Khanty language

Khanty (also spelled Khanti or Hanti), previously known as Ostyak (/ˈɒstiæk/),[3] is a Uralic language spoken in the Khanty-Mansi and Yamalo-Nenets Okrugs. There were thought to be around 7,500 speakers of Northern Khanty and 2,000 speakers of Eastern Khanty in 2010, with Southern Khanty being extinct since the early 20th century,[4] however the total amount of speakers in the most recent census was around 13,900.[5][6]

| Khanty | |

|---|---|

| ханты ясаң hantĭ jasaŋ | |

| Native to | Russia |

| Region | Khanty–Mansi |

| Ethnicity | 31,467 Khanty people (2020 census)[1] |

Native speakers | 14,000 (2020 census)[2] |

| Dialects |

|

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-3 | kca |

| Glottolog | khan1279 |

| ELP | |

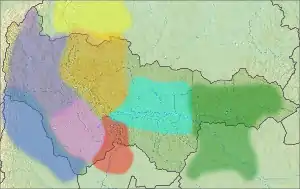

The Khanty language has many dialects. The western group includes the Obdorian, Ob, and Irtysh dialects. The eastern group includes the Surgut and Vakh-Vasyugan dialects, which, in turn, are subdivided into thirteen other dialects. All these dialects differ significantly from each other by phonetic, morphological, and lexical features to the extent that the three main "dialects" (northern, southern and eastern) are mutually unintelligible.[7] Thus, based on their significant multifactorial differences, Eastern, Northern and Southern Khanty could be considered separate but closely related languages.

Alphabet

| А а | Ӑ ӑ | В в | Е е | Ё ё | Ә ә | И и | Й й |

| К к | Л л | Ԯ ԯ | М м | Н н | Ң ң | О о | П п |

| Р р | С с | Т т | У у | Ў ў | Х х | Ш ш | Щ щ |

| Ь ь | Ы ы | Э э | Ю ю | Я я |

Palatalised consonants are designated by either ь or a yotated character.[8]

| Cyrillic | А а | Ӑ ӑ | В в | Е е | Ё ё | Ә ә | И и | Й й | К к | Л л | Ԯ ԯ | М м | Н н | Ң ң | О о | П п | Р р | С с | Т т | У у | Ў ў | Х х | Ш ш | Щ щ | Ы ы | Э э | Ю ю | Я я |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IPA | ɑ | ɐ, ə | β | je | jɔ | ɵ | i | j | k | l | ɬ | m | n | ŋ | ɔ | p | r | s | t | u, ə | ʉ | x | ʂ | sʲ | i | e | u, ʉ | jɑ |

Literary language

.svg.png.webp)

The Khanty written language was first created after the October Revolution on the basis of the Latin script in 1930 and then with the Cyrillic alphabet (with the additional letter ⟨ң⟩ for /ŋ/) from 1937.

Khanty literary works are usually written in three Northern dialects, Kazym, Shuryshkar, and Middle Ob. Newspaper reporting and broadcasting are usually done in the Kazymian dialect.

Varieties

Khanty is divided in three main dialect groups, which are to a large degree mutually unintelligible, and therefore best considered three languages: Northern, Southern and Eastern. Individual dialects are named after the rivers they are or were spoken on. Southern Khanty is probably extinct by now.[9][10]

The Salym dialect can be classified as transitional between Eastern and Southern (Honti:1998 suggests closer affinity with Eastern, Abondolo:1998 in the same work with Southern). The Atlym and Nizyam dialects also show some Southern features.

Southern and Northern Khanty share various innovations and can be grouped together as Western Khanty. These include loss of full front rounded vowels: *üü, *öö, *ɔ̈ɔ̈ > *ii, *ee, *ää (but *ɔ̈ɔ̈ > *oo adjacent to *k, *ŋ),[12] loss of vowel harmony, fricativization of *k to /x/ adjacent to back vowels,[9] and the loss of the *ɣ phoneme.[13]

Phonology

A general feature of all Khanty varieties is that while long vowels are not distinguished, a contrast between plain vowels (e.g. /o/) vs. reduced or extra-short vowels (e.g. /ŏ/) is found. This corresponds to an actual length distinction in Khanty's close relative Mansi. According to scholars who posit a common Ob-Ugric ancestry for the two, this was also the original Proto-Ob-Ugric situation.

