Estado Novo (Brazil)

The Estado Novo (English: New State), or Third Brazilian Republic, was a dictatorship established by Getúlio Vargas on November 10, 1937, which lasted politically until October 29, 1945 and formally until January 31, 1946. It was characterized by the centralization of power, nationalism, anti-communism and authoritarianism. It is part of the period in Brazilian history known as the Vargas Era.[1]

Republic of the United States of Brazil República dos Estados Unidos do Brasil | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1937-1946 | |||||||||

.svg.png.webp) Flag

Coat of arms

| |||||||||

| Motto: "Ordem e Progresso" "Order and Progress" | |||||||||

| Anthem: Hino Nacional Brasileiro (English: "Brazilian National Anthem") | |||||||||

.svg.png.webp) Brazil's territorial extension | |||||||||

| Capital | Rio de Janeiro | ||||||||

| Government | Authoritarian dictatorship | ||||||||

| President | |||||||||

• 1937–1945 | Getúlio Vargas | ||||||||

• 1945–1946 | José Linhares | ||||||||

| History | |||||||||

| 10 November 1937 | |||||||||

| 22 August 1942 | |||||||||

| 24 October 1945 | |||||||||

| 29 October 1945 | |||||||||

• Inauguration of Eurico Gaspar Dutra | 31 January 1946 | ||||||||

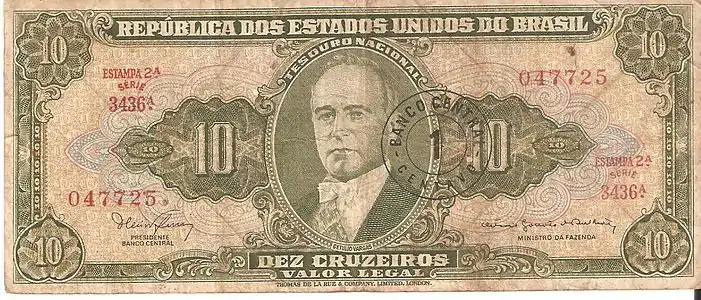

| Currency | Brazilian real (until 1942) Cruzeiro (after 1942) | ||||||||

| |||||||||

On November 10, 1937, through a coup d'état, Vargas instituted the Estado Novo via a Manifesto to the nation made in a radio address, in which he said that the regime intended to "readjust the political organism to the economic needs of the country".[2]

After the 1937 Constitution, Vargas consolidated his power. The government implemented press censorship and propaganda was coordinated by the Department of Press and Propaganda (DIP). There was also strong repression of communism, backed by the National Security Law, which prevented revolutionary movements, such as the Communist Uprising of 1935. The centralization of power and economic policy, along with a policy of import substitution, allowed funds to be raised for the advancement of industrialization in Brazil, and for the creation of institutions to make this process possible, such as the Companhia Siderúrgica Nacional and the Companhia Vale do Rio Doce.[3][4]

Later, the Estado Novo was also considered a precursor to the military dictatorship in Brazil, which began with the 1964 coup, although there are several differences between the two regimes.[5]

History

Background

On September 30, 1937, while awaiting the presidential elections scheduled for January 1938, which would be disputed by José Américo de Almeida, Armando de Sales Oliveira, both supporters of the 1930 revolution, and Plínio Salgado, the Vargas government denounced the existence of an alleged communist plan to seize power, which became known as the Cohen Plan. Later, Captain Olímpio Mourão Filho, a supporter of integralism, was accused of forging the plot. He was the same man who initiated the 1964 coup d'état in Brazil.[6]

However, the integralists deny their participation in the establishment of the Estado Novo, blaming General Góis Monteiro, then head of the Army General Staff, for the creation and dissemination of the Cohen Plan. Only eighteen years later, before the Brazilian Army's Council of Justification, requested on December 26, 1956, the then Colonel Olímpio Mourão Filho proved his innocence. On October 1, 1937, the day after the Cohen Plan was announced, the National Congress declared a state of war throughout the country.[6]

On October 19, the governor of Rio Grande do Sul, Flores da Cunha, after losing control of the Military Brigade of Rio Grande do Sul, which, by Getúlio's order, had been subordinated to the Brazilian Army, and after being surrounded militarily by General Góis Monteiro, left office and went into exile in Uruguay. Flores da Cunha, who had bought a large quantity of arms in Europe, represented the last possible military resistance to a coup attempt by Getúlio. Armando de Sales Oliveira, who could also oppose the coup d'état, had already left the government of São Paulo on December 29, 1936, to run for president. His successor José Joaquim Cardoso de Melo Neto promised Getúlio that "the state would not make another revolution". Just as in 1930, São Paulo was once again divided; the Constitutionalist Party (of Armando Sales and heir to the Democratic Party) and the Paulista Republican Party were unable to get along, since the PRP had not agreed to support Armando Sales' candidacy for the presidency of the republic.[6]

