Scottish Gaelic phonology and orthography

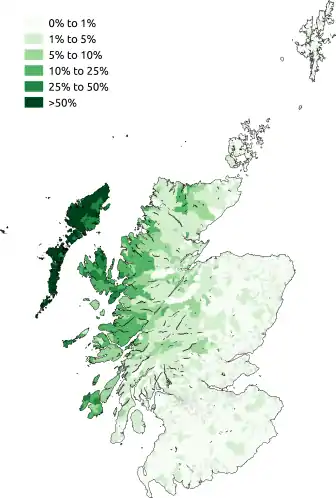

There is no standard variety of Scottish Gaelic; although statements below are about all or most dialects, the north-western dialects (Outer Hebrides, Skye and the Northwest Highlands) are discussed more than others as they represent the majority of speakers.

Gaelic phonology is characterised by:

- a phoneme inventory particularly rich in sonorant coronal phonemes (commonly nine in total)

- a contrasting set of palatalised and non-palatalised consonants

- strong initial word-stress and vowel reduction in unstressed syllables

- The presence of preaspiration of stops in certain contexts

- falling intonation in most types of sentences, including questions

- lenition and extreme sandhi phenomena

Due to the geographic concentration of Gaelic speakers along the western seaboard with its numerous islands, Gaelic dialectologists tend to ascribe each island its own dialect. On the mainland, no clear dialect boundaries have been established to date but the main areas are generally assumed to be Argyllshire, Perthshire, Moidart/Ardnamurchan, Wester Ross and Sutherland.

History of the discipline

Descriptions of the language have largely focused on the phonology. Welsh naturalist Edward Lhuyd published the earliest major work on Scottish Gaelic after collecting data in the Scottish Highlands between 1699 and 1700, in particular data on Argyll Gaelic and the now obsolete dialects of north-east Inverness-shire.[1]

Following a significant gap, the middle to the end of the twentieth century saw a great flurry of dialect studies in particular by Scandinavian scholars, again focussing largely on phonology:

- 1938 Nils Holmer Studies on Argyllshire Gaelic published by the University of Uppsala

- 1937 Carl Borgstrøm The Dialect of Barra published by Norsk Tidsskrift for Sprogvidenskap

- 1940 Carl Borgstrøm The Dialects of the Outer Hebrides published by Norsk Tidsskrift for Sprogvidenskap

- 1941 Carl Borgstrøm The Dialects of Skye and Ross-shire published by the Norwegian University Press

- 1956 Magne Oftedal The Gaelic of Leurbost, Isle of Lewis published by Norsk Tidsskrift for Sprogvidenskap

- 1957 Nils Holmer The Gaelic of Kintyre published by the Dublin Institute for Advanced Studies

- 1962 Nils Holmer The Gaelic of Arran published by the Dublin Institute for Advanced Studies

- 1966 Gordon MacGillFhinnein Gàidhlig Uibhist a Deas ("South Uist Gaelic") published by the Dublin Institute for Advanced Studies

- 1973 Elmar Ternes The Phonemic Analysis of Scottish Gaelic (focussing on Applecross Gaelic) published by the Helmut Buske Verlag

- 1978 Nancy Dorian East Sutherland Gaelic published by the Dublin Institute for Advanced Studies

- 1989 Máirtín Ó Murchú East Perthshire Gaelic published by the Dublin Institute for Advanced Studies

In the period between 1950 and 1963, fieldwork was carried out to document all then remaining Gaelic dialects, culminating in the publication of the five-volume Survey of the Gaelic Dialects of Scotland by the Dublin Institute for Advanced Studies in 1997. The survey collected data from informants as far south as Arran, Cowal, Brig o' Turk, east to Blairgowrie, Braemar and Grantown-on-Spey, north-east to Dunbeath and Portskerra and all areas west of these areas, including St Kilda.

Vowels

The following is a chart of the monophthong vowel phonemes appearing in Scottish Gaelic:[2]

| Front | Central | Back | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| unrounded | rounded | |||

| Close | i | ɯ | u | |

| Near-close | ɪ | |||

| Close-mid | e | ə | ɤ | o |

| Open-mid | ɛ | ɔ | ||

| Open | a | |||

All vowel phonemes except for /ɪ/ and /ə/ can be both long (represented with ⟨ː⟩) and short. Phonologically, /a/ behaves both as a front or back vowel depending on the geographical area and vowel length.

