Montclair Art Museum

The Montclair Art Museum (MAM) is located in Montclair, New Jersey and holds a collection of over 12,000 objects showcasing American and Native North American art. Through its public programs, art classes, and exhibitions, MAM strives to create experiences that inspire, challenge, and foster community to shape our shared future.

.jpg.webp) | |

| Established | Chartered 1909; opened 1914 |

|---|---|

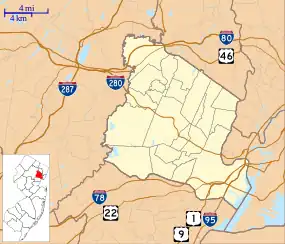

| Location | Montclair, New Jersey, U.S. |

| Type | Art museum[1] |

| Collections | Native American, American, Contemporary |

| Director | Ira Wagner |

| Public transit access | NJ Transit (bus and rail), Walnut Street Station; DeCamp Bus Lines |

| Website | www |

Montclair Art Museum | |

| |

| Location | 3 S. Mountain Avenue, Montclair, New Jersey |

| Coordinates | 40°49′7″N 74°13′27″W |

| Built | 1913 |

Since it opened in 1914 as the first museum in New Jersey that granted access to the public and the first dedicated solely to art, it has been privately funded.

Collection

The Montclair Art Museum (MAM) is one of the few museums in the United States devoted to American art and Native American art forms. The collection consists of more than 12,000 works. The American collection comprises paintings, prints, drawings, photographs, and sculpture dating from the 18th century to the present. The museum's holdings of traditional and contemporary American Indian art and artifacts represent the cultural achievements in weaving, pottery, wood carving, jewelry, and textiles of indigenous Americans from seven major regions—Northwest Coast, California, Southwest, Plains, Woodlands, Southeast, and the Arctic; the work of contemporary American Indian artists is also represented.

The museum has the only gallery in the world dedicated solely to the work of the 19th-century American painter George Inness, who lived in Montclair from 1885 to 1894 and painted in the area. MAM's Inness paintings are, according to one critic, "the crown of the Montclair Art Museum's collection".[2] The intimate George Inness Gallery displays selected works from the museum's 21 Inness paintings, two of his watercolors, and an etching by the artist.[3] It also features the work of sculptor William Couper, who lived in Montclair for fifteen years while sculpting and for another thirty in retirement.

Artists represented in the collection include Tony Abeyta, Josef Albers, Milton Avery, Will Barnet, Romare Bearden, Thomas Hart Benton, Carl Borg, Margaret Bourke-White, Alexander Calder, Ching Ho Cheng, Thomas Cole, Willie Cole, Stuart Davis, Willem de Kooning, Richard Diebenkorn, Elsie Driggs, Asher B. Durand, Thomas Eakins, Lee Friedlander, Arshile Gorky, Marsden Hartley, Robert Henri, Winslow Homer, Edward Hopper, George Inness, Ben Jones, Donald Judd, Michael Lenson, Helen Levitt, Roy Lichtenstein, Robert Longo, Whitfield Lovell, Man Ray, Thomas Manley, Knox Martin, Ma-Pe-Wi, Robert Motherwell, Dan Namingha, Alice Neel, Louise Nevelson, Tom Nussbaum, Georgia O'Keeffe, Sarah Miriam Peale, Rembrandt Peale, Charles Willson Peale, Philip Pearlstein, Maurice Prendergast, Oscar Bluemner, Ad Reinhardt, Mark Rothko, Morgan Russell, John Singer Sargent, George Segal, Ben Shahn, Lorna Simpson, Jaune Quick-To-See Smith, Joseph Stella, Kay WalkingStick, Andy Warhol, Max Weber, and James Abbott McNeill Whistler.