Palatalization of consonants is phonemic in Khanty, as in most other Uralic languages. Retroflex consonants are also found in most varieties of Khanty.

Khanty word stress is usually on the initial syllable.[14]

Proto-Khanty

| Bilabial | Dental | Palatal(ized) | Retroflex | Velar | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nasal | *m [m] | *n [n] | *ń [nʲ] | *ṇ [ɳ] | *ŋ [ŋ] | |

| Stop/ Affricate |

*p [p] | *t [t] | *ć [tsʲ] | *č̣ [ʈʂ] | *k [k] | |

| Fricative | central | *s [s] | *γ [ɣ] | |||

| lateral | *ᴧ [ɬ] | |||||

| Lateral | *l [l] | *ľ [lʲ] | *ḷ [ɭ] | |||

| Trill | *r [r] | |||||

| Semivowel | *w [w] | *j [j] | ||||

19 consonants are reconstructed for Proto-Khanty, listed with the traditional UPA transcription shown above and an IPA transcription shown below.

A major consonant isogloss among the Khanty varieties is the reflexation of the lateral consonants, *ɬ (from Proto-Uralic *s and *š) and *l (from Proto-Uralic *l and *ð).[13] These generally merge, however with varying results: /l/ in the Obdorsk and Far Eastern dialects, /ɬ/ in the Kazym and Surgut dialects, and /t/ elsewhere. The Vasjugan dialect still retains the distinction word-initially, having instead shifted *ɬ > /j/ in this position. Similarly, the palatalized lateral *ľ developed to /lʲ/ in Far Eastern and Obdorsk, /ɬʲ/ in Kazym and Surgut, and /tʲ/ elsewhere. The retroflex lateral *ḷ remains in Far Eastern, but in /t/-dialects develops into a new plain /l/.

Other dialect isoglosses include the development of original *ć to a palatalized stop /tʲ/ in Eastern and Southern Khanty, but to a palatalized sibilant /sʲ ~ ɕ/ in Northern, and the development of original *č similarly to a sibilant /ʂ/ (= UPA: š) in Northern Khanty, partly also in Southern Khanty.

Far Eastern

The Vakh dialect is divergent. It has rigid vowel harmony and a tripartite (ergative–accusative) case system: The subject of a transitive verb takes the instrumental case suffix -nə-, while the object takes the accusative case suffix. The subject of an intransitive verb, however, is not marked for case and might be said to be absolutive. The transitive verb agrees with the subject, as in nominative–accusative systems.

Vakh has the richest vowel inventory, with five reduced vowels /ĕ ø̆ ə̆ ɑ̆ ŏ/ and full /i y ɯ u e ø o æ ɑ/. Some researchers also report /œ ɔ/.[15][16]

| Bilabial | Dental | Palatal/ized | Retroflex | Velar | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nasal | m | n | nʲ | ɳ | ŋ |

| Plosive | p | t | tʲ | k | |

| Affricate | tʃ | ||||

| Fricative | s | ɣ | |||

| Lateral | l | lʲ | ɭ | ||

| Trill | r | ||||

| Semivowel | w | j |

Surgut

| Bilabial | Dental / Alveolar | Palatal/ized | Post- alveolar | Velar | Uvular | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nasal | m | n̪ | nʲ | ŋ | |||

| Plosive / Affricate | p | t̪ | tʲ ~ tɕ [lower-alpha 1] | tʃ | k [lower-alpha 2] | q [lower-alpha 2] | |

| Fricative | central | s | (ʃ) [lower-alpha 3] | ʁ | |||

| lateral | ɬ [lower-alpha 4] | ɬʲ | |||||

| Approximant | w | l | j | (ʁ̞ʷ) [lower-alpha 5] | |||

| Trill | r | ||||||

- /tʲ/ can be realized as an affricate [tɕ] in the Tremjugan and Agan sub-dialects.

- The velar/uvular contrast is predictable in inherited vocabulary: [q] appears before back vowels, [k] before front and central vowels. However, in loanwords from Russian, [k] may also be found before back vowels.