Diphthongs

The number of diphthongs in Scottish Gaelic depends to some extent on the dialect in question but most commonly, 9 or 10 are described: /ei, ɤi, ai, ui, iə, uə, ɛu, ɔu, au, ia/.[4]

Orthography

Vowels are written as follows:

A table of vowels with pronunciations in the IPA Spelling Pronunciation Scottish English [SSE] equivalents As in a, á [a], [a] cat bata, ás à, a [aː] father/calm bàta, barr e [ɛ], [e] get le, teth è, é [ɛː], [eː] wary, late/lady gnè, dé i [i], [iː] tin, sweet sin, ith ì, i [iː] evil, machine mìn, binn o [ɔ], [o] top poca, bog ò, o, ó [ɔː], [oː] jaw, boat/go pòcaid, corr, mór u [u] brute Tur ù, u [uː] brewed tùr, cum

The English equivalents given are approximate, and refer most closely to the Scottish pronunciation of Standard English. The vowel [aː] in English father is back [ɑː] in Southern English. The ⟨a⟩ in English late in Scottish English is the pure vowel [eː] rather than the more general diphthong [eɪ]. The same is true for the ⟨o⟩ in English boat, [oː] in Scottish English, instead of the diphthong [əʊ].

Digraphs and trigraphs

The language uses many vowel combinations, which can be categorised into two types, depending on the status of one or more of the written vowels in the combinations.

Category 1: vowel plus glide vowels. In this category, vowels in digraphs/trigraphs that are next to a neighbouring consonant are for all intents and purposes part of the consonant, showing the broad or slender status of the consonant.

Spelling Pronunciation Preceding consonant Following consonant As in ai [a]~[ɛ]; (unstressed syllables) [ɛ]~[ə]~[i] preceded by a broad consonant or Ø followed by a slender consonant (stressed syllable) caileag, ainm [ɛnɛm];

(unstressed syllables) iuchair, geamair, dùthaichài [aː] preceded by a broad consonant or Ø followed by a slender consonant àite, bara-làimhe ea [ʲa]~[e]~[ɛ] [in part dialect variation] preceded by a slender consonant or Ø followed by a broad consonant geal; deas; bean eà [ʲaː] preceded by a slender consonant or Ø followed by a broad consonant ceàrr èa [ɛː] preceded by a slender consonant or Ø followed by a broad m, mh or p nèamh èa [ia] preceded by a slender consonant or Ø followed by a broad consonant other than m, mh or p dèan ei [e]~[ɛ] preceded by a slender consonant or Ø followed by a slender consonant eile; ainmeil èi [ɛː] preceded by a slender consonant or Ø followed by a slender consonant sèimh éi [eː] preceded by a slender consonant or Ø followed by a slender consonant fhéin eo [ʲɔ] preceded by a slender consonant or Ø followed by a broad consonant deoch eò [ʲɔː] preceded by a slender consonant or Ø followed by a broad consonant ceòl eòi [ʲɔː] preceded by a slender consonant or Ø followed by a slender consonant feòil eu [eː]~[ia] [dialect variation, broadly speaking south versus north] preceded by a slender consonant or Ø followed by a broad consonant ceum; feur io [i], [(j)ũ(ː)] preceded by a slender consonant or Ø followed by a broad consonant fios, fionn ìo [iː], [iə] preceded by a slender consonant or Ø followed by a broad consonant sgrìobh, mìos iu [(j)u] preceded by a slender consonant or Ø followed by a broad consonant piuthar, fliuch iù [(j)uː] preceded by a slender consonant or Ø followed by a broad consonant diùlt iùi [(j)uː] preceded by a slender consonant or Ø followed by a slender consonant diùid oi [ɔ], [ɤ] preceded by a broad consonant or Ø followed by a slender consonant boireannach, goirid òi [ɔː] preceded by a broad consonant or Ø followed by a slender consonant òinseach ói [oː] preceded by a broad consonant or Ø followed by a slender consonant cóig ui [u], [ɯi], [uːi]; (unstressed syllables) [ə/ɨ] preceded by a broad consonant or Ø followed by a slender consonant muir, uighean, tuinn ùi [uː] preceded by a broad consonant or Ø followed by a slender consonant dùin

Category 2: 'diphthongs' and 'triphthongs'. In this category, vowels are written together to represent either a diphthong, or what was in Middle Irish a diphthong.

