The Erotic

The Erotic, as defined and discussed by educator and poet, Audre Lorde, is a profound resource of feminine power housed within the spiritual plane of women's existence. This power, as she describes in her 1978 essay "Uses of the Erotic: The Erotic as Power", is a sense of deep satisfaction – beyond the sexual deceptively portrayed in the pornographic – elevated by a profound feeling that lives in the joy and fulfillment of a woman's being. This fulfillment becomes, as Lorde describes, the conscious decision in a woman's work,[1] the power that embodies and manifests change in the fight against the oppression of women, especially Black women and women of color. This power of the erotic is a lifestyle, a potentiality that has been recognized as a threat, treated as suspect, and therefore suppressed out of fear. Lorde writes, "women so empowered are dangerous".[1] Lorde demonstrates in redefining and reclaiming the erotic – a profound feeling of knowing, an empowering knowledge, "a lens through which we scrutinize all aspects of our existence"[1] – that the erotic is a critical element in dismantling the social and political hierarchy situated in a white patriarchal power structure that reproduces the erotic as pornographic.

Lorde writes that "The erotic has often been misnamed by men and used against women…[confused] with its opposite, the pornographic…[and] pornography emphasizes sensation without feeling".[1] For the erotic to simply be the pornographic, would require the woman's experience to be reduced into a spiritual "world of flattened affect"[1] thus rejecting the derivative of the very word erotic altogether, which "comes from the Greek word eros, the personification of love in all its aspects"[1] [emphasis added]. To speak of the erotic as Lorde does, is to "speak of the lifeforce of women; of that creative energy empowered, the knowledge and use of which [women] are now reclaiming in our language, our history, our dancing, our loving, our work, our lives…[and exemplify] how acutely and fully we can feel in doing"[1]

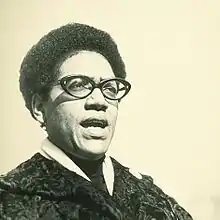

Audre Lorde

Audre Lorde (1934–1992) is best known for her work as an, "American poet, essayist, and autobiographer known for her passionate writings on lesbian feminism and racial issues"[2] Her powerful writing included over a dozen publications in the form of poetry and essays, winning multiple national and international awards for her writing, and was one of the primary founders of Kitchen Table: Women of Color Press.[3] She has also been hailed as, " The Black feminist, lesbian, poet, mother, and warrior."[4] Other famous poems and essays written by Lorde include:[4]

- A Burst Of Light

- The Black Unicorn

- Between Ourselves

- Cables To Rage

- The Cancer Journals

- The First Cities

- From A Land Where Other People Live

- I Am Your Sister: Black Women Organizing Across Sexualities

- Lesbian Party: An Anthology

- Need: A Chorale For Black Women Voices

- The New York Head Shop And Museum

- Our Dead Behind Us: Poems

- Sister Outsider: Essays And Speeches

- The Marvelous Arithmetics Of Distance: Poems

- Undersong: Chosen Poems Old And New

- Uses Of The Erotic: The Erotic As Power

- Woman Poet—The East

- Zami: A New Spelling of My Name

Beyond pornography

As Lorde writes, "the erotic has often been misnamed by men and used against women…made into the confused, the trivial, the psychotic, the plasticized sensation"[1] Buried under this destructive social guise, the erotic gets confused with the pornographic, resulting in an interchangeable use within Western societies. Lorde challenges this misuse and labors to dismantle its foundation by explaining the two are not interchangeable, but are in fact, opposite one another. Lorde writes "Pornography is a direct denial of the power of the erotic, for it represents the suppression of true feeling"[1] Whereas what the erotic more appropriately represents, is a power in knowing and feeling, "those physical, emotional, and psychic expressions of what is deepest and strongest and richest within each of us…the passions of love, in its deepest meanings…the self-connection shared…the measure of joy"[1] The erotic is, as Lorde eloquently writes, "the nurturer, or nursemaid of all our deepest knowledge"[1] The erotic is the spiritual powerhouse within the woman, the driving force housed within the manifestation of joy, true sensation, a profound sense of feeling, not simply a forced impression of feeling as the pornographic moves to sway understanding. This misrepresentation and misnaming in Western culture "gives rise to [the] distortion which results in pornography and obscenity" resulting in the absolute "abuse of feeling".[1] According to Young (2012), the term "Erotic" discussed by Audre Lorde has often been misrepresented and used as a tool to over-sexualize and under value women in a patriarchal society. While this term is often synonymous with pornography, it was meant to provide liberation for women, a freedom that can be found from self reflection and human connection with other woman. The primary mechanism of oppression, is found in the misuse and understanding of systemic power structures that continue to oppress women in their voice and expression of self.[5]

Further discussion

American legal scholar, Catharine MacKinnon, builds upon Lorde's concepts that underscore the pornographic as a form of oppression by emphasizing that pornography not only works to oppress the erotic power of women, but also suppresses women's freedom of speech in her piece "Pornography, Civil Rights, and Speech". Pornography eroticizes "the unspeakable abuse: the rape, the battery, the sexual harassment, the prostitution, and the sexual abuse of children. Only in the pornography it is called something else: sex, sex, sex, sex, and sex, respectively" which thus contributes to the perpetuation of inequality between men and women, promoting a sense of normalization for these atrocities of abuse[6] The erotic power that Lorde describes, a resource that "lies in a deeply female and spiritual plane"[1] becomes twisted, perverted and used against women to maintain female subordination in the pornographic. In her work, MacKinnon draws connections between pornographic depictions of sexual acts and documented cases of sexual assault in which the abusive actions of the male perpetrator demonstrate a direct correlation between the pornographic depictions of sexuality and sexual acts of aggression. In this same work, she quotes a study detailing cases of men who watched pornography depicting acts of sexual assault confessed self-reported to being more inclined of committing aggressive acts of behavior towards women to include the greater likelihood of engaging in acts of sexual assault. These images create a desensitization regarding this particular type of aggressive behavior constructing a reality that silences women and the violence committed against women's bodies. When women report instances of sexual assault or violent sexual behavior, their voices are dismissed, as pornography has distorted the reality of sexual aggression. Pornography becomes another way of silencing women, another way of distorting their experiences. Pornography becomes the snatching away of credibility, sexual violence replaced with a westernized version of 'eroticism'.[6]

See also

References

- Lorde, Audre. "Uses of the Erotic: The Erotic as Power" (PDF). uk.sagepub. Retrieved 12 Feb 2019.

- "Audre Lorde | Biography, Books, & Facts". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 2020-09-23.

- Lorde, Audre. "The Uses of the Erotic: The Erotic as Power" (PDF). Sage UK.

- "About Audre Lorde". The Audre Lorde Project. 2007-11-06. Retrieved 2020-10-21.

- Young, Nikki (2013). ""Uses of the Erotic" for Teaching Queer Studies". WSQ: Women's Studies Quarterly. 40 (3–4): 301–305. doi:10.1353/wsq.2013.0023. ISSN 1934-1520. S2CID 85125779.

- MacKinnon, Catharine (2018). "Pornography, Civil Rights, and Speech". Readings in Moral Philosophy: 268–278.