- The phonemic status of [ʃ] is not clear. It occurs in some words in variation with [s], in others in variation with [tʃ].

- In the Pim sub-dialect, /ɬ/ has recently shifted to /t/, a change that has spread from Southern Khanty.

- The labialized postvelar approximant [ʁ̞ʷ] occurs in the Tremjugan sub-dialect as an allophone of /w/ between back vowels, for some speakers also word-initially before back vowels. Research from the early 20th century also reported two other labialized phonemes: /kʷ~qʷ/ and /ŋʷ/, but these are no longer distinguished.

Northern Khanty

The Kazym dialect distinguishes 18 consonants.

| Bilabial | Dental | Retroflex | Palatal | Velar | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| plain | pal. | ||||||

| Nasal | m | n | nʲ | ɳ | ŋ | ||

| Plosive | p | t | k | ||||

| Fricative | central | s | sʲ | ʂ | x | ||

| lateral | ɬ | ɬʲ | |||||

| Approximant | central | w | j | ||||

| lateral | l | ||||||

| Trill | r | ||||||

The vowel inventory is much simpler. Eight vowels are distinguished in initial syllables: six full /i e a ɒ o u/ and four reduced /ĭ ă ŏ ŭ/. In unstressed syllables, four values are found: /ɑ ə ĕ ĭ/.[18][19]

A similarly simple vowel inventory is found in the Nizyam, Sherkal, and Berjozov dialects, which have full /e a ɒ u/ and reduced /ĭ ɑ̆ ŏ ŭ/. Aside from the full vs. reduced contrast rather than one of length, this is identical to that of the adjacent Sosva dialect of Mansi.[15]

The Obdorsk dialect has retained full close vowels and has a nine-vowel system: full vowels /i e æ ɑ o u/ and reduced vowels /æ̆ ɑ̆ ŏ/).[15] It however has a simpler consonant inventory, having the lateral approximants /l lʲ/ in place of the fricatives /ɬ ɬʲ/ and having fronted *š *ṇ to /s n/.

Grammar

The noun

The nominal suffixes include dual -ŋən, plural -(ə)t, dative -a, locative/instrumental -nə.

For example:[20]

- xot "house" (cf. Finnish koti "home", or Hungarian "ház")

- xotŋəna "to the two houses"

- xotətnə "at the houses" (cf. Hungarian otthon, Finnish kotona "at home", an exceptional form using the old, locative meaning of the essive case ending -na).

Singular, dual, and plural possessive suffixes may be added to singular, dual, and plural nouns, in three persons, for 33 = 27 forms. A few, from məs "cow", are:

- məsem "my cow"

- məsemən "my 2 cows"

- məsew "my cows"

- məstatən "the 2 of our cows"

- məsŋətuw "our 2 cows"

Pronouns

The personal pronouns are, in the nominative case:

| SG | DU | PL | |

| 1st person | ma | min | muŋ |

| 2nd person | naŋ | nən | naŋ |

| 3rd person | tuw | tən | təw |

The cases of ma are accusative manət and dative manəm.

The demonstrative pronouns and adjectives are:

- tamə "this", tomə "that", sit "that yonder": tam xot "this house".

Basic interrogative pronouns are:

- xoy "who?", muy "what?"

Numerals

Khanty numerals, compared with Hungarian and Finnish, are:

| Number | Khanty | Hungarian | Finnish |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | yit, yiy | egy | yksi |

| 2 | katn, kat | kettő, két | kaksi |

| 3 | xutəm | három | kolme |

| 4 | nyatə | négy | neljä |

| 5 | wet | öt | viisi |

| 6 | xut | hat | kuusi |

| 7 | tapət | hét | seitsemän |

| 8 | nəvət | nyolc | kahdeksan |

| 9 | yaryaŋ [A] | kilenc | yhdeksän |

| 10 | yaŋ | tíz | kymmenen |

| 20 | xus | húsz | kaksikymmentä |

| 30 | xutəmyaŋ [B] | harminc | kolmekymmentä |

| 40 | nyatəyaŋ [C] | negyven | neljäkymmentä |

| 100 | sot | száz | sata |

| A Possibly 'short of ten' |

| B 'three tens' |

| C 'four tens' |

The formation of multiples of ten shows Slavic influence in Khanty, whereas Hungarian uses the collective derivative suffix -van (-ven) closely related to the suffix of the adverbial participle which is -va (-ve) today but used to be -ván (-vén). Note also the regularity of [xot]-[haːz] "house" and [sot]-[saːz] "hundred".