1937 coup

On November 10, 1937, through a coup d'état, Vargas instituted the Estado Novo via a Manifesto to the nation made in a radio address, in which he said that the regime intended to "readjust the political organism to the economic needs of the country". On the same day, he ordered the closure of Brazil's National Congress and granted a new constitution, which gave him total control of the executive branch and permission to appoint interventors for the states, to whom he gave broad decision-making autonomy. This statute, drafted by Francisco Campos, became known as "Polaca" because it was inspired by the constitution in force in Poland at the time.[7]

Consolidation

The 1937 Constitution provided for a new legislature, which was never installed, and for a plebiscite, that was not convened. During the Estado Novo, no elections were held, but the judiciary had its autonomy preserved. In its preamble, the document justifies the establishment of the dictatorship by describing a pre-civil war situation that Brazil was experiencing.[3]

On December 2, 1937, by Decree-Law No. 37, the political parties were abolished, including two that were critical of the political system then in force in Brazil and that preached "direct contact with the masses":[8]

Considering that the electoral system then in force, inadequate to the conditions of national life, based on artificial combinations of a legal and formal nature, encouraged the proliferation of parties, with the sole and exclusive aim of giving candidacies and elective positions the appearance of legitimacy, and:[8] Considering that the new regime, founded in the name of the nation to meet its aspirations and needs, must be in direct contact with the people, overriding partisan struggles of any kind, independent of the consultation of groupings, parties or organizations, ostensibly or disguisedly aimed at conquering public power.[8]

Regarding Getúlio's opinion on political parties, Luís Vergara says, in chapter 41 of his book Eu fui secretário de Getúlio, that Vargas was against their existence in the Estado Novo, even rejecting the one-party thesis:[9]

We must have no illusions. Given our customs and the low level of our political culture, addicted to oligarchic and personalist practices, this single party will soon begin to subdivide into factions and needlessly agitate and disrupt the life of the country.[9]

Getúlio added his government's vision to Luís Vergara: "What is urgent is to speed up the process of our development and strengthen the creative energies of progress and raising the economic level of the population, which, in many regions, remains stationary and in a stage of true pauperism." Luís Vergara then notes that "the issue (of the single party) is closed for good".[9]

The Estado Novo was also against any demonstration of regionalism. On December 4, the flags of the federal states, which were forbidden to have any symbols, were burned in a great civic ceremony on the Russel Esplanade in Rio de Janeiro. Getúlio expressed his opinion on this subject in 1939: "We no longer have regional problems; they are all national, and of interest to the whole of Brazil".[10]

The government implemented press censorship through the Department of Press and Propaganda (DIP), created by Decree-Law No. 1,915 of December 27, 1939. On the creation of the DIP, Getúlio, in a speech to the Federal Senate on December 13, 1946, stated:[11]

In 1940, and not in 1937, I created the Department of Press and Propaganda to control and closely monitor foreign infiltration in Brazil. At the time, the United Press and the Associated Press were operating in our country... Havas, which was French, was controlled by the Germans... Havas was the most widespread agency in Brazil and distributed the services of all the European agencies, including Reuter. Along with Havas, Transocean, directly German, covered the entire territory, blocking the United... Havas and Transocean distributed the national telegraph service. They had exceptional internal power. Several newspapers in German, Italian and Japanese infested the areas populated by these peoples.... British propaganda also intensified. But I shouldn't solve our problems according to the convenience of international propaganda, but on the basis of the convenience of Brazil and America... The excessive diligence of British propaganda repeatedly disrupted my actions. But to a certain extent it was useful, because it led to measures that guaranteed our impeccable neutrality (in the early years of the World War II).[12]

Getúlio's cabinet remained relatively stable during the Estado Novo, with the ministers of Finance, War, the Navy and Education remaining in their posts throughout the period. The only reaction to the establishment of the dictatorship was the Integralist Uprising on May 8, 1938, which attacked the Guanabara Palace with the aim of deposing Getúlio. This episode led Vargas to create a personal guard, which the people called the "Black Guard".[13]

In an interview with Revista do Globo, Getúlio gave his version of the Integralist Uprising: "First of all, it must be made clear that the Integralist coup of 1938 was organized by the German embassy. The Brazilians served only as instruments in a plan to hand the country over to the German government. Naturally, if it hadn't been for the help of German agents, they would never have carried it out, because they didn't have the capacity or the courage to do so."[14]

