Great Rift Valley

The Great Rift Valley (Bonde la ufa, in Swahili) is a series of contiguous geographic trenches, approximately 7,000 kilometres (4,300 mi) in total length, that runs from Lebanon in Asia to Mozambique in Southeast Africa.[1] While the name continues in some usages, it is rarely used in geology as it is considered an imprecise merging of separate though related rift and fault systems.

This valley extends northward for 5,950 km through the eastern part of Africa, through the Red Sea, and into Western Asia. Several deep, elongated lakes, called ribbon lakes, exist on the floor of this rift valley: Lake Malawi and Lake Tanganyika are examples of such lakes. The region has a unique ecosystem and contains a number of Africa's wildlife parks.

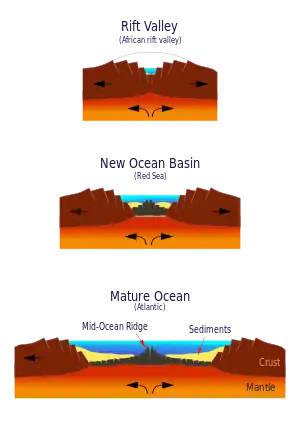

The term Great Rift Valley is most often used to refer to the valley of the East African Rift, the divergent plate boundary which extends from the Afar Triple Junction southward through eastern Africa, and is in the process of splitting the African Plate into two new and separate plates. Geologists generally refer to these evolving plates as the Nubian Plate and the Somali Plate.

Theoretical extent

Today these rifts and faults are seen as distinct, although connected, but originally, the Great Rift Valley was thought to be a single feature that extended from Lebanon in the north to Mozambique in the south, where it constitutes one of two distinct physiographic provinces of the East African mountains. It included what today is called the Lebanese section of the Dead Sea Transform, the Jordan Rift Valley, Red Sea Rift and the East African Rift.[2] These rifts and faults were formed 35 million years ago.

Asia

The northernmost part of the Rift corresponds to the central section of what is called today the Dead Sea Transform (DST) or Rift. This midsection of the DST forms the Beqaa Valley in Lebanon, separating the Mount Lebanon range from the Anti-Lebanon Mountains. Further south it is known as the Hula Valley separating the Galilee mountains and the Golan Heights.[3]

The Jordan River begins here and flows southward through Lake Hula into the Sea of Galilee in Israel. The Rift then continues south through the Jordan Rift Valley into the Dead Sea on the Israeli-Jordanian border. From the Dead Sea southwards, the Rift is occupied by the Wadi Arabah, then the Gulf of Aqaba, and then the Red Sea.[3]

Off the southern tip of Sinai in the Red Sea, the Dead Sea Transform meets the Red Sea Rift which runs the length of the Red Sea. The Red Sea Rift comes ashore to meet the East African Rift and the Aden Ridge in the Afar Depression of East Africa. The junction of these three rifts is called the Afar Triple Junction.[3]

Africa

The East African Rift follows the Red Sea to the end before turning inland into the Ethiopian highlands, dividing the country into two large and adjacent but separate mountainous regions. In Kenya, Uganda, and the fringes of South Sudan, the Great Rift runs along two separate branches that are joined to each other only at their southern end, in Southern Tanzania along its border with Zambia. The two branches are called the Western Rift Valley and the Eastern Rift Valley.

The Western Rift, also called the Albertine Rift, is bordered by some of the highest mountains in Africa, including the Virunga Mountains, Mitumba Mountains, and Ruwenzori Range. It contains the Rift Valley lakes, which include some of the deepest lakes in the world (up to 1,470 metres (4,820 ft) deep at Lake Tanganyika).

Much of this area lies within the boundaries of national parks such as Virunga National Park in the Democratic Republic of Congo, Rwenzori National Park and Queen Elizabeth National Park in Uganda, and Volcanoes National Park in Rwanda. Lake Victoria is considered to be part of the rift valley system although it actually lies between the two branches. All of the African Great Lakes were formed as the result of the rift, and most lie in territories within the rift.

In Kenya, the valley is deepest to the north of Nairobi. As the lakes in the Eastern Rift have no outlet to the sea and tend to be shallow, they have a high mineral content as the evaporation of water leaves the salts behind. For example, Lake Magadi has high concentrations of soda (sodium carbonate) and Lake Elmenteita, Lake Bogoria, and Lake Nakuru are all strongly alkaline, while the freshwater springs supplying Lake Naivasha are essential to support its current biological variety.

The southern section of the Rift Valley includes Lake Malawi, the third-deepest freshwater body in the world, which reaches 706 metres (2,316 ft) in depth and separates the Nyassa plateau of Northern Mozambique from Malawi. The rift extends southwards from Lake Malawi as the valley of the Shire River, which flows from the lake into the Zambezi River. The rift continues south of the Zambezi as the Urema Valley of central Mozambique.[4]

See also

References

- Merriam-Webster, Inc 편집부 (1997). MERRIAM WEBSTER'S GEOGRAPHICAL DICTIONARY 3/E(H). Merriam-Webster. p. 444. ISBN 978-0-87779-546-9.

- Philip Briggs; Brian Blatt (15 July 2009). Ethiopia: the Bradt travel guide. Bradt Travel Guides. p. 450. ISBN 978-1-84162-284-2.

- G. Yirgu; C. J. (Cindy J.) Ebinger; P. K. H. Maguire (2006). The Afar Volcanic Province Within the East African Rift System: Special Publication No 259. Geological Society. pp. 306–307. ISBN 978-1-86239-196-3.

- Steinbruch, Franziska (2010). Geology and geomorphology of the Urema Graben with emphasis on the evolution of Lake Urema, Journal of African Earth Sciences, Volume 58, Issue 2, 2010, Pages 272-284. ISSN 1464-343X, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jafrearsci.2010.03.007.

Further reading

- Africa's Great Rift Valley, 2001, ISBN 978-0-8109-0602-0

- Tribes of the Great Rift Valley, 2007, ISBN 978-0-8109-9411-9

- East African Rift Valley lakes, 2006, OCLC 76876862

- Photographic atlas of the Mid-Atlantic Ridge Rift Valley, 1977, ISBN 978-0-387-90247-0

- Rift Valley fever : an emerging human and animal problem, 1982, ISBN 978-92-4-170063-4

- Rift valley: definition and geologic significance, Giacomo Corti (National Research Council of Italy, Institute of Geosciences and Earth Resources) – The Ethiopian Rift Valley, 2013,

- Big crack is evidence that East Africa could be splitting in two, by Lucia Perez Diaz, CNN. Updated April 5, 2018

.svg.png.webp)