Nomen

| Case | Number | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Singular | Dual | Plural | |

| NOM | qɒːt

house |

qɒːtɣən

two houses |

qɒːtət

houses |

| DLAT | qɒːtɐ

to the house |

qɒːtɣənɐ

to the two houses |

qɒːtətɐ

to the houses |

| LOC | qɒːtnə

in the house |

qɒːtɣənnə

in the two houses |

qɒːtətnə

in the houses |

| ABL | qɒːti

from the house |

qɒːtɣəni

from the two houses |

qɒːtəti

from the houses |

| APRX | qɒːtnɐm

towards the house |

qɒːtɣənnɐm

towards the two houses |

qɒːtətnɐm

towards the houses |

| TRSL | qɒːtɣə

as the house |

qɒːtɣənɣə

as the two houses |

qɒːtətɣə

as the houses |

| INSC | qɒːtɐt

with the house |

qɒːtɣənɐt

with the two houses |

qɒːtətɐt

with the houses |

| COM | qɒːtnɐt

with the house |

qɒːtɣənnɐt

with the two houses |

qɒːtətnɐt

with the houses |

| ABE | qɒːtɬəɣ

without the house |

qɒːtɣənɬəɣ

without the two houses |

qɒːtətɬəɣ

without the houses |

Pronouns

| Singular | Dual | Plural | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | 2. | 3. | 1. | 2. | 3. | 1. | 2. | 3. | |

