Australian English phonology

Australian English (AuE) is a non-rhotic variety of English spoken by most native-born Australians. Phonologically, it is one of the most regionally homogeneous language varieties in the world. Australian English is notable for vowel length contrasts which are absent from most English dialects.

The Australian English vowels /ɪ/, /e/, /eː/ and /oː/ are noticeably closer (pronounced with a higher tongue position) than their contemporary Received Pronunciation equivalents. However, a recent short-front vowel chain shift has resulted in younger generations having lower positions than this for the former three vowels.[1]

Vowels

| Phoneme | Lexical set | Phonetic realization | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cultivated | General | Broad | ||

| /iː/ | FLEECE | [ɪi] | [ɪ̈i] | [əːɪ] |

| /ʉː/ | GOOSE | [ʊu] | [ɪ̈ɯ, ʊʉ] | [əːʉ] |

| /æɪ/ | FACE | [ɛɪ] | [æ̠ɪ] | [æ̠ːɪ, a̠ːɪ] |

| /əʉ/ | GOAT | [ö̞ʊ] | [æ̠ʉ] | [æ̠ːʉ, a̠ːʉ] |

| /ɑɪ/ | PRICE | [a̠e] | [ɒe] | [ɒːe] |

| /æɔ/ | MOUTH | [a̠ʊ] | [æo] | [ɛːo, ɛ̃ːɤ] |

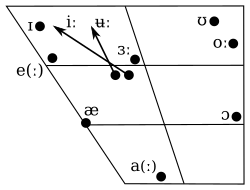

The vowels of Australian English can be divided according to length. The long vowels, which include monophthongs and diphthongs, mostly correspond to the tense vowels used in analyses of Received Pronunciation (RP) as well as its centring diphthongs. The short vowels, consisting only of monophthongs, correspond to the RP lax vowels. There exist pairs of long and short vowels with overlapping vowel quality giving Australian English phonemic length distinction.[3]

There are two families of phonemic transcriptions of Australian English: revised ones, which attempt to more accurately represent the phonetic sounds of Australian English; and the Mitchell-Delbridge system, which is minimally distinct from Jones' original transcription of RP. This page uses a revised transcription based on Durie and Hajek (1994) and Harrington, Cox and Evans (1997) but also shows the Mitchell-Delbridge equivalents as this system is commonly used for example in the Macquarie Dictionary and much literature, even recent.

| Front | Central | Back | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| short | long | short | long | short | long | |

| Close | ɪ | ʊ | oː | |||

| Mid | e | eː | ə | ɜː | ɔ | |

| Open | æ | (æː) | a | aː | ||

| Diphthongs | ɪə æɪ ɑɪ oɪ iː æɔ əʉ ʉː | |||||

- As with General American, the weak vowel merger is nearly complete in Australian English: unstressed /ɪ/ is merged with /ə/ (schwa) except before a following velar. New Zealand English takes it a step further and merges all instances of /ɪ/ with /ə/ (even in stressed syllables), which is why the New Zealand pronunciation of the dish name fish and chips as /ˈfəʃ ən ˈtʃəps/ sounds like 'fush and chups' to Australians.[4] In Australian English, /ə/ is restricted to unstressed syllables, as in most dialects.

- The trap-bath split is a regional variable in Australia, with the PALM vowel /aː/ being more common in South Australia than elsewhere. This is due to the fact that that state was settled later than the rest of Australia, when the lengthened pronunciation was already a feature of London speech. Research done by Crystal (1995) shows that the word graph is pronounced with the PALM vowel (/ɡɹaːf/) by 86% speakers from Adelaide, whereas 100% speakers from Hobart use the TRAP vowel in this word: /ɡɹæf/. There are words in which the TRAP vowel is much less common; for instance, Crystal reports that both the word grasp and the verb to contrast are most commonly pronounced with the PALM vowel: /ɡɹaːsp/, /kənˈtɹaːst/. This also affects the pronunciation of some placenames; Castlemaine is locally /ˈkæsəlmæɪn/, but speakers from outside of Victoria often pronounce that name /ˈkaːsəlmæɪn/ by analogy to the noun castle in their local accent.

