The Astonished Heart

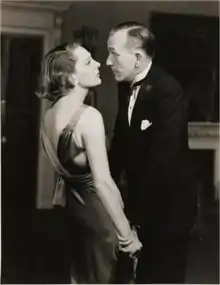

The Astonished Heart, described by the author as "a tragedy in six scenes", is a short play by Noël Coward, one of ten that make up Tonight at 8.30, a cycle written to be performed across three evenings. One-act plays were unfashionable in the 1920s and 30s, but Coward was fond of the genre and conceived the idea of a set of short pieces to be played across several evenings. The actress most closely associated with him was Gertrude Lawrence, and he wrote the plays as vehicles for them both.

The Astonished Heart depicts a leading psychiatrist falling passionately in love with an old friend of his wife. She has wilfully led him on but is unprepared for the disastrous effect on him. Increasingly desperate, he watches his own mind lose control of itself, and he finally kills himself. The title is taken from Deuteronomy: "the Lord shall smite thee with madness and blindness and astonishment of heart".

The cycle was first produced in 1935 in Manchester and then toured for nine weeks before opening in London (1936) and New York (1936–37).[n 1] It has been revived occasionally and has been adapted for film, television and radio.

Background and first productions

Short plays had been popular in the previous century, often as curtain-raisers and afterpieces to longer plays. By the 1920s they had gone out of fashion, but Coward was fond of the genre and wrote several early in his career.[2] He wrote, "A short play, having a great advantage over a long one in that it can sustain a mood without technical creaking or over padding, deserves a better fate, and if, by careful writing, acting and producing I can do a little towards reinstating it in its rightful pride, I shall have achieved one of my more sentimental ambitions."[3] In 1935 he conceived the idea of a set of short plays, to run in varying permutations on three consecutive nights at the theatre. His biographer Philip Hoare describes it as "a bold idea, risky and innovative".[4] Coward finished writing all ten of the plays by the end of August 1935.[5]

The actress most closely associated with Coward was Gertrude Lawrence, his oldest friend, with whom he had first acted as a child in Hannele in 1913.[6] They starred together in his revue London Calling! (1923) and his comedy Private Lives (1930–31),[7] and he wrote the Tonight at 8.30 plays "as acting, singing and dancing vehicles for Gertrude Lawrence and myself".[8] Coward directed the plays as well as acting in them. They were performed in various combinations of three.[n 2] Coward loved playing in some of the other plays in Tonight at 8.30, particularly Fumed Oak and Red Peppers, but "I hated playing The Astonished Heart. It depressed me."[10]

The Astonished Heart was first presented on 15 October 1935 at the Opera House, Manchester, the second play in a programme that began with We Were Dancing and ended with Red Peppers.[11] The first London performance was on 9 January 1936 at the Phoenix Theatre.[12] The cycle played to full houses, and the limited season closed on 20 June, after 157 performances.[13][n 3] The Broadway premiere was at the National Theatre on 27 November 1936, with mostly the same cast as in London. As in Manchester, the programme also included We Were Dancing and Red Peppers.[16] The New York run of the cycle, a limited season, as in London, ended prematurely because Coward was taken ill.[n 4]

Roles and original cast

- Barbara Faber – Alison Leggatt (Joyce Carey in New York)

- Christian Faber – Noël Coward

- Leonora Vail – Gertrude Lawrence

- Tim Verney – Anthony Pelissier

- Susan Birch – Everley Gregg (Joan Swinstead in New York)

- Ernest – Edward Underdown

- Sir Reginald French – Alan Webb

Plot

The first scene is set in the London flat of Chris and Barbara Faber, in November 1935. Along with Chris's secretary, Susan, and his assistant, Tim, Barbara is waiting for the arrival of Leonora Vail. Sir Reginald French, a surgeon, enters from a bedroom, asking if Leonora has come yet. Barbara asks, "There isn't much time, is there?" The doctor replies that he fears not, and that his patient is asking for Leonora in his moments of consciousness. The doorbell rings. Barbara comments "It's the same – exactly the same as a year ago ... the first time she ever came into this room". Ernest, the butler announces Mrs Vail; the lights fade and come up again on the second scene, which is a flashback to November 1934.

Barbara, Tim, Susan and Ernest are all in the same positions, though with minor changes of costume. Leonora, an old school friend of Barbara, enters. When Chris looks in for a few moments, his manner to Leonora is vague and uninterested. Leonora tells Barbara that she much prefers his nice assistant, Tim. She leaves, after inviting Barbara, Tim and Chris ("if he'll come") to lunch. Tim comes in, looking for a Bible: Chris wants a quotation for his next lecture on psychopathology. They borrow the cook's Bible and find the passage he wants: "The Lord shall smite thee with madness, and blindness, and astonishment of the heart."

