The Three Perils of Woman

The Three Perils of Woman is a three volume work of one novel and two linked novellas by James Hogg. Following its original publication in 1823, it was omitted from Victorian editions of Hogg’s ‘’Collected Works’’ and re-published only in 2002.

The novellas depict events of the Jacobite rising of 1745 and the English reprisals under the Duke of Cumberland, while the novel depicts a woman with amnesia in Edinburgh during the 1820s.

Background

On 9 January 1823 Hogg indicated to William Blackwood that composition of a companion piece to The Three Perils of Man, which had appeared in June 1822, was well advanced: he had completed the first and by far the longest of its three fictions. He said that the project had been suggested by John Gibson Lockhart and that it had been begun in October.[1] It was completed during the first half of 1823, and on 11 August the publishers Longmans in London were expecting delivery of the printed copies from Edinburgh.[2]

Plot summary

The three perils are love, leasing (an old Scots term for lying) and jealousy.

Love

This part, which takes up the first two volumes, is set in about 1820 and is the story of Agatha (Gatty) Bell, the daughter of Daniel Bell, a sheep farmer in the Scottish Borders. Gatty meets and falls in love with M’Ion, a Highland aristocrat. Her feelings are reciprocated, but because of both parties’ extreme reticence and distaste for exposing their emotions, each comes to believe that the other detests them.

Gatty, who is in Edinburgh with Mrs Johnson, her old nurse (governess), living in an apartment in the same house as M’Ion (who turns out to be Mrs Johnson's illegitimate son), demands that her father take her home. He complies, and M’Ion proposes to and is accepted by Gatty’s friend Cherubina (Cherry) Elliot. By various shifts, Cherry is persuaded to relinquish M’Ion to Gatty, and M’Ion to declare his true love. Gatty and M’Ion are married, but Cherry dies and Gatty becomes convinced that she too is to die on a certain day. On the appointed day, Gatty falls into a catatonic suspended animation. She is taken to Edinburgh, where she recovers a degree of consciousness and activity and gives birth to a son, but has no memory of her prior life. She remains in this state for three years and on returning to her former mind is astonished to find herself the mother of a young son. M’Ion and her friends gently re-introduce her to the real world, and her story ends happily.

A comic sub-plot concerns Richard Rickleton, a good-natured but uncouth and impetuous farmer. Brought to Edinburgh as a suitor for Gatty when M’Ion is out of favour, he commits various solecisms, and when M’Ion and his friends - incited by the mischievous Joseph, Gatty’s brother - raise subjects of conversation which unwittingly offend him, becomes violent, and ends up in jail. Still enraged, he challenges M’Ion and his two friends to duels, in one of which he wounds M’Ion - the others not caring to face his anger. While ostensibly Gatty’s suitor, he also pays court to Katie M’Nab, whose forward manners are in complete contrast to Gatty’s.

After the end of Gatty’s story, Rickleton’s is completed. He marries Katie but three months later she leaves him to visit Edinburgh. He follows her and discovers she has just given birth to a child not his own. After a ludicrous pursuit of Katie’s seducer, involving mistaken identity and other errors, Rickleton decides to divorce Katie. However on one last visit, he forgives her and accepts the child as his own.

Leasing

This novella is set just before the Battle of Culloden (1746) in which the Jacobite forces were defeated and brutally scattered by the Hanoverian army. Sally Niven is an attractive and virtuous young woman, servant to the minister of her parish, and in love with Peter Gow the smith. Peter inadvertently shoots dead a man who is conducting an illicit burial in the churchyard, and Sally concocts a lie that he was preventing a grave robbery, which enables him to escape punishment. She is less successful with another lie: after her master, who has been terrified by being arrested and released, insists that she keep him company all one night, she tells Peter she was visiting elsewhere. But he has eavesdropped on them and so catches her in her lie. Their impending marriage is broken off.

The historical backdrop is the manoeuvres leading up to Culloden. Hogg places the action almost between the lines, in a menacing atmosphere of suspicion, allegations of treason and summary punishment without regard to guilt. In a humorous episode, Gow and a few followers rout a large body of pro-Hanoverian troops who mistake them in the dark for an army, panic and flee.

Jealousy

The final and shortest tale is set after Culloden and again has Sally and Peter as protagonists. Sally has married Alexander (Alaster) M’Kenzie, a noble Highlander who is proscribed by the English. They lose contact and set out to find each other. By mischance, they meet at a place where M’Kenzie’s cousins live, and Sally mistakes his affectionate leave-taking of a female cousin for lovemaking, assumes he has taken another lover and flees.