| NOM | mɐː | nʉŋ | ɬʉβ, ɬʉɣ | miːn | niːn | ɬiːn | məŋ | nəŋ, niŋ | ɬəɣ, ɬiɣ |

| ACC | mɐːnt | nʉŋɐt | ɬʉβɐt

ɬʉβət |

miːnt

miːnɐt |

niːnɐt | ɬiːnɐt | məŋɐt | nəŋɐt | ɬəɣɐt |

| DAT | mɐːntem | nʉŋɐti | ɬʉβɐti | miːnɐtem

miːntem minɐti |

niːnɐti | ɬiːnɐti | məŋɐtem

məŋɐti |

nəŋɐti

niŋɐti |

ɬəɣɐti |

| LAT | mɐːntemɐ | nʉŋɐtinɐ

nʉŋɐtenɐ nʉŋɐtijɐ |

ɬʉβɐtiɬɐ

ɬʉβɐtinɐ ɬʉβɐtɐ |

miːnɐtemɐ

miːntemɐ |

niːnɐtinɐ

niːnɐtenɐ niːnɐtijɐ |

ɬiːnɐtiɬɐ

ɬiːnɐtinɐ |

məŋɐtinɐ

məŋɐtemɐ |

nəŋɐtinɐ

nəŋɐtenɐ nəŋɐtijɐ |

ɬəɣɐtiɬɐ

ɬəɣɐtinɐ |

| LOC | mɐːntemnə

mɐːnə, mɐːnnə mɐːn |

nʉŋɐtinə

nʉŋnə nʉŋən, nʉŋn |

ɬʉβɐtiɬnə

ɬʉβɐtinə ɬʉβnə, ɬʉβən |

miːnɐtemnə

miːntemnə miːnnə, miːnən |

niːnɐtinnə

niːnən |

ɬiːnɐtiɬnə

ɬiːnɐtinnə ɬiːnnə, ɬiːnən |

məŋɐtemnə

məŋɐtinnə məŋnə, məŋən |

nəŋɐtinnə

nəŋən, niŋnə |

ɬəɣɐtiɬnə

ɬəɣɐtinnə ɬəɣnə, ɬəɣən |

| ABL | mɐːntemi

mɐːni |

nʉŋɐtini

nʉŋɐteni nʉŋi |

ɬʉβɐtiɬi

ɬʉβɐtini ɬʉβɐti, ɬʉβi |

miːnɐtemi

miːntemi miːnɐti, miːni |

niːnɐtini

niːnɐteni niːni |

ɬiːnɐtiɬi

ɬiːnɐtini ɬiːnɐti, ɬiːni |

məŋtemi

məŋɐtini məŋɐti, məŋi |

nəŋɐtini

nəŋɐteni niŋɐtiji, nəŋi |

ɬəɣɐtiɬi

ɬəɣɐtini ɬəɣɐti, ɬəɣi |

| APRX | mɐːntemnɐm

mɐːnnɐm |

nʉŋɐtəɬnɐm

nʉŋɐtinɐm nʉŋɐtenɐm nʉŋnɐm |

ɬʉβɐtiɬnɐm

ɬʉβɐtinɐm ɬʉβnɐm |

miːnɐtemnɐm

miːnɐtimənɐ miːnɐm |

niːnɐtinɐm

niːnɐtenɐm niːnɐnɐm |

ɬiːnɐtiɬnɐm

ɬiːnɐtinɐm ɬiːnɐtijɐt |

məŋɐtemnɐm

məŋɐtinɐm məŋnɐm |

nəŋɐtinɐm

niŋɐtinɐm nəŋɐtenɐm nəŋɐtijɐ |

ɬəɣɐtiɬnɐm

ɬəɣɐtinɐm ɬəɣnɐm |

| TRSL | mɐːntemɣə

mɐːnɣə |

nʉŋɐtinɣə

nʉŋɐtiɣə nʉŋɐtenɣə nʉŋkə |

ɬʉβɐtiɬɣə

ɬʉβɐtinɣə ɬʉβɐtiɣə ɬʉβkə |

miːnɐtemɣə miːnɐtikkə miːnɣə | niːnɐtinɣə niːnɐtiɣə niːnɐtikkə niːnɣə | ɬiːnɐtiɬɣə ɬiːnɐtinɣə ɬiːnɐtikkə ɬiːnɣə | məŋtemɣə məŋɐtinɣə məŋɐtikkə məŋkə | nəŋɐtinɣə nəŋɐtiɣə nəŋɐtikkə nəŋkə | ɬəɣɐtiɬɣə ɬəɣɐtinɣə ɬəɣɐtikkə ɬəɣkə |

| INSC | mɐːntemɐt | nʉŋɐtinɐt nʉŋɐtenɐt nʉŋɐtijɐt | ɬʉβɐtinɐt ɬʉβɐtiɬɐt ɬʉβɐtijɐt | miːntemɐt | niːnɐtinɐt niːnɐtenɐt niːnɐtijɐt | ɬiːnɐtinɐt ɬiːnɐtiɬɐt ɬiːnɐtijɐt | məŋɐtemɐt məŋɐteβɐt | nəŋɐtinɐt nəŋɐtenɐt nəŋɐtijɐt | ɬəɣɐtinɐt ɬəɣɐtiɬɐt ɬəɣɐtijɐt |

| COM | mɐːntemnɐt mɐːnnɐt | nʉŋɐtinɐt nʉŋɐtenɐt nʉŋnɐt | ɬʉβɐtiɬnɐt ɬʉβɐtəɬnɐt ɬʉβɐtinɐt ɬʉβnɐt | miːnɐtemnɐt miːntemnɐt miːnnɐt | niːnɐtinɐt niːnɐtenɐt niːnnɐt | ɬiːnɐtiɬɐt ɬiːnɐtinɐt ɬiːnnɐt | məŋɐtinɐt məŋɐtemnɐt məŋɐtiβnɐt məŋnɐt | nəŋɐtinɐt nəŋɐtenɐt nəŋnɐt | ɬəɣɐtiɬnɐt ɬəɣɐtinɐt ɬəɣnɐt |

| ABE | mɐːntemɬəɣ | nʉŋɐtiɬəɣ nʉŋɐtinɬəɣ | ɬʉβɐtiɬəɣ | ||||||

Explanation of the case abbreviations

NOM: Nominative case

ACC: Accusative case

DAT: Dative case

LAT: Lative case, collapse of differentiated local cases. Used to indicate the relative location.