Monophthongs

- The target for /ɪ/ is closer to cardinal [i] than in other dialects.[5] The aforementioned phrase fish and chips as pronounced by an Australian ([ˈfiʃ ən ˈtʃips] in narrow transcription) can sound a lot like feesh and cheeps to speakers of New Zealand English and other dialects, whereas words such as bit and sit may sound like beat and seat, respectively.

- The sound /ɪə/ is usually pronounced as a diphthong (or disyllabically [iːə], like CURE) only in open syllables. In closed syllables, it is distinguished from /ɪ/ primarily by length[6][7] and from /iː/ by the significant onset in the latter.

- /e/ tends to be higher than the corresponding vowel in General American or RP. The typical realization is close-mid [e], although for some speakers it may be even closer [e̝] (according to John Wells, this pronunciation can occur only in Broad varieties).[8][9] A recent change is the lowering of /e/ to the [ɛ] region.[8]

- For some Victorian speakers, /e/ has merged with /æ/ in pre-lateral environments, and thus the words celery and salary are homophonous as /ˈsæləɹiː/.[10] See salary-celery merger.

- The sound /æː/ is traditionally transcribed and analysed the same as the short /æ/, but minimal pairs exist in at least some Australians' speech.[11][6] It is found in the adjectives bad, mad, glad and sad, before the /ɡ/ sound (for example, hag, rag, bag) and also in content words before /m/ and /n/ in the same syllable (for example, ham, tan, plant).[12] In South Australia, plant is usually pronounced with the vowel sound /aː/, as in rather and father. In some speakers, especially those with the broad accent, /æː/ and /æ/ will be shifted toward [ɛː] and [ɛ], respectively.[13]

- There is æ-tensing before a nasal consonant. The nasal sounds create changes in preceding vowels because air can flow into the nose during the vowel. Nasal consonants can also affect the articulation of a vowel. Thus, for many speakers, the /æː/ vowel in words like jam, man, dam and hand is shifted towards [eː]. This is also present in General American and Cockney English.[14] Length has become the main difference between words like 'ban' and 'Ben', with 'ban' pronounced [beːn] and 'Ben' pronounced [ben].[15]

- /æ/ is pronounced as open front [a] by many younger speakers.[16]

- As with New Zealand English, the PALM/START vowel in words like park /paːk/, calm /kaːm/ and farm /faːm/ is central (in the past even front)[3] in terms of tongue position and non-rhotic. This is the same vowel sound used by speakers of the Boston accent of North Eastern New England in the United States. Thus the phrase park the car is said identically by a New Zealander, Australian or Bostonian.[17] This vowel is only distinguished from the STRUT vowel by length, thus: park /paːk/ versus puck /pak/.

- The phoneme /ɜː/ is pronounced at least as high as /eː/ ([ɘː]), and has a lowered F3 that might indicate that it is rounded [ɵː].[6][7] The ⟨ɜ⟩ glyph is used — rather than ⟨ɘ⟩ or ⟨ɵ⟩ — as most revisions of the phonemic orthography for Australian English predate the 1993 modifications to the International Phonetic Alphabet. At the time, ⟨ɜ⟩ was suitable for any mid central vowel, rounded or unrounded.

- The schwa /ə/ is a highly variable sound. For this reason, it is not shown on the vowel charts to the right. The word-final schwa in comma and letter is often lowered to [ɐ] so that it strongly resembles the STRUT vowel /a/: [ˈkɔmɐ, ˈleɾɐ]. As the latter is a checked vowel (meaning that it cannot occur in a final stressed position) and the lowering of /ə/ is not categorical (meaning that those words can be also pronounced [ˈsəʉfə] and [ˈbeɾə], whereas strut is never pronounced [stɹət]), this sound is considered to belong to the /ə/ phoneme.[18] The word-initial schwa (as in enduring /ənˈdʒʉːɹɪŋ/) is typically mid [ə]: [ənˈdʒʉːɹɪŋ]. In the word-internal position (as in bottom /ˈbɔtəm/), /ə/ is raised to [ɨ̞]: [ˈbɔɾɨ̞m], as in American English roses [ˈɹoʊzɨ̞z]. Thus, the difference between the /ə/ of paddock and the /ɪ/ of panic lies in the backness of the vowels, rather than their height: [ˈpædɨ̞k, ˈpænik].[19] In the rest of the article, those allophones of /ə/ are all transcribed with the broad symbol ⟨ə⟩: [ˈkɔmə] etc. /ɪ/ is also broadly transcribed with ⟨ɪ⟩: [ˈpænɪk], which does not capture its closeness.

