South Estonian

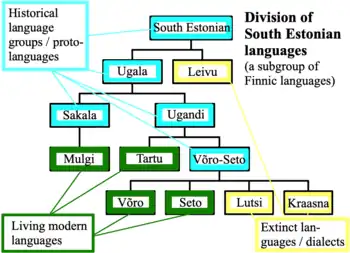

South Estonian is either a Finnic language or an Estonian dialect, spoken in south-eastern Estonia, encompassing the Tartu, Mulgi, Võro and Seto varieties. There is no academic consensus on its status as a dialect or language.[2][3][4][5][6] Diachronically speaking, North and South Estonian are separate branches of the Finnic languages.[3][7]

| South Estonian | |

|---|---|

| Geographic distribution | Baltic States |

Native speakers | 159,900 in Estonia[1] |

| Linguistic classification | Uralic

|

| Subdivisions | |

| Glottolog | sout2679 |

The historical South Estonian (Võro, Seto, Mulgi and Tartu) language area with historical South Estonian language enclaves (Lutsi, Leivu and Kraasna) | |

South Estonian is classified as Definitely Endangered by the UNESCO Atlas of the World's Languages in Danger (2010) | |

Modern Standard Estonian has evolved on the basis of the dialects of Northern Estonia. However, from the 17th to the 19th centuries in Southern Estonia, literature was published in a standardized form of Southern Tartu and Northern Võro. That usage was called Tartu or literary South Estonian.[8] The written standard was used in the schools, churches and courts of the Võro and Tartu linguistic area but not in the Seto and Mulgi areas.

After Estonia gained independence in 1918, the standardized Estonian language policies were implemented further throughout the country. The government officials during the era believed that the Estonian state needed to have one standard language for all of its citizens, which led to the exclusion of South Estonian in education. The ban on the instruction and the use of South Estonian dialects in schools continued during the Soviet occupation (1940–1990).[9]

Since Estonia regained independence in 1991, the Estonian government has become more supportive of the protection and development of South Estonian.[9] A modernized literary form founded on the Võro dialect of South Estonian has been sanctioned.[10][11]

Varieties

The present varieties of the South Estonian language area are Mulgi, Tartu, Võro and Seto. Võro and Seto have remained furthest from the standard written Estonian language and are most difficult for speakers of standard Estonian to understand.[11][12]

Three enclave dialects of South Estonian have been attested. The Leivu and Lutsi enclaves in Latvia became extinct in the 20th century.[12] The Kraasna enclave in Russia, still aware of their identity, have been assimilated linguistically by Russians.[13]

Characteristics

The distinction between South Estonian and North Estonian is starker than any other contrast between Estonian dialects, and is present at every level of the language.[14]

Phonological differences include:[15]

| Trait | South Estonian | North Estonian |

|---|---|---|

| Vowel harmony | present | lost |

| õ in unstressed syllables | present in some dialects | absent |

| Diphthongization of long vowels | ää, õõ retained e.g. pää 'head' |

diphthongized > ea, õe e.g. pea 'head' |

| Raising of long mid vowels | *ee, *öö, *oo raised > i̬i̬, ü̬ü̬, u̬u̬ | ee, öö, oo retained (dialectally diphthongized: ie, üö, uo) |

| Unrounding of ü-diphthongs | no unrounding: äü retained, eü > öü e.g. täüs 'full' |

rounding lost: *äü > äi, *eü > ei e.g. täis 'full' |

| Syncope of *i, *u | present e.g. istma 'to sit' |

absent e.g. istuma 'to sit' |

| Word-initial ts | present in some dialects | absent |

| Assimilations of consonant clusters | *ks > ss, *tk > kk e.g. uss 'door', sõkma 'to knead' |

ks, tk retained e.g. uks 'door', sõtkuma 'to knead' |

| *pc, *kc > *cc > ts e.g. ütsʼ 'one', latsʼ 'child' |

*pc, *kc > ps, ks e.g. üks 'one', laps 'child' | |

| *kn > nn, *kt > tt e.g. nännü(q) 'seen', vatt 'foam' |

*kn > in, *kt > ht e.g. näinud 'seen', vaht 'foam' | |

| Vocalization of syllable-final *k | absent or full vocalization e.g. nagõl 'nail', naar 'laughter', vagi 'wedge' |

