Ume Sámi

Ume Sámi (Ume Sami: Ubmejesámiengiälla, Norwegian: Umesamisk, Swedish: Umesamiska) is a Sámi language spoken in Sweden and formerly in Norway. It is a moribund language with an estimated 100 speakers. It was spoken mainly along the Ume River in the south of present-day Arjeplog, in Sorsele and in Arvidsjaur.[2][3]

| Ume Sámi | |

|---|---|

| ubmejesámiengiälla | |

| Native to | Sweden |

Native speakers | 100 (2000)[1] |

| Latin | |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-3 | sju |

| Glottolog | umes1235 |

| ELP | Ume Saami |

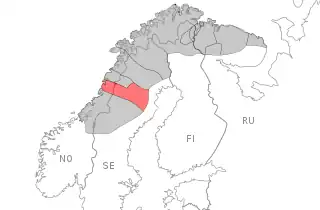

Ume Sami language area (red) within Sápmi (grey) | |

Ume Saami is classified as Critically Endangered by the UNESCO Atlas of the World's Languages in Danger | |

Dialects

The best-known variety of Ume Sami is that of one Lars Sjulsson (born 1871) from Setsele, close to Malå, whose idiolect was documented by W. Schlachter in a 1958 dictionary and subsequent work.[4] Dialect variation exists within the Ume Sami area, however. A main division is between more (north)western dialects such as those of Maskaure, Tärna and Ullisjaure (typically agreeing with Southern Sami), versus more (south)eastern dialects such as those of Malå, Malmesjaure and Mausjaure (typically agreeing with Pite Sami).[5]

| Feature | Western Ume Sami | Eastern Ume Sami | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| original *ðː | /rː/ | /ðː/ | |

| accusative singular ending | -p | -w | from Proto-Samic *-m |

| word for 'eagle' | (h)àrʰčə | àrtnəs |

Phonology

Consonants

| Labial | Dental/ Alveolar |

Post- alveolar |

Velar | Glottal | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nasal | m | n | ɲ | ŋ | ||

| Plosive | p | t | k | |||

| Affricate | t͡s | t͡ʃ | ||||

| Fricative | voiceless | v | s | ʃ | h | |

| voiced | ð | |||||

| Trill | r | |||||

| Approximant | l | j | ||||

[f, ʋ] and [θ] are allophones of /v/ and /ð/, respectively. When a /h/ sound occurs before a plosive or an affricate sound, they are then realized as preaspirated sounds. If an /l/ sound occurs before a /j/ sound, it is realized as a palatal lateral [ʎ] sound. Some western dialects of the language lack the /ð/ phoneme.

Writing system

Until 2010, Ume Sámi did not have an official written standard, although it was the first Sámi language to be written extensively (because a private Christian school for Sámi children started in Lycksele 1632, where Ume Sámi was spoken). The New Testament was published in Ume Sámi in 1755 and the first Bible in Sámi was also published in Ume Sámi, in 1811.

The current official orthography is maintained by the Working Group for Ume Sámi, whose most recent recommendation was published in 2016.

| Letter | Phoneme(s) |

|---|---|

| A a | /ʌ/ |

| Á á | /ɑː/ |

| B b | /p/ |

| D d | /t/ |

| Đ đ | /ð/ |

| E e | /e/, /eː/ |

| F f | /f/ |

| G g | /k/ |

| H h | /h/ |

| I i | /i/ |

| Ï ï | /ɨ/ |

| J j | /j/ |

| K k | /hk/, /k/ |

| L l | /l/ |

| M m | /m/ |

| N n | /n/ |

| Ŋ ŋ | /ŋ/ |

| O o | /o/ (only in diphthongs) |

| P p | /hp/, /p/ |

| R r | /r/ |

| S s | /s/ |

| T t | /ht/, /t/ |

| Ŧ ŧ | /θ/ |

| U u | /u/, /uː/ |

| Ü ü | /ʉ/, /ʉː/ |

| V v | /v/ |

| Y y | /y/ |

| Å å | /o/, /ɔː/ |

| Ä ä | /ɛː/ |

| Ö ö | /œ/ (only in diphthongs) |

Shortcomings:

- Vowel length is ambiguous for the letters ⟨u⟩, ⟨ü⟩ and ⟨å⟩. In reference works, the length is indicated by a macron (⟨ū⟩, ⟨ǖ⟩, ⟨å̄⟩). In older orthographies, length could be indicated by writing a double vowel.

