several surveillance operations, and since many of the recordings were illegal, each of the agencies orders its tapes to be erased.

Cast

- Sean Connery as Duke Anderson

- Dyan Cannon as Ingrid

- Martin Balsam as Haskins

- Ralph Meeker as Delaney

- Alan King as Pat Angelo

- Dick Anthony Williams as Spencer

- Val Avery as "Socks" Parelli

- Garrett Morris as Officer Everson

- Stan Gottlieb as Pop

- Christopher Walken as The Kid

- Conrad Bain as Dr. Rubicoff

- Margaret Hamilton as Miss Kaler

- Anthony Holland as Psychologist

- Scott Jacoby as Jerry Bingham

- Judith Lowry as Mrs. Hathaway

- Meg Myles as Mrs. Longene (as Meg Miles)

- Norman Rose as Longene

- Max Showalter as Bingham

- Janet Ward as Mrs. Bingham

- Paul Benjamin as Jimmy

- Richard Shull as Werner

Cast notes

- This was the first major motion picture for Christopher Walken, as well as the last on-screen film appearance by Margaret Hamilton.[2]

- Sean Connery, Martin Balsam, and director Sidney Lumet were to work together again on Murder on the Orient Express. Connery had previously worked with the director on The Hill, and they would reunite the following year on The Offence, and again many years later for Family Business. Balsam and Lumet had worked together previously on 12 Angry Men.

- Two characters from the novel on which the film was based were merged for the film: "Ingrid Macht" and "Agnes Everleigh" became "Ingrid Everleigh".[3]

- Sean Connery's performance as the likeable criminal Duke Anderson was instrumental in his breakout from being typecast as James Bond. It also restored him to the ranks of top male actors in the United States.[2]

Production

The Anderson Tapes was filmed on location in New York City on Fifth Avenue at the Convent of the Sacred Heart (the luxury apartment building), Rikers Island Prison, the Port Authority Bus Terminal, Luxor Health Club and on the Lower East Side. Interiors scenes were filmed at Hi Brown Studio[4] and ABC-Pathé Studio, both in New York City.[3] The production was on a tight budget, and filming was completed from mid-August to October 16, 1970.[2] The film was the first for producer Robert M. Weitman as an independent producer.[3]

Columbia Pictures was not happy with the concept for the ending of the film, in which Connery escaped to be pursued by police helicopters, fearing that it would hurt sales to television, which generally required that bad deeds do not go unpunished.[2]

The Anderson Tapes made its U.S. network television premiere on September 11, 1972, as an installment of NBC Monday Night at the Movies.[5]

Box office and critical response

The film generated $5 million in U.S. and Canada rentals.

Roger Greenspun of The New York Times called The Anderson Tapes "well done and entertaining". He noted Lumet's direction by writing "The quality of professionalism appears in rather lovely manifestations to raise a by no means perfect film to a level of intelligent efficiency that is not so very far beneath the reach of art".[6] Roger Ebert enjoyed the film but called Lumet's emphasis on electronic surveillance a "serious structural flaw".[7] Andrew Sarris of The Village Voice wrote that there was only "eleven good minutes in it", calling the rest of the film "confused and uncertain".[8]

See also

References

- "All-time Film Rental Champs". Variety. January 7, 1976. p. 48.

- Soares, Emily. "The Anderson Tapes (1971) | Articles". TCM.com.

- "The Anderson Tapes (1971) | Notes". TCM.com.

- Allman, Richard (2005). New York: The Movie Lover's Guide. New York: Harper & Row. ISBN 0-7679-1634-4.

- Jay, Robert (November 29, 2009). "Nielsen Top Ten, September 11th - September 17th, 1972". Television Obscurities. Retrieved August 24, 2018.

- Greenspun, Roger (June 18, 1971). "The Screen; 'The Anderson Tapes' Stars Connery". The New York Times.

- Ebert, Roger (June 30, 1971). "Anderson Tapes movie review & film summary (1971)". RogerEbert.com.

- Sarris, Andrew (July 22, 1971). "films in focus". The Village Voice. p. 55 – via Google News Archive.