Voiced dental fricative

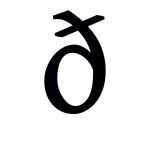

The voiced dental fricative is a consonant sound used in some spoken languages. It is familiar to English-speakers as the th sound in father. Its symbol in the International Phonetic Alphabet is eth, or ⟨ð⟩ and was taken from the Old English and Icelandic letter eth, which could stand for either a voiced or unvoiced (inter)dental non-sibilant fricative. Such fricatives are often called "interdental" because they are often produced with the tongue between the upper and lower teeth (as in Received Pronunciation), and not just against the back of the upper teeth, as they are with other dental consonants.

| Voiced dental fricative | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| ð | |||

| IPA Number | 131 | ||

| Audio sample | |||

|

source · help | |||

| Encoding | |||

| Entity (decimal) | ð | ||

| Unicode (hex) | U+00F0 | ||

| X-SAMPA | D | ||

| Braille | |||

| |||

| Voiced dental approximant | |

|---|---|

| ð̞ | |

| ɹ̪ | |

| Audio sample | |

|

source · help |

The letter ⟨ð⟩ is sometimes used to represent the dental approximant, a similar sound, which no language is known to contrast with a dental non-sibilant fricative,[1] but the approximant is more clearly written with the lowering diacritic: ⟨ð̞⟩. Very rarely used variant transcriptions of the dental approximant include ⟨ʋ̠⟩ (retracted [ʋ]), ⟨ɹ̟⟩ (advanced [ɹ]) and ⟨ɹ̪⟩ (dentalised [ɹ]). It has been proposed that either a turned ⟨ð⟩[2] or reversed ⟨ð⟩[3] be used as a dedicated symbol for the dental approximant, but despite occasional usage, this has not gained general acceptance.

The fricative and its unvoiced counterpart are rare phonemes. Almost all languages of Europe and Asia, such as German, French, Persian, Japanese, and Mandarin, lack the sound. Native speakers of languages without the sound often have difficulty enunciating or distinguishing it, and they replace it with a voiced alveolar sibilant [z], a voiced dental stop or voiced alveolar stop [d], or a voiced labiodental fricative [v]; known respectively as th-alveolarization, th-stopping, and th-fronting. As for Europe, there seems to be a great arc where the sound (and/or its unvoiced variant) is present. Most of Mainland Europe lacks the sound. However, some "periphery" languages such as Gascon, Welsh, English, Elfdalian, Kven, Northern Sámi, Inari Sámi, Skolt Sámi, Ume Sámi, Mari, Greek, Albanian, Sardinian, Aromanian, some dialects of Basque and most speakers of Spanish have the sound in their consonant inventories, as phonemes or allophones.

Within Turkic languages, Bashkir and Turkmen have both voiced and voiceless dental non-sibilant fricatives among their consonants. Among Semitic languages, they are used in Modern Standard Arabic, albeit not by all speakers of modern Arabic dialects, and in some dialects of Hebrew and Assyrian.

Features

Features of the voiced dental non-sibilant fricative:

- Its manner of articulation is fricative, which means it is produced by constricting air flow through a narrow channel at the place of articulation, causing turbulence. It does not have the grooved tongue and directed airflow, or the high frequencies, of a sibilant.

- Its place of articulation is dental, which means it is articulated with either the tip or the blade of the tongue at the upper teeth, termed respectively apical and laminal. Note that most stops and liquids described as dental are actually denti-alveolar.

- Its phonation is voiced, which means the vocal cords vibrate during the articulation.

- It is an oral consonant, which means air is allowed to escape through the mouth only.

- It is a central consonant, which means it is produced by directing the airstream along the center of the tongue, rather than to the sides.

- The airstream mechanism is pulmonic, which means it is articulated by pushing air solely with the intercostal muscles and diaphragm, as in most sounds.