Diphthongs

- The vowel /iː/ has an onset [ɪi̯], except before laterals.[10] The onset is often lowered to [əi], so that beat is [bəit] for some speakers.

- As in American English and modern RP, the final vowel in words like happy and city is pronounced as /iː/ (happee, citee), not as /ɪ/ (happy-tensing).[20]

- In some parts of Australia, a fully backed allophone of /ʉː/, transcribed [ʊː], is common before /l/. As a result, the pairs full/fool and pull/pool differ phonetically only in vowel length for those speakers.[6] The usual allophone is further forward in New South Wales than Victoria. It is moving further forwards, however, in both regions at a similar rate.[10]

- The second elements of /æɪ/ and /oɪ/ on the one hand and /ɑɪ/ on the other are somewhat different. The first two approach the KIT vowel /ɪ/, whereas the ending point of /ɑɪ/ is more similar to the DRESS vowel [e], which is why it tends to be written with ⟨ɑe⟩ in modern sources. John Wells writes this phoneme /ɑɪ/, with the same ending point as /æɪ/ and /oɪ/ (which he writes with ⟨ʌɪ⟩ and ⟨ɔɪ⟩). However, the second element of /ɑɪ/ is not nearly as different from that of the other fronting-closing diphthongs as the ending point of /æɔ/ is from that of /əʉ/, which is the reason why ⟨ɑɪ⟩ is used in this article.

- The first element of /ɑɪ/ may be raised and rounded in broad accents.

- The first element of /æɪ/ is significantly lower [a̠ɪ] than in many other dialects of English.

- There is significant allophonic variation in /əʉ/, including a backed allophone [ɔʊ] before a word-final or preconsonantal /l/. The first part of this allophone is in the same position as /ɔ/, but [ɔʊ] differs from it in that it possesses an additional closing glide, which also makes it longer than /ɔ/.

- /əʉ/ is shifted to [ɔy] among some speakers. This realisation has its roots in South Australia but is becoming more common among younger speakers across the country.[21]

- The phoneme /ʊə/ is rare and almost extinct. Most speakers consistently use [ʉːə] or [ʉː] (before /ɹ/) instead. Many cases of RP /ʊə/ are pronounced instead with the /oː/ phoneme in Australian English. "pour" and "poor", "more" and "moor" and "shore" and "sure" are homophones, but "tore" and "tour" remain distinct.

Examples of vowels

| Phoneme | Example words | Mitchell- Delbridge |

OED |

|---|---|---|---|

| /a/ | strut, bud, hud; cup | ʌ | ʌ |

| /aː/ | bath, palm, start, bard, hard; father | a | ʌː |

| /ɑɪ/ | price, bite, hide | aɪ | ɑe |

| /æ/ | trap, lad, had | æ | æ |

| /æː/ | bad, tan | æ | æ |

| /æɪ/ | face, bait, hade | eɪ | æe |

| /æɔ/ | mouth, bowed, how’d | aʊ | æɔ |

| /e/ | dress, bed, head | ɛ | e |

| /eː/ | square, bared, haired | ɛə | eə |

| /ɜː/ | nurse, bird, heard | ɜ | ɜː |

| /ə/ | about, winter; alpha | ə | ə |

| /əʉ/ | goat, bode, hoed | oʊ | oʊ |

| /ɪ/ | kit, bid, hid | ɪ | ɪ |

| /ɪə/ | near, beard, hear; here | ɪə | ɪə |

| /iː/ | fleece, bead, heat | i | iː |

| happy | i | ||

| /oː/ | thought, north, sure, board, hoard, poor; hawk, force | ɔ | ɔː |

| /oɪ/ | choice, boy; voice | ɔɪ | oɪ |

| /ɔ/ | lot, cloth, body, hot | ɒ | ɔ |

| /ʉː/ | goose, boo, who'd | u | uː |

| /ʊ/ | foot, hood | ʊ | ʊ |

- One needs to be very careful of the symbol /ɔ/, which represents different vowels: the LOT vowel in the Harrington, Cox and Evans (1997) system (transcribed /ɒ/ in the other system), but the THOUGHT vowel in the Mitchell-Delbridge system (transcribed /oː/ in the other system).[12]

- The fourth column is the OED transcription, taken from the OED website.[22]

It differs somewhat from the ad hoc Wikipedia transcription used in this article. In a few instances the OED example word differs from the others given in this table; these are appended at the end of the second column following a semicolon.

