The Great Gatsby (1974 film)

The Great Gatsby is a 1974 American romantic drama film based on the 1925 novel of the same name by F. Scott Fitzgerald. The film was directed by Jack Clayton, produced by David Merrick, and written by Francis Ford Coppola. It stars Robert Redford in the title role of Jay Gatsby, along with Mia Farrow, Sam Waterston, Bruce Dern, and Karen Black.

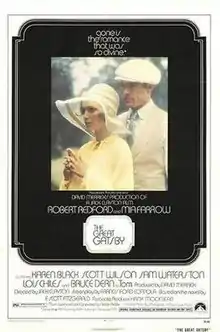

| The Great Gatsby | |

|---|---|

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Jack Clayton |

| Screenplay by | Francis Ford Coppola |

| Based on | The Great Gatsby by F. Scott Fitzgerald |

| Produced by | David Merrick |

| Starring | |

| Cinematography | Douglas Slocombe |

| Edited by | Tom Priestley |

| Music by | Nelson Riddle |

Production company | Newdon Productions |

| Distributed by | Paramount Pictures |

Release date |

|

Running time | 146 minutes[1] |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $7 million |

| Box office | $26.5 million[2] |

The Great Gatsby was preceded by 1926 and 1949 films of the same name. Despite a mixed reception by critics, the 1974 film grossed over $26 million against a $7 million budget. Coppola later stated that the film failed to follow his screenplay. In 2013, a fourth film adaptation was produced.

Plot

Writer Nick Carraway pilots his boat across the harbor to his cousin Daisy and her husband Tom’s mansion in East Egg. While there, he learns Tom and Daisy's marriage is troubled and Tom is having an affair with a woman in New York. Nick lives in a small cottage in West Egg, next to a mysterious tycoon named Gatsby, a former Oxford student and decorated World War I veteran, who regularly throws extravagant parties at his home.

Tom takes Nick to meet his mistress, Myrtle, who is married to George Wilson, an automotive mechanic. George needs to purchase a vehicle from Tom, but Tom is only there to draw Myrtle to his city apartment, where he hits her in the face when she taunts him with Daisy's name.

Back on Long Island, Daisy wants to set Nick up with her friend, Jordan, a professional golfer. When Nick and Jordan attend a party at Gatsby's home, Nick is invited for a private meeting with Gatsby, who asks him to lunch the following day.

At lunch, Nick meets Gatsby's business partner, a Jewish gangster and gambler named Meyer Wolfsheim, who rigged the 1919 World Series. The following day, Jordan appears at Nick's work and requests he invite Daisy to his house so that Gatsby can meet with her. Gatsby surprises Daisy at lunch, and it is revealed that Gatsby and Daisy were once lovers, though she would not marry him because he was poor.

Daisy and Gatsby have an affair, which soon becomes obvious. While Tom and Daisy entertain Gatsby, Jordan, and Nick at their home, Daisy, on a hot summer day, proposes they go into the city as a diversion. At the Plaza Hotel, Gatsby and Daisy reveal their affair and Gatsby wants Daisy to admit she never loved Tom. She is unable to and drives off in Gatsby's car.

During the drive home, Daisy hits Myrtle when Myrtle runs into the street. Believing that it was Gatsby who killed Myrtle, since Tom tells or implies this to him, George later goes to Gatsby's mansion and fatally shoots him as he relaxes in the swimming pool, then commits suicide.

Nick holds a funeral for Gatsby where he meets Gatsby's father and learns Gatsby's original name is "Gatz". No one else attends the funeral. Afterward, Daisy and Tom continue with their lives as though nothing occurred. Nick breaks up with Jordan and moves back west, frustrated with eastern ways, and lamenting Gatsby's inability to escape his past.

