Cayman Islands

The Cayman (/ˈkeɪmən/) Islands is a self-governing British Overseas Territory, and the largest by population. The 264-square-kilometre (102-square-mile) territory comprises the three islands of Grand Cayman, Cayman Brac and Little Cayman, which are located south of Cuba and north-east of Honduras, between Jamaica and Mexico's Yucatán Peninsula. The capital city is George Town on Grand Cayman, which is the most populous of the three islands.

Cayman Islands | |

|---|---|

| Motto: "He hath founded it upon the seas" | |

| Anthem: "God Save the King" | |

| National song: "Beloved Isle Cayman" | |

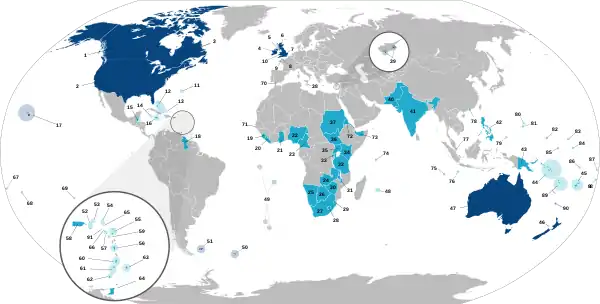

Location of Cayman Islands (circled in red) | |

| |

| Sovereign state | |

| British control | 1670 |

| Self-government | 4 July 1959 |

| Separation from Jamaica | 6 August 1962 |

| Current constitution | 6 November 2009 |

| Capital and largest city | George Town 19.320°N 81.229°W |

| Official languages | English |

| Vernacular languages | Cayman Islands English[1] |

| Ethnic groups (2022[2]) | 36.5% Multiracial 30.2% Black 22.4% White 8.1% Asian 2.8% other[3] |

| Religion |

|

| Demonym(s) | Caymanian |

| Government | Parliamentary dependency under a constitutional monarchy |

• Monarch | Charles III |

• Governor | Jane Owen |

• Premier | Wayne Panton |

| Legislature | Parliament |

| Government of the United Kingdom | |

• Minister | David Rutley |

| Area | |

• Total | 259 km2 (100 sq mi) |

• Water (%) | 1.6 |

| Highest elevation | 43 m (141 ft) |

| Population | |

• 2022 estimate | 81,546[5] (206th) |

• Density | 275.8/km2 (714.3/sq mi) (59th) |

| GDP (PPP) | 2019[6] estimate |

• Total | $4.78 billion |

• Per capita | $73,600 |

| GDP (nominal) | 2020 estimate |

• Total | $5.61 billion[7] (160th) |

• Per capita | $91,392 (7th) |

| HDI (2013) | 0.984 very high |

| Currency | Cayman Islands dollar (KYD) |

| Time zone | UTC-5:00 (EST) |

| Date format | dd/mm/yyyy |

| Driving side | left |

| Calling code | +1-345 |

| UK postcode | KYx-xxxx |

| ISO 3166 code | KY |

| Internet TLD | .ky |

| Website | https://www.gov.ky/ |

The Cayman Islands is considered to be part of the geographic Western Caribbean zone as well as the Greater Antilles. The territory is a major offshore financial centre for international businesses and wealthy individuals, largely as a result of the state not charging taxes on any income earned or stored.[8]

With a GDP per capita of $91,392, the Cayman Islands has the highest standard of living in the Caribbean, and one of the highest in the world.[9] Immigrants from over 130 countries and territories reside in the Cayman Islands.[10]

History

It is likely that the Cayman Islands were first visited by the Amerindians, the Indigenous peoples of the Caribbean.[11] The Cayman Islands got their name from the word for crocodile (caiman) in the language of the Arawak-Taíno people.[12] It is believed that the first European to sight the islands was Christopher Columbus, on 10 May 1503, during his final voyage to the Americas.[13][14] He named them "Las Tortugas", after the large number of turtles found there (which were soon hunted to near-extinction).[13][15]

However, in succeeding decades, the islands began to be referred to as "Caimanas" or "Caymanes", after the caimans present there.[14][13] No immediate colonisation followed Columbus's sighting, but a variety of settlers from various backgrounds eventually arrived, including pirates, shipwrecked sailors, and deserters from Oliver Cromwell's army in Jamaica.[16] Sir Francis Drake briefly visited the islands in 1586.[17]

The first recorded permanent inhabitant, Isaac Bodden, was born on Grand Cayman around 1661. He was the grandson of an original settler named Bodden, probably one of Oliver Cromwell's soldiers involved in the capture of Jamaica from Spain in 1655.[18]

England took formal control of the Cayman Islands, along with Jamaica, as a result of the Treaty of Madrid of 1670.[14] That same year saw an attack on a turtle fishing settlement on Little Cayman by the Spanish under Manuel Ribeiro Pardal.[17] Following several unsuccessful attempts at settlement in what had by then become a haven for pirates,[15] a permanent English-speaking population in the islands dates from the 1730s.[15] With settlement, after the first royal land grant by the Governor of Jamaica in 1734, came the introduction of slaves.[19] Many were purchased and brought to the islands from Africa. That has resulted in the majority of native Caymanians being of African or English descent.[14] The first census taken in the islands, in 1802, showed the population on Grand Cayman to be 933, with 545 of those inhabitants being slaves.[15] Slavery was abolished in the Cayman Islands in 1833, following the passing of the Slavery Abolition Act by the British Parliament. At the time of abolition, there were over 950 slaves of African ancestry, owned by 116 families.[20][13]

On 22 June 1863, the Cayman Islands was officially declared and administered as a dependency of the Crown Colony of Jamaica.[21] The islands continued to be governed as part of the Colony of Jamaica until 1962, when they became a separate Crown colony, after Jamaica became an independent Commonwealth realm.[22][14]

On 8 February 1794, the Caymanians rescued the crews of a group of ten merchant ships, including HMS Convert, an incident that has since become known as the Wreck of the Ten Sail.[13][15] The ships had struck a reef and run aground during rough seas.[23] Legend has it that King George III rewarded the islanders for their generosity with a promise never to introduce taxes, because one of the ships carried a member of the King's family. Despite the legend, the story is not true.[24][15]

In the 1950s, tourism began to flourish, following the opening of Owen Roberts International Airport (ORIA),[25] along with a bank and several hotels, as well as the introduction of a number of scheduled flights and cruise stop-overs.[17][15] Politically, the Cayman Islands were an internally self-governing territory of Jamaica from 1958 to 1962, but they reverted to direct British rule following the independence of Jamaica in 1962.[14] In 1972, a large degree of internal autonomy was granted by a new constitution, with further revisions being made in 1994.[14] The Cayman Islands government focused on boosting the territory's economy via tourism and the attraction of off-shore finance, both of which mushroomed from the 1970s onwards.[15][14] Historically, the Cayman Islands has been a tax-exempt destination, and the government has always relied on indirect and not direct taxes. The territory has never levied income tax, capital gains tax, or any wealth tax, making it a popular tax haven.[26]

In April 1986, the first marine protected areas were designated in the Cayman Islands, making them the first islands in the Caribbean to protect their fragile marine life.

