The Candidate (1972 film)

The Candidate is a 1972 American political comedy-drama film starring Robert Redford and Peter Boyle, and directed by Michael Ritchie. The Academy Award–winning screenplay, which examines the various facets and machinations involved in political campaigns, was written by Jeremy Larner, a speechwriter for Senator Eugene J. McCarthy during McCarthy's campaign for the 1968 Democratic presidential nomination.

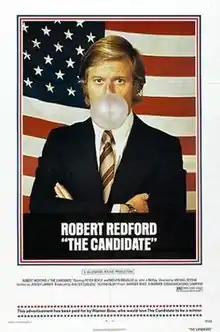

| The Candidate | |

|---|---|

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Michael Ritchie |

| Written by | Jeremy Larner |

| Produced by | Walter Coblenz |

| Starring | |

| Cinematography | |

| Edited by | |

| Music by | John Rubinstein |

| Distributed by | Warner Bros. |

Release date |

|

Running time | 109 minutes |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $1.6 million[1] |

| Box office | $2.5 million (U.S. and Canada rentals)[2] |

Plot

Marvin Lucas (Peter Boyle), a political election specialist, must find a Democratic candidate to oppose three-term California Senator Crocker Jarmon (Don Porter), a popular Republican. With no big-name Democrat eager to enter the unwinnable race, Lucas seeks out Bill McKay (Robert Redford), the idealistic, handsome, and charismatic son of former California governor John J. McKay (Melvyn Douglas).

Lucas gives McKay a proposition: since Jarmon cannot lose and the race is already decided, McKay is free to campaign saying exactly what he wants. McKay accepts in order to have the chance to spread his values, and hits the trail. With no serious Democratic opposition, McKay cruises to the nomination on his name alone. Lucas then has distressing news: according to the latest election projections, McKay will be defeated by an overwhelming margin. Lucas says the party expected McKay to lose but not to be humiliated, so he moderates his message to appeal to a broader range of voters.

McKay campaigns across the state, his message growing more generic each day. This approach lifts him in the opinion polls, but he has a new problem: because McKay's father has stayed out of the race, the media interpret his silence as an endorsement of Jarmon. McKay grudgingly meets his father and tells him the problem, and the elder McKay tells the media he is simply honoring his son's wishes to stay out of the race.

With McKay only nine points down in the polls, Jarmon proposes a debate. McKay agrees to give answers tailored by Lucas, but just as the debate is ending, McKay has a pang of conscience and blurts out that the debate has not addressed real issues such as poverty and race relations. Lucas is furious, as this will hurt the campaign. The media try to confront McKay backstage, but arrive as his father congratulates him on the debate; instead of reporting on McKay's outburst, the story becomes the reemergence of the former governor to help his son. The positive story, coupled with McKay's father's help on the trail, further closes the polling gap.

With the election a few days away, Lucas and McKay's father set up a meet-and-greet with a labor union representative to discuss another possible endorsement. During the meeting, the union representative tells McKay that he feels that they can do a lot of good for each other if they work together. McKay ostensibly tells him that he is not interested in associating with him, but the tension is quelled with uncomfortable yet unanimous laughter. After a publicized endorsement with the union rep, and with Californian workers now behind him, McKay pulls into a virtual tie.

McKay wins the election. In the final scene, he escapes the victory party and pulls Lucas into a room while throngs of journalists clamor outside. McKay asks Lucas, "What do we do now?" The media throng arrives to drag them out, and McKay never receives an answer.

Cast

- Robert Redford as Bill McKay

- Peter Boyle as Marvin Lucas

- Melvyn Douglas as former Governor John J. McKay

- Don Porter as Senator Crocker Jarmon

- Allen Garfield as Howard Klein

- Karen Carlson as Nancy McKay

- Quinn Redeker as Rich Jenkin

- Morgan Upton as Wally Henderson

- Michael Lerner as Paul Corliss

- Kenneth Tobey as Floyd J. Starkey

- Christopher Pray as David

- Joe Miksak as Neil Atkinson

- Jenny Sullivan as Lynn

- Tom Dahlgren as The pilot

- Gerald Hiken as the station manager

- Leslie Allen as Mabel

- Mike Barnicle as Wilson

- Broderick Crawford as Commercial Narrator (uncredited)