Occurrence

In the following transcriptions, the undertack diacritic may be used to indicate an approximant [ð̞].

| Language | Word | IPA | Meaning | Notes | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Albanian | idhull | [iðuɫ] | 'idol' | ||

| Aleut[4] | damo | [ðɑmo] | 'house' | ||

| Arabic | Modern Standard[5] | ذهب | [ˈðahab] | 'gold' | See Arabic phonology |

| Gulf | |||||

| Najdi | |||||

| Tunisian | See Tunisian Arabic phonology | ||||

| Aromanian[6] | zală | [ˈðalə] | 'butter whey' | Corresponds to [z] in standard Romanian. See Romanian phonology | |

| Assyrian | ܘܪܕܐ werda | [wεrð̞a] | 'flower' | Common in the Tyari, Barwari, and Western dialects. Corresponds to [d] in other varieties. | |

| Asturian | Some dialects | fazer | [fäˈðeɾ] | 'to do' | Alternative realization of etymological ⟨z⟩. Can also be realized as [θ]. |

| Bashkir | ҡаҙ / qað | ⓘ | 'goose' | ||

| Basque[7] | adar | [að̞ar] | 'horn' | Allophone of /d/ | |

| Berta | [fɛ̀ːðɑ̀nɑ́] | 'to sweep' | |||

| Burmese[8] | အညာသား | [ʔəɲàd̪͡ðá] | 'inlander' | Commonly realized as an affricate [d̪͡ð].[9] | |

| Catalan[10] | cada | [ˈkɑðɐ] | 'each' | Fricative or approximant. Allophone of /d/. See Catalan phonology | |

| Cree | Woods Cree (th-dialect) | nitha | [niða] | 'I' | Reflex of Proto-Algonguian *r. Shares features of a sonorant. |

| Dahalo[11] | Weak fricative or approximant. It is a common intervocalic allophone of /d̪/, and may be simply a plosive [d̪] instead.[11] | ||||

| Elfdalian | baiða | [ˈbaɪða] | 'wait' | ||

| Emilian | Bolognese | żänt | [ðæ̃:t] | 'people' | |

| English | Received Pronunciation[12] | this | [ðɪs] | 'this' | |

| Western American English | ⓘ | Interdental.[12] | |||

| Extremaduran | ḥazel | [häðel] | 'to do' | Realization of etymological 'z'. Can also be realized as [θ] | |

| Fijian | ciwa | [ðiwa] | 'nine' | ||

| Galician | Some dialects[13] | fazer | [fɐˈðeɾ] | 'to do' | Alternative realization of etymological ⟨z⟩. Can also be realized as [θ, z, z̺]. |

| German | Austrian[14] | leider | [ˈlaɛ̯ða] | 'unfortunately' | Intervocalic allophone of /d/ in casual speech. See Standard German phonology |

| Greek | δάφνη / dáfni | [ˈðafni] | 'laurel' | See Modern Greek phonology | |

| Gwich’in | niidhàn | [niːðân] | 'you want' | ||

| Hän | ë̀dhä̀ | [ə̂ðɑ̂] | 'hide' | ||

| Harsusi | [ðebeːr] | 'bee' | |||

| Hebrew | Iraqi | אדוני | ⓘ | 'my lord' | Commonly pronounced [d]. See Modern Hebrew phonology |

| Judeo-Spanish | Many dialects | קריאדֿור / kriador | [kɾiaˈðor] | 'creator' | Intervocalic allophone of /d/ in many dialects. |

| Kabyle | ḏuḇ | [ðuβ] | 'to be exhausted' | ||

| Kagayanen[15] | kalag | [kað̞aɡ] | 'spirit' | ||

| Kurdish | An approximant; postvocalic allophone of /d/. See Kurdish phonology. | ||||

| Malay | Malaysian | azan | [a.ðan] | 'azan' | Only in Arabic loanwords; usually replaced with /z/. See Malay phonology |

| Malayalam | 'അത്' | [aðɨ̆] | 'That' | Colloquial usage. | |

| Mari | Eastern dialect | шодо | [ʃoðo] | 'lung' | |

| Norman | Jèrriais | méthe | [mɛð] | 'mother' | Predominantly found in western Jèrriais dialects; otherwise realised as [ɾ], and sometimes as [l] or [z]. |

| Northern Sámi | dieđa | [d̥ieðɑ] | 'science' | ||

| Norwegian | Meldal dialect[16] | i | [ð̩ʲ˕ː] | 'in' | Syllabic palatalized frictionless approximant[16] corresponding to /iː/ in other dialects. See Norwegian phonology |