The constitution was further modified in 2001 and 2009, codifying various aspects of human rights legislation.[14]

On 11 September 2004, the island of Grand Cayman, which lies largely unprotected at sea level, was battered by Hurricane Ivan, the worst hurricane to hit the islands in 86 years.[27] It created an 8-foot (2.4 m) storm surge which flooded many areas of Grand Cayman.[14] An estimated 83% of the dwellings on the island were damaged, with 4% requiring complete reconstruction. A reported 70% of all dwellings suffered severe damage from flooding or wind. Another 26% sustained minor damage from partial roof removal, low levels of flooding, or impact with floating or wind-driven hurricane debris.[28] Power, water and communications were disrupted for months in some areas. Within two years, a major rebuilding program on Grand Cayman meant that its infrastructure was almost back to its pre-hurricane condition. Due to the tropical location of the islands, more hurricanes or tropical systems have affected the Cayman Islands than any other region in the Atlantic basin. On average, it has been brushed, or directly hit, every 2.23 years.[29]

Geography

The islands are in the western Caribbean Sea and are the peaks of an undersea mountain range called the Cayman Ridge (or Cayman Rise). This ridge flanks the Cayman Trough, 6,000 m (20,000 ft) deep[30] which lies 6 km (3.7 mi) to the south.[31] The islands lie in the northwest of the Caribbean Sea, east of Quintana Roo, Mexico and Yucatán State, Mexico, northeast of Costa Rica, north of Panama, south of Cuba and west of Jamaica. They are situated about 700 km (430 mi) south of Miami,[32] 750 km (470 mi) east of Mexico,[33] 366 km (227 mi) south of Cuba,[34] and about 500 km (310 mi) northwest of Jamaica.[35] Grand Cayman is by far the largest, with an area of 197 km2 (76 sq mi).[36] Grand Cayman's two "sister islands", Cayman Brac and Little Cayman, are about 120 km (75 mi) east north-east of Grand Cayman and have areas of 38 and 28.5 km2 (14.7 and 11.0 sq mi)[37] respectively. The nearest land mass from Grand Cayman is the Canarreos Archipelago (about 240 km or 150 miles away), whereas the nearest from the easternmost island Cayman Brac is the Jardines de la Reina archipelago (about 160 km or 100 miles away) – both of which are part of Cuba.

All three islands were formed by large coral heads covering submerged ice-age peaks of western extensions of the Cuban Sierra Maestra range and are mostly flat. One notable exception to this is The Bluff on Cayman Brac's eastern part, which rises to 43 m (141 ft) above sea level, the highest point on the islands.[38]

The terrain is mostly a low-lying limestone base surrounded by coral reefs. The portions of prehistoric coral reef that line the coastline and protrude from the water are referred to as ironshore.

Fauna

_male.JPG.webp)

The mammalian species in the Cayman Islands include the introduced Central American agouti[39] and eight species of bats. At least three now extinct native rodent species were present until the discovery of the islands by Europeans. Marine life around the island of the Grand Cayman includes tarpon, silversides (Atheriniformes), French angelfish (Pomacanthus paru), and giant barrel sponges. A number of cetaceans are found in offshore waters. These species include the goose-beaked whale (Ziphius cavirostris), Blainville's beaked whale (Mesoplodon densirostris) and sperm whale (Physeter macrocephalus).

Cayman avian fauna includes two endemic subspecies of Amazona parrots: Amazona leucocephala hesterna or Cuban amazon, presently restricted to the island of Cayman Brac, but formerly also on Little Cayman, and Amazona leucocephala caymanensis or Grand Cayman parrot, which is native to the Cayman Islands, forested areas of Cuba, and the Isla de la Juventud. Little Cayman and Cayman Brac are also home to red-footed and brown boobies.[40][41] Although the barn owl (Tyto alba) occurs in all three of the islands they are not commonplace. The Cayman Islands also possess five endemic subspecies of butterflies.[42] These butterfly breeds can be viewed at the Queen Elizabeth II Botanic Park on the Grand Cayman.

Among other notable fauna at the Queen Elizabeth II Botanic Park is the critically threatened blue iguana which is also known as the Grand Cayman iguana (Cyclura lewisi). The blue iguana is endemic to the Grand Cayman[43] particularly because of rocky, sunlit, open areas near the island's shores that are advantageous for the laying of eggs. Nevertheless, habitat destruction and invasive mammalian predators remain the primary reasons that blue iguana hatchlings do not survive naturally.[44]

The Cuban crocodile (Crocodylus rhombifer) once inhabited the islands.[45] The name "Cayman" is derived from a Carib word for various crocodilians.[46]

Climate

The Cayman Islands has a tropical wet and dry climate, with a wet season from May to October, and a dry season that runs from November to April. Seasonally, there is little temperature change.[47]

A major natural hazard is the tropical cyclones that form during the Atlantic hurricane season from June to November.

On 11 and 12 September 2004, Hurricane Ivan struck the Cayman Islands. The storm resulted in two deaths and caused significant damage to the infrastructure on the islands. The total economic impact of the storms was estimated to be $3.4 billion.[48]

Demographics

Demographics & immigration

While there are a large number of generational Caymanians, many Caymanians today have roots in almost every part of the world. Similarly to countries like the United States, the Cayman Islands is a melting pot with citizens of every background. 52.5% of the population is Non-Caymanian, while 47.5% is Caymanian.

According to the Economics and Statistics Office of the Government of the Cayman Islands, the Cayman Islands had a population of 71,432 at the Census of 10 October 2021, but was estimated by them to have risen to 81,546 as of December 2022, making it the most populous British Overseas Territory.[50] It was revealed in the 2021 census that 56% of the workforce is Non-Caymanian; this is the first time in the territory's history that the number of working immigrants has overtaken the number of working Caymanians.[51] Most Caymanians are of mixed African and European ancestry. Slavery was not common throughout the islands, and once it was abolished, black and white communities seemed to integrate more compliantly than other Caribbean nations and territories, resulting in a more mixed-race population.[52]

The country's demographics are changing rapidly. Immigration plays a huge role, however, the changing demographics in age have sounded alarm bells in the most recent census. In comparison to the 2010 census, the 2021 census has shown that 36% of Cayman's population growth has been in seniors over the age of 65, while only 8% growth was recorded in groups under 15 years of age. This is due to extremely low birth rates among Caymanians, which almost forces the government to have to seek out workers from overseas to sustain the country's economic success. This has raised concerns, however, among many young Caymanians, who worry about the workforce becoming increasingly competitive with the influx of workers, as well as rent and property prices going up.[53]

Because the population has skyrocketed over the last decade, the Premier of the Cayman Islands, Wayne Panton, has stressed that the islands need more careful and managed growth. Many have worried that the country's infrastructure and services cannot cope with the surging population. It is believed that given current trends, the population will reach 100,000 before 2030.[54]

District populations

According to the Economics and Statistics Office, the final result of the 20 October 2021 Census was 71,432; however, according to a late 2022 population report by the same body, the estimated population at the end of 2022 was 81,546,[55] broken down as follows:

| Name of District | Area in sq.km | Population Census 2010 | Population Census 2021 | Population Estimate late 2022[56] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| West Bay | 17.4 | 11,222 | 15,335 | 16,943 |

| George Town | 38.5 | 28,089 | 34,921 | 40,957 |

| Bodden Town | 50.5 | 10,543 | 14,845 | 16,957 |

| North Side | 39.4 | 1,479 | 1,902 | 2,110 |

| East End | 51.1 | 1,407 | 1,846 | 2,274 |

| Total Grand Cayman | 197.0 | 53,160 | 69,175 | 79,242 |

| Little Cayman | 26.0 | 197 | 182 | |

| Cayman Brac | 36.0 | 2,099 | 2,075 | 2,304 |

| Total Cayman Islands | 259.0 | 55,456 | 71,432 | 81,546 |

Religion

The predominant religion on the Cayman Islands is Christianity[57] (66.9%, down from over 80% in 2010).[58] Religions practised include United Church, Church of God, Anglican Church, Baptist Church, Catholic Church, Seventh-day Adventist Church, and Pentecostal Church. Roman Catholic churches are St. Ignatius Church, George Town, Christ the Redeemer Church, West Bay and Stella Maris Church, Cayman Brac. Many citizens are deeply religious, regularly going to church, however, atheism has been on the rise throughout the islands since 2000, with 16.7% now identifying with no religion, according to the 2021 census. Ports are closed on Sundays and Christian holidays. There is also an active synagogue and Jewish community[59] on the island as well as places of worship in George Town for Jehovah's Witnesses and followers of the Bahá'í faith.