*kl > *jl, *kr > *jr, *kj > *jj e.g. nael 'nail', naer 'laughter', vai 'wedge' |

| Treatment of voiced consonant + *h | *nh > hn, *lh > hl, *rh > hr e.g. vahn 'old', kahr 'bear' | *nh > n, *lh > l, *rh > r e.g. vana 'old', karu 'bear' |

| Gemination of single consonants before the adjective ending *-eda/*-edä |

present e.g. kipe 'sore' | absent e.g. kibe 'sore' |

Morphological differences:[16]

| Category | South Estonian | North Estonian |

|---|---|---|

| Nominative plural | -q /ʔ/ | -d |

| Oblique plural | -i- most common | -de- most common |

| Partitive singular | -t | -d |

| Inessive | -h, -n, -hn | -s |

| Illative | -de, -he | -sse |

| Comparative | -mb, -mp, -p | -m |

| da-infinitive | elided in trisyllabic forms e.g. istu 'to sit' |

present in trisyllabic forms e.g. istuda 'to sit' |

| Imperfect | -i- most common | -si- most common |

| Past active participle | -nuq, -nu, -n | -nud, -nd |

| Past passive participle | -tu, -du, -t, -d | -tud, -dud |

| 3rd person singular | endingless (or -s) | -b |

| Negative imperfect | es + connegative | ei + past participle |

History

The two different historical Estonian languages, North and South Estonian, are based on the ancestors of modern Estonians' migration into the territory of Estonia in at least two different waves, both groups speaking differing Finnic vernaculars.[10] Some of the most ancient isoglosses within the Finnic languages separate South Estonian from the entire rest of the family, including a development *čk → tsk, seen in for example *kačku → Standard Estonian katk "plague", Finnish katku "stink", but South Estonian katsk; and a development *kc → tś, seen in for example *ükci "one" → Standard Estonian üks, Finnish yksi, but South Estonian ütś.[7]

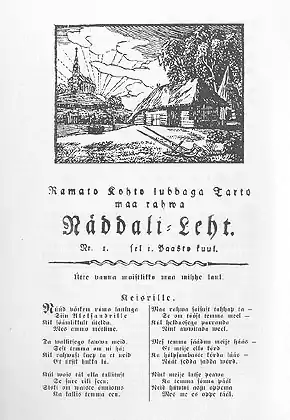

The first South Estonian grammar was written by Johann Gutslaff in 1648 and a translation of the New Testament (Wastne Testament) was published in 1686. In 1806 the first Estonian newspaper Tarto-ma rahwa Näddali leht was published in Tartu literary South Estonian.[12]

Comparison of old literary South Estonian (Tartu), modern literary South Estonian (Võro) and modern standard Estonian:

Lord's Prayer (Meie Esä) in old literary South Estonian (Tartu):

Meie Esä Taiwan: pühendetüs saagu sino nimi. Sino riik tulgu. Sino tahtmine sündigu kui Taiwan, niida ka maa pääl. Meie päiwälikku leibä anna meile täämbä. Nink anna meile andis meie süü, niida kui ka meie andis anname omile süidläisile. Nink ärä saada meid mitte kiusatuse sisse; enge pästä meid ärä kurjast: Sest sino perält om riik, nink wägi, nink awwustus igäwätses ajas. Aamen.

Lord's Prayer (Mi Esä) in modern literary South Estonian (Võro):

Mi Esä taivan: pühendedüs saaguq sino nimi. Sino riik tulguq. Sino tahtminõ sündkuq, ku taivan, nii ka maa pääl. Mi päävälikku leibä annaq meile täämbä. Nink annaq meile andis mi süüq, nii ku ka mi andis anna umilõ süüdläisile. Ni saatku-i meid joht kiusatusõ sisse, a pästäq meid ärq kur’ast, selle et sino perält om riik ja vägi ni avvustus igävädses aos. Aamõn.

Lord's Prayer (Meie isa) in modern standard Estonian:

Meie isa, kes Sa oled taevas: pühitsetud olgu Sinu nimi. Sinu riik tulgu. Sinu tahtmine sündigu, nagu taevas, nõnda ka maa peal. Meie igapäevast leiba anna meile tänapäev. Ja anna meile andeks meie võlad, nagu meiegi andeks anname oma võlglastele. Ja ära saada meid kiusatusse, vaid päästa meid ära kurjast. Sest Sinu päralt on riik ja vägi ja au igavesti. Aamen.

The South Estonian literary language declined after the 1880s as the northern literary language became the standard for Estonian.[17] Under the influence of the European liberal-oriented nationalist movement it was felt that there should be a unified Estonian language. The beginning of the 20th century saw a period for the rapid development of the northern-based variety.