Cast

- Robert Redford as Jay Gatsby

- Mia Farrow as Daisy Buchanan

- Bruce Dern as Tom Buchanan

- Sam Waterston as Nick Carraway

- Karen Black as Myrtle Wilson, George's wife

- Scott Wilson as George Wilson, Myrtle's husband

- Lois Chiles as Jordan Baker

- Edward Herrmann as Ewing Klipspringer

- Howard Da Silva as Meyer Wolfsheim

- Kathryn Leigh Scott as Catherine Wilson, Myrtle's sister

- Regina Baff as Miss Baedecker

- Vincent Schiavelli as Thin Man

- Roberts Blossom as Mr. Gatz

- Beth Porter as Mrs. McKee

- Patsy Kensit as Pammy Buchanan

Production

Development

Robert Evans planned on making The Great Gatsby with his wife Ali MacGraw as Daisy as it was her favorite book. Truman Capote was hired to write a script that turned out to be unusable despite Capote's $300,000 fee.[3] Evans made a deal with Broadway producer David Merrick as producer of the movie, and it was Merrick who bought the rights for between $350,000 and $500,000 from F. Scott Fitzgerald's daughter.[4]

Casting

Evans originally sought Warren Beatty for the role of Jay Gatsby, but Beatty turned him down, reluctant to act opposite MacGraw. With Beatty out, Evans offered the role to Jack Nicholson, but Nicholson also reportedly was wary of acting with MacGraw and was unable to make a financial deal.[5][6]

Evans then sought 49-year-old Marlon Brando for the role coveted by 38-year-old Robert Redford, who broke through to superstardom in 1973, the year The Great Gatsby remake was lensed.[7] Although Brando was too old for the part, he had reestablished himself as a box office star with the twin successes of The Godfather and Last Tango in Paris. Incensed at his loss of income when he surrendered his profit participation points for $100,000 to Paramount before the release of The Godfather, Brando personally negotiated his deal, demanding an unprecedented salary reportedly as high as $4 million salary, frankly revealing that the high salary would recoup his losses from the sale of his points. Gulf + Western CEO Charles Bludhorn, whose conglomerate owned Paramount, vetoed any such deal on the grounds that the two movies were separate entities. Brando refused to be in Godfather II when his salary demands were not met.

Robert Redford, who had bid on the rights to the novel himself but lost out to Merrick was hired after Paramount failed to land the three sought-after stars, but filling the role of Daisy Buchanan proved difficult. MacGraw subsequently lost the part after she left Evans for Steve McQueen. MacGraw and McQueen approached producer Merrick through their agents and offered themselves as a package, but McQueen was turned down on the grounds that Redford already was cast. Without McQueen as her co-star, she dropped the project, although Evans claimed it was he himself who terminated her participation in the movie.

Candace Bergen and Katharine Ross reportedly were offered the role. Mia Farrow sent a cable to Evans asking him to consider her for the role, and director Jack Clayton liked the idea of casting her. Faye Dunaway wanted the role so badly she offered to do a screen test, but Clayton was not interested in her.

Screenplay

Truman Capote was the original screenwriter but he was replaced by Francis Ford Coppola. Coppola had just finished directing The Godfather, but was unsure of its commercial reception and he needed the money. He believes he got the job on the recommendation of Robert Redford, who had liked a rewrite Coppola did on The Way We Were. Coppola "had read Gatsby but wasn't familiar with it." He checked himself into a hotel room in Paris (Oscar Wilde's old room) and started. He later recalled:

I was shocked to find that there was almost no dialogue between Daisy and Gatsby in the book, and was terrified that I'd have to make it all up. So I did a quick review of Fitzgerald's short stories and, as many of them were similar in that they were about a poor boy and a rich girl, I helped myself to much of the authentic Fitzgerald dialogue from them. I decided that perhaps an interesting idea would be to do one of those scenes that lovers typically have, where they finally get to be together after much longing, and have a "talk all night" scene, which I'd never seen in a film. So I did that – I think a six-page scene in which Daisy and Gatsby stay up all night and talk. And I remember my wife telling me that she and the kids were in New York when The Godfather opened, and it was a big hit and there were lines around the block at five theaters in the city, which was unheard of at the time. I said, "Yeah, yeah, but I've got to finish the Gatsby script." And I sent the script in, just in time. It had taken me two or three weeks to complete.[8]

On his commentary track for the DVD release of The Godfather, Coppola refers to writing the Gatsby script, adding "Not that the director paid any attention to it. The script that I wrote did not get made."