- George McGovern as himself

- Howard K. Smith as himself

- Hubert Humphrey as himself

- Van Amberg as himself

- Alan Cranston as himself

- John V. Tunney as himself

- Terry McGovern as himself

- Natalie Wood as herself

- Sam Yorty as himself

- Jesse M. Unruh as himself

- Bill Stout as himself

Production

Robert Redford said that the film was made as "a labour of love" and was shot inexpensively and quickly.[3] Redford and Ritchie had approached perhaps ten scriptwriters before offering the job to Jeremy Larner, who was under pressure to work quickly so the film would be out in time for the 1972 presidential election campaign; he had "about a month" to write the script, and wrote "exactly from noon to 3 a.m. every day"[4] Larner, having worked as a journalist and speechwriter, said his "experiences with various politicians came into the story; I used some stuff that was directly from the campaigns".[4] He also said that without the help he received from Robert Towne he would not have been able to complete the script.[5]

The character of McKay is based on U.S. Senator John V. Tunney (although he has similarities with Jerry Brown as well). Director Michael Ritchie worked for Tunney's successful campaign in the 1970 Senate election; campaign manager Nelson Rising was an associate producer on the film.[6][7] Rising, who went on to a successful career working in law, property development, and as a civic leader, as well as continuing his work in California politics, was - according to Larner - "instrumental in finding political locations in the Bay Area, and in supplying political volunteers for many of our campaign extras".[4] In the campaign, Tunney's media adviser had "bulls-eyed the young/old contrast" between Tunney and incumbent opponent George Murphy.[8]

Ritchie, Redford and writer Jeremy Larner spent the whole summer of 1971 putting together the script.[9] The scene where McKay is berated in a men's room is based on an incident that happened to presidential candidate Eugene McCarthy.[10] Larner said that "the moment when somebody hands McKay a Coke and a hot dog, so his hands are occupied, and then slugs him in the face—that really happened to McCarthy!".[4] The scriptwriter also recounted how he "wrote that character for Redford, obviously, and he told me at one point, “I can easily play a character stupider than myself. But I can’t be a bad guy—my public wouldn’t stand for it”".[4]

The character Howard Klein, played by Allen Garfield, was based on a New York political advertising consultant, David Garth, who Jeremy Larner met during the making of the movie, an encounter he described as "a big break".[4]

Redford was reunited with Natalie Wood who made a cameo appearance as herself, after she had semi-retired in 1970.[11] The two had co-starred in the 1965 film Inside Daisy Clover, as well as the 1966 film This Property Is Condemned.

Reception

The New York Times reviewer Vincent Canby called the film "one of the few good, truly funny American political comedies ever made," and commented that "The Candidate is serious, but its tone is coldly comic, as if it had been put together by people who had given up hope."[12] Variety called it "an excellent, topical drama" that was "directed and paced superbly," adding, "the entire film often seems like a documentary special in the best sense of the word."[13] Gene Siskel of the Chicago Tribune gave the film 3.5 stars out of 4 and praised Redford for a "winning performance."[14] Charles Champlin of the Los Angeles Times wrote that "Redford and Ritchie have teamed again to deliver what I think is nothing less than the best movie yet done about politics in coaxial America ... It has a right-now urgency that is strong and compelling."[15] Roger Ebert later said Ritchie "brought a sharply observant, almost documentary realism" to the film.[16]

Among negative reviews, Gary Arnold of The Washington Post panned the film as "a remarkably shallow, hypocritical attempt to satirize the American political process ... The problem with the filmmakers is that their disillusion is neither honestly felt nor dramatically demonstrated and earned. On the contrary, it seems merely a professional pose, a phony mask of invulnerability and moral superiority."[17] Penelope Gilliatt of The New Yorker called it a "dire film" with a "crass" script, and found Redford's resemblance to a Kennedy brother "merciless to watchers and unbelievably opportunistic on the part of the filmmakers; it is one of the most vulgar pieces of casting I can remember."[18] Robert Chappetta in Film Quarterly wrote that a serious flaw was that "Redford does poorly with the central dramatic element in the film: the changeover from being a reluctant candidate to wanting so badly to win that he is willing to compromise himself. Redford never conveys any real desire to win."[19] Richard Combs of The Monthly Film Bulletin wrote that "little definition or sympathy is lent McKay (who remains as much a cipher in the film's mechanics as he does in the hands of the political movers), and little interest generated in the workings of a system that is only conjured up in a gallery of intermittently familiar names and faces."[20]