Present situation

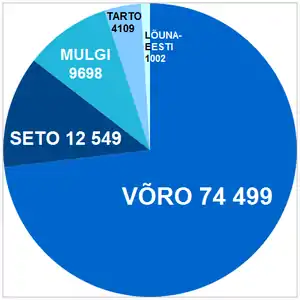

The South Estonian language began to undergo a revival in the late 1980s. Today, South Estonian is used in the works of some of Estonia's most well-known playwrights, poets, and authors. Most success has been achieved in promoting the Võro language and a new literary standard based on Võro. Mulgi and especially Tartu dialects, however, have very few speakers left. The 2011 census in Estonia counted 101,857 self-reported speakers of South Estonian: 87,048 speakers of Võro (including 12,549 Seto speakers), 9,698 Mulgi speakers, 4,109 Tartu language speakers and 1,002 other South Estonian speakers who didn't specify their regional language/dialect.[18]

The 2021 census in Estonia counted 159,900 self-reported speakers of South Estonian: 125,780 speakers of Võro (including 26,220 Seto speakers), 14,380 Mulgi speakers and 19,740 Tartu language speakers.[19]

Language sample of modern literary (Võro) South Estonian:

Article 1 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights:

Kõik inemiseq sünnüseq vapos ja ütesugumaidsis uma avvo ja õiguisi poolõst. Näile om annõt mudsu ja süämetunnistus ja nä piät ütstõõsõga vele muudu läbi käümä.

All human beings are born free and equal in dignity and rights. They are endowed with reason and conscience and should act towards one another in a spirit of brotherhood.

See also

References

- "Rahva ja eluruumide loendus 2021 – eesti keelt kõnelev rahvastik murdekeele oskuse, vanuserühma, soo ja elukoha (haldusüksus) järgi, 31. detsember 2021" [Population and housing census 2021 - Estonian-speaking population by dialect proficiency, age group, gender and place of residence (administrative unit), December 31, 2021] (in Estonian).

- Grünthal, Riho; Anneli Sarhimaa (2004). Itämerensuomalaiset kielet ja niiden päämurteet. Helsinki: Finno-Ugrian Society.

- Sammallahti, Pekka (1977), "Suomalaisten esihistorian kysymyksiä" (PDF), Virittäjä: 119–136

- Laakso, Johanna (2014), "The Finnic Languages", in Dahl, Östen; Koptjevskaja-Tamm, Maria (eds.), The Circum-Baltic Languages: Typology and Contact, Amsterdam: John Benjamins Publishing Company

- Pajusalu, Karl (2009). "The reforming of the Southern Finnic language area" (PDF). Mémoires de la Société Finno-Ougrienne. 258: 95–107. ISSN 0355-0230. Retrieved 2015-10-17.

- Salminen, Tapani (2003), Uralic Languages, retrieved 2015-10-17

- Kallio, Petri (2007). "Kantasuomen konsonanttihistoriaa" (PDF). Mémoires de la Société Finno-Ougrienne (in Finnish). 253: 229–250. ISSN 0355-0230. Retrieved 2009-05-28. Note that reconstructed *č and *c stand for affricates [t͡ʃ], [t͡s].

- South Estonian literary language @google scholar

- Sutton, Margaret (2004). Civil Society Or Shadow State?. IAP. pp. 116, 117. ISBN 978-1-59311-201-1.

- Rannut, Mart (2004). "Language Policy in Estonia" (PDF). Noves SL. Revista de Sociolingüística. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2010-07-03. Retrieved 2009-02-27.

- estonica. "Language, Dialects and layers". Archived from the original on September 27, 2007. Retrieved 2009-02-27.

- Abondolo, Daniel Mario (1998). "Literary Estonian". The Uralic Languages. Taylor & Francis. p. 116. ISBN 978-0-415-08198-6.

- Olson, James; Lee Brigance Pappas (1994). An Ethnohistorical Dictionary of the Russian and Soviet Empires. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 216. ISBN 0-313-27497-5.

- Kask 1984, p. 6.

- Kask 1984, pp. 6–7.

- Kask 1984, pp. 7–8.

- Kaplan, Robert (2007). Language Planning and Policy in Europe. Multilingual Matters. p. 50. ISBN 978-1-84769-028-9.

- Rahva ja eluruumide loendus 2011 – emakeel ja eesti emakeelega rahvastiku murdeoskus

- Rahva ja eluruumide loendus 2021 – eesti keelt kõnelev rahvastik murdekeele oskuse, vanuserühma, soo ja elukoha (haldusüksus) järgi, 31. detsember 2021

Bibliography

- Eller, Kalle (1999): Võro-Seto language. Võro Instituut'. Võro.

- Iva, Sulev; Pajusalu, Karl (2004): The Võro Language: Historical Development and Present Situation. In: Language Policy and Sociolinguistics I: "Regional Languages in the New Europe" International Scientific Conference; Rēzeknes Augstskola, Latvija; 20–23 May 2004. Rezekne: Rezekne Augstskolas Izdevnieceba, 2004, 58 – 63.

- Kask, Arnold (1984): Eesti murded ja kirjakeel. Emäkeele seltsi toimetised 16.

.png.webp)