LOC: Locative case Used to indicate place and direction.[23]

ABL: Ablative case, external case meaning: moving away from something.[24]

APRX: Aproximative case, used to indicate a path towards.[25]

TRSL: Translative case, used to indicate transformation.[26]

INSC: Instructive case, related to Instrumental case, as in something is an instrument to an action.[27]

COM: Comitatative case, meaning with something.[28]

ABE: Abessive, ised to indicate that something is without x.[29]

| possessee[30] | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| possessor | singular | dual | plural |

| 1sg | -əm | -ɣəɬɐm | -ɬɐm |

| 2sg | -ən, -ɐ, -ɛ | -ɣəɬɐ | -ɬɐ |

| 3sg | -əɬ | -ɣəɬ | -ɬɐɬ |

| 1du | -imen | -ɣəɬəmən | -ɬəmən |

| 2du | -n | -ɣəɬən | -ɬən |

| 3du | -in | -ɣəɬən | -ɬən |

| 1pl | -iβ | -ɣəɬəβ | -ɬəβ |

| 2pl | -in | -ɣəɬən | -ɬən |

| 3pl | -iɬ | -ɣəɬ | -ɬɐɬ |

Morphology

Verbs[31]

Khanty verbs have to agree with the subject in person and number. There are two paradigms for conjugation. One where the verb only agrees with the subject (subjective conjugation column in the verbal suffixes table) and one where the verb agrees with both subject and object (objective conjugation in the same table). In a sentence with a subject and an object the subjective conjugation puts the object in focus. The same kind of sentence with objective conjugation leaves the object topically. [32]

Khanty has the tenses present and past, the moods indicative and imperative and two voices, passive and active. [33] Generally, the present tense is marked and the past is unmarked, but for some verbs present and past are distinguished by vowel alternation or consonant insertion.[34] The order of suffixes is always tense-(passive.)number-person.[35]

Non-finite verb forms are: infinitve, converb, and four particle verb forms.[36] Infinitive can complement a modal verb or a motion verb such as go. Standing alone it means necessity or possibility.[37]

The participles are present, past, negative and conditional. The first two are in use while the latter two are seemingly going extinct.[38]

Questions

Yes/no questions are marked only by intonation. Indirect yes/no questions are constructed with “or” For example:[39] S/he asked if Misha was tired [or not]. Wh-questions most often contain a wh-word in the focus position.[40]

Negation

Negation is marked by the particle əntə, that appears adjecent to the verb and between the particles of particle verbs. [41] This is different from some other uralic languages as those thend to have a negation verb or at least a negation particle that is declined in some way.

Syntax

Both Khanty and Mansi are basically nominative–accusative languages but have innovative morphological ergativity. In an ergative construction, the object is given the same case as the subject of an intransitive verb, and the locative is used for the agent of the transitive verb (as an instrumental) . This may be used with some specific verbs, for example "to give": the literal Anglicisation would be "by me (subject) a fish (object) gave to you (indirect object)" for the equivalent of the sentence "I gave you a fish". However, the ergative is only morphological (marked using a case) and not syntactic, so that, in addition, these may be passivized in a way resembling English. For example, in Mansi, "a dog (agent) bit you (object)" could be reformatted as "you (object) were bitten, by a dog (instrument)".

Khanty is an agglutinative language and employs an SOV order.[42]

Word order

On the phrasal level, the traditional relations are typical for an OV language. For example: PPs can come after the verb. Manner adverbs precede the verb. The verb phrase precedes the auxiliary. The possessor precedes the possessed.[43]

On the sentence level, case alignment in Surgut Khanty clauses follows a nominative-accusative pattern.[44] Both the subject and the object can be dropped if they are pragmatically inferable.[45] This is possible even in the same sentence.