Political repression and torture

According to the preamble to the 1937 Constitution, the Estado Novo was installed in order to meet "the legitimate aspirations of the Brazilian people for political and social peace, deeply disturbed by notorious factors of disorder resulting from the growing aggravation of party disputes, that demagogic propaganda seeks to denature as class struggle, and the extremism of ideological conflicts, tending, by their natural development, to resolve themselves in terms of violence, placing the nation under the ominous imminence of civil war". It continues by saying:[3]

Attending to the state of apprehension created in the country by communist infiltration, which is becoming more extensive and deeper every day, requiring radical and permanent remedies;[3]

Given that, under the previous institutions, the State did not have the normal means to preserve and defend the peace, security and well-being of the people;[3]

Resolves to ensure to the Nation its unity, respect for its honor and independence, and to the Brazilian people, under a regime of political and social peace, the conditions necessary for their security, well-being and prosperity, by decreeing the following Constitution, which shall be fulfilled from today throughout the Country.[3]

Throughout the Estado Novo, there was rigorous repression of communism, backed by the National Security Law, and no revolutionary movements such as the Communist Uprising in 1935 occurred. However, there was no federal police force in Brazil, and the state police forces remained under the command of the federal interventors in the states. In civil life, the Brazilian Civil Code of 1916 remained in force, and a new, more liberal penal code was adopted.[15]

The strongest criticism of this repression concerns the torture that happened at the Rio de Janeiro Police Headquarters during Filinto Müller's administration. This fact spread the accusations by some critics of the Estado Novo, claiming that torture had occurred throughout Brazil, although nothing alleges that Getúlio knew about or ordered the torture.[16]

Regarding the Civil Police of the Federal District, on October 3, 1931, Getúlio reported on the changes he had made to that agency during his first year in office:[2]

Under the revolutionary government, the Civil Police of the Federal District redeemed itself in the eyes of public opinion; it was, in fact, one of the departments that had fallen the lowest in the country's general opinion. This division had long since ceased to be an apparatus of order, but had been transformed into a terrorist organization, whose fame had already spread, with the prestige of sinister things, beyond our borders.[2]

He reported on the measures taken in his first year in office:

The Provisional Government's action in the Civil Police went in two directions: the first was to uncompromisingly replace corrupt elements with others of proven suitability. Once the police mentality had been modified, however, another measure was needed: to remove it from subordinate influences, whether political or not, so that it would not suffer new deformations or deviations as the days went by.[2]

These reforms reported by Getúlio followed the suggestions of the Civil Police Reform Commission of the Federal District under the management of Police Chief João Batista Luzardo.[17]

Admiral Ernâni do Amaral Peixoto, who was federal interventor in the state of Rio de Janeiro during the Estado Novo, in his book Artes da Política - Diálogo com Amaral Peixoto, spoke about Captain Filinto Müller's work as a policeman: "Filinto was an excellent policeman. He was like Ramos de Freitas, whom I had to dismiss for excesses. The police in Filinto's time worked very well. Now it works the way he wants it to.[18]

In order to supervise the Civil Police of the Federal District, Decree-Law No. 5,504 of May 20, 1943, created the Federal District Police Inspectorate. The bad reputation of Civil Police of Rio de Janeiro in the Old Republic had already been celebrated in the first samba recorded in Brazil, Pelo Telefone, by Donga, in 1917, which read: "Over the phone, the Chief of Police tells me that in Carioca there's a roulette wheel to play".[19]

Several authors in their biographies have reported the imprisonment and torture they suffered, but without claiming the direct involvement of Getúlio Vargas. This is the case of Pagu, Carlos Marighella and Joaquim Câmara Ferreira, who lost his fingernails in prison.[20][21][22]

However, several artists directly accuse Getúlio of restricting individual rights and guarantees during the Estado Novo, a question he exposed in São Paulo on July 23, 1938: "The Estado Novo does not recognize the rights of individuals against the community. Individuals don't have rights, they have duties! Rights belong to the community! The state, overriding the struggle of interests, guarantees the rights of the community and enforces its duties towards it."[2][23]

Getúlio is accused of a variety of crimes and the Estado Novo is described as a regime of terror: "The Vargas regime's relentless persecution of its opponents (real and imagined), whose methods heavily involved the use of torture, violence, deportation and murder, was just one of the facets, perhaps the best known, of this period."[24]

Lawyer Marina Pasquini Toffolli says that "with the advent of the Estado Novo, which began in 1937, Brazil experienced a dictatorship that spread terror and built barbarism throughout its territory, suppressing all individual guarantees, closing the federal, state and municipal parliaments. It also established severe censorship of the press and greatly strengthened the police departments aimed at political and social repression."[25]