| Occitan | Gascon | que divi | [ke ˈð̞iwi] | 'what I should' | Allophone of /d/. See Occitan phonology |

| Portuguese | European[17] | nada | [ˈn̪äðɐ] | 'nothing' | Northern and central dialects. Allophone of /d/, mainly after an oral vowel.[18] See Portuguese phonology |

| Sardinian | nidu | ⓘ | 'nest' | Allophone of /d/ | |

| Scottish Gaelic | Lewis and South Uist | Màiri | [ˈmaːðɪ] | 'Mary' | Hebridean realisation of /ɾʲ/, particularly common in Lewis and South Uist; otherwise realized as [ɾʲ][19] or as [r̝] in southern Barra and Vatersay. |

| Sioux | Lakota | zapta | [ˈðaptã] | 'five' | Sometimes with [z] |

| Spanish | Most dialects[20] | dedo | [ˈd̪e̞ð̞o̞] | 'finger' | Ranges from close fricative to approximant.[21] Allophone of /d/. See Spanish phonology |

| Swahili | dhambi | [ðɑmbi] | 'sin' | Mostly occurs in Arabic loanwords originally containing this sound. | |

| Swedish | Central Standard[22] | bada | [ˈbɑːð̞ä] | 'to take a bath' | An approximant;[22] allophone of /d/ in casual speech. See Swedish phonology |

| Some dialects[16] | i | [ð̩ʲ˕ː] | 'in' | A syllabic palatalized frictionless approximant[16] corresponding to /iː/ in Central Standard Swedish. See Swedish phonology | |

| Syriac | Western Neo-Aramaic | ܐܚܕ | [aħːeð] | 'to take' | |

| Tamil | ஒன்பது | [wʌnbʌðɯ] | 'nine' | See Tamil phonology | |

| Tanacross | dhet | [ðet] | 'liver' | ||

| Tutchone | Northern | edhó | [eðǒ] | 'hide' | |

| Southern | adhǜ | [aðɨ̂] | |||

| Venetian | mezorno | [meˈðorno] | 'midday' | ||

| Welsh | bardd | [barð] | 'bard' | See Welsh phonology | |

| Zapotec | Tilquiapan[23] | Allophone of /d/ | |||

Danish [ð] is actually a velarized alveolar approximant.[24][25]

See also

Notes

- Olson et al. (2010:210)

- Kenneth S. Olson, Jeff Mielke, Josephine Sanicas-Daguman, Carol Jean Pebley & Hugh J. Paterson III, 'The phonetic status of the (inter)dental approximant', Journal of the International Phonetic Association, Vol. 40, No. 2 (August 2010), pp. 201–211

- Ball, Martin J.; Howard, Sara J.; Miller, Kirk (2018). "Revisions to the extIPA chart". Journal of the International Phonetic Association. 48 (2): 155–164. doi:10.1017/S0025100317000147. S2CID 151863976.

- "damo in English - Aleut-English Dictionary | Glosbe". glosbe.com. Retrieved 2023-07-24.

- Thelwall & Sa'Adeddin (1990:37)

- Pop (1938), p. 30.

- Hualde (1991:99–100)

- Watkins (2001:291–292)

- Watkins (2001:292)

- Carbonell & Llisterri (1992:55)

- Maddieson et al. (1993:34)

- Ladefoged & Maddieson (1996), p. 143.

- "Atlas Lingüístico Gallego (ALGa) | Instituto da Lingua Galega - ILG". ilg.usc.es. 14 October 2013. Retrieved 2019-11-25.

- Sylvia Moosmüller (2007). "Vowels in Standard Austrian German: An Acoustic-Phonetic and Phonological Analysis" (PDF). p. 6. Retrieved March 9, 2013.

- Olson et al. (2010:206–207)

- Vanvik (1979:14)

- Cruz-Ferreira (1995:92)

- Mateus & d'Andrade (2000:11)

- "Slender 'r'/ 'an t-s'".