Khanty is a verb final language, but this is not absolute as about 10% of sentences have other phrases behind the verb.[46] While the word order in matrix clauses is more variable, in embedded clauses it is quite strict.[47] The constraints are due to grammatical relations and discourse information. In older sources these phrases have content that was already introduced in the discourse while in newer sources newly introduced content can also be placed post verbally. Schön and Gugán speculate that this is because of contact with other languages, namely Russian.[48]

Imperative

Imperative clauses have the same structure as declarative sentences, apart from complex predicates where the verb may precede the preverb. Prohibitive sentences include a prohibitive particle.[49]

Passive

In Khanty passive voice is achieved by moving other phrases than the subject into subject position, focus on the agent and indefiniteness of the agent.[50]

Pro-drop

In Khanty names or pronouns can only be dropped if they are obvious from the context and marked on the verb.[51]

Lexicon

The lexicon of the Khanty varieties is documented relatively well. The most extensive early source is Toivonen (1948), based on field records by K. F. Karjalainen from 1898 to 1901. An etymological interdialectal dictionary, covering all known material from pre-1940 sources, is Steinitz et al. (1966–1993).

Schiefer (1972)[52] summarizes the etymological sources of Khanty vocabulary, as per Steinitz et al., as follows:

| Inherited | 30% | Uralic | 5% |

| Finno-Ugric | 9% | ||

| Ugric | 3% | ||

| Ob-Ugric | 13% | ||

| Borrowed | 28% | Komi | 7% |

| Samoyedic (Selkup and Nenets) | 3% | ||

| Tatar | 10% | ||

| Russian | 8% | ||

| unknown | 40% |

Futaky (1975)[53] additionally proposes a number of loanwords from the Tungusic languages, mainly Evenki.

Notes

- "Росстат — Всероссийская перепись населения 2020". rosstat.gov.ru. Retrieved 2023-01-03.

- "Итоги Всероссийской переписи населения 2020 года. Таблица 6. Население по родному языку" [Results of the All-Russian population census 2020. Table 6. population according to native language.]. rosstat.gov.ru. Retrieved 2023-01-03.

- Laurie Bauer, 2007, The Linguistics Student's Handbook, Edinburgh

- Abondolo 2017

- "Khanty language, alphabet and pronunciation". omniglot.com. Retrieved 2023-01-04.

- "Росстат — Всероссийская перепись населения 2020". rosstat.gov.ru. Retrieved 2023-01-03.

- Gulya 1966, pp. 5–6.

- Bakró-Nagy, Marianne; Laakso, Johanna; Skribnik, Elena, eds. (2022-03-24). The Oxford Guide to the Uralic Languages. Oxford University PressOxford. doi:10.1093/oso/9780198767664.001.0001. ISBN 978-0-19-876766-4.

- Abondolo 1998, pp. 358–359.

- Honti 1998, pp. 328–329.

- Honti, László (1981), "Ostjakin kielen itämurteiden luokittelu", Congressus Quintus Internationalis Fenno-Ugristarum, Turku 20.-27. VIII. 1980, Turku: Suomen kielen seura, pp. 95–100

- Honti 1998, p. 336.

- Honti 1998, p. 338.

- Estill, Dennis (2004). Diachronic change in Erzya word stress. Helsinki: Finno-Ugrian Society. p. 179. ISBN 952-5150-80-1.

- Abondolo 1998, p. 360.

- Filchenko 2007.

- Csepregi 1998, pp. 12–13.

- Honti 1998, p. 337.

- Kaksin 2007.

- Nikolaeva, I. A. (1999). Ostyak. Lincom Europa.

- Schön, Zsófia; Gugán, Katalin (2022-03-24), "East Khanty", The Oxford Guide to the Uralic Languages, Oxford University PressOxford, pp. 608–635, doi:10.1093/oso/9780198767664.003.0032, ISBN 978-0-19-876766-4, retrieved 2023-08-04

- Schön, Zsófia; Gugán, Katalin (2022-03-24), "East Khanty", The Oxford Guide to the Uralic Languages, Oxford University PressOxford, pp. 608–635, doi:10.1093/oso/9780198767664.003.0032, ISBN 978-0-19-876766-4, retrieved 2023-08-04