Consonants

Australian English consonants are similar to those of other non-rhotic varieties of English. A table containing the consonant phonemes is given below.

| Labial | Dental | Alveolar | Post- alveolar |

Palatal | Velar | Glottal | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nasal | m | n | ŋ | |||||

| Plosive | fortis | p | t | k | ||||

| lenis | b | d | ɡ | |||||

| Affricate | fortis | tʃ | ||||||

| lenis | dʒ | |||||||

| Fricative | fortis | f | θ | s | ʃ | h | ||

| lenis | v | ð | z | ʒ | ||||

| Approximant | central | ɹ | j | w | ||||

| lateral | l | |||||||

- Australian English is non-rhotic; in other words, the /ɹ/ sound does not appear at the end of a syllable or immediately before a consonant. So the words butter [ˈbaɾə], here [hɪə] and park [paːk] will not contain the /ɹ/ sound.[24]

- The [ɹ] sound can occur when a word that has a final ⟨r⟩ in the spelling comes before another word that starts with a vowel. For example, in car alarm the sound [ɹ] can occur in car because here it comes before another word beginning with a vowel. The words far, far more and farm do not contain an [ɹ] but far out will contain the linking [ɹ] sound because the next word starts with a vowel sound.

- An intrusive [ɹ] may be inserted before a vowel in words that do not have ⟨r⟩ in the spelling. For example, drawing will sound like draw-ring, saw it will sound like sore it, the tuner is and the tuna is will both be [ðə ˈtʃʉːnə.ɹɪz]. This [ɹ] occurs between /ə/, /oː/ and /aː/ and the following vowel regardless of the historical presence or absence of [ɹ]. Between /eː/, /ɜː/ and /ɪə/ (and /ʉːə/ whenever it stems from the earlier /ʊə/) and the following vowel, the [ɹ]-ful pronunciation is the historical one.

- Intervocalic /t/ (and for some speakers /d/) undergo voicing and flapping to the alveolar tap [ɾ] after the stressed syllable and before unstressed vowels (as in butter, party) and syllabic /l/ or /n/ (bottle [ˈbɔɾl̩], button [ˈbaɾn̩]), as well as at the end of a word or morpheme before any vowel (what else [wɔɾ‿ˈels], whatever [wɔɾˈevə]).[25] For those speakers where /d/ also undergoes the change, there will be homophony, for example, metal and medal or petal and pedal will sound the same ([ˈmeɾl̩] and [ˈpeɾl̩], respectively). In formal speech /t/ is retained. [t] in the cluster [nt] can elide. As a result, in quick speech, words like winner and winter can become homophonous (as [ˈwɪnə]). This is a quality that Australian English shares most notably with North American English.

- Some speakers use a glottal stop [ʔ] as an allophone of /t/ in final position, for example trait, habit; or in medial position, such as a /t/ followed by a syllabic /n/ is often realized as a glottal stop, for example button or fatten. Alveolar pronunciations nevertheless predominate.

- Pronunciation of /l/

- The alveolar lateral approximant /l/ is velarised [ɫ] in pre-pausal and preconsonantal positions and often also in morpheme-final positions before a vowel. There have been some suggestions that onset /l/ is also velarised, although that needs to be further researched. Some speakers vocalise preconsonantal, syllable-final and syllabic instances of /l/ to a close back vowel similar to /ʊ/, so that milk can be pronounced [mɪʊ̯k] and noodle [ˈnʉːdʊ]. This is more common in South Australia than elsewhere.[26]