The American researcher R.S. Rose was the first civilian to spend months examining the secret police archives in the city of Rio de Janeiro. The material collected was included in the book One of the Forgotten Things: Getúlio Vargas and Brazilian social control - 1930-1954, published in Brazil in 2001 by Companhia das Letras. According to him, who sees the Estado Novo as an unpopular regime that needed to "coerce the people" in order to maintain itself, "during Vargas' rule, the quality and quantity of human rights abuses reached unprecedented levels. Violence, as a means of coercing the people, was evident in all sectors of the security apparatus... The nation's police forces redefined and in some cases reinvented the torture that had already taken place in Brazil since colonial times. The cruelty of their methods was matched only by the fervor with which this example was followed by subsequent generations."[26]

However, regarding Getúlio's popularity during the Estado Novo, the October 1954 special edition of the magazine O Mundo Ilustrado says that it was during the dictatorial period that he enjoyed his greatest popularity, stating that "the popular prestige of President Vargas grew even more after the proclamation of the Estado Novo. Never before has a head of state been so loved by his people in our country. His prestige never waned, and Vargas remained beloved until his tragic death."[27]

In the book Falta Alguém em Nuremberg: Torturas da Polícia de Felinto Strubling Müller, journalist David Nasser lists some of the most common forms of torture. In the 1952 novel Os Subterrâneos da Liberdade, the writer from Bahia Jorge Amado, who went into exile in 1948, relates "details of the repression of the Brazilian Communist Party, censorship, torture and imprisonment" during the Estado Novo; he was arrested twice, in 1936 and 1937, on charges of subversion for his involvement with the Communist Uprising.[28] In 1937, his books were burned in a public square in Salvador.[29] On the other hand, Tancredo Neves, who was Minister of Justice from 1953 to 1954, commented on Getúlio's actions as dictator in his book Tancredo Fala de Getúlio: "He tried hard to project himself in history as a unique dictator, because he was a progressive dictator, a humanitarian dictator. Despite one or two accusations of violence, the people don't accept Getúlio as a violent dictator".[30]

World War II

During World War II, in September 1939, Getúlio Vargas and the military maintained a neutral stance until 1941. Public opinion was divided: there was sympathy for the Axis Powers among many immigrants from those countries and integralists, but on the other hand, the majority of Afro-descendants and communists (especially after the invasion of the USSR in June 1941), who had great mobilization power and influence in the press, sympathized with the Allies. During this period, Getúlio wrote in his diary: "It seems to me that the Americans want to drag us into the war, without it being of any use to us or to them!"[6][31]

In January 1942, during the Pan-American Conference in Rio de Janeiro, the majority of countries on the continent condemned the Japanese attacks on the United States on December 7, 1941, and ended diplomatic relations with the Axis countries (Germany, Italy and Japan) on January 21, 1942. During the war, Nazi espionage in Brazil was active, both in networks and individual actions.[32]

The United States had plans to invade the northeastern region of Brazil, code-named Plan Rubber, if it didn't concede to the use of air bases in the north, which would compromise the country's neutrality. However, the execution of the plan wasn't necessary because, with or without Vargas' knowledge, the Brazilian military had already foreseen a "cautious alignment" with the US in the event of a new world conflict since 1934. In addition, the planned blockade imposed by the British navy on Germany and Italy made any kind of major exchange with these countries impossible.[33][34][35]

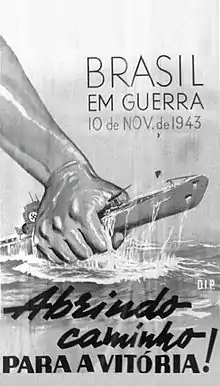

.png.webp)

After extensive negotiation, Brazil and the United States signed an agreement in which the US government committed to financing the construction of a large Brazilian steel plant (Companhia Siderúrgica Nacional) in Volta Redonda, Rio de Janeiro, in exchange for permission to set up military bases and airports in the north and northeast of the country and in Fernando de Noronha. Soon after, the German navy was authorized by Berlin to extend submarine warfare to merchant ships flying the Brazilian flag, which was followed by the Italian navy, effectively ending Brazil's neutrality. However, only on August 22, seven months after the attacks, did Getúlio declare war on Nazi Germany and Fascist Italy.[6]

The Allies needed natural rubber because, due to the Japanese occupation of Southeast Asia, they could no longer depend on a vital supply from that region. As a result, there was a large migration of northeastern Brazilians to the Amazon to extract rubber latex, reviving the area's economy in those years, which had stagnated since the end of the first rubber cycle decades earlier.[36]