William Goldman, who loved the novel, said in 2000 that he actively campaigned for the job of adapting the script, but was astonished by the quality of Coppola's work:

I still believe it to be one of the great adaptations... I called him [Coppola] and told him what a wonderful thing he had done. If you see the movie, you will find all this hard to believe... The director who was hired, Jack Clayton, is a Brit... he had one thing all of them have in their blood: a murderous sense of class... Well, Clayton decided this: that Gatsby's parties were shabby and tacky, given by a man of no elevation and taste. There went the ball game. As shot, they were foul and stupid and the people who attended them were foul and silly, and Robert Redford and Mia Farrow, who would have been so perfect as Gatsby and Daisy, were left hung out to dry. Because Gatsby was a tasteless fool and why should we care about their love? It was not as if Coppola's glory had been jettisoned entirely, though it was tampered with plenty; it was more that the reality and passions it depicted were gone.[9]

Filming

The Rosecliff and Marble House mansions in Newport, Rhode Island and an exterior of Linden Place mansion in Bristol, Rhode Island, were used for Gatsby's house while scenes at the Buchanans' home were filmed at Pinewood Studios in Buckinghamshire, England. One driving scene was shot in Windsor Great Park, UK. Other scenes were filmed in New York City and Uxbridge, Massachusetts.

Reception

The film received mixed reviews, being praised for its faithful interpretation of the novel but also criticized for lacking any true emotion or feelings towards the Jazz Age. Based on 37 total reviews collected by Rotten Tomatoes, the film has an overall approval rating of 41%, with an average rating of 5/10. The critical consensus reads: "The Great Gatsby proves that even a pair of tremendously talented leads aren't always enough to guarantee a successful adaptation of classic literary source material."[10] Despite this, the film was a financial success, making $26,533,200[2] against a $7 million budget.[2]

Tennessee Williams, in his book Memoirs (p. 78), wrote: "It seems to me that quite a few of my stories, as well as my one acts, would provide interesting and profitable material for the contemporary cinema, if committed to...such cinematic masters of direction as Jack Clayton, who made of The Great Gatsby a film that even surpassed, I think, the novel by Scott Fitzgerald."[11][12]

Vincent Canby's 1974 review in The New York Times typifies the critical ambivalence: "The sets and costumes and most of the performances are exceptionally good, but the movie itself is as lifeless as a body that's been too long at the bottom of a swimming pool," Canby wrote at the time. "As Fitzgerald wrote it, The Great Gatsby is a good deal more than an ill-fated love story about the cruelties of the idle rich...The movie can't see this through all its giant closeups of pretty knees and dancing feet. It's frivolous without being much fun."[13]

Stanley Kauffmann of The New Republic wrote: "In sum this picture is a total failure of every requisite sensibility. A long, slow, sickening bore."[14]

Variety's review was likewise split: "Paramount's third pass at The Great Gatsby is by far the most concerted attempt to probe the peculiar ethos of the Beautiful People of the 1920s. The fascinating physical beauty of the $6 million-plus film complements the utter shallowness of most principal characters from the F. Scott Fitzgerald novel. Robert Redford is excellent in the title role, the mysterious gentleman of humble origins and bootlegging connections...The Francis Ford Coppola script and Jack Clayton's direction paint a savagely genteel portrait of an upper class generation that deserved in spades what it received circa 1929 and after."[15]

Roger Ebert gave the movie two and a half stars out of four. Comparing film to the book details, Ebert stated: "The sound track contains narration by Nick that is based pretty closely on his narration in the novel. But we don't feel. We've been distanced by the movie's overproduction. Even the actors seem somewhat cowed by the occasion; an exception is Bruce Dern, who just goes ahead and gives us a convincing Tom Buchanan."[16]

The author's daughter, Frances "Scottie" Fitzgerald, who sold the film rights, had reread her father's novel and noted how Mia Farrow on-set looked the part as her father's Daisy, while Robert Redford also asked advice to match the author's intent, but her father, she noted, was more in the narrator, Nick.[17] However, after viewing the film, Fitzgerald's daughter criticized Farrow's performance as Daisy.[18] Although she praised Farrow as a "fine actress," Scottie noted that Farrow seemed unable to convey the "intensely Southern nature" of Daisy's character.[18]

Awards and honors

The film won two Academy Awards, for Best Costume Design (Theoni V. Aldredge) and Best Music (Nelson Riddle). It also won three BAFTA Awards for Best Art Direction (John Box), Best Cinematography (Douglas Slocombe), and Best Costume Design (Theoni V. Aldredge). (The male costumes were executed by Ralph Lauren, the female costumes by Barbara Matera.) It won a Golden Globe Award for Best Supporting Actress (Karen Black) and received three further nominations for Best Supporting Actor (Bruce Dern and Sam Waterston) and Most Promising Newcomer (Sam Waterston).