Christopher Null, from filmcritic.com, gave the film 4.5/5, and said that "this satire on an American institution continues to gain relevance instead of lose it."[21]

The film holds a 'fresh' score of 89% on review aggregate Rotten Tomatoes, based on 35 critical reviews with the consensus: "The Candidate may not get all the details right when it comes to modern campaigning, but it captures political absurdity perfectly -- and boasts typically stellar work from Robert Redford to boot."[22]

Awards

The film won the Academy Award for Best Original Screenplay for Larner and was also nominated for Best Sound (Richard Portman and Gene Cantamessa).[23]

See also

References

- Ebert, Roger (January 19, 2003). "Redford Reflects On Indie Films, Political Climate". RogerEbert.com. Retrieved November 23, 2018.

- "Big Rental Films Of 1972". Variety. January 3, 1973. p. 36.

- All The President's Men (1976) 2004 Special Edition, audio commentary by Robert Redford

- Macfarlane, Steve (July 19, 2016). "'The Moment of Unreality': Jeremy Larner on The Candidate (And Much Else)". Brooklyn Magazine. Retrieved May 18, 2021.

- Biskind, Peter (1999). Easy Riders, Raging Bulls: How the Sex 'n' Drugs 'n' Rock 'n' Roll Generation Saved Hollywood. Bloomsbury Publishing. p. 50. ISBN 9780747544210.

- Mathews, Joe (February 23, 2017). "To get things done in California, listen like Nelson Rising". SFGate.com. Retrieved May 18, 2021.

- Kelley, Beverly Merrill (2012). Reelpolitik Ideologies in American Political Film. Lexington Books. Page 23

- Kelley 2012, p. 34.

- Kelley 2012, p. 25.

- Kelley 2012, p. 28.

- Pamela Lillian Valemont, Drowning and Other Undetermined Factors The Death of Natalie Wood, 2013, Lulu.com.

- Canby, Vincent (June 30, 1972). "Screen: 'Candidate,' a Comedy About the State of Politics, Opens". The New York Times: 25. Retrieved November 23, 2018.

- "The Candidate". Variety: 18. June 21, 1972.

- Siskel, Gene (August 9, 1972). "The Candidate". Chicago Tribune. Section 2, p. 5.

- Champlin, Charles (July 2, 1972). "'Candidate' Profiles Politics in Coaxial America". Los Angeles Times. Calendar, p. 1, 55.

- Ebert, Roger (June 18, 1975). "Interview with Bruce Dern". Chicago Sun-Times. Retrieved January 1, 2019.

- Arnold, Gary (July 22, 1972). "A Slick 'Candidate' for (Box) Office". The Washington Post. p. D1.

- Gilliatt, Penelope (July 1, 1972). "The Current Cinema". The New Yorker. pp. 64–65.

- Chappetta, Robert (Winter 1972–73). "The Candidate". Film Quarterly. 26 (2): 54. doi:10.2307/1211329. JSTOR 1211329.

- Combs, Richard (November 1972). "The Candidate". The Monthly Film Bulletin. 39 (466): 229.

- Filmcritic.com review Archived 2006-10-23 at the Wayback Machine

- "The Candidate". Rotten Tomatoes. Retrieved July 15, 2023.

- "The 45th Academy Awards (1973) Nominees and Winners". oscars.org. Retrieved 2011-08-28.

Bibliography

- Callan, Michael Feeney (2011). Robert Redford: The Biography. Knopf.

- Kelley, Beverly Merrill (2012). Reelpolitik Ideologies in American Political Film. Lexington Books.