- Standard Australian English usually coalesces /tj/ and /dj/ into /tʃ/ and /dʒ/ respectively. Because of this palatalisation, dune is pronounced as /dʒʉːn/, exactly like June, and the first syllable of Tuesday /ˈtʃʉːzdæɪ/ is pronounced like choose /tʃʉːz/. That said, there is stylistic and social variation in this feature. /t/ and /d/ in the clusters /tɹ/ and /dɹ/ are similarly affricated.[26]

- Word initial /sj/ and /zj/ have merged with /s/ and /z/ respectively. Other cases of /sj/ and /zj/ are often pronounced respectively [ʃ] and [ʒ], as in assume /əˈʃʉːm/ and resume /rəˈʒʉːm/ (ashume and rezhume).[27][28]

- Similarly, /lj/ has merged with /l/ word initially. Remaining cases of /lj/ are often pronounced simply as [j] in colloquial speech.

- /nj/ and other common sequences of consonant plus /j/, are retained.[26]

- For some speakers, /ʃ/ (or "sh") may be uttered instead of /s/ before the stressed /tj/ sound in words like student, history, eschew, street and Australia[29] – As a result, in quick speech, eschew will sound like esh-chew.[30] According to author Wayne P. Lawrence, "this phonemic change seems to be neither dialectal nor regional", as it can also be found among some American, Canadian, British and New Zealand English speakers as well.[31]

Other features

- Between voiced sounds, the glottal fricative /h/ may be realised as voiced [ɦ], so that e.g. behind may be pronounced as either [bəˈhɑɪnd] or [bəˈɦɑɪnd].[32]

- The sequence /hj/ is realised as a voiceless palatal fricative [ç], so that e.g. huge is pronounced [çʉːdʒ].[32]

- The word foyer is usually pronounced /ˈfoɪə/, as in NZ and American English, rather than /ˈfoɪeɪ/ as in British English.

- The word data is commonly pronounced /ˈdaːtə/, with /ˈdæɪtə/ being the second most common, and /ˈdætə/ being very rare.

- The trans- prefix is pronounced /tɹæns/, even in South Australia, where the trap–bath split is significantly more advanced than in other states.

- In English, upward inflexion (a rise in the pitch of the voice at the end of an utterance) typically signals a question. Some Australian English speakers commonly use a form of upward inflexion in their speech that is not associated with asking questions. Some speakers use upward inflexion as a way of including their conversational partner in the dialogue.[33] This is also common in Californian English.

Relationship to other varieties

Australian English pronunciation is most similar to that of New Zealand English; many people from other parts of the world often cannot distinguish them but there are differences. New Zealand English has centralised /ɪ/ and the other short front vowels are higher. New Zealand English more strongly maintains the diphthongal quality of the NEAR and SQUARE vowels and they can be merged as something around [iə]. New Zealand English does not have the bad-lad split, but like Victoria has merged /e/ with /æ/ in pre-lateral environments.

Both New Zealand English and Australian English are also similar to South African English, so they have even been grouped together under the common label "southern hemisphere Englishes".[34] Like the other two varieties in that group, Australian English pronunciation bears some similarities to dialects from the South-East of Britain;[35][36][37][38] Thus, it is non-rhotic and has the trap-bath split although, as indicated above, this split was not completed in Australia as it was in England, so many words that have the PALM vowel in Southeastern England retain the TRAP vowel in Australia.

Historically, the Australian English speaking manuals endorsed the lengthening of /ɔ/ before unvoiced fricatives however this has since been reversed. Australian English lacks some innovations in Cockney since the settling of Australia, such as the use of a glottal stop in many places where a /t/ would be found, th-fronting, and h-dropping. Flapping, which Australian English shares with New Zealand English and North American English, is also found in Cockney, where it occurs as a common alternative to the glottal stop in the intervocalic position. The word butter [ˈbaɾɐ] as pronounced by an Australian or a New Zealander can be homophonous with the Cockney pronunciation (which can be [ˈbaʔɐ] instead).