In 2020, there were an estimated 121 Muslims in the Cayman Islands.[60]

.jpg.webp)

Languages

The official language of the Cayman Islands is English (90%).[57] Islanders' accents retain elements passed down from English, Scottish, and Welsh settlers (among others) in a language variety known as Cayman Creole. Caymanians of Jamaican origin speak in their own vernacular (see Jamaican Creole and Jamaican English). It is also quite commonplace to hear some residents converse in Spanish[57] as many citizens have relocated from Latin America to work and live on Grand Cayman. The Latin American nations with the greatest representation are Honduras, Cuba, Colombia, Nicaragua, and the Dominican Republic. Spanish speakers comprise approximately between 10 and 12% of the population and are predominantly of the Caribbean dialect. Tagalog is spoken by about 8% of inhabitants most of whom are Filipino residents on work permits.[57]

Economy

According to Forbes, the Cayman Islands has the 7th strongest currency in the world (the CI dollar or KYD), with US $1.00 equivalent to CI $0.80.[61]

The economy of the Cayman Islands is dominated by financial services and tourism, together accounting for 50–60% of Gross Domestic Product.[62] The nation's low tax rates have led to it being used as a tax haven for corporations; there are 100,000 companies registered in the Cayman Islands, more than the population itself. The Cayman Islands have come under criticism for allegations of money laundering and other financial crimes, including a 2016 statement by then US president Barack Obama that described a particular building which was the registered address of over 12,000 corporations as a "tax scam".[63]

The Cayman Islands holds a relatively low unemployment rate of about 4.24% as of 2015,[64] lower than the value of 4.7% that was recorded in 2014.

With an average income of US$71,549, Caymanians have the highest standard of living in the Caribbean. According to the CIA World Factbook, the Cayman Islands' real GDP per capita is the tenth highest in the world, but the CIA's data for Cayman dates to 2018 and is likely to be lower than present-day values.[65] The territory prints its own currency, the Cayman Islands dollar (KYD), which is pegged to the US dollar US$1.227 to 1 KYD. However, in many retail stores throughout the islands, the KYD is typically traded at US$1.25.[66]

Cayman Islands have a high cost of living, even when compared to UK and US.[67] For example, a loaf of multigrain bread is $5.49 (KYD), while a similar loaf sells for $2.47 (KYD) in the US and $1.36 (KYD) in the UK.[68]

The minimum wage (as of February 2021) is $6 KYD for standard positions, and $4.50 for workers in the service industry, where tips supplement income.[69] This contributes to wealth disparity.[70] A small segment of the population lives in condemned properties lacking power and running water.[71]

The government has established a Needs Assessment Unit to relieve poverty in the islands.[72] Local charities, including Cayman's Acts of Random Kindness (ARK) also provide assistance.

The government's primary source of income is indirect taxation: there is no income tax, capital gains tax, or corporation tax.[26] An import duty of 5% to 22% (automobiles 29.5% to 100%) is levied against goods imported into the islands. Few goods are exempt; notable exemptions include books, cameras, and perfume.[73]

Tourism

One of Grand Cayman's main attractions is Seven Mile Beach, site of a number of the island's hotels and resorts. Named one of the Ultimate Beaches by Caribbean Travel and Life, Seven Mile Beach (due to erosion over the years, the number has decreased to 5.5 miles) is a public beach on the western shore of Grand Cayman Island.[74] Historical sites in Grand Cayman, such as Pedro St. James Castle in Savannah, also attract visitors.[75]

All three islands offer scuba diving, and the Cayman Islands are home to several snorkelling locations where tourists can swim with stingrays. The most popular area to do this is Stingray City, Grand Cayman. Stingray City is a top attraction in Grand Cayman and originally started in the 1980s when divers started feeding squid to stingrays. The stingrays started to associate the sound of the boat motors with food, and thus visit this area year-round.[76]

There are two shipwrecks off the shores of Cayman Brac, including the MV Captain Keith Tibbetts;[77] Grand Cayman also has several shipwrecks off its shores, including one deliberate one. On 30 September 1994, the USS Kittiwake was decommissioned and struck from the Naval Vessel Register. In November 2008 her ownership was transferred for an undisclosed amount to the government of the Cayman Islands, which had decided to sink the Kittiwake in June 2009 to form a new artificial reef off Seven Mile Beach, Grand Cayman. Following several delays, the ship was finally scuttled according to plan on 5 January 2011. The Kittiwake has become a dynamic environment for marine life. While visitors are not allowed to take anything, there are endless sights. Each of the five decks of the ship offers squirrelfish, rare sponges, Goliath groupers, urchins, and more. Experienced and beginner divers are invited to swim around the Kittiwake.[78] Pirates Week is an annual 11-day November festival started in 1977 by the then-Minister of Tourism Jim Bodden to boost tourism during the country's tourism slow season.[79]

Other Grand Cayman tourist attractions include the ironshore landscape of Hell; the 23-acre (93,000 m2) marine theme park "Cayman Turtle Centre: Island Wildlife Encounter", previously known as "Boatswain's Beach"; the production of gourmet sea salt; and the Mastic Trail, a hiking trail through the forests in the centre of the island. The National Trust for the Cayman Islands provides guided tours weekly on the Mastic Trail and other locations.[80]

Another attraction to visit on Grand Cayman is the Observation Tower, located in Camana Bay. The Observation Tower is 75 feet tall and provides 360-degree views across Seven Mile Beach, George Town, the North Sound, and beyond. It is free to the public and climbing the tower has become a popular thing to do in the Cayman Islands.[81]

Points of interest include the East End Light (sometimes called Gorling Bluff Light), a lighthouse at the east end of Grand Cayman island. The lighthouse is the centrepiece of East End Lighthouse Park, managed by the National Trust for the Cayman Islands; the first navigational aid on the site was the first lighthouse in the Cayman Islands.

Shipping

As of 31 December 2015, 360 commercial vessels and 1,674 pleasure craft were registered in the Cayman Islands totalling 4.3 million GT.[82]

Labour

The Cayman Islands has a population of 69,656 (as of 2021) and therefore a limited workforce.[83] Work permits may, therefore, be granted to foreigners. On average, there have been more than 24,000+ foreigners holding valid work permits.[84]

Work permits for non-citizens

To work in the Cayman Islands as a non-citizen, a work permit is required. This involves passing a police background check and a health check. A prospective immigrant worker will not be granted a permit unless certain medical conditions are met, including testing negative for syphilis and HIV. A permit may be granted to individuals on special work.

A foreigner must first have a job to move to the Cayman Islands. The employer applies and pays for the work permit.[85] Work permits are not granted to foreigners who are in the Cayman Islands (unless it is a renewal). The Cayman Islands Immigration Department requires foreigners to remain out of the country until their work permit has been approved.[86]

The Cayman Islands presently imposes a controversial "rollover" in relation to expatriate workers who require a work permit. Non-Caymanians are only permitted to reside and work within the territory for a maximum of nine years unless they satisfy the criteria of key employees. Non-Caymanians who are "rolled over" may return to work for additional nine-year periods, subject to a one-year gap between their periods of work. The policy has been the subject of some controversy within the press. Law firms have been particularly upset by the recruitment difficulties that it has caused.[87] Other less well-remunerated employment sectors have been affected as well. Concerns about safety have been expressed by diving instructors, and realtors have also expressed concerns. Others support the rollover as necessary to protect Caymanian identity in the face of immigration of large numbers of expatriate workers.[88]

Concerns have been expressed that in the long term, the policy may damage the preeminence of the Cayman Islands as an offshore financial centre by making it difficult to recruit and retain experienced staff from onshore financial centres. Government employees are no longer exempt from this "rollover" policy, according to this report in a local newspaper.[89] The governor has used his constitutional powers, which give him absolute control over the disposition of civil service employees, to determine which expatriate civil servants are dismissed after seven years service and which are not.[89]

This policy is incorporated in the Immigration Law (2003 revision), written by the United Democratic Party government, and subsequently enforced by the People's Progressive Movement Party government. Both governments agree to the term limits on foreign workers, and the majority of Caymanians also agree it is necessary to protect local culture and heritage from being eroded by a large number of foreigners gaining residency and citizenship.[90]

CARICOM Single Market Economy

In recognition of the CARICOM (Free Movement) Skilled Persons Act which came into effect in July 1997 in some of the CARICOM countries such as Jamaica and which has been adopted in other CARICOM countries, such as Trinidad and Tobago[91] it is possible that CARICOM nationals who hold the "A Certificate of Recognition of Caribbean Community Skilled Person" will be allowed to work in the Cayman Islands[92] under normal working conditions.