- Ostyak, Nikoleva 1999, page 13

- Holmberg & Nikanne, 1993

- Ostyak, Nikoleva 1999, page 13

- Holmberg & Nikanne, 1993

- Holmberg & Nikanne, 1993

- Holmberg & Nikanne, 1993

- Holmberg & Nikanne, 1993

- Schön, Gugán, Zsófia, Katalin (2022). The Oxford guide to the Uralic languages. Oxford University Press. p. 615.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - The Oxford Guide to the Uralic Languages. (2022)

- The Oxford Guide to the Uralic Languages, page 616

- The Oxford Guide to the Uralic Languages, page 616

- The Oxford Guide to the Uralic Languages, page 616

- The Oxford Guide to the Uralic Languages, page 618

- The Oxford Guide to the Uralic Languages, page 618

- The Oxford Guide to the Uralic Languages, page 619

- The Oxford Guide to the Uralic Languages, page 619

- The Oxford Guide to the Uralic Languages, page 625

- The Oxford Guide to the Uralic languages, page 625

- The Oxford Guide to the Uralic languages, page 625

- Grenoble, Lenore A (2003). Language Policy in the Soviet Union. Springer. p. 14. ISBN 9781402012983.

- The Oxford Guide to the Uralic Languages, page 622

- The Oxford guide to Uralic languages, page 622

- The Oxford guide to Uralic languages, page 622

- The Oxford guide to Uralic languages, page 624

- Ostyak (languages of the world), page 57

- The Oxford guide to Uralic languages, page 624

- The Oxford guide to Uralic languages, page 626

- The Oxford guide to Uralic languages, page 622

- The Oxford guide to Uralic languages, page 622

- Schiefer, Erhard (1972). "Wolfgang Steinitz. Dialektologisches und etymologisches Wörterbuch der ostjakischen Sprache. Lieferung 1 – 5, Berlin 1966, 1967, 1968, 1970, 1972". Études Finno-Ougriennes. 9: 161–171.

- Futaky, István (1975). Tungusische Lehnwörter des Ostjakischen. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz Verlag.

References

- Abondolo, Daniel (1998). "Khanty". In Abondolo, Daniel (ed.). The Uralic Languages.

- Csepregi, Márta (1998). Szurguti osztják chrestomathia (PDF). Studia Uralo-Altaica Supplementum. Vol. 6. Szeged. Retrieved 2014-10-11.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Filchenko, Andrey Yury (2007). A grammar of Eastern Khanty (Doctor of Philosophy thesis). Rice University. hdl:1911/20605.

- Gulya, János (1966). Eastern Ostyak chrestomathy. Indiana University Publications, Uralic and Altaic series. Vol. 51.

- Honti, László (1988). "Die Ob-Ugrischen Sprachen". In Sinor, Denis (ed.). The Uralic Languages.

- Honti, László (1998). "ObUgrian". In Abondolo, Daniel (ed.). The Uralic Languages.

- Kaksin, Andrej D. (2007). Казымский диалект хантыйского языка (in Russian). Khanty-Mansijsk: Obsko-Ugorskij Institut Prikladnykh Issledovanij i Razrabotok.

- Steinitz, Wolfgang, ed. (1966–1993). Dialektologisches und etymologisches Wörterbuch der ostjakischen Sprache. Berlin.

{{cite encyclopedia}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Toivonen, Y. H., ed. (1948). K. F. Karjalainen's Ostjakisches Wörterbuch. Helsinki: Suomalais-Ugrilainen Seura.

- Bakró-Nagy, Laakso, Skribnik, ed. (2022). The Oxford Guide to the Uralic Languages. Oxford University Press.

{{cite encyclopedia}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: editors list (link) - Nikolaeva, ed. (1999). Ostyak (Languages of the World). Lincom GmbH.

- Holmberg, A., Nikanne, U., Oraviita, I., Reime, H., & Trosterud, T. (1993). The structure of INFL and the finite clause in Finnish. Case and other functional categories in Finnish syntax, 39, 177

External links

- Khanty Language

- Omniglot

- Documentation of Eastern Khanty

- Khanty basic lexicon at the Global Lexicostatistical Database

- Khanty Language and People

- Khanty–Russian Russian–Khanty dictionary (download), mirror (in case the PDF link gets misdirected)

- Khanty Bibliographical Guide

- OLAC resources in and about the Khanty language

.png.webp)