On January 28, 1943, Vargas and Franklin D. Roosevelt, president of the United States, attended the Natal Conference, where the first agreements were made leading to the creation of the Brazilian Expeditionary Force (FEB) in August, a year after the declaration of war. The pracinhas, as the members of the FEB became known, numbered 25,000 men in 1945, out of a total initially estimated at 200,000. In July 1944, they were finally sent to fight in Italy, where they served from September of the same year until the end of the conflict in Europe on May 8, 1945. The US and the UK invited Brazil to take part in the occupation of Austria, but the FEB command refused.[37][38]

Decline

Among the FEB soldiers were eight law students from the University of São Paulo, who took part in peaceful demonstrations opposing Getúlio, such as the Silent March, in which they paraded with black gags to symbolize the lack of freedom of expression. "We were called up as a punishment - as if it could be a punishment to serve Brazil!" wrote one of these students, Geraldo Vidigal, in the book O Aprendiz de Liberdade - do Centro XI de Agosto à Segunda Guerra Mundial. The role of these students in the war was to disarm landmines before the tanks got through.[6][39]

Getúlio, in his diary on January 27, 1942, was already showing concerns about the future of the Estado Novo, stating that:[31]

I have to confess that I feel sad. A large part of those who applaud this attitude (breaking diplomatic relations with Germany), a few who even slander me, are opponents of the regime I founded (the Estado Novo), and I even doubt that I will be able to consolidate it in order to pass the government on to my replacement.[31]

In 1943, the first organized protest against the Estado Novo occurred in Minas Gerais, called the Manifesto dos Mineiros, written and signed by lawyers from the state, including many influential jurists and important political leaders of the UDN, such as José de Magalhães Pinto.[40]

A staunch opponent of the Estado Novo was the writer Monteiro Lobato, who was imprisoned and accused Getúlio of not letting Brazilians search for oil freely. As the World War II approached its end in 1945, the pressures for redemocratization grew stronger. José Américo de Almeida's interview with Carlos Lacerda on February 22, 1945, published in Rio de Janeiro's Correio da Manhã, symbolized the end of press censorship under the Estado Novo and the weakening and fall of the regime.[41]

Despite some measures taken, such as setting a date for the presidential elections on May 28, 1945 (December 2), amnesty for Luís Carlos Prestes and other political prisoners, freedom of party organization and the commitment to elect a new Constituent Assembly, the pressure for Getúlio to resign remained strong.[6]

Led by businessman Hugo Borghi, a movement in support of Getúlio emerged, which was nicknamed "Queremismo" with the slogans "Queremos Getúlio" (We want Getúlio) and "Constituinte com Getúlio" (Constituent with Getúlio), which wanted Vargas to remain in power until a new constitution was promulgated, but this did not happen.[42]

Getúlio Vargas was deposed on October 29, 1945 by a military movement led by generals who were part of his own ministry, putting an end to the Estado Novo.[1] He formally resigned as president of the republic and was replaced by the president of the Federal Supreme Court, José Linhares, since there was no vice-president in the 1937 Constitution. José stayed in office for three months before handing over power to the president elected on December 2, 1945, Eurico Gaspar Dutra. The trigger for the military action was the appointment of Getúlio's brother, Benjamim Vargas, as chief of police in Rio de Janeiro.[43]

A valuable contribution to Eurico Dutra's electoral victory came from Hugo Borghi, who distributed thousands of pamphlets accusing candidate Eduardo Gomes of saying: "I don't need the votes of the marmiteiros". In fact, what Eduardo said, at the Municipal Theater in Rio de Janeiro, on November 19, was: "I don't need the votes of these unemployed people who support the dictator to elect me president of the Republic".[44][45]

Economy and infrastructure

During the Estado Novo, the National Petroleum Council and the Administrative Department of Public Service were created by Decree-Law No. 579 of July 30, 1938, with the objective of reorganizing public administration, which was abolished by Decree No. 93,211 of September 3, 1986.[46] In his speech inaugurating the works of the Companhia Siderúrgica Nacional, Getúlio described this operation as a game-changer for the Brazilian economy and said: "The basic problem of our economy will soon be under a new sign. The semi-colonial, agrarian country, importer of manufactures and exporter of raw materials, will be able to shoulder the responsibilities of an autonomous industrial life, providing for its urgent defense and equipment needs."[47]

Vargas created the Companhia Nacional de Álcalis by Decree-Law No. 5.684 of July 20, 1943; the Companhia Vale do Rio Doce by Decree-Law No. 4.352 of June 1, 1942; and the Instituto de Resseguros do Brasil by Decree-Law No. 1. 186, of April 3, 1939. The São Francisco's Hydroelectric Company, the Federal Council for Foreign Trade, the law on joint-stock companies and the Estrada de Ferro Central do Brasil were reorganized as autarchies and their functions expanded, through Decree-Law No. 306 of May 24, 1941.[48][49][50][51]