Government

The Cayman Islands are a British overseas territory, listed by the UN Special Committee of 24 as one of the 16 non-self-governing territories. The current Constitution, incorporating a Bill of Rights, was ordained by a statutory instrument of the United Kingdom in 2009.[93] A 19-seat (not including two non-voting members appointed by the Governor which brings the total to 21 members) Parliament is elected by the people every four years to handle domestic affairs.[94] Of the elected Members of the Parliament (MPs), seven are chosen to serve as government Ministers in a Cabinet headed by the Governor. The Premier is appointed by the Governor.[95]

A Governor is appointed by the King of the United Kingdom on the advice of the British Government to represent the monarch.[96] Governors can exercise complete legislative and executive authority if they wish through blanket powers reserved to them in the constitution.[97] Bills which have passed the Parliament require royal assent before becoming effective. The Constitution empowers the Governor to withhold royal assent in cases where the legislation appears to him or her to be repugnant to or inconsistent with the Constitution or affects the rights and privileges of the Parliament or the Royal Prerogative, or matters reserved to the Governor by article 55.[98] The executive authority of the Cayman Islands is vested in the King and is exercised by the Government, consisting of the Governor and the Cabinet.[99] There is an office of the Deputy Governor, who must be a Caymanian and have served in a senior public office. The Deputy Governor is the acting Governor when the office of Governor is vacant, or the Governor is not able to discharge his or her duties or is absent from the Cayman Islands.[100] The current Governor of the Cayman Islands is Jane Owen.[101]

The Cabinet is composed of two official members and seven elected members, called Ministers; one of whom is designated Premier. The Premier can serve for two consecutive terms after which he or she is barred from attaining the office again. Although an MP can only be Premier twice any person who meets the qualifications and requirements for a seat in the Parliament can be elected to the Parliament indefinitely.[102]

There are two official members of the Parliament, the Deputy Governor and the Attorney General. They are appointed by the Governor in accordance with His Majesty's instructions, and although they have seats in the Parliament, under the 2009 Constitution, they do not vote. They serve in a professional and advisory role to the MPs, the Deputy Governor represents the Governor who is a representative of the King and the British Government. While the Attorney General serves to advise on legal matters and has special responsibilities in Parliament, they are generally responsible for changes to the Penal code.

The seven Ministers are voted into office by the 19 elected members of the Parliament of the Cayman Islands. One of the Ministers, the leader of the majority political party, is appointed Premier by the Governor.

After consulting the Premier, the Governor allocates a portfolio of responsibilities to each Cabinet Minister. Under the principle of collective responsibility, all Ministers are obliged to support in the Parliament any measures approved by Cabinet.

Almost 80 departments, sections and units carry out the business of government, joined by a number of statutory boards and authorities set up for specific purposes, such as the Port Authority, the Civil Aviation Authority, the Immigration Board, the Water Authority, the University College Board of Governors, the National Pensions Board and the Health Insurance Commission.

Since 2000, there have been two official major political parties: The Cayman Democratic Party (CDP) and the People's Progressive Movement (PPM). While there has been a shift to political parties, many contending for office still run as independents. The two parties are notably similar, though they consider each other rivals in most cases, their differences are generally in personality and implementation rather than actual policy. The Cayman Islands generally lacks any form of organised political parties.[103] As of the May 2017 General Election, members of the PPM and CDP have joined with three independent members to form a government coalition despite many years of enmity.[104]

Police

Policing in the country is provided chiefly by the RCIPS or Royal Cayman Islands Police Service and the CICBC or Cayman Islands Customs & Border Control. These two agencies co-operate in aspects of law enforcement, including their joint marine unit.[105][106]

Military and defence

The defence of the Cayman Islands is the responsibility of the United Kingdom. The Royal Navy maintains a ship on permanent station in the Caribbean (HMS Medway (P223)) and additionally sends another Royal Navy or Royal Fleet Auxiliary ship as a part of Atlantic Patrol (NORTH) tasking. These ships' main mission in the region is to maintain British sovereignty for the overseas territories, provide humanitarian aid and disaster relief during disasters such as hurricanes, which are common in the area, and to conduct counter-narcotic operations.

Cayman Islands Regiment

On 12 October 2019, the government announced the formation of the Cayman Islands Regiment, a new British Armed Forces unit. The Cayman Islands Regiment which became fully operational in 2020, with an initial 35–50 personnel of mostly reservists. Between 2020 through 2021 the Regiment grew to over a hundred personnel and over the next several years expected to grow to over a several hundred personnel.[107][108][109]

In mid-December 2019, recruitment for commanding officers and junior officers began, with the commanding officers expected to begin work in January 2020 and the junior officers expected to begin in February 2020.[110]

In January 2020, the first officers were chosen for the Cayman Islands Regiment.[111]

Since the formation of the Regiment, it has been deployed on a few operational tours providing HADR or Humanitarian Aid and Disaster Relief as well as assisting with the COVID19 Pandemic.

Cadet Corps

The Cayman Islands Cadet Corps was formed in March 2001 and carries out military-type training with teenage citizens of the country.[112]

Coast Guard

In 2018, the PPM-led Coalition government pledged to form a coast guard to protect the interests of the Cayman Islands, especially in terms of illegal immigration and illegal drug importation as well as search and rescue.[113] In mid-2018, the Commander and second-in-Command of the Cayman Islands Coast Guard were appointed. Commander Robert Scotland was appointed as the first commanding officer and Lieutenant Commander Leo Anglin was appointed as Second-in-Command.[114]

In mid-2019, the commander and second-in-command took part in international joint operations with the United States Coast Guard and the Jamaica Defense Force Coast Guard called Operation Riptide. This makes it the first deployment for the Cayman Islands Coast Guard and the first in ten years any Cayman Representative has been on a foreign military ship for a counternarcotic operation.[115][116]

In late November 2019, it was announced that the Cayman Islands Coast Guard would become operational in January 2020, with initial total of 21 Coast Guardsmen half of which would come from the joint marine unit, with further recruitment in the new year. One of the many taskings of the Coast Guard will be to push enforcement of all laws that apply to the designated Wildlife Interaction Zone.[117]

On 5 October 2021, the Cayman Islands Parliament passed the Cayman Islands Coast Guard Act thus establishing the Cayman Islands Coast Guard as a uniformed and disciplined department of Government.[118]

Taxation

No direct taxation is imposed on residents and Cayman Islands companies. The government receives the majority of its income from indirect taxation. Duty is levied against most imported goods, which is typically in the range of 22% to 25%. Some items are exempted, such as baby formula, books, cameras, electric vehicles and certain items are taxed at 5%. Duty on automobiles depends on their value. The duty can amount to 29.5% up to $20,000.00 KYD CIF (cost, insurance and freight) and up to 42% over $30,000.00 KYD CIF for expensive models. The government charges flat licensing fees on financial institutions that operate in the islands and there are work permit fees on foreign labour. A 13% government tax is placed on all tourist accommodations in addition to a US$37.50 airport departure tax which is built into the cost of an airline ticket. There is a 7.5% sales tax on the proceeds of the sale of the property, payable by the purchaser. There are no taxes on corporate profits, capital gains, or personal income. There are no estate or death inheritance taxes payable on Cayman Islands real estate or other assets held in the Cayman Islands.

The legend behind the lack of taxation comes from the Wreck of the Ten Sail, when multiple ships ran aground on the reef off the north coast of Grand Cayman. Local fishermen are said to have then sailed out to rescue the crew and salvage goods from the wrecks. It is said that out of gratitude, and due to their small size, King George III then issued the edict that the citizens of the country of the Cayman Islands would never pay tax.[119] There is, however, no documented evidence for this story besides oral tradition.

Foreign relations

Foreign policy is controlled by the United Kingdom, as the islands remain an overseas territory of the United Kingdom. Although in its early days, the Cayman Islands' most important relationships were with Britain and Jamaica, in recent years, as a result of economic dependence, a relationship with the United States has developed.

Though the Cayman Islands is involved in no major international disputes, they have come under some criticism due to the use of their territory for narcotics trafficking and money laundering. In an attempt to address this, the government entered into the Narcotics Agreement of 1984 and the Mutual Legal Assistance Treaty of 1986 with the United States, to reduce the use of their facilities associated with these activities. In more recent years, they have stepped up the fight against money laundering, by limiting banking secrecy, introducing requirements for customer identification and record keeping, and requiring banks to co-operate with foreign investigators.