History

The arrival of the railroad in Montclair in the 1830s transformed a rural agricultural village into a prosperous suburban community, with a rail link to New York that was too expensive for the working class that traveled by street cars and trolleys.[4] Montclair's arts community centered on landscape painter George Inness, who visited for several seasons beginning in 1878 and made it his home from 1885 until he died in 1894,[5] when the New York Times described Montclair as "the home of more prominent artists and wealthy art connoisseurs, probably, than any other place in New-Jersey."[6] Others had preceded him as early as the 1860s, when illustrators Harry Fenn and Charles Parsons commuted by rail to their New York City studios, just as Inness and others did in the decades that followed.[5] They were year-round resident-commuters and varied in their stylistic approaches, unlike the impressionists that abandoned city life to gather for the summer in the "art colonies" at the end of the 19th century in Cos Cob and Old Lyme, Connecticut, and New Hope, Pennsylvania.[7] Charles Eaton painted in a style much like that of Inness[7] and Frederick Judd Waugh devoted himself to seascapes,[8] while painter Henry Rankin Poore preferred a "workaday realism " in subject and texture of brushwork and his colleague Frederick Ballard Williams adopted a "more rough-hewn and turbulent form".[5] Walter and Emilie Greenough worked as stained-glass designers in the studio of John LaFarge, who lived in Montclair for a time as well.[7] Sculptors included Jonathan Scott Hartley, Inness's son-in-law, and William Couper.[7][lower-alpha 1]

The town created a Village Improvement Society in 1878, superseded by a Municipal Art Commission in 1908, to beautify Montclair and preserve the charm of a country town.[9] The Commission's head was William T. Evans, an Irish immigrant dry-goods magnate who had acquired the Inness estate in 1900.[10] Between the early 1880s and 1913, Evans amassed a collection of more than 800 American paintings, by far the largest collection of American art before World War I. In 1907, he donated several dozen works to the Smithsonian American Art Museum in Washington, D.C. (named "National Gallery of Art" at that time),[11] and grew that number to 160 by the time of his death in 1918.[12] In 1909, Evans offered to donate 26 oil paintings to the town of Montclair on condition that it provide a fireproof gallery space to house and display them.[13]: 25 The proposal was defeated in a referendum in 1910.[13]: 28

In response to that rejection, on December 8, 1910, the Municipal Art Commission transformed itself into the Montclair Art Association and proposed to create and manage an art gallery without government support. Raising funds still proved difficult until another Montclair resident, Florence Rand Lang (1861–1943), agreed to bear most of the expense and her gift of $50,000, much of it for the purchase of the site, transformed the project from a gallery into a museum.[14][lower-alpha 2] She had arrived in Montclair from Massachusetts as a teenager in 1873. Her initial donation was the first of many that totaled more than $250,000 over the next thirty years, plus $200,000 in her will and more from her estate.[16][lower-alpha 3] She was heir to much of the Rand family fortune, amassed by her father Jasper Rand (1837–1909) and bachelor uncle Addison C. Rand (1841–1900), who together had founded Rand Drill Company in 1871.[18][19][lower-alpha 4]

Needing a dedicated structure to house the collections, museum trustee Michel Le Brun hired Albert R. Ross to design a neoclassical building. Ross had worked on several Carnegie libraries and the Pueblo County Courthouse (1908–12) in Colorado.[lower-alpha 5]

When the museum opened on January 15, 1914, it was the first museum in New Jersey that granted access to the public and the first dedicated solely to art.[27] On the circular lawn in front of the museum's entrance, the founders placed a bronze sculpture by Hermon Atkins MacNeil, The Sun Vow, another gift from Evans. It remains there as a signature piece for the museum, blending Native American and American themes.[lower-alpha 6] At its opening the museum had two collections gifted by its principal organizer, Evans, and its principal funder, Lang. Evans' donation of American art included 2 sculptures and 54 paintings, among them works by George Inness, Ralph Albert Blakelock, and Childe Hassam. Lang donated a collection of Native American art amassed by her mother, Annie Valentine Rand. The Rand Collection's several hundred objects included baskets, clothing, jewelry, and household items.[13]: 25, 28

The museum's holdings have expanded by means of acquisitions and donations. In 1922, the museum invited Montclair residents to vote for their favorite among 25 works for acquisition. The museum's art committee overrode the winning work by the impressionist Daniel Garber and instead purchased a work by the comparatively avant-garde Arthur Bowen Davies, Meeting in the Forest (1900), a depiction of nudes in a landscape in the Symbolist style.[29][30] In the 1930s the museum was less open to modernists,[31] and in the 1940s it tried to counter that reputation by having works for its annual exhibit of local artists' work selected by two juries, traditional and modern, a procedure abandoned when artists objected to having to characterize themselves in such a fashion.[32]

The building has since expanded along with the collection. The museum grew with additional gifts from Lang that allowed the front portico and mezzanine to be completed in 1924 and a new East Wing added in 1931 to house the Rand Collection. In the 1950s the high-ceilinged North Gallery was divided horizontally.[33] The most recent renovation by architectural firm Beyer Blinder Belle in 2000-2001 added a new wing that doubled the museum's square footage.[34]