AusTalk

AusTalk is a database of Australian speech from all regions of the country.[39][40] Initially, 1000 adult voices were planned to be recorded in the period between June 2011 and June 2016. By the end of it, voices of 861 speakers with ages ranging from 18 to 83 were recorded into the database, each lasting approximately an hour. The database is expected to be expanded in future, to include children's voices and more variations. As well as providing a resource for cultural studies, the database is expected to help improve speech-based technology, such as speech recognition systems and hearing aids.[41]

The AusTalk database was collected as part of the Big Australian Speech Corpus (Big ASC) project, a collaboration between Australian universities and the speech technology experts.[42][43][44]

References

- Grama, James; Travis, Catherine E; González, Simón. "Initiation, progression, and conditioning of the short-front vowel shift in Australia". Academia. Retrieved 13 September 2023.

- Wells (1982), p. 597.

- Robert Mannell (2009-08-14). "Australian English – Impressionistic Phonetic Studies". Clas.mq.edu.au. Archived from the original on 6 July 2011. Retrieved 2011-07-26.

- Wells (1982), pp. 601, 606.

- "Distinctive Features". Clas.mq.edu.au. Retrieved 2011-07-26.

- Durie, M.; Hajek, J (1994), "A revised standard phonemic orthography for Australian English vowels", Australian Journal of Linguistics 14: 93–107

- Cox, Felicity (2006), "The acoustic characteristics of /hVd/ vowels in the speech of some Australian teenagers", Australian Journal of Linguistics 26: 147–179

- Cox & Fletcher (2017), pp. 65, 67.

- Wells (1982), p. 598.

- Cox & Palethorpe (2003).

- Blake, B. J. (1985), "'Short a' in Melbourne English", Journal of the International Phonetic Association 15: 6–20

- Robert Mannell and Felicity Cox (2009-08-01). "Phonemic (Broad) Transcription of Australian English (MD)". Clas.mq.edu.au. Retrieved 2011-07-26.

- Robert Mannell and Felicity Cox (2009-08-01). "Phonemic (Broad) Transcription of Australian English (HCE)". Clas.mq.edu.au. Archived from the original on 6 July 2011. Retrieved 2011-07-26.

- "further study | Australian Voices". Clas.mq.edu.au. 2010-07-29. Retrieved 2011-07-26.

- Cox, Felicity; Palethorpe, Sallyanne (2014). "Phonologisation of vowel duration and nasalised /æ/ in Australian English" (PDF). Proceedings of the 15th Australasian International Conference on Speech Science and Technology. pp. 33–36. Retrieved 2022-11-27.

- Cox & Fletcher (2017), p. 179.

- "The American Accents". 24 January 2011.

- Cox & Fletcher (2017), pp. 64, 163.

- Wells (1982), p. 601.

- "Australian voices".

- Cox & Fletcher (2017), p. 66.

- Catherine Sangester (2020-10-01). "Key to pronunciation: Australian English (OED)". public.oed.com. Retrieved 2021-10-25.

- Cox & Palethorpe (2007), p. 342.

- "studying speech | Australian Voices". Clas.mq.edu.au. 2010-07-29. Retrieved 2011-07-26.

- Tollfree (2001), pp. 57–8.

- Cox & Palethorpe (2007), p. 343.

- Wyld, H.C., A History of Modern Colloquial English, Blackwell 1936, cited in Wells (1982), p. 262.

- Wells (1982), p. 207.

- Durian, David (2007) "Getting [ʃ]tronger Every Day?: More on Urbanization and the Socio-geographic Diffusion of (str) in Columbus, OH," University of Pennsylvania Working Papers in Linguistics: Vol. 13: Iss. 2, Article 6

- Cole, J., Hualde, J.I., Laboratory Phonology 9, Walter de Gruyter 2007, p. 69.

- Lawrence, Wayne P. (2000) "Assimilation at a Distance," American Speech Vol. 75: Iss. 1: 82-87; doi:10.1215/00031283-75-1-82

- Cox & Fletcher (2017), p. 159.

- "audio illustrations | Australian Voices". Clas.mq.edu.au. 2010-07-29. Retrieved 2011-10-17.

- Gordon, Elizabeth and Andrea Sudbury. 2002. The history of southern hemisphere Englishes. In: Richard J. Watts and Peter Trudgill. Alternative Histories of English. P.67

- Gordon, Elizabeth and Andrea Sudbury. 2002. The history of southern hemisphere Englishes. In: Richard J. Watts and Peter Trudgill. Alternative Histories of English. P.79

- Wells (1982), p. 595.