Spelling Pronunciation Preceding consonant Following consonant As in ao [ɯː] preceded by a broad consonant or Ø followed by a broad consonant caol ia [iə], [ia] preceded by a slender consonant or Ø followed by a broad consonant biadh, dian ua [uə] preceded by a broad consonant or Ø followed by a broad consonant ruadh, uabhasach

Category 2 digraphs can by followed by Category 1 glides, and thereby form trigraphs:

Spelling Pronunciation Preceding consonant Following consonant As in aoi [ɯː]~[ɤ] preceded by a broad consonant or Ø followed by a slender consonant caoil; gaoithe iai [iə], [ia] preceded by a slender consonant or Ø followed by a slender consonant Iain uai [uə] preceded by a broad consonant or Ø followed by a slender consonant ruaidh, duais

Consonants

Like the closely related languages Modern Irish and Manx, Scottish Gaelic contains what are traditionally referred to as "broad" and "slender" consonants. Historically, Primitive Irish consonants preceding the front vowels /e/ and /i/ developed a [j]-like coarticulation similar to the palatalized consonants found in Russian[5][6] while the consonants preceding the non-front vowels /a/, /o/ and /u/ developed a velar coarticulation. While Irish distinguishes "broad" (i.e. phonetically velar or velarised consonants) and "slender" (i.e. phonetically palatal or palatalised consonants), in Scottish Gaelic velarisation is only present for /n̪ˠ l̪ˠ rˠ/. This means that consonants marked "broad" by the orthography are, for the most part simply unmarked, while "slender" consonants are palatal or palatalised. The main exception to this are the labials (/p pʰ m f v/), which have lost their palatalised forms. The only trace of their original palatalisation is a glide found before a back vowel, e.g. beum /peːm/ ('stroke') vs beò /pjɔː/ ('alive'). Celtic linguists traditionally transcribe slender consonants with an apostrophe (or more accurately, a prime) following the consonant (e.g. m′) and leave broad consonants unmarked.

The unaspirated stops in some dialects (east and south) are voiced (see below), as in Manx and Irish. In the Gaelic of Sutherland and the MacKay Country, this is the case, while in all other areas full voicing is allophonic with regional variation, voicing occurs in certain environments, such as within breath groups and following homorganic nasals (see below). The variation suggests that the unaspirated stops at the underlying phonological level are voiced, with devoicing an allophonic variant that in some dialects has become the most common realisation. East Perthshire Gaelic reportedly lacks either a voicing or an aspiration distinction and has merged these stops. Irish dialects and Manx also have devoiced unaspirated consonants in certain environments.

Consonants of Scottish Gaelic Labial Coronal Dorsal Glottal Dental Alveolar Palatal Velar Plosive pʰ p t̪ʰ t̪ tʲʰ tʲ kʲʰ kʲ kʰ k Fricative f v s̪ ʃ ç ʝ x ɣ h Nasal m n̪ˠ n ɲ Approximant l̪ˠ l ʎ j Rhotic Tap ɾ ɾʲ Trill rˠ

In the modern languages, there is sometimes a stronger contrast from Old Gaelic in the assumed meaning of "broad" and "slender". In the modern languages, the phonetic difference between "broad" and "slender" consonants can be more complex than mere "velarisation"/"palatalisation". For instance, the Gaelic "slender s" is so palatalised that it has become postalveolar [ʃ].

Certain consonants (in particular the fricatives [h x ç ɣ ʝ v] and the lenis coronals [l n ɾ ɾʲ]) are rare in initial position except as a result of lenition.

Phonetic variation

Gaelic phonemes may have various allophones as well as dialectal or variations in pronunciation not shown in the chart above. The more common ones are:

Velarised l

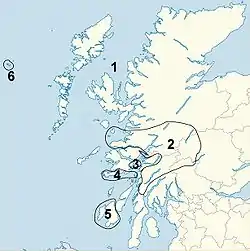

Velarised /l̪ˠ/ has 6 main realisations as shown on the map:[7]

- Area 1, by far the most populous, has [l̪ˠ]. The area includes most of the Outer Hebrides, the Highlands and areas south of central western areas such as Kintyre, Arran, Argyll and East Perthshire.