Due to their status as an overseas territory of the UK, the Cayman Islands has no separate representation either in the United Nations or in most other international organisations. However, the Cayman Islands still participates in some international organisations, being an associate member of Caricom and UNESCO, and a member of a sub-bureau of Interpol.[120]

Emergency services

Access to emergency services is available using 9-1-1, the emergency telephone number, the same number as is used in Canada and the United States.[121] The Cayman Islands Department of Public Safety's Communications Centre processes 9-1-1 and non-emergency police assistance, ambulance service, fire service and search and rescue calls for all three islands. The Communications Centre dispatches RCIP and EMS units directly; the Cayman Islands Fire Service maintains their own dispatch room at the airport fire station.[122]

The police services are handled by the Royal Cayman Islands Police Service. The fire services are handled by the Cayman Islands Fire Service. There are 4 main hospitals in the Cayman Islands, private and public health in the Cayman Islands with various localised health clinics around the islands.

Infrastructure

Ports

George Town is the port capital of Grand Cayman. There are no berthing facilities for cruise ships, but up to four cruise ships can anchor in designated anchorages. There are three cruise terminals in George Town, the North, South, and Royal Watler Terminals. The ride from the ship to the terminal is about 5 minutes.[123]

Airports and airlines

There are three airports which serve the Cayman Islands. The islands' national flag carrier is Cayman Airways, with Owen Roberts International Airport hosting the airline as its hub.

• Owen Roberts International Airport • Charles Kirkconnell International Airport • Edward Bodden Airfield

Main highways

There are three highways, as well as crucial feeder roads that serve the Cayman Islands capital city, George Town. Residents in the east of the city will rely on the East-West Arterial Bypass to go into George Town; as well as Shamrock Road coming from Bodden Town and the eastern districts. Other main highways and carriageways include:

• Linford Pierson Highway (most popular roadway into George Town from the east) • Esterly Tibbetts Highway (serves commuters to the north of the city and West Bay) • North Sound Road (main road for Central George Town) • South Sound Road (used by commuters to the south of the city) • Crewe Road (alternative to taking Linford Pierson Highway)

Education

Primary and secondary schools

The Cayman Islands Education Department operates state schools. Caymanian children are entitled to free primary and secondary education. There are two public high schools on Grand Cayman, John Gray High School and Clifton Hunter High School, and one on Cayman Brac, Layman E. Scott High School. Various churches and private foundations operate several private schools.

Colleges and universities

The University College of the Cayman Islands has campuses on Grand Cayman and Cayman Brac and is the only government-run university on the Cayman Islands.[124]

The International College of the Cayman Islands is a private college in Grand Cayman. The college was established in 1970 and offers associate's, bachelor's and master's degree programmes.[125] Grand Cayman is also home to St. Matthew's University, which includes a medical school and a school of veterinary medicine.[126] The Cayman Islands Law School, a branch of the University of Liverpool, is based on Grand Cayman.[127]

The Cayman Islands Civil Service College, a unit of the Cayman Islands government organised under the Portfolio of the Civil Service, is in Grand Cayman. Co-situated with University College of the Cayman Islands, it offers both degree programs and continuing education units of various sorts. The college opened in 2007 and is also used as a government research centre.

There is a University of the West Indies Open campus in the territory.[128]

Sports

Truman Bodden Sports Complex is a multi-use complex in George Town. The complex is separated into an outdoor, six-lane 25-metre (82 ft) swimming pool, full purpose track and field and basketball/netball courts. The field surrounded by the track is used for association football matches as well as other field sports. The track stadium holds 3,000 people.

Association football is the national and most popular sport, with the Cayman Islands national football team representing the Cayman Islands in FIFA.[129]

The Cayman Islands Basketball Federation joined the international basketball governing body FIBA in 1976.[130] The country's national team attended the Caribbean Basketball Championship for the first time in 2011. Cayman Islands National Male National Team has won back-to-back Gold Medal victories in 2017 and 2019 Natwest Island Games.

Rugby union is a developing sport, and has its own national men's team, women's team, and Sevens team. The Cayman Men's Rugby 7s team is second in the region after the 2011 NACRA 7s Championship.

The Cayman Islands are a member of FIFA, the International Olympic Committee and the Pan American Sports Organisation, and also competes in the biennial Island Games.[131]

The Cayman Islands are a member of the International Cricket Council which they joined in 1997 as an Affiliate, before becoming an Associate member in 2002. The Cayman Islands national cricket team represents the islands in international cricket. The team has previously played the sport at first-class, List A and Twenty20 level. It competes in Division Five of the World Cricket League.[132]

Squash is popular in the Cayman Islands with a vibrant community of mostly ex-pats playing out of the 7-court South Sound Squash Club. In addition, the women's professional squash association hosts one of their major events each year in an all-glass court being set up in Camana Bay. In December 2012, the former Cayman Open will be replaced by the Women's World Championships, the largest tournament in the world. The top Cayman men's player, Cameron Stafford is No. 2 in the Caribbean and ranked top 200 on the men's professional circuit.

Flag football (CIFFA) has men's, women's, and mixed-gender leagues.

Other organised sports leagues include softball, beach volleyball, Gaelic football and ultimate frisbee.

The Cayman Islands Olympic Committee was founded in 1973 and was recognised by the IOC (International Olympic Committee) in 1976.

In April 2005 Black Pearl Skate Park was opened in Grand Cayman by Tony Hawk. At the time the 52,000 square feet (4,800 m2) park was the largest in the Western Hemisphere.[133][134]

In February 2010, the first purpose-built track for kart racing in the Cayman Islands was opened.[135] Corporate karting Leagues at the track have involved widespread participation with 20 local companies and 227 drivers taking part in the 2010 Summer Corporate Karting League.[136]

Cydonie Mothersille was the first track and field athlete from the country to make an Olympic final at the 2008 Olympic Games. She also won a bronze medal in the 200m at the 2001 World Championships in Athletics and gold in the same event at the 2010 Commonwealth Games.[137]

Arts and culture

Music

The Cayman National Cultural Foundation manages the F.J. Harquail Cultural Centre and the US$4 million Harquail Theatre. The Cayman National Cultural Foundation, established in 1984, helps to preserve and promote Cayman folk music, including the organisation of festivals such as the Cayman Islands International Storytelling Festival, the Cayman JazzFest, Seafarers Festival and Cayfest.[138] The jazz, calypso and reggae genres of music styles feature prominently in Cayman music as celebrated cultural influences.[139]

Art

The National Gallery of the Cayman Islands is an art museum in George Town.[140] Founded in 1996, NGCI is an arts organisation that seeks to fulfil its mission through exhibitions, artist residencies, education/outreach programmes and research projects in the Cayman Islands. The NGCI is a non-profit institution, part of the Ministry of Health and Culture.[141]

Media

There are two print newspapers currently in circulation throughout the islands: the Cayman Compass and The Caymanian Times. Online news services include Cayman Compass, Cayman News Service, Cayman Marl Road, The Caymanian Times and Real Cayman News.[142] Olive Hilda Miller was the first paid reporter to work for a Cayman Islands newspaper, beginning her career on the Tradewinds newspaper, which her work helped to establish.[143][144]

Local radio stations are broadcast throughout the islands.

Feature films that have been filmed in the Cayman Islands include: The Firm, Haven, Cayman Went[145] and Zombie Driftwood.[146]

Television in the Cayman Islands consist of three over-the-air broadcast stations, Trinity Broadcasting Network - CIGTV (the government-owned channel) - Seventh Day Adventist Network. Cable television is available in the Cayman Islands through three providers, C3 Pure Fibre - FLOW TV - Logic TV. Satellite television is provided by Dish Direct TV.[147]

Broadband is widely available on the Cayman Islands, with Digicel, C3 Pure Fibre, FLOW and Logic all providing super fast fibre broadband to the islands.[148]

Notable Caymanians

- Truman Bodden, politician

- William Warren Conolly, politician and national hero

- McKeeva Bush, politician

- Thomas Jefferson, Caymanian politician

- Sybil Ione McLaughlin, national hero and First Speaker of the House

- Sir Alden McLaughlin, politician and second Caymanian to receive a knighthood

- Sybil Joyce Hylton, national hero

- Mary Evelyn Wood, national hero

- Edna Moyle, former Speaker of the House

- Kurt Tibbetts, politician

- David Ritch, attorney and Chairman of the Board of Directors of CIBC FirstCaribbean International Bank

- Jeffrey Webb, infamous former CONCACAF president and FIFA vice-president

- Bernard K. Passman, jeweller, founded his business on Grand Cayman in 1975

- Kenneth Dart, businessman and owner of Camana Bay.