To mark its 75th anniversary, MAM published Three Hundred Years of American Painting: The Montclair Art Museum Collection. It provided detailed entries for 538 paintings, detailed discussion of 32 of them, and a set of thematic essays.[35] In 1999, MAM collaborated on American Tonalism: Selections from the Metropolitan Museum of Art and the Montclair Art Museum.[36]

In January 2009, the museum announced it had transferred most of its LeBrun Library to the Harry A. Sprague Library at Montclair State University, a public institution that accepts library cards from public libraries in Essex and Passaic counties.[37][lower-alpha 7]

On occasion, MAM has mounted exhibits that bridge its interest in contemporary and Native American art. A 2001-2 exhibit explored Albert Bierstadt's depiction of encounters between European settlers and Native Americans, using its collection of Indian art to create conversations with two monumental Bierstadt oils.[40] In 2005, it presented "Roy Lichtenstein: American Indian Encounters" to explore a 20th-century American artist's fascination with and use of motifs from Native American art to critique their clichéd use by earlier artists. It included a Lichtenstein parody of Bierstadt, a variation on the Indian head nickel, and attempts to incorporate Indian symbolism into cubist and surrealist imagery.[41]

MAM also features exhibits that highlight its region. It participates with other institutions and the New Jersey State Council on the Arts in New Jersey Arts Annual: Fine Arts, which develops juried exhibitions of works by local artists. For example, as part of that program, in 2012 MAM presented 13 works that explored technology and "sampling, appropriating and remaking older artworks" in an exhibit called "New Media: New Forms".[42] In 2014, "Robert Smithson's New Jersey" explored how the artist's early exploration of the landscape and excavations near Paterson and Rutherford, New Jersey, inform Robert Smithson's later collages and land art projects. One critic wrote in The New Yorker: "This might seem like just more hopeful boosterism by a Garden State that exists in the shadow of a Big Apple, except that it’s true."[43]

In 2009, the museum and the Baltimore Museum of Art organized the exhibition "Cézanne and American Modernism," with 131 items, including 18 works by Cézanne. In a news release, MAM called the show "the largest, most ambitious exhibition in the 95-year history of the museum." After appearing in Montclair, the exhibition traveled to the Baltimore and to the Phoenix Art Museum.[44]

As its centennial year approached, MAM undertook a fundraising campaign to double its endowment to $20 million.[45] It also mounted an exhibition of contemporary sculpture based on the gifts of New Jersey resident Patricia A. Bell over the last 20 years to underscore its commitment to the contemporary arts scene.[46] To mark its centenary in 2014, on the anniversary date, it lit a new installation by Spencer Finch, Yellow, that filled the windows on the first level of the museum's facade with a soft glow that suggests someone is home, countering in some measure the formality of the architecture.[47][48]

Other programs

The museum's educational programs serve a wide public, from toddlers to senior citizens. Collaborations with numerous cultural and community partners bring artists, performers, and scholars to the museum on a regular basis. MAM's Yard School of Art is a regional art school offering an array of classes for children, youth, adults, seniors, and professional artists.[1]

In the summer of 2014, MAM launched a new community outreach program called the Art Truck, using an ice cream truck refurbished with funds from a grant from the Partners for Health Foundation. A pilot program in its first year, the Art Truck brought art instructors and supplies to conduct open studio art classes at sites in several New Jersey counties, including town pools, senior centers and assisted living facilities, local festivals, and farmers markets.[49][50]

Notes

- Realist painter George Bellows was, unlike the others, only a summer resident.[7]

- The Montclair Art Association continued under that name until 1962 when it adopted the name Montclair Art Museum.[15]

- Her philanthropy ranged from several institutions on Nantucket to Montclair High School and Scripps College in Claremont, California.[17]

- Three of her younger siblings had died by 1892.[20] Her uncle Addision died in 1900,[21] her father Jasper in 1909.[22] Her mother, already feeble, traveled to Italy and died in Milan in 1907.[23] She was buried in the Protestant Cemetery in Rome.[24] Florence's youngest and last remaining sibling died in 1909 at age 35 in Utah, where he was recuperating from pneumonia.[25]

- Ross later won the design competition for the Milwaukee County Courthouse in 1927, a competition that Frank Lloyd lost with some amusement.[26]