- No distinction is made between long and overlong consonants, both being written with a double consonant letter. In reference works, the overlong stops are indicated with a vertical line (⟨bˈb⟩, ⟨dˈd⟩ etc.)

Grammar

Consonant gradation

Unlike its southern neighbor Southern Sámi, Ume Sámi has consonant gradation. However, gradation is more limited than it is in the more northern Sami languages, because it does not occur in the case of short vowels followed by a consonant that can gradate to quantity 1 (that is, Proto-Samic single consonants or geminates). In these cases, only quantity 3 appears. Consonant clusters can gradate regardless of the preceding vowel.

Cases

Ume Sámi has 8 cases:[7]

- Nominative

- Accusative

- Genitive

- Illative

- Inessive

- Elative

- Comitative

- Essive

Persons and numbers

The verbs in Ume Sámi have three persons, first, second and third. There are three grammatical numbers: singular, dual and plural.

Mood

Ume Sámi has two grammatical moods: indicative and imperative

Negative verb

Ume Sámi, like Finnish, the other Sámi languages, and Estonian, has a negative verb. In Ume Sámi, the negative verb conjugates according to mood (indicative and imperative), person (1st, 2nd and 3rd) and number (singular, dual and plural).

Example

| Transcription | Swedish translation | English translation |

| Båtsuoj-bieŋjuv galggá báddie-gietjiesna álggiet lieratit. De tjuavrrá jiehtja viegadit ráddiesta ráddáje jah nav ájaj livva-sijiesna, guh jiehtják súhph. Die galggá daina báddie-bieŋjijne viegadit bijrra ieluon, nav júhtie biegŋja galggá vuöjdniet gúktie almatjh gelggh dahkat. Lierruo-biegŋja daggár bälij vánatallá ieluon bijrra ja ij akttak bijgŋuolissa luöjtieh. Die måddie bálliena daggár biegŋja, juhka ij leäh ållást lieratuvvama, die butsijda válldá ja dulvada. De daggár bälij tjuavrrá suv báddáje válldiet jah slåvvat. |

Renhunden ska man börja lära i koppel. Då måste man själv springa från den ena kanten till den andra (av renhjorden) och så också på (renarnas) viloplats, medan de andra äter. Då ska man med den där bandhunden springa runt hjorden, så att hunden ser, hur folket gör. Lärohunden springer en sådan gång runt hjorden och låter ingen undslippa. Så finns det ofta sådana hundar, som inte har lärt sig helt, som tar någon ren och jagar iväg den. Då måste man en sådan gång sätta band på den och slå den. |

A reindeer herding dog must begin its training with a leash. Then one has to run from one side [of the herd] to the other and also on the area where they [the reindeer] rest, while others are eating. One must run around the herd with the dog [to be trained] on a leash, so that the dog sees how people do it. The trained dog then runs around the herd and does not allow any to slip away. Then there are often dogs that are not fully trained [and] who single out a reindeer and drive it away [i.e. to kill it]. Then one must put a leash on that [dog] and strike it. |

See also

References

- Ume Sámi at Ethnologue (18th ed., 2015) (subscription required)

- Korhonen, Olavi (2005). "Ume Saami language". The Saami: a cultural encyclopaedia. Helsinki. pp. 421–422. ISBN 9789517465069.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Pekka Sammallahti, The Saami languages: an introduction, Kárášjohka, 1998

- Schlachter, Wolfgang (1958). Wörterbuch des Waldlappendialekts von Malå und Texte zur Ethnographie. Helsinki: Suomalais-Ugrilainen Seura.

- Larsson, Lars-Gunnar (2010). "Ume Saami language variation". Congressus XI Internationalis Fenno-Ugristarum. Piliscsaba 2010. Pars I. Orationes plenares. Piliscsaba. pp. 193–224.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - von Gertten, Daniel (2015). Huvuddrag i umesamisk grammatik. University of Oslo.

- Korhonen Olavi & Barruk Henrik, 2010, Kurs i umesamiska (2010‑02‑07)

External links

- Sámi lottit Names of birds found in Sápmi in a number of languages, including Skolt Sámi and English. Search function only works with Finnish input though.

.png.webp)