- Selita Ebanks, fashion model

- Leila Ross-Shier, musician, educator and composer of "Beloved Isle Cayman"

- The Barefoot Man, folk singer and national icon

- Frank E. Flowers, filmmaker, director and screenwriter

- John Reno Jackson, multidisciplinary artist

- Gladwyn K. Bush, folk artist

- Jason Gilbert, record producer and songwriter

- Ronald Forbes, Olympic athlete

- Brett Fraser, Olympic athlete

- Shaune Fraser, Olympic athlete

- Kemar Hyman, Olympic athlete

- Edison Mclean, first Caymanian gold medalist in Olympic skeet, Island Games[149]

- Raegan Rutty, Olympic gymnast

- Cameron Stafford, 2010 Caribbean Junior Squash Champion

- Kareem Streete-Thompson, Olympic athlete

- Cydonie Mothersille, track and field athlete and Olympian

- Dow Travers, Olympic athlete

References

- "Cayman Islands Languages". FamilySearch. 3 September 2021. Archived from the original on 23 March 2022. Retrieved 23 March 2022.

- "Ethnic Groups - Cayman Islands Headline News" (PDF). Cayman Islands Ethnic Groups. 25 February 2022. Archived (PDF) from the original on 31 July 2022. Retrieved 25 May 2022.

- "Background Note: Cayman Islands". United States Department of State. 18 February 2011. Archived from the original on 31 March 2022. Retrieved 31 July 2011.

- "Cayman Islands" (PDF). October 2021. Archived (PDF) from the original on 31 July 2022. Retrieved 29 July 2022.

- 1 September 2022 "Cayman Islands 2021 Census Final Report". Cayman Islands Government. 18 June 2021. Archived from the original on 1 September 2022.

{{cite web}}: Check|url=value (help) - "Central America :: Cayman Islands — The World Factbook - Central Intelligence Agency". Cia.gov. Archived from the original on 13 January 2021. Retrieved 14 September 2019.

This article incorporates public domain material from The World Factbook. CIA.

This article incorporates public domain material from The World Factbook. CIA. - "Cayman Islands | Data". data.worldbank.org. Archived from the original on 9 August 2021. Retrieved 9 August 2021.

- Rogoff, Natasha Lance (19 February 2004). "Tax me if you can. Haven or Havoc?". Pbs.org. Archived from the original on 22 February 2004. Retrieved 25 August 2017.

- "Cayman Islands - Place Explorer". Data Commons. Archived from the original on 16 August 2022. Retrieved 19 March 2022.

- Boxall, Joanna (18 February 2021). "Facts & Figures of the Cayman Islands". Cayman Resident. Archived from the original on 31 March 2022. Retrieved 19 March 2022.

- "History of the Cayman Islands: 1503 to 1970s". caymanresident.com.

- "World Directory of Minorities and Indigenous Peoples - Cayman Islands". www.refworld.org.

- "History of Cayman Islands". Cayman Islands Government. Archived from the original on 9 September 2018. Retrieved 7 July 2019.

- "Cayman Islands". Encyclopædia Britannica. Archived from the original on 6 May 2021. Retrieved 7 July 2019.

- "History of the Cayman Islands". Explore Cayman. Archived from the original on 7 March 2021. Retrieved 7 July 2019.

- Bauman, Robert (2007). The Complete Guide to Offshore Residency. The Sovereign Society. p. 115. ISBN 978-0-9789210-9-5.

- "Key to Cayman - HISTORY – ISLANDS THAT TIME FORGOT". 22 January 2016. Archived from the original on 1 March 2021. Retrieved 7 July 2019.

- Thompson, Keith (2010). Life in The Caribbean. New Africa Press. p. 152. ISBN 978-9987-16-015-0.

- "Cayman Islands History". Gocayman.ky. Archived from the original on 12 October 2008.

- The Cayman Islands Annual Report 1988, Cayman Islands, 1988, p. 127

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Cawley, Charles. Colonies in Conflict: The History of the British Overseas Territories.

- Newman, Graeme R. (2010). Crime and Punishment Around the World: Africa and the Middle East. Abc-Clio, LLC. p. 82. ISBN 978-0-313-35133-4..

- Wood, Lawson (2007). The Cayman Islands. New Holland Publishers, Limited. p. 12. ISBN 978-1-84537-897-4..

- Zayas y Alfonso, Alfredo (1914). Lexografía Antillana. Havana: El Siglo XX Press.

- "Airport Authority of Cayman Islands - CIAA". Caymanairports.com. Archived from the original on 13 May 2021. Retrieved 13 May 2021.

- Biswas, Rajiv (2002). International Tax Competition: A Developing Country Perspective. Commonwealth Secretariat. p. 38. ISBN 0-85092-688-2..

- Thompson, Keith (2010). Caribbean Islands: The Land and the People. New Africa Press. p. 152. ISBN 978-9987-16-018-1.

- "Hurricane Ivan Remembered". Hazard Management Cayman Islands. Retrieved 26 July 2012.

- "Grand Cayman's history with tropical systems". hurricanecity.com. Archived from the original on 29 April 2011. Retrieved 31 July 2011.

- "Publications". Archived from the original on 23 December 2015. Retrieved 23 December 2015.

- Bush, Phillippe G. Grand Cayman, British West Indies Archived 19 February 2012 at the Wayback Machine. UNESCO Coastal region and small island papers 3.

- "Coordinates + total distance". web page. mapcrow. Archived from the original on 4 January 2012. Retrieved 23 October 2011.

- "Quintana Roo to Cayman Islands". web page. distancesto. Archived from the original on 5 July 2017. Retrieved 18 January 2015.

- "Distance from Cayman Islands to Cuba". web page. distancefromto.net/. 2011. Archived from the original on 4 January 2012. Retrieved 23 October 2011.

- "Coordinates and total distance". web page. Mapcrow. Archived from the original on 4 January 2012. Retrieved 23 October 2011.

- Bush Archived 19 February 2012 at the Wayback Machine. Unesco.org. Retrieved on 12 April 2014.

- Glenn Gerber. "Lesser Caymans iguana Cyclura nubila caymanensis". web page. The World Conservation Union. Archived from the original on 8 October 2011. Retrieved 23 October 2011.

- "World Atlas Highest and Lowest points". web page. Graphic Maps. Archived from the original on 24 August 2011. Retrieved 23 October 2011.

- Woods, C.A.; Kilpatrick, C.W. (2005). "Infraorder Hystricognathi". In Wilson, D.E.; Reeder, D.M (eds.). Mammal Species of the World: A Taxonomic and Geographic Reference (3rd ed.). Johns Hopkins University Press. p. 1558. ISBN 978-0-8018-8221-0. OCLC 62265494.

- Red-footed Boobies of Little Cayman – National Trust for the Cayman Islands Archived 2 October 2015 at the Wayback Machine. Nationaltrust.org.ky. Retrieved on 12 April 2014.

- Cayman Brac | Caribbean Diving, Cayman Islands Vacation | Cayman Islands Archived 1 May 2013 at the Wayback Machine. Caymanislands.ky. Retrieved on 12 April 2014.

- Askew, R. R. and Stafford, P. A. van B. (2008) Butterflies of the Cayman Islands. Apollo Books, Stenstrup. ISBN 978-87-88757-85-9.

- Grand Cayman Blue Iguana takes step back from extinction Archived 11 November 2012 at the Wayback Machine. IUCN (20 October 2012). Retrieved on 12 April 2014.

- Morgan, Gary; Franz, Richard; Ronald Crombie (1993). "The Cuban Crocodile, Crocodylus rhombifer, from Late Quaternary Fossil Deposits on Grand Cayman" (PDF). Caribbean Journal of Science. 29 (3–4): 153–164. Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 October 2022.

- "The Cayman Islands – History". Gov.ky. Archived from the original on 9 September 2018. Retrieved 17 August 2018.