- The work depicts a folklore scene that even the sculptor admitted was dubious: a Sioux brave assesses a younger tribe member's effort to prove himself by shooting an arrow directly at the sun.[28]

- According to a 1999 account: "In 1913 the museum received a bequest from the estate of Michel LeBrun for the construction of a library and 40 volumes from his library for the LeBrun Library which opened in 1916, overseen by Michel's widow Maria Olivia LeBrun. In 1917, Michel's brother Pierre LeBrun, also an architect, donated an additional 100 volumes. Since the Montclair Art Museum's collection is limited to American fine arts and Native American art, the LeBrun Library's research materials are similarly restricted, for the most part, to these same fields. The LeBrun Library has been and still is the foremost art reference source in this limited field in the State of New Jersey. The library's holdings for its 84-year existence have increased more than one-hundred fold to some 14,000 books, plus some 5000 volumes of bound periodicals, 136 drawers of vertical file material on American artists, a collection of 20,000 slides, and nearly 8000 bookplates."[38][39]

References

- Montclair Art Museum: About, ARTINFO, 2008, retrieved July 21, 2008

- Schwabsky, Barry (February 16, 1997). "A Haven for Creative Talents, Then and Now". New York Times. Retrieved February 24, 2015.

- Web page titled "George Inness Gallery" at the Montclair Art Museum website, retrieved December 18, 2012

- Schwartz, Joel (1998). The Development of New Jersey Society. Trenton, N.J.: New Jersey Historical Commission. pp. 40–2.

- Schwabsky, Barry (February 16, 1997). "A Haven for Creative Talents, Then and Now". New York Times. Retrieved March 10, 2015.

- "Loan Exhibition at Montclair". New York Times. March 10, 1894. Retrieved March 10, 2015.

- Raynor, Viven (December 27, 1981). "The Magnet of Montclair". New York Times. Retrieved March 10, 2015.

- Carlisle, Robert D.B. (1982). A Jewel in the Suburbs: The Montclair Art Museum. Montclair, N.J.: Montclair Art Museum. pp. 19–20.

- Carlisle, Robert D.B. (1982). A Jewel in the Suburbs: The Montclair Art Museum. Montclair, N.J.: Montclair Art Museum. p. 16.

- Carlisle, Robert D.B. (1982). A Jewel in the Suburbs: The Montclair Art Museum. Montclair, N.J.: Montclair Art Museum. pp. 22–5.

- Rathbun, Richard (1909). The National Gallery of Art: Department of Arts of the National Museum. Washington: Government Printing Office. pp. 115ff. Retrieved February 27, 2015.

- "William T. Evans, Art Collector, Dies" (PDF). New York Times. November 26, 1918. Retrieved February 27, 2015.

- Carlisle, Robert D.B. (1982). A Jewel in the Suburbs: The Montclair Art Museum. Montclair, N.J.: Montclair Art Museum.

- Carlisle, Robert D.B. (1982). A Jewel in the Suburbs: The Montclair Art Museum. Montclair, N.J.: Montclair Art Museum. pp. 26–7.

- Carlisle, Robert D.B. (1982). A Jewel in the Suburbs: The Montclair Art Museum. Montclair, N.J.: Montclair Art Museum. p. 29.

- Carlisle, Robert D.B. (1982). A Jewel in the Suburbs: The Montclair Art Museum. Montclair, N.J.: Montclair Art Museum. pp. 25, 81.

- "Mrs. Henry Lang, A Patron of the Arts" (PDF). New York Times. February 6, 1943. Retrieved February 25, 2015.

- "Addison C. Rand" (PDF). New York Community Trust. Retrieved February 25, 2015.

- Rand, Florence Osgood (1898). A Genealogy of the Rand Family in the United States. NY: The Republic Press. p. 86ff.

- Rand, Florence Osgood (1898). A Genealogy of the Rand Family in the United States. NY: The Republic Press. p. 120.

- "Addison C. Rand" (PDF). New York Times. March 11, 1900. Retrieved February 27, 2015.

- "Obituary Notes" (PDF). New York Times. July 19, 1900. Retrieved February 27, 2015.

- "Obituary Notes" (PDF). New York Times. October 31, 1907. Retrieved February 25, 2015.

- "Protestant Cemetery, Rome: Stone 2153". Databank. Retrieved February 27, 2015.