- Martínez-Celdrán, Fernández-Planas & Carrera-Sabaté (2003:255)

- Phonetic studies such as Quilis (1981) have found that Spanish voiced stops may surface as spirants with various degrees of constriction. These allophones are not limited to regular fricative articulations, but range from articulations that involve a near complete oral closure to articulations involving a degree of aperture quite close to vocalization

- Engstrand (2004:167)

- Merrill (2008:109)

- Grønnum (2003:121)

- Basbøll (2005:59, 63)

References

- Basbøll, Hans (2005), The Phonology of Danish, OUP Oxford, ISBN 0-19-824268-9

- Carbonell, Joan F.; Llisterri, Joaquim (1992), "Catalan", Journal of the International Phonetic Association, 22 (1–2): 53–56, doi:10.1017/S0025100300004618, S2CID 249411809

- Cotton, Eleanor Greet; Sharp, John (1988), Spanish in the Americas, Georgetown University Press, ISBN 978-0-87840-094-2

- Cruz-Ferreira, Madalena (1995), "European Portuguese", Journal of the International Phonetic Association, 25 (2): 90–94, doi:10.1017/S0025100300005223, S2CID 249414876

- Engstrand, Olle (2004), Fonetikens grunder (in Swedish), Lund: Studenlitteratur, ISBN 91-44-04238-8

- Grønnum, Nina (2003), "Why are the Danes so hard to understand?", in Jacobsen, Henrik Galberg; Bleses, Dorthe; Madsen, Thomas O.; Thomsen, Pia (eds.), Take Danish - for instance: linguistic studies in honour of Hans Basbøll, presented on the occasion of his 60th birthday, Odense: Syddansk Universitetsforlag, pp. 119–130

- Hualde, José Ignacio (1991), Basque phonology, New York: Routledge, ISBN 978-0-415-05655-7

- Ladefoged, Peter; Maddieson, Ian (1996), The Sounds of the World's Languages, Oxford: Blackwell, ISBN 978-0-631-19815-4

- Maddieson, Ian; Spajić, Siniša; Sands, Bonny; Ladefoged, Peter (1993), "Phonetic structures of Dahalo", in Maddieson, Ian (ed.), UCLA working papers in phonetics: Fieldwork studies of targeted languages, vol. 84, Los Angeles: The UCLA Phonetics Laboratory Group, pp. 25–65

- Martínez-Celdrán, Eugenio; Fernández-Planas, Ana Ma.; Carrera-Sabaté, Josefina (2003), "Illustrations of the IPA: Castilian Spanish" (PDF), Journal of the International Phonetic Association, 33 (2): 255–259, doi:10.1017/S0025100303001373

- Mateus, Maria Helena; d'Andrade, Ernesto (2000), The Phonology of Portuguese, Oxford University Press, ISBN 0-19-823581-X

- Merrill, Elizabeth (2008), "Tilquiapan Zapotec" (PDF), Journal of the International Phonetic Association, 38 (1): 107–114, doi:10.1017/S0025100308003344

- Olson, Kenneth; Mielke, Jeff; Sanicas-Daguman, Josephine; Pebley, Carol Jean; Paterson, Hugh J., III (2010), "The phonetic status of the (inter)dental approximant", Journal of the International Phonetic Association, 40 (2): 199–215, doi:10.1017/S0025100309990296, S2CID 38504322

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Pop, Sever (1938), Micul Atlas Linguistic Român, Muzeul Limbii Române Cluj

- Quilis, Antonio (1981), Fonética acústica de la lengua española [Acoustic phonetics of the Spanish language] (in Spanish), Gredos, ISBN 9788424901318

- Thelwall, Robin; Sa'Adeddin, M. Akram (1990), "Arabic", Journal of the International Phonetic Association, 20 (2): 37–41, doi:10.1017/S0025100300004266, S2CID 249416512

- Vanvik, Arne (1979), Norsk fonetikk [Norwegian phonetics] (in Norwegian), Oslo: Universitetet i Oslo, ISBN 82-990584-0-6

- Watkins, Justin W. (2001), "Illustrations of the IPA: Burmese" (PDF), Journal of the International Phonetic Association, 31 (2): 291–295, doi:10.1017/S0025100301002122, S2CID 232344700