The Building of the Boat

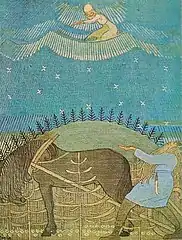

The Building of the Boat (in Finnish: Veneen luominen) was a projected Wagnerian opera for soloists, chorus, and orchestra that occupied the Finnish composer Jean Sibelius from 8 July 1893 to late-August 1894, at which point he abandoned the project. The piece was to have been a collaboration with the Finnish author J. H. Erkko, whose libretto (joint with Sibelius) adapted Runos VIII and XVI of the Kalevala, Finland's national epic. In the story, the wizard Väinämöinen tries to seduce the moon goddess Kuutar[lower-alpha 1] by building a boat with magic; his incantation is missing three words, and he journeys to the underworld of Tuonela to obtain them.

In July 1894, Sibelius attended Wagner festivals in Bayreuth and Munich. His enthusiasm for his own opera project waned as his attitude towards the German master turned ambivalent and, then, decisively hostile. Instead, Sibelius began to identify as a "tone painter" in the Lisztian mold, and subsequently reworked most of The Building of the Boat's material into 1895's The Wood Nymph (Op. 15) and 1896's The Lemminkäinen Suite (Op. 22)—most notably, the opera's overture evolved into The Swan of Tuonela. Sibelius never again attempted a large-scale opera, making it one of the few genres in which he did not produce a viable work.[lower-alpha 2]

History

From the 1870s to the 1890s, the politics of Finland featured a struggle between the Svecomans and the Fennomans. Whereas the former sought to preserve the privileged position of the Swedish language, the latter desired to promote Finnish as a means of inventing a distinctive national identity.[2][3] High on the "agenda" for the Fennomans was to develop vernacular opera, which they "understood as a symbol of a proper nation"; to do so, they would need a permanent company with an opera house and a Finnish-language repertoire at its disposal.[4] Swedish-speaking Helsinki already had a permanent theatre company housed at the Swedish Theatre, and thanks to Fredrik Pacius, two notable, Swedish-language operas: King Charles's Hunt (Kung Karls jakt, 1852) and The Princess of Cyprus (Princessan af Cypern, 1860).[5][6][lower-alpha 3] Success was hard-won: in 1872, the Fennoman Kaarlo Bergbom founded the Finnish Theatre Company, and a year later it named its singing branch the Finnish Opera Company. This was a small group that, without an opera house as residence, toured the country performing "the best of the foreign repertoire", albeit translated into Finnish. However, the Fennomans still remained without an opera written to a Finnish libretto, and in 1879 the Finnish Opera Company folded due to financial difficulties.[8]

Acting as a catalyst, in 1891 the Finnish Literature Society organized a competition that provided domestic composers with the following brief: submit before the end of 1896 a Finnish-language opera about Finland's history or mythology; the winning composer and librettist receive 2000 and 400 markka, respectively.[9] Sibelius had seemed an obvious candidate to inaugurate a new vernacular era, given his role in the 1890s as an artist at the center of the nationalist cause in Finland: first, he had married into an aristocratic family identified with the Finnish resistance;[10] second, he had joined the Päivälehti circle of liberal artists and writers;[11] and third, he had become the darling of the Fennomans with his Finnish-language masterpiece Kullervo, a setting of The Kalevala for soloists, male choir, and orchestra.[12] The competition was the "initial impulse" for The Building of the Boat, the 1893–1894 project in which Sibelius had aspired to write a mythological, Finnish-language Gesamtkunstwerk on the subject of Väinämöinen. But Sibelius's opera foundered on the shoals of self-doubt and artistic evolution.[13] In the end, the Society received no submissions,[14] and when Sibelius finally emerged with his first opera, it was 1896's The Maiden in the Tower to a Swedish libretto.