Getúlio was a pioneer in the creation of the Brazilian aeronautical industry, creating the Fábrica Nacional de Motores (FNM), initially planned to be an aircraft factory, but later produced tractors and the FNM truck. Since 1933, he had also been personally involved in creating the Lagoa Santa Airplane Factory, in Minas Gerais, which faced difficulties due to the World War II and technical issues. It produced a few units of the T-6 aircraft and was closed in 1951.[52]

The Companhia Siderúrgica Nacional was created by Vargas after a diplomatic agreement, called the Washington Accords, between the Brazilian and US governments, which planned to build a steel mill that could supply the Allies with steel during the World War II. The agreements also established mutual cooperation with the United Kingdom in the war effort, with Brazil receiving loans and expanding exports of minerals and rubber. Decree-Law No. 4,523 of July 25, 1942, created the Commission for the Control of the Washington Agreements.[53]

The modernization of the armed forces included the creation of the Ministry of Aeronautics and the FAB, the construction of a new army headquarters, new barracks and military villages, the new military school in Resende (AMAN), the development of arms factories to reduce external dependence and new laws on the organization of the army, promotions, education, pension funds and the Code of Military Justice. The army of the time had eugenic criteria for selecting those who would do compulsory military service.[54]

The National Gasogen Commission encouraged the use of gasogen equipment to produce lean gas, which fueled Brazilian cars during the World War II, when imports of oil and derivatives were restricted. A new currency was created, the cruzeiro, which had been planned when Getúlio was Washington Luís' finance minister. Decree-Law 14 of September 25, 1937, created the Technical Council of Economy and Finance (CTEF) which, according to the newspaper Valor Econômico, was the "result of an exercise to supervise the country's financial conditions, carried out since the beginning of Getúlio Vargas' government".[55]

Decree-Law No. 395 of April 29, 1938, declared the national oil supply a public utility, granted the federal government exclusive competence to regulate the oil industry and created the National Petroleum Council. In 1939, in Lobato, Bahia, oil was extracted for the first time in Brazil. Decree-Law No. 311 of March 2, 1938, established rules on the territorial division of the country and, in Article 3, established that all municipal seats would have the category of cities.[56][57][58]

The Rio-Bahia highway, the first road link between central-southern and northeastern Brazil, was built and delivered. It extended as far as Feira de Santana and, from this city to Fortaleza, Getúlio constructed the Transnordestina Highway, now BR-116. About this road, Getúlio declared in the 1950 presidential campaign:[59]

In the first ten years following the 1930 Revolution, the road network in the Northeast almost doubled in length. The main routes linking the state capitals and the largest cities were almost all completed during my government. At the beginning of 1945, 1,234 kilometers of the great Transnordestina highway, which connects Fortaleza to Salvador and crosses the richest economic regions of Ceará, Pernambuco and the north of Bahia, were handed over to traffic.[59]

These roads greatly increased the migration of northeasterners to the center-south of Brazil, most of them coming in trucks nicknamed "paus-de-arara"; before their existence, journeys to the north were mainly made on ships called "itas". About the reservoirs Vargas built in the Northeast of Brazil, at a rally in Fortaleza on January 12, 1947, he said: "For almost half a century (from 1877 to 1930) only 650 million cubic meters of water were dammed to fight the drought. In 14 years, my government dammed almost three billion cubic meters of water and left works ready for another four billion cubic meters. In just over a decade, 10 times more than in half a century."[12]

The occupation of the Amazon by Brazilians from other regions, especially the Northeast, was stimulated by the extraction of rubber for export to the United States, which had lost its supply from Southeast Asia as a result of the World War II. These migrants, who became known as the "Rubber Soldiers", were inscribed in the Book of National Heroes by Law No. 12,447 of July 15, 2011.[60]

In 1944, Brazil took part in the Bretton Woods Conference, which resulted in the creation of the IMF and the World Bank. Decree-law 6.378, of March 28, 1944, transformed the Civil Police of Rio de Janeiro into the Federal Department of Public Security (DFSP), that in 1964 began to operate nationwide and in 1967 was renamed the Federal Police.[61] Decree-Law 7.293 of February 2, 1945, created Superintendence of Currency and Credit (SUMOC), stating in Article 1: "The Superintendence of Currency and Credit is created, directly subordinated to the Minister of Finance, with the immediate objective of exercising control over the monetary market and preparing the organization of the Central Bank." SUMOC exercised this function of currency control until the creation of the Central Bank of Brazil in 1964.[62]

Politics

.jpg.webp)

The political system was named Estado Novo after António de Oliveira Salazar's regime in Portugal, and lasted until October 29, 1945, when Getúlio Vargas was deposed by the Military.[63]