- Area 2, Ardnamurchan, Moidart, Lochaber, South Lorn, Eigg and Upper Badenoch has [l̪ˠw] or [wl̪ˠ]. This feature is strongly associated with Eigg to the point it is referred to as "glug Eigeach", the Eigg gulp.

- Area 3, between Mull and Lismore has vocalised it: [w]

- Area 4, in the south of Mull and Easdale, has [ð] or [ðˠ]

- Area 5, Islay, has [t̪ˠ] or [t̪ˠl̪ˠ]

- Area 6, St Kilda, had [w] or [ʊ̯]

The Survey of Scottish Gaelic Dialects occasionally reports labialised forms such as [l̪ˠw] or [l̪ˠv] outside the area they predominantly appear in, for example in Harris and Wester Ross.

Aspiration

The fortis stops /pʰ, t̪ʰ, tʲʰ, kʲʰ, kʰ/ are voiceless and aspirated; this aspiration occurs as postaspiration in initial position and, in most dialects, as preaspiration in medial position after stressed vowels.[9] Similar to the manifestation of aspiration, the slender consonants have a palatal offglide when initial and a palatal onglide when medial or final.[10]

Preaspiration

Preaspiration varies in strength and can manifest as glottal ([ʰ] or [h]) or can vary depending on the place of articulation of the preaspirated consonant; being [ç] before "slender" segments and [x] before "broad" ones.[11] The occurrence of preaspiration follows a hierarchy of c > t > p; i.e. if a dialect has preaspiration with /pʰ/, it will also have it in the other places of articulation. Preaspiration manifests itself as follows:[7]

- Area 1 as [xk xt xp] and [çkʲ çtʲ çp]

- Area 2 as [xk xt hp] and [çkʲ çtʲ hp]

- Area 3 as [xk ht hp] and [çkʲ htʲ hp]

- Area 4 as [ʰk ʰt ʰp]

- Area 5 as [xk] and [çkʲ] (no preaspiration of t and p)

- Area 6 no preaspiration

Lack of preaspiration coincides with full voicing of the unaspirated stops. Area 6 dialects in effect largely retain the Middle Irish stops, as has Manx and Irish.

Nasalisation

In some Gaelic dialects (particularly the north-west), stops at the beginning of a stressed syllable become voiced when they follow nasal consonants of the definite article, for example: taigh ('a house') is [t̪ʰɤj] but an taigh ('the house') is [ən̪ˠ d̪⁽ʱ⁾ɤj]; cf. also tombaca ('tobacco') [t̪ʰomˈbaʰkə]. In such dialects, the lenis stops /p, t, tʲ, kʲ, k/ tend to be completely nasalised, thus doras ('a door') is [t̪ɔrəs], but an doras ('the door') is [ə n̪ˠɔrəs].[12] This is similar to eclipsis in Classical Gaelic and Irish, but not identical as it only occurs when a nasal is phonetically present whereas eclipsis in Classical Gaelic and Irish may occur in positions following a historic (but no longer present) nasal.[13]

The voicing of voiceless aspirated stops and the nasalisation of the unaspirated (voiced) stops occurs after the preposition an/am ('in'), an/am ('their'), the interrogative particle an and a few other such particles and occasionally, after any word ending in a nasal e.g. a bheil thu a' faighinn cus? as [ɡʱus] rather than [kʰus].

In southern Hebridean dialects, the nasal optionally drops out entirely before a consonant, including plosives.[14]

Lenition and spelling

The lenited consonants have special pronunciations.