A 1523 map show[s] all three Islands with the name Lagartos, meaning alligators or large lizards, but by 1530 the name Caymanas was being used. It is derived from the Carib Indian word for the marine crocodile, which is now known to have lived in the Islands.

- "When to Go in Cayman Islands | Frommer's". Frommers.com. Archived from the original on 2 October 2016. Retrieved 28 September 2016.

- Boxall, Simon (9 September 2008). "Hurricane Ivan Remembered – Cayman Prepared". Gov.ky. Archived from the original on 27 February 2021. Retrieved 22 April 2012.

- "Demographic Characteristics". Cayman Islands Government. 2021. Archived from the original on 4 October 2022. Retrieved 20 September 2022.

- "Premier: Census shows Cayman needs more careful, managed growth". 28 July 2022. Archived from the original on 1 September 2022. Retrieved 1 September 2022.

- "Census reveals 56% of workers not Caymanian". Caymannewsservice.com. 25 February 2022. Archived from the original on 8 April 2022. Retrieved 19 March 2022.

- Boxall, Joanna (11 January 2023). "The History of Slavery in the Cayman Islands". Cayman Resident. Retrieved 23 May 2023.

- "Ageing society one of Cayman's demographic challenges". 14 March 2022. Archived from the original on 14 March 2022. Retrieved 14 March 2022.

- "Premier: Census shows Cayman needs more careful, managed growth". 28 July 2022. Archived from the original on 28 July 2022. Retrieved 28 July 2022.

- "Cayman Islands Fall 2022 Labour Report" (PDF). September 2022. Archived from the original on 1 September 2022. Retrieved 1 September 2022.

- "Cayman Islands Fall 2022 Labour Report" (PDF). Eso.ky. Archived (PDF) from the original on 3 August 2022. Retrieved 10 April 2022.

- "Central America :: Cayman Islands — The World Factbook - Central Intelligence Agency". Cia.gov. Archived from the original on 13 January 2021. Retrieved 5 August 2020.

- "The Cayman Islands' 2021 Census of Population and Housing Report" (PDF). Economics and Statistics Office, Government of the Cayman Islands. July 2022. Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 October 2022.

- The Jewish Community of the Cayman Islands www.jewish.ky Archived 22 January 2020 at the Wayback Machine

- Kettani, Houssain. "Muslim Population in the Americas". ResearchGate.

- "Strongest Currencies in the World". Forbes. 5 July 2023.

- "The World Factbook – Central Intelligence Agency". Cia.gov. 29 November 2021. Archived from the original on 13 January 2021. Retrieved 24 January 2021.

- "The Cayman Islands – home to 100,000 companies and the £8.50 packet of fish fingers". The Guardian. 18 January 2016. Archived from the original on 18 January 2016. Retrieved 16 February 2020.

- "Unemployment, total (% of total labor force) (national estimate) - Cayman Islands". World Bank. Archived from the original on 22 September 2019. Retrieved 22 September 2019.

- "CIA – The World Factbook – Cayman Islands". Archived from the original on 13 January 2021. Retrieved 10 November 2020.

- "Moving to Grand Cayman". CaymanNewResident.com. Archived from the original on 25 June 2014. Retrieved 21 July 2014.

- Whittaker, James; Klein, Michael (9 February 2021). "Counting the cost of living in the Cayman Islands". Cayman Compass. Archived from the original on 28 October 2021. Retrieved 19 October 2021.

- Whittaker, James; Klein, Michael (9 February 2021). "Cayman shoppers pay premium for groceries". Cayman Compass. Archived from the original on 28 October 2021. Retrieved 19 October 2021.

- "Basic Minimum Wage". Cayman Islands Immigration Department. Archived from the original on 17 October 2021. Retrieved 19 October 2021.

- Whittaker, James (9 February 2021). "Economist cautions Cayman must address wealth disparity". Cayman Compass. Archived from the original on 21 September 2021. Retrieved 2 October 2021.

- Whittaker, James (10 August 2021). "Families still living in condemned properties". Cayman Compass. Archived from the original on 22 September 2021. Retrieved 2 October 2021.

- "The reality of Poverty In Cayman". Cayman Reporter. 5 August 2015. Archived from the original on 23 April 2016. Retrieved 11 April 2016.

- "A Bill for a Law to Increase Various Duties Under the Customs Tariff Law (2002 Revision); to Increase the Rates of Package Tax; And for Incidental and Connected Purposes" (PDF). Cayman Islands Legislative Assembly. 7 December 2009. Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 October 2022. Retrieved 25 June 2018.

- Seven Mile Beach | Grand Cayman, Caribbean Vacation | Cayman Islands Archived 1 May 2013 at the Wayback Machine. Caymanislands.ky. Retrieved on 12 April 2014.

- Pedro St. James | Grand Cayman, Grand Cayman Island | Cayman Islands Archived 12 January 2012 at the Wayback Machine. Caymanislands.ky. Retrieved on 12 April 2014.

- Stingray City | Grand Cayman, Grand Cayman Vacation | Cayman Islands Archived 1 May 2013 at the Wayback Machine. Caymanislands.ky. Retrieved on 12 April 2014.

- Tim Rock, Lonely Planet Diving & Snorkeling Cayman Islands (2nd edn, 2007, ISBN 1-74059-897-0), p. 99

- Kittiwake | Cayman Dive, Cayman Islands Vacation | Cayman Islands Archived 1 May 2013 at the Wayback Machine. Caymanislands.ky (5 January 2011). Retrieved on 12 April 2014.

- "Pirates Week Festival of the Cayman Islands". Piratesweekfestival.com. Archived from the original on 11 May 2021. Retrieved 13 May 2021.

- "National Trust For the Cayman islands". Nationaltrust.org.ky. Archived from the original on 7 August 2011. Retrieved 31 July 2011.

- Observation Tower | Camana Bay Archived 6 September 2014 at the Wayback Machine. CamanaBay.com. Retrieved on 1 August 2014.

- "CI shipping 2015/2016 annual report page 22" (PDF). cishipping.com. Archived from the original (PDF) on 27 July 2020. Retrieved 11 March 2019.

- "The Economics and Statistics Office". Government of the Cayman Islands. Archived from the original on 10 April 2021. Retrieved 3 April 2021.

- "Work Permit Stats". Eso.ky. 30 March 2007. Archived from the original on 22 July 2011. Retrieved 31 July 2011.

- "C.I. Government Website – Entry Requirements for Work Permits". Gov.ky. Archived from the original on 11 August 2022. Retrieved 31 July 2011.

- "Online Employment Resources". Island-search.com. Archived from the original on 10 August 2011. Retrieved 31 July 2011.

- Row brews over rollover, 22 January 2007, Cayman net News Archived 5 February 2009 at the Wayback Machine

- Government takes up permit issue Archived 14 September 2007 at the Wayback Machine, Editorial, 5 March 2006, Camanian Compass

- "Cayman Islands – Cay Compass News Online – Rollover for civil servants". Archived from the original on 6 March 2008. Retrieved 23 June 2008.

- "Cayman Observer". Archived from the original on 31 January 2017. Retrieved 23 June 2008.

- "CSME". immigration.gov.tt. Archived from the original on 26 March 2017. Retrieved 26 March 2017.

- "Country Profile for Cayman Islands — Caribbean Community (CARICOM)". caricom.org. Archived from the original on 21 June 2019. Retrieved 3 February 2019.

- "The Cayman Islands Constitution Order 2009" (PDF). legislation.gov.uk. 2009. Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 October 2022.

- "Commonwealth elections observers give Cayman Islands high marks". Caribbeannewsnow.com. Caribbean News Now. 27 May 2013. Archived from the original on 10 January 2014. Retrieved 28 May 2013.

The amendment of elections law in 2012 increased the number of elected members of the Parliament from fifteen to eighteen.

- Cayman Islands Constitution, 2009, part III article 49

- Cayman Islands Constitution, 2009, part II

- Constitution, articles 55 and 81

- Constitution article 78

- Constitution article 43

- Constitution article 35

- "Jane Owen - GOV.UK". gov.uk. Retrieved 22 April 2023.