Meanwhile Peter, who has in the interim married an older woman, and is also a fugitive, meets with Sally. Aware that she is married, he does not offer her any familiarity, but escorts and protects her. This is misinterpreted by a witness who tells M’Kenzie that she has gone back to her old lover. M’Kenzie and Peter meet at an isolated cottage, both sure that the other has done them a mortal wrong. They fight and seriously wound each other. While they are recovering, tended by an increasingly demented Sally, Peter’s wife betrays them to the government forces and they are killed by a sergeant. Shepherds find Sally with a baby girl frozen to death on the grave of M'Kenzie and Peter.

Style and themes

In spite of the largely unrelieved tragedy of its third part, Three Perils contains more comedy than Hogg’s better-known Private Memoirs and Confessions of a Justified Sinner. In the first two stories, Hogg introduces buffoons (Rickleton, the minister, Daft Davie Duff the sexton) who provide comic relief. Humour also arises from the attempts of speakers of English, Scots and Gaelic to communicate. Hogg uses the conventions of the time to render the English pronunciation of Gaelic speakers. Hogg's modern editors note that some of this is true-to-life (e.g. consonantal shifts so that “By God!” becomes “Py Cot!”) but that most is literary convention.[3]

A unique feature of the work is the designation of the chapters as 'circles'. Hogg explains part at least of the reason for this at the end of 'Circle First' of 'Love': 'I like that way of telling a story exceedingly. Just to go always round and round my hero, in the same way as the moon keeps moving round the sun; thus darkening my plot on the one side of him, and enlightening on the other, thereby displaying both the lights and shadows of Scottish life'.[4]

Gatty's loss of awareness and/or memory is paralleled by that of Robert Wringhim in Private Memoirs and Confessions of a Justified Sinner. Wringhim discovers that he cannot account for six months of his life, in which by others' accounts he has been living a dissolute and vicious existence. In that case, however, the responsibility is apparently that of his alter ego Gil-Martin.

As a Lowland Scot, Hogg’s attitude to the Jacobite Rebellion is ambivalent. He recognises the virtues of the Highlanders and deplores the brutality of the English reprisals under the Duke of Cumberland, but towards the end of the book suggests that this is divine retribution for the atrocities committed on the Low Church Covenanters of southern Scotland in the 17th century.

The notorious Highland Clearances were in full swing in the period of action of 'Love', but are peripheral to its action, set in Edinburgh and the Borders. However Daniel's comment that he could make Highland estates profitable echoes the Clearances, in which small tenants were evicted to make way for large-scale sheep farming.

Editions

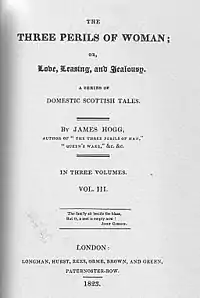

The work was first published by Longman, Hurst, Rees, Orme, Brown, and Green in London in August 1823, in three volumes. It was subsequently omitted from Hogg’s canon by Victorian editors. A possible reason is censorship, as Hogg dealt in a matter-of-fact way with issues such as prostitution and illegitimacy, which were still widely seen as unsuitable subjects for fiction when Wilkie Collins broached them 40 or more years later. The only clergyman to appear is ridiculed as a hypocrite, and Hogg draws no explicit moral from the vices of his characters.

A critical edition by David Groves, Antony Hasler, and Douglas S. Mack was published in 1995 by Edinburgh University Press as Volume 2 in the Stirling/South Carolina Research Edition of The Collected Works of James Hogg. The editors follow the first edition as the only authority. They argue that the work is of high quality and deserves to stand with the author’s Confessions in terms of critical acclaim.

Reception

Antony Hasler observes that the original reviews of The Three Perils of Women 'remain interesting, since their bafflement and disorientation are often a precise and sensitive register of what is […] a distinctly free-handed way with contemporary literary expectations'.[5] In an extensive analysis of the reviews, David Groves indicates that while there was appreciation of Hogg's stylistic vigour and flair for story-telling, his rich humour, and the power of his pathetic scenes, critics were disconcerted by what they took to be his coarse vulgarity and blasphemy, and by the instabilility of his characterisation.[6]

Further reading

- Leith Davis; Ian Duncan; Janet Sorensen (24 June 2004). Scotland and the Borders of Romanticism. Cambridge University Press. pp. 130–. ISBN 978-1-139-45413-1.

References

- The Collected Letters of James Hogg: Volume 2 1820‒1831, ed. Gillian Hughes (Edinburgh, 2006), 179.

- Gillian Hughes, James Hogg: A Life (Edinburgh, 2007), 193.

- James Hogg, The Three Perils of Woman, ed. David Groves, Antony Hasler, and Douglas S. Mack (Edinburgh, 1995), 443.

- Ibid., 25.

- Ibid., xiv.

- Ibid., 409‒19.