Lenition changes[15] Radical Lenited Broad Slender Orthography Broad Slender [p] [pj][16] b bh [v] [vj][16] [kʰ] [kʲʰ] c ch [x] [ç] [t̪] [tʲ] d dh [ɣ] [ʝ] [f] [fj][16] f fh silent [k] [kʲ] g gh [ɣ] [ʝ] [l̪ˠ] [ʎ] l† [l̪ˠ] [l̪] [m] [mj][16] m mh [v] [vj] [n̪ˠ] [ɲ] n† [n] [pʰ] [pʰj][16] p ph [f] [fj][16] [rˠ] r† [ɾ] [s̪] [ʃ] s sh [h] [hj][16] [t̪ʰ] [tʲʰ] t th [h] [hj][16]

- ^† Lenition of initial l n r is not shown in writing. Word initially, these are always assumed to have the strong values (/(l̪ˠ) ʎ n̪ˠ ɲ rˠ/) unless they are in a leniting environment or unless they belong to a small and clearly defined group of particle (mostly the forms of the prepositions ri and le). Elsewhere, any of the realisations of l n r may occur; [l̪ˠ] is lenitable only in Harris Gaelic which retains the fourth l-sound [l̪].

The /s̪/ is not lenited when it appears before /m p t̪ k/. Lenition may be blocked when homorganic consonants (i.e. those made at the same place of articulation) clash with grammatical lenition rules. Some of these rules are active (particularly with dentals), others have become fossilised (i.e. velars and labials). For example, blocked lenition in the surname Caimbeul ('Campbell') (vs Camshron 'Cameron') is an incident of fossilised blocked lenition; blocked lenition in air an taigh salach "on the dirty house" (vs air a' bhalach mhath 'on the good boy') is an example of the productive lenition blocking rule.

Stress

Stress is usually on the first syllable: for example drochaid ('a bridge') [ˈt̪rɔxɪtʲ]. Words where stress falls on another syllable are generally indicated by hyphens: these include certain adverbs such as an-diugh ('today') [əɲˈdʲu] and an-còmhnaidh ('always') [əŋˈgɔ̃ːnɪ]. In loanwords, a long vowel outside the first syllable is also indicative of stress shift, for example buntàta ('potato') [bən̪ˠˈt̪aːht̪ə]. Stress shift may also occur in close compound nouns or nouns with prefixes, though the stress patterns here are less predictable, for instance in beul-aithris ('oral literature') can be both [ˈpial̪ˠaɾʲɪʃ] or [pjal̪ˠˈaɾʲɪʃ].

Epenthesis

A distinctive characteristic of Gaelic pronunciation (also present in Scots and Scottish English dialects (cf. girl [ɡɪɾəl] and film [fɪləm]) is the insertion of epenthetic vowels between certain adjacent consonants. This affects orthographic l n r when followed by orthographic b bh ch g gh m mh; and orthographic m followed by l r s ch.

- tarbh ('bull') — [t̪ʰaɾav]

- Alba ('Scotland') — [al̪ˠapə].

Occasionally, there are irregular occurrences of the epenthetic vowel, for example in Glaschu /kl̪ˠas̪əxu/ ('Glasgow').

There are often wide variations in vowel quality in epenthetic vowels, as illustrated by a map showing the pronunciations of "dearbh."[8]

- Area 1 [tʲɛɾav]

- Area 2 [tʲaɾa(v)] with the [v] appearing in the northwestern region but not the southeastern

- Area 3 [tʲɛɾɛv]

- Area 4 [tʲɛɾʊ] with vocalization of the [v]

- Area 5 [tʲɛɾəv] with reduction of the epenthetic vowel as in Irish

Elision

Schwa [ə] at the end of a word is dropped when followed by a word beginning with a vowel. For example:

- duine ('a man') — [ˈt̪ɯɲə]

- an duine agad ('your man') — [ən̪ˠ ˈt̪ɯɲ akət̪]

Tones

Of all the Celtic languages, lexical tones only exist in the dialects of Lewis[17] and Sutherland[18] in the extreme north of the Gaelic-speaking area. Phonetically and historically, these resemble the tones of Norway, Sweden and southwestern Denmark; these languages have tonal contours typical for monosyllabic words and those for disyllabic words. In Lewis Gaelic, it is difficult to find minimal pairs. Among the rare examples are: bodh(a) [po.ə] ('underwater rock') vs. bò [poː] ('cow'), and fitheach [fi.əx] ('raven') vs. fiach [fiəx] ('debt'). Another example is the tonal difference between ainm [ɛnɛm] and anam [anam], the latter of which has the tonal contour appropriate to a disyllable. These tonal differences are not to be found in Ireland or elsewhere in the Scottish Gàidhealtachd.[19] Furthermore, they are disappearing entirely among younger speakers even in Lewis.[20]

Morphophonology

adh.svg.png.webp)

Morphophonological variation

The regular verbal noun suffix, written <(e)adh>, has several pronunciations.