- The Constitution of the Cayman Islands, Part VI The Legislature

- "Official Register of Political Parties" (PDF). Cayman Islands Elections Office. 29 August 2018. Archived from the original (PDF) on 29 August 2018. Retrieved 29 August 2018.

- "Premier McLaughlin to lead 13-member coalition government". Cayman Compass. 31 May 2017. Archived from the original on 29 August 2018. Retrieved 29 August 2018.

- "Police Service in the Cayman Islands". Royal Cayman Islands Police Service. Archived from the original on 18 March 2020. Retrieved 5 February 2020.

- "Home". Cayman Islands Customs & Border Control Service. Archived from the original on 2 February 2021. Retrieved 28 January 2021.

- Muckenfuss, Mark (14 October 2019). "Cayman regiment would provide disaster relief". Cayman Compass. Archived from the original on 14 October 2019. Retrieved 14 October 2019.

- "Cayman to set up its own regiment". Cayman Compass. 11 October 2019. Archived from the original on 12 October 2019. Retrieved 12 October 2019.

- "Cayman to create military regiment". Caymannewsservice.com. 11 October 2019. Archived from the original on 12 October 2019. Retrieved 12 October 2019.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 15 December 2019. Retrieved 15 December 2019.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - Ragoonath, Reshma (30 January 2020). "Regiment senior officers appointed". Cayman Compass. Archived from the original on 1 February 2020. Retrieved 5 February 2020.

- "The Cayman Island Cadet Corps - A Voluntary Youth Organization". Cicadetcorps.ky. Archived from the original on 6 February 2020. Retrieved 6 February 2020.

- Whittaker, James (29 August 2018). "Cayman's Coast Guard chiefs announced". Cayman Compass. Archived from the original on 18 November 2021. Retrieved 18 November 2021.

- "CIG unveils new border control and coast guard leaders". Caymannewsservice.com. 28 August 2018. Archived from the original on 8 December 2019. Retrieved 8 December 2019.

- "CICG Deployed in International Joint Operation". Cayman Islands Government. Archived from the original on 14 September 2019. Retrieved 5 February 2020.

- "Cayman Islands Coast Guard deployed in International Joint Operation". Ieyenews.com. 5 July 2019. Archived from the original on 9 February 2021. Retrieved 28 January 2021.

- "Coastguard to manage Stingray City". Caymannewsservice.com. 28 November 2019. Archived from the original on 28 November 2019. Retrieved 8 December 2019.

- "Cayman Islands Coast Guard Act (2021)" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 2 November 2021.

- "Cayman Islands History from 1700 to 1900". caymanresident.com. 16 December 2019. Archived from the original on 16 December 2019. Retrieved 16 December 2019.

- "United Kingdom / Europe / Member countries / Internet / Home – INTERPOL". Interpol.int. 30 December 2012. Archived from the original on 12 December 2012. Retrieved 30 December 2012.

- "Emergencies" (PDF). Travel.State.Gov U.S. Department of State — Bureau of Consular Affairs. 29 July 2018. Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 October 2022.

- "What We Do". Gov.ky. Archived from the original on 29 July 2018. Retrieved 29 July 2018.

- "Cayman Islands Cruise – Grand Cayman Island, Grand Cayman – Cayman Islands". Caymanislands.ky. Archived from the original on 1 May 2013. Retrieved 28 May 2013.

- "University College Cayman Islands: About us". Ucci.edu.ky. Archived from the original on 22 July 2011. Retrieved 31 July 2011.

- "International College of the Cayman islands: Programs of Study". Archived from the original on 1 January 2011.

- "St. Matthew's University". Stmatthews.edu. Archived from the original on 8 August 2011. Retrieved 31 July 2011.

- "Cayman Islands law School". Liv.ac.uk. Archived from the original on 14 January 2012. Retrieved 31 July 2011.

- "The Open Campus in Cayman Islands". University of the West Indies. Archived from the original on 24 February 2021. Retrieved 28 January 2021.

- "Moving to Cayman Islands : Sport!". Archived from the original on 28 March 2022. Retrieved 12 September 2021.

- FIBA National Federations – Cayman Islands Archived 11 May 2016 at the Wayback Machine, fiba.com, accessed 28 October 2015.

- "NatWest Island Games XVI Jersey 2015 Results – Sports – Swimming – Men's 200m Individual Medley". Jersey2015results.com. Archived from the original on 6 July 2015. Retrieved 30 June 2015.

- "International Cricket Council: Cayman Islands". Icc-cricket.yahoo.net. Archived from the original on 27 September 2011. Retrieved 31 July 2011.

- "An Informative guide of Black Pearl - Cayman Islands". Blackpearl.ky. Archived from the original on 31 March 2022. Retrieved 10 April 2022.

- "Black Pearl Skateboarding at the Grand Cayman Islands". Ieyenews.com. 31 January 2013. Archived from the original on 25 November 2020. Retrieved 7 December 2020.

- "Go-karting track up to speed" Archived 20 April 2010 at the Wayback Machine, Caymanian Compass, 23 February 2010

- "Parker's eased into top gear" Archived 2 February 2017 at the Wayback Machine, Caymanian Compass, 24 September 2010.

- "BIOGRAPHY CYDONIE CAMILLE MOTHERSILLE". Cayman Insider. Archived from the original on 7 February 2022. Retrieved 7 February 2022.

- "Cayman Festival and Events | Cultural Schedule". Artscayman.org. Archived from the original on 7 February 2018. Retrieved 4 February 2018.

- "Pop music from Cayman Islands". Online Radio Box. Archived from the original on 21 June 2018. Retrieved 21 June 2018.

- "Cayman Islands Government Directory". Gov.ky. Retrieved 10 April 2022.

- "About Us". National Gallery of the Cayman Islands. Archived from the original on 28 April 2020. Retrieved 25 November 2019.

- Wright, Jessica (11 January 2023). "Local News in the Cayman Islands: Print & Online". Cayman Resident. Retrieved 23 May 2023.

- Ragoonath, Reshma (20 May 2020). "Cayman mourns Olive Miller". Cayman Compass. Archived from the original on 16 May 2022. Retrieved 16 May 2022.

- "Olive Miller: Cayman's own Mother Teresa". Cayman Compass. 11 March 2014. Retrieved 16 May 2022.

- Quinnie110 (5 June 2009). "Cayman Went (2009)". IMDb.com. Archived from the original on 6 April 2017. Retrieved 1 July 2018.

- "Zombie Driftwood (2010)". IMDb.com. Archived from the original on 10 February 2017. Retrieved 1 July 2018.

- "Television in Cayman". caymanresident.com. Archived from the original on 1 October 2020. Retrieved 2 July 2021.

- "Internet Providers". caymanresident.com. Archived from the original on 1 October 2020. Retrieved 2 July 2021.

- Island Games Results Isle of Wight 2011 | Sports | Shooting | Olympic Skeet Individual – Men Archived 4 January 2012 at the Wayback Machine. Natwestiowresults2011.com. Retrieved on 12 April 2014.

Further reading

- Boultbee, Paul G. (1996). Cayman Islands. Oxford: ABC-Clio Press. ISBN 9781851092406. OCLC 35170772.

- "History of the Cayman Islands". Caribbean Magazine. Archived from the original on 11 May 2011. Retrieved 28 July 2010.

- "Cayman Islands". 2005 CIA World Factbook. Retrieved 4 July 2005. Originally from the CIA World Factbook 2000.

- Michael Craton and the New History Committee (2003). Founded upon the Seas: A History of the Cayman Islands and Their People. Kingston, Jamaica: Ian Randle Publishers. ISBN 0-9729358-3-5.

- "Non-Self-Governing Territories listed by General Assembly in 2002". United Nations Special Committee of 24 on Decolonization. Archived from the original on 3 December 2008. Retrieved 4 July 2005.

External links

- . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 5 (11th ed.). 1911.

- Cayman Islands Government

- Cayman Islands Department of Tourism

Wikimedia Atlas of Cayman Islands

Wikimedia Atlas of Cayman Islands- Cayman Islands Film Commission (archived 22 July 2011)

- Cayman Islands. The World Factbook. Central Intelligence Agency.

- Cayman Islands from UCB Libraries GovPubs (archived 7 April 2008)

- Cayman Islands at Curlie

- Cayman National Cultural Foundation