The film was nominated by the American Film Institute for inclusion in the 2002 list of films, AFI's 100 Years...100 Passions.[19]

| Award | Category | Recipient/Nominee | Result |

|---|---|---|---|

| Academy Awards | Best Costume Design | Theoni V. Aldredge | Won |

| Best Original Score | Nelson Riddle | Won | |

| British Academy Film Awards | Best Cinematography | Douglas Slocombe | Won |

| Best Costume Design | Theoni V. Aldredge | Won | |

| Best Production Design | John Box | Won |

Charts

The soundtrack was released by Paramount Records (L45481)

| Chart (1974) | Position |

|---|---|

| Australia (Kent Music Report)[20] | 22 |

See also

References

- "The Great Gatsby (A)". British Board of Film Classification. March 12, 1974. Retrieved April 7, 2013.

- The Great Gatsby, Box Office Information. Archived April 13, 2012, at the Wayback Machine The Numbers. Retrieved May 22, 2012.

- Evans, Robert (1994). The Kid Stays in the Picture. New York: Hachette Books. pp. 247–259. ISBN 0786860596.

- Bryer, Jackson R.; et al., eds. (2000). F. Scott Fitzgerald: New Perspectives. Athens, GA: University of Georgia Press. p. 112.

- Schoell, William; Quirk, Lawrence J. (2006). The Sundance Kid: A Biography of Robert Redford. Lanham, MD: Taylor Trade Publishing. p. 110.

- McGilligan, Patrick (November 9, 2015). Jack's Life: A Biography of Jack Nicholson (Updated and Expanded). ISBN 9780393350975.

- "The Great Gatsby". smithsonian.com. Smithsonian Institution. Retrieved July 17, 2023.

- Coppola, Francis Ford (April 16, 2013). "Gatsby and Me". Town & Country. Hearst. 167 (5394): 40. ISSN 0040-9952. Archived from the original on February 2, 2017. Retrieved January 21, 2017.

- Goldman, William (2000). Which Lie Did I Tell?. London: Bloomsbury. pp. 95–96. ISBN 978-0-375-40349-1. OCLC 183338523. OL 24755200M. Wikidata Q60387665.

- The Great Gatsby at Rotten Tomatoes

- Williams, Tennessee (1975). Memoirs. Doubleday & Co.

- Sinyard, Neil (2000). Jack Clayton. UK: Manchester University Press. p. 289. ISBN 0-7190-5505-9.

- Canby, Vincent (1974). "A Lavish Gatsby Loses Book's Spirit". The New York Times, March 28, 1974

- "TNR Film Classics: 'The Great Gatsby' (April 13, 1974)". The New Republic. Archived from the original on May 5, 2019. Retrieved September 3, 2019.

- Variety staff, (1973). "Review: The Great Gatsby". Variety, December 31, 1973

- Ebert, Roger. "The Great Gatsby Movie Review Archived July 23, 2013, at the Wayback Machine". Chicago Sun-Times. rogerebert.com. January 1, 1974

- "Mia's Back and Gatsby's Got Her". people.com. March 4, 1974. Archived from the original on August 31, 2018. Retrieved September 1, 2018.

- Tredell, Nicolas (February 28, 2007). Fitzgerald's The Great Gatsby: A Reader's Guide. London: Continuum Publishing. p. 101. ISBN 978-0-8264-9010-0. Retrieved June 6, 2022 – via Internet Archive.

- "AFI's 100 Years...100 Passions Nominees" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on May 17, 2017. Retrieved August 19, 2016.

- Kent, David (1993). Australian Chart Book 1970–1992 (illustrated ed.). St Ives, N.S.W.: Australian Chart Book. p. 281. ISBN 0-646-11917-6.