- Area 1: [əɣ] (as expected from the spelling)

- Area 2: [ək]

- Area 3: [əv]

- Area 4: no suffix

- Area 5: [ʊ]

- Area 6 is characterized by a high level of variation both between words and adjacent informants

For some words it is possible to resolve the indeterminate area, for example with the verb sgrìobadh ("scraping"):

- Area 1: [əɣ] (as expected from the spelling)

- Area 2: [ək]

- Area 3: [əv]

- Area 4: no suffix

- Area 5: [ʊ]

- Area 6: [ə]

Notes

- Campbell 1963, p. ?.

- MacAulay 1992, p. 236.

- Bauer 2011.

- MacAulay 1992, p. 237.

- Thurneysen 1993, p. ?.

- Thurneysen 1980, p. ?.

- Ó Dochartaigh 1997.

- Ó Dochartaigh 1997, vol. 3.

- Silverman 2003, pp. 578–579.

- Silverman (2003:579), citing Borgstrøm (1940)

- Silverman 2003, p. 579.

- Bauer 2011, p. 311.

- Bauer 2011, p. 312.

- MacGillFhinnein 1966, p. 24.

- Based on Gillies (1993)

- Labial consonants /m p b f v/ do not make a phonemic contrast between broad and slender, though before or after back vowels, historic slender consonants have become clusters of a labial consonant and [j]. In initial position, the [j] follows the consonant and in medial position it precedes it. The same vocalic environment also causes /hj/ as a result of lenited /tʲʰ/ and [ʃ]

- Ternes 1980, p. ?.

- Dorian 1978, pp. 60–1.

- Clement 1994, p. 108.

- Nance 2015, p. 569.

References

- Michael, Bauer (2011) [2010], Blas na Gàidhlig: The Practical Guide to Scottish Gaelic Pronunciation, Akerbeltz, ISBN 978-1-907165-00-9

- Borgstrøm, Carl H.J. (1940), The dialects of the Outer Hebrides, A linguistic survey of the dialects of Scotland, vol. 1, Oslo, Norway: Norwegian Universities Press

- Campbell, J. L.; Thomson, Derick (1963), Edward Lhuyd in the Scottish Highlands, 1699-1700, Oxford University Press

- Clement, R.D. (1994), "Word tones and svarabhakti", in Thomson, Derick S. (ed.), Linguistic Survey of Scotland, University of Edinburgh

- MacAulay, Donald (1992), The Celtic Languages, Cambridge University Press

- MacGillFhinnein, Gordon (1966), Gàidhlig Uibhist a Deas [South Uist Gaelic] (in Scottish Gaelic), Dublin Institute for Advanced Studies

- Ó Dochartaigh, Cathair (1997), Survey of the Gaelic Dialects of Scotland I-V, Dublin Institute for Advanced Studies, ISBN 978-1-85500-165-7

- Nance, Claire (2015), "'New' Scottish Gaelic speakers in Glasgow: A phonetic study of language revitalisation.", Language in Society, 44 (4): 553–579, doi:10.1017/S0047404515000408, S2CID 146161228

- Silverman, Daniel (2003), "On the rarity of pre-aspirated stops", Journal of Linguistics, 39 (3): 575–598, CiteSeerX 10.1.1.529.8048, doi:10.1017/S002222670300210X, S2CID 53698769

- Thurneysen, Rudolf (1993) [1946], A Grammar of Old Irish, translated by Binchy, D. A.; Bergin, Osborn, Dublin: Dublin Institute for Advanced Studies, ISBN 978-1-85500-161-9

Further reading

- Ó Maolalaigh, Roibeard; MacAonghuis, Iain (1997), Scottish Gaelic in Three Months, Hugo's Language Books, ISBN 978-0-85285-234-7

External links

- A detailed pronunciation guide on Akerbeltz (IPA)

- Multimedia maps of dialectal differences in phonology based on the Scottish Gaelic Dialect Survey.