- Gordon, Elizabeth. New Zealand English: its origins and evolution. 2004. P.82

- Hammarström, Göran. 1980. Australian English: its origin and status. passim

- Kate Wild (1 March 2015). "Austalk Australian accent research: National study aims to capture accented English spoken by Aboriginal Territorians". Australian Broadcasting Corporation. Retrieved 1 March 2015.

- "Aussie accent recorded for history for Australia Day". News Limited. 26 January 2011. Retrieved 1 March 2015.

- "AusTalk: An audio-visual corpus of Australian English". AusTalk. Retrieved 1 March 2015.

- "Publications and presentations". Archived from the original on 26 February 2015. Retrieved 1 March 2015.

- "About AusTalk". AusTalk. Archived from the original on 26 February 2015. Retrieved 1 March 2015.

- Estival, Dominique; Cassidy, Steve; Cox, Felicity; Burnham, Denis, AusTalk: an audio-visual corpus of Australian English (PDF), archived from the original (PDF) on 26 February 2015, retrieved 1 March 2015

Bibliography

- Blake, B. J. (1985), "'Short a' in Melbourne English", Journal of the International Phonetic Association, 15: 6–20, doi:10.1017/S0025100300002899, S2CID 145558284

- Cox, Felicity (2006), "The acoustic characteristics of /hVd/ vowels in the speech of some Australian teenagers", Australian Journal of Linguistics, 26 (2): 147–179, doi:10.1080/07268600600885494, S2CID 62226994

- Cox, Felicity; Fletcher, Janet (2017) [First published 2012], Australian English Pronunciation and Transcription (2nd ed.), Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-1-316-63926-9

- Cox, Felicity; Palethorpe, Sallyanne (2003), "The border effect: Vowel differences across the NSW–Victorian Border", Proceedings of the 2003 Conference of the Australian Linguistic Society: 1–14

- Cox, Felicity; Palethorpe, Sallyanne (2007), "Australian English" (PDF), Journal of the International Phonetic Association, 37 (3): 341–350, doi:10.1017/S0025100307003192

- Crystal, D. (1995), Cambridge Encyclopedia of the English Language, Cambridge University Press

- Durie, M.; Hajek, J (1994), "A revised standard phonemic orthography for Australian English vowels", Australian Journal of Linguistics, 14: 93–107, doi:10.1080/07268609408599503.

- Harrington, J.; Cox, Felicity; Evans, Z. (1997), "An acoustic phonetic study of broad, general, and cultivated Australian English vowels", Australian Journal of Linguistics, 17 (2): 155–84, doi:10.1080/07268609708599550

- Palethorpe, S. and Cox, F. M. (2003) Vowel Modification in Pre-lateral Environments. Poster presented at the International Seminar on Speech Production, December 2003, Sydney.

- Tollfree, Laura (2001), "Variation and change in Australian consonants: reduction of /t/", in Blair, David; Collins, Peter (eds.), English in Australia, John Benjamins, pp. 45–67, doi:10.1075/veaw.g26.06tol, ISBN 90-272-4884-2

- Wells, John C. (1982), Accents of English, Vol. 1: An Introduction (pp. i–xx, 1–278), Vol. 3: Beyond the British Isles (pp. i–xx, 467–674), Cambridge University Press, ISBN 0-52129719-2, 0-52128541-0

Further reading

- Bauer, Laurie (2015), "Australian and New Zealand English", in Reed, Marnie; Levis, John M. (eds.), The Handbook of English Pronunciation, Malden, MA: John Wiley & Sons, pp. 269–285, ISBN 978-1-118-31447-0

- Jilka, Matthias. "Australian English and New Zealand English" (PDF). Stuttgart: Institut für Linguistik/Anglistik, University of Stuttgart. Archived from the original (PDF) on 21 April 2014.

- Turner, George W. (1994), "6: English in Australia", in Burchfield, Robert (ed.), The Cambridge History of the English Language, vol. 5: English in Britain and Overseas: Origins and Development, Cambridge University Press, pp. 277–327, ISBN 978-0-521-26478-5

External links

- "Mapping Words Around Australia". The Linguistics Roadshow. 2015-11-09. Retrieved 2023-08-15.