In the third scene, two months later, Chris and Leonora have become considerably more intimate: they are kissing each other passionately. Leonora confesses that she has deliberately tried to make him fall in love, in revenge for his dismissive manner at their first meeting. He admits that he was deliberately rude to her at first because "You irritated me, you were so conscious of how beautiful you looked". He adds that despite his affair with Leonora he loves Barbara "deeply and truly and for ever". The scene ends with another passionate clinch.

Three months later, scene four takes place on an early April morning. Barbara has been sitting up all night, waiting for Chris to come home. She greets him calmly but insists on some straight talking. She tells him that his increasingly unhinged mental state, brought on by the strain of his affair, is affecting his work and his life. She says he should go away with Leonora for two or three months, leaving Tim to run the practice. In the fifth scene, in November, Chris and Leonora quarrel bitterly. She says she is leaving him. He throws her to the floor. After she picks herself up and leaves, he drinks two glasses of whisky, goes to the window and jumps out.

The final scene is a continuation of the first. Ernest announces: "Mrs Vail." Barbara gives her a quick drink and sends her straight into the bedroom. The others wait, talking distractedly, until she comes back. Barbara asks, "Is he – ?" Leonora replies, "Yes. ... He didn't know me; he thought I was you; he said – 'Baba, I'm not submerged any more' – and then he said 'Baba' again – and then – then he died." She leaves the room as the curtain falls.

- Source: Play text and Mander and Mitchenson.[19]

Revivals and adaptations

Theatre

In 1937 a company headed by Estelle Winwood and Robert Henderson toured the Tonight at 8.30 cycle in the US and Canada. In their production of The Astonished Heart Helen Chandler played Leonora, Winwood played Barbara and Bramwell Fletcher was Chris.[20]

At the Chichester Festival in 2006 The Astonished Heart was staged, as were five other plays from the cycle.[n 5] Josefina Gabrielle and Alexander Hanson played the leading roles.[21] The Antaeus Company in Los Angeles revived all ten plays in October 2007,[22] and in 2009 the Shaw Festival did likewise.[23] In the first professional revival of the cycle in Britain,[n 6] given by English Touring Theatre in 2014, Shereen Martin played Leonora, Olivia Poulet was Barbara and Orlando Wells played Chris.[24] In London, nine of the ten plays in the cycle were given at the Jermyn Street Theatre in 2018.[n 7] In The Astonished Heart, the cast included Sara Crowe as Leonore, Miranda Foster as Barbara and Nick Waring as Chris.[25]

Radio and television

An adaptation for radio was broadcast by the BBC in the US in 1953 with Diana Churchill as Barbara, Brenda Dunrich as Leonora and David King-Wood as Chris.[26]

In 1991, BBC television mounted productions of the individual plays of Tonight at 8.30 starring Joan Collins.[27] As Leonora in The Astonished Heart she co-starred with John Alderton as Chris and Siân Phillips as Barbara.[28]

Cinema

A film adaptation was made of the play in 1949. Coward himself played Chris, Celia Johnson played Barbara and Margaret Leighton was Leonora.[29]

Critical reception

During the early productions, Punch praised Coward for compressing into "six brief scenes" material that "is still commonly thought to justify three Acts".[30] The Manchester Guardian thought "the plot interesting, the dialogue as lively as ever" but felt the play as a whole "suffers from unreality".[31] The Observer described The Astonished Heart as "a clever play which probably touched nobody's heart" ... "full of good stagecraft and good dialogue [but] power was lacking. … Tragedy and Mr Coward are still far apart".[32] The Times, too, thought that Coward had failed to achieve a true tragedy, "but the thing is courageous and not frivolous, not written to a popular formula".[33] The Saturday Review thought it "a perfect little drama … sublime".[34]

When The Astonished Heart was revived in a double-bill with Still Life in 2004, The Guardian's critic wrote, "The astonishing thing is that, stereotypical though they are in many ways, these little plays still have the power to destabilise all your expectations and make your heart turn over. It is as if their very familiarity allows them to creep up and take you by surprise. Maybe it is because Coward understood the heart so very well, and ensured that underneath the brittle surfaces of these pieces is a well of passion and desire".[35] In 2006, Benedict Nightingale wrote in The Times that The Astonished Heart, "memorably demonstrates the inadequacy of English reason and tolerance when faced with passion".[21] When the piece was revived in 2018, the reviewer in The Independent wrote, "The Astonished Heart offers a devastating post-mortem on the suicide of a celebrated psychiatrist whose patient, liberal wife cannot save him from toppling into a disastrous obsession with his mistress. … Parts of this are as lacerating as Strindberg".[36]

Notes, references and sources

Notes

- One of the ten plays, Star Chamber, was given one performance and immediately dropped; it is seldom revived, and throughout Coward's lifetime the published texts of the cycle omitted it.[1]