Vargas ordered the closure of the National Congress and the extinction of political parties. He granted a new constitution, which gave him total control of executive power and allowed him to appoint interventors in the states, to whom Getúlio gave wide autonomy in decision-making, and provided for a new legislature, but elections were never held during the Estado Novo.[6]

The 1937 Constitution was nicknamed the "Polaca", both to show that it had been largely influenced by Poland's authoritarian constitution and, in a depreciatory way, to associate it with a low-rent neighborhood in Rio de Janeiro. In practice, the document was not effective, as Getúlio ruled throughout the Estado Novo by decree-law and never called the plebiscite provided for in the text. The 1937 Constitution replaced the 1934 Constitution, which Vargas disliked.[7] On the 10th anniversary of the 1930 revolution, in a speech on November 11, 1940, he commented:

A hasty constitutionalization, out of time, presented as a solution to all ills, resulted in a political organization tailored to personal influences and factional partisanship, divorced from existing realities. It repeated the mistakes of the 1891 Constitution and aggravated them with provisions of pure legal invention, some retrograde and others nodding to exotic ideologies.[2]

In the version of Francisco Campos, who drafted the document, Vargas' mistake was not installing the legislative branch and not legitimizing himself by voting in a plebiscite. Since Francisco Campos said that he had started drafting the new constitution in 1936, it is suspected that the decision to carry out a coup d'état was taken shortly after the Communist Uprising, in November 1935.[64]

The Estado Novo promoted large patriotic, civic and nationalist demonstrations, encouraged by the Department of Press and Propaganda (DIP). The judiciary was not significantly interfered with during the Estado Novo, except in cases of political crimes, which is rare in strong political regimes.

Communist leader Luís Carlos Prestes remained imprisoned throughout the Estado Novo; due to his relationship with the Comintern, he defended the continuation of Getúlio Vargas' government during his speech at the São Januário Stadium in Rio de Janeiro in 1945, based on the progress achieved during his administration. The writer Monteiro Lobato was arrested for sending a letter to Getúlio criticizing his policy on Brazilian oil, as he wanted the government to exploit this natural resource for the country's development.[65][66]

However, the Estado Novo could take little action on the oil issue, as it was dependent on investments in research by foreign companies, which claimed that there was no such thing in Brazil. Faced with this situation, Getúlio Vargas decided to create the National Petroleum Council (CNP) during the Estado Novo and later, during his constitutional government, created Petrobras in 1953.[67]

During the regime, both militants from the National Liberation Alliance (ANL), a progressive and anti-fascist political group, and members of the Brazilian Integralist Action (AIB), a group inspired by Italian Fascism, were imprisoned. Important intellectuals were also arrested, such as the writer Graciliano Ramos and the journalist Barão de Itararé; some were not even oppositionists, but were victims of hateful accusations. The book Memórias do Cárcere by Graciliano Ramos is a hard-hitting account by the author of his experiences during the time he was imprisoned on Ilha Grande, accused of having links to the Communist Party (PCB).[68][69]

The press was censored. The morning newspaper O Estado de S. Paulo, which had a liberal ideology and supported the 1930 Revolution, was taken over from the Mesquita family by Adhemar Pereira de Barros. The newspaper's owner, Júlio de Mesquita Filho, went into exile in Argentina, and until today the journal does not count the years under Getulio's intervention in its official history; the company was returned to the Mesquitas in 1945.[1] The nationalization campaign was also launched to integrate immigrants and their culture into the national reality, reducing their influence and seeking their integration into the Brazilian population. During this period, teaching in a foreign language, which was very common in places of German colonization, was banned, and even the name of the Palestra Itália soccer club had to be replaced by Palmeiras.[70][71]

Decree-Law No. 483 of June 8, 1938, created the Brazilian Air Code to regulate air transport, which was in force until 1966, when it was replaced by another law of the same name.[72] Brazil's first comprehensive code on narcotics was created in Decree-Law No. 891 of November 25, 1938.[73] There was a spelling reform in 1943, which simplified the spelling of the Portuguese language, based on Decree-Law No. 292 of February 23, 1938. The Imperial Museum was created in Petrópolis by Decree-Law No. 2,096 of March 20, 1940.[74][75]

Socio-cultural policy

.jpg.webp)

Some of the Estado Novo's characteristics resemble Castilhism, of which Getúlio was a supporter. It had three basic principles valued by the Estado Novo: the choice of rulers based on their moral purity and not on their popular representativeness; in politics, party political disputes should be eliminated, valuing only virtue; the ruler should regenerate society, and the state should lead the transformation and modernization of society.[76]