- "Jasper Rand" (PDF). New York Times. April 1, 1909. Retrieved February 27, 2015.

- Wright, Frank Lloyd (1943). Frank Lloyd Wright: An Autobiography. Duell, Sloan and Pearce. p. 358. ISBN 9780764932434.

- Carlisle, Robert D.B. (1982). A Jewel in the Suburbs: The Montclair Art Museum. Montclair, N.J.: Montclair Art Museum. pp. 5, 14.

- "The Sun Vow, 1899". Metropolitan Museum of Art. Retrieved February 27, 2015.

- Carlisle, Robert D.B. (1982). A Jewel in the Suburbs: The Montclair Art Museum. Montclair, N.J.: Montclair Art Museum. p. 7.

- Charlotte Moser, "Davies, Arthur B." in Joan M. Marter, ed., The Grove Encyclopedia of American Art, Volume 1, 25-6

- Carlisle, Robert D.B. (1982). A Jewel in the Suburbs: The Montclair Art Museum. Montclair, N.J.: Montclair Art Museum. pp. 69, 72–3.

- Carlisle, Robert D.B. (1982). A Jewel in the Suburbs: The Montclair Art Museum. Montclair, N.J.: Montclair Art Museum. p. 88.

- Carlisle, Robert D.B. (1982). A Jewel in the Suburbs: The Montclair Art Museum. Montclair, N.J.: Montclair Art Museum. pp. 8, 32, 36, 46, 56–7, 127.

- D'Agnese, Joseph (November 4, 2001). "Big Dreams for the Montclair Art Museum". New York Times. Retrieved February 13, 2015.

- Marilyn S. Kushner, ed., Three Hundred Years of American Painting: The Montclair Art Museum Collection (The University of Chicago Press), reviewed by Elinor Nacheman in Art Documentation: Journal of the Art Libraries Society of North America, vol. 9, no. 2 (Summer 1990), p. 112; available online

- Kevin J. Avery and Diane P. Fischer, eds., American Tonalism: Selections from the Metropolitan Museum of Art and the Montclair Art Museum (Montclair Art Museum, 1999), reviewed by Martin Hopkinson in The Burlington Magazine, vol. 142, no. 1168 (July 2000), p. 453; available online

- "Montclair Art Museum - LeBrun Library". Sprague Library Digital Bookplates. Montclair State University. Retrieved February 13, 2015.

- Edith Anderson Rights, "Montclair Art Association", Libraries & Culture, vol. 34, no. 3 (Summer 1999), 278-281

- "Montclair Art Association". Bookplate Archive. University of Texas At Austin School of Information. Retrieved February 13, 2015.

- Zimmer, William (December 30, 2001). "In Montclair, a Controversial View of American History". New York Times. Retrieved February 24, 2015.

- Glueck, Grace (December 23, 2005). "A Pop Artist's Fascination With the First Americans". New York Times. Retrieved February 24, 2015.

- Schwendener, Martha (June 29, 2012). "Finding Inspiration in a Borrowed Past". New York Times. Retrieved March 7, 2015.

- Sullivan, Robert (June 18, 2014). "The Source of Robert Smithson's Spiral". The New Yorker. Retrieved March 6, 2015.

- "Cézanne and American Modernism". Yale University Press. Retrieved February 18, 2015. Published in conjunction with the exhibit: Gail Stavitsky and Katherine Rothkopf, eds., Cézanne and American Modernism (Yale University Press, 2009)

- "Montclair Art Museum Retains Ghiorsi & Sorrenti as Campaign Counsel". Ghiorsi & Sorrenti. Retrieved February 24, 2015.

- McGlone, Peggy (September 29, 2013). "Montclair Art Museum celebrates 100th anniversary with new sculpture, exhibits". NJ.com. Retrieved February 24, 2015.

- Ebbels, Kelly (January 9, 2014). "At the Montclair Art Museum, it's lights on for the party". Montclair Times. Retrieved February 13, 2015.

- "Montclair Art Museum Turns 100". NJTVonline.com. January 10, 2014. Retrieved February 13, 2015.

- Nutt, Bill (July 13, 2014). "Museum puts art on wheels". myCentralJersey.com. Retrieved March 2, 2015.

- Janulis, Tina (July 9, 2014). "Honk if You Love Art: MAM Art Truck Pulls into South Orange". The Village Green. Retrieved March 2, 2015.