- The programme of plays chosen for each performance was advertised in advance.[9]

- The London run was interrupted by Lawrence's illness caused by overwork, as she was also shooting a film at the time. Coward, who disliked long runs, and also needed to set aside time to write and compose,[14] usually insisted on playing a part for no longer than six months: "preferably three months in New York and three months in London"[15]

- The play closed for a week at the beginning of March because Coward was unwell. It was announced that he was suffering from laryngitis,[17] but in fact it was a nervous breakdown, brought on by overwork.[18] The run resumed on 8 March, but after two performances Coward's doctor insisted that he withdraw completely, and the last Broadway performance was given on 9 March.[17]

- Hands Across the Sea, Red Peppers, Family Album, Fumed Oak and Shadow Play [21]

- Omitting Star Chamber.[24]

- The omitted play was Fumed Oak.[25]

References

- Morley (1999), p. xii

- Mander and Mitchenson, pp. 25–27 and 52

- Quoted in Morley (2005), p. 66

- Hoare, p. 268

- Morley (1974), p. 188; and Hoare, p. 269

- Hoare, pp. 27, 30 and 51

- Morley, (1999), p. viii; and Mander and Mitchenson, pp. 209 and 217

- Quoted in Mander and Mitchenson, p. 283

- "Phoenix Theatre", The Times, 20 January 1936, p. 10; 11 February 1936, p. 12; 2 March 1936, p. 12; 6 April 1936, p. 10; 2 May 1936, p. 12; 10 June 1936, p. 14.

- Castle, p. 139

- Mander and Mitchenson, p. 282

- "Phoenix Theatre", The Times, 19 January 1936, p. 15.

- Morley (1974), p. 192

- Morley (1974), pp. 94–95

- Hoare, p. 155

- Mander and Mitchenson, p. 283

- "Coward, Sick, Closes Plays at National", The Daily News, 11 March 1937, p. 119

- Morley (1974), p. 195

- Coward, pp. 7–11 (Scene 1); 11–22 (Scene 2); 22–27 (Scene 3); 28–35 (Scene 4); 36–41 (Scene 5) and 41–43 (Scene 6); and Mander and Mitchenson, pp. 291–293

- "Superb Acting in Fine Plays", The Vancouver Sun, 22 November 1937, p. 9

- Nightingale, Benedict. "A clutch of Coward gems", The Times, 28 July 2006, p. 34

- Morgan, Terry. "Tonight at 8:30", Variety, 5 November 2007

- Belcher, David. "Brushing Up Their Coward in Canada". The New York Times, 17 August 2009

- "Tonight at 8.30", British Theatre Guide. Retrieved 1 April 2020

- "Tonight at 8.30", Jermyn Street Theatre. Retrieved 1 April 2020

- " The Stars in Their Choices", BBC Genome. Retrieved 2 April 2020

- Truss, Lynne. "Tonight at 8.30", The Times, 15 April 1991

- "Television", The Times, 27 April 1991, p. 19

- Noël Coward website Archived 1 December 2008 at the Wayback Machine.

- Keown, Eric. "At the Play", Punch, 22 January 1936, p. 20

- "To-night at 7.30", The Manchester Guardian, 16 October 1935, p. 11

- "3 More Plays by Noel Coward", The Observer, 20 October 1935, p. 12

- "The Phoenix Theatre", The Times, 10 January 1936, p. 10

- "Theatre Notes", The Saturday Review, 18 January 1936, p. 95

- Gardner, Lynn. "Astonished Heart/Still Life, Playhouse, Liverpool", The Guardian, 26 March 2004

- Taylor, Paul. "Tonight at 8.30, Jermyn Street Theatre", The Independent, 23 April 2018 (subscription required)

Sources

- Castle, Charles (1972). Noël. London: W H Allen. ISBN 978-0-491-00534-0.

- Coward, Noël (1938). The Astonished Heart. London: French. OCLC 38032596.

- Hoare, Philip (1995). Noël Coward, A Biography. London: Sinclair-Stevenson. ISBN 978-1-4081-0675-4.

- Mander, Raymond; Joe Mitchenson (2000) [1957]. Theatrical Companion to Coward. Barry Day and Sheridan Morley (2000 edition, ed.) (second ed.). London: Oberon Books. ISBN 978-1-84002-054-0.

- Morley, Sheridan (1974) [1969]. A Talent to Amuse. London: Penguin. ISBN 978-0-14-003863-7.

- Morley, Sheridan (1999). "Introduction". Coward: Plays 7. London: Bloomsbury. ISBN 978-0-4137-3400-6.

- Morley, Sheridan (2005). Noël Coward. London: Haus Publishing. ISBN 978-1-90-434188-8.