Notes, references, and sources

Notes

- One of the liberties Sibelius appears to have taken with the libretto is to have altered the female character to whom Väinämöinen proposes. In the Kalevala, he attempts to seduce the Maiden of Pohjola, who is a daughter of the villainess Louhi. Kuutar, a different character, is instead the goddess of the moon. In his 8 July 1893 letter to J. H. Erkko, Sibelius specifically proposes: "... on [Väinämöinen's] journey away from the gloomy land of Pohja. Dusk approaches and the sky reddens. Kuutar, the daughter of the Moon, is discovered on a bank of clouds, singing as she weaves. Väinö falls hopelessly in love with her and pleads for her hand. She promises to be his if he can turn the splinters from her spindle into a boat by his song".[1]

- Sibelius's only completed opera is 1896's one-act (and relatively small-scale, with a duration of about 35 minutes) The Maiden in the Tower (Jungfrun i tornet, JS 101), which Sibelius withdrew after three performances.

- A third Swedish-language opera is The Junker's Guardian (Junkerns förmyndare), written in 1853 by the Finnish composer Axel Gabriel Ingelius. However, it was never performed and only partially survives. Finally, in 1887, Fredrik Pacius composed his final opera, Loreley (Die Loreley), to a German-language libretto.[7]

References

- Tawaststjerna 2008, pp. 141–142.

- Hannikainen 2018, pp. 116–118.

- Goss 2009, pp. 39, 117, 135–136, 144, 192.

- Hautsalo 2015, pp. 181, 185.

- Hautsalo 2015, p. 181.

- Korhonen 2007, pp. 25–26.

- Korhonen 2007, p. 26.

- Hautsalo 2015, pp. 175, 182.

- Päivälehti, No. 274 1891, p. 4.

- Tawaststjerna 2008, pp. 42–43.

- Tawaststjerna 2008, pp. 29–30.

- Tawaststjerna 2008, pp. 100, 102–103, 106.

- Tawaststjerna 2008, pp. 141–143, 158–160.

- Ketomäki 2017, pp. 271–272.

Sources

- Goss, Glenda Dawn (2009). Sibelius: A Composer's Life and the Awakening of Finland. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-226-00547-8.

- Hannikainen, Tuomas [in Finnish] (2018). Neito tornissa: Sibelius näyttämöllä [The Maiden in the Tower: Sibelius on Stage] (D.Mus) (in Finnish). Helsinki: Sibelius Academy, the University of the Arts Helsinki. ISBN 978-9-523-29103-4.

- Hautsalo, Liisamaija (2015). "Strategic Nationalism Towards the Imagined Community: The Rise and Success Story of Finnish Opera". In Belina-Johnson, Anastasia; Scott, Derek (eds.). The Business of Opera. London: Routledge. pp. 191–210. ISBN 978-1-315-61426-7.

- Ketomäki, Hannele (2017). "The Premiere of Pohjan neiti at the Vyborg Song Festival, 1908". In Kauppala, Anne; Broman-Kananen, Ulla-Britta; Hesselager, Jens (eds.). Tracing Operatic Performances in the Long Nineteenth Century: Practices, Performers, Peripheries. Helsinki: Sibelius Academy. pp. 269–288. ISBN 978-9-523-29090-7.

- Korhonen, Kimmo [in Finnish] (2007) [2003]. Inventing Finnish Music: Contemporary Composers from Medieval to Modern. Translated by Mäntyjärvi, Jaakko [in Finnish] (2nd ed.). Jyväskylä, Finland: Finnish Music Information Center (FIMIC) & Gummerus Kirjapaino Oy. ISBN 978-9-525-07661-5.

- Tawaststjerna, Erik (2008) [1965/1967; trans. 1976]. Sibelius: Volume I, 1865–1905. Translated by Layton, Robert. London: Faber and Faber. ISBN 978-0-571-24772-1.

- "Kilpapalkinto Suomalaista oopperaa varten" [Competition prize for a Finnish opera]. Päivälehti (in Finnish). No. 274. 25 November 1891. p. 4.

Further reading

- Barnett, Andrew (2007). Sibelius. New Haven, Connecticut: Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-16397-1.