In line with the national political tradition, Vargas and several members of his government were inspired by European fascism, from which they borrowed the contempt for political parties and the concern to efficiently control the press and education. For this purpose, the Department of Press and Propaganda (DIP) was created, which censored newspapers and produced propaganda pieces on behalf of the government, trying to turn Getúlio Vargas into a myth, as the "father of the poor".[1]

Like the Italian fascists, the Brazilian Estado Novo denied the class struggle, claiming that economic growth was on the side of businessmen and workers. Vargas appeased the workers by creating the CLT and setting up official unions, while he pleased the businessmen by creating infrastructure for the growth of industry. Due to his closeness to the lower classes, meeting their demands for certain rights, Getúlio Vargas was considered a populist.[1][77]

On the other hand, the Estado Novo sought a national identity for the first time in Brazil's history. The concept of "cultural anthropophagy" manifested by the Modern Art Week in São Paulo in 1922 was expanded during the Estado Novo through SPHAN, an institution planned by Mário de Andrade and with intellectual collaborators such as Carlos Drummond de Andrade, Oscar Niemeyer, Lúcio Costa and Cândido Portinari. The idea that there is an authentic Brazilian culture, created by the fusion of indigenous, African and European culture, was consolidated. Not just the three cultures, but the three peoples would live in harmony, creating a united people capable of modernizing the country.[78]

Civil and labor law

The Estado Novo promulgated the Brazilian Penal Code, the Law of Criminal Contraventions, the Brazilian Code of Criminal Procedure, and the Consolidation of Labor Laws (CLT), all in effect to this day. The Code of Civil Procedure was created, which at the time represented many advances, constituting the first modern procedural legislation in Brazil; it was abolished by the 1973 Code of Civil Procedure, established by Law 5.869, of January 11, 1973.[79] Decree-Law No. 1.985, of January 29, 1940, established the Mines Code, which was in force until 1967, when it was replaced by the Mining Code. Decree-law 7.661 of June 21, 1945 established the Bankruptcy Law, in force until 2005.[80] Decree-Law No. 2.994, soon replaced by Decree-Law No. 3.651, created the Brazilian Traffic Code.[81]

During the Estado Novo, Getúlio Vargas created the Labor Court on May 1, 1939, by Decree-Law 1,237, established the minimum wage and granted workers job stability after ten years of employment.[82] On November 28, 1940, the Inter-American Coffee Agreement was signed in Washington, DC, by Brazil and 13 other coffee-producing countries and the United States, with the aim of regulating coffee prices and international trade.[83]

In 1942, the territory of Fernando de Noronha was created. In 1943, the Federal Territory of Guaporé (now Rondônia), the Federal Territory of Rio Branco (now Roraima) and the Federal Territory of Amapá were established. The federal territories of Iguaçu and Ponta Porã were also founded, but did not prosper.[84][85] The decisive factor for Getúlio to create them was his visit, during the Estado Novo, to the Central-West of Brazil, when, as he says in his diary, he was impressed by the population vacuum in the region. He considered the Central Brazil of old to be "a vast, untapped solitude". In the process, he created indigenous reserves for the Guarani Kaiowá in order to remove them and facilitate this expansion.[86][87]

The north of Paraná, until then unpopulated, was colonized and filled with people through a major colonization project carried out by the private sector, especially by Companhia de Terras do Norte do Paraná (Cianorte). This effort to occupy the interior of Brazil was called by Getúlio the "March to the West"; in 1940, Cassiano Ricardo published a book with this title. Mining entrepreneur Jorge Abdalla Chamma, in his book Por um Brasil Melhor, details the Estado Novo's efforts to set up a steel plant in Corumbá.[88] On September 10, 1950, in his campaign for president of the republic, Getúlio made a speech in Uberaba attributing the development of the Triângulo Mineiro and Central Brazil to zebu cattle breeders:[59]

Fighting against opinions that opposed the introduction of zebu cattle in Brazil, the farmers of the Triângulo Mineiro, supported exclusively by their own work and their own resources, endured all the hardships of the tremendous struggle that was waged, and which, in the end, gave them an undisputed victory. Since then, Central Brazil has become economically significant, transforming it from the vast, untapped loneliness it was then into the large, economically active stronghold it is today.[59]

Decree-Law 5941 of 28 October 1943 established the Dourados National Agricultural Colony, which made it possible to colonize and expand agriculture in the south of what is now Mato Grosso do Sul. The Baixada Fluminense was cleaned up. Decree-Law No. 6882 of February 19, 1941 established the National Agricultural Colony of Goiás.[89][90]

Decree-Law No. 3,855, of February 21, 1941, established the Sugarcane Plantation Statute, which Getúlio described in a speech on January 12, 1947, in Recife: "The first agrarian reform law in Brazil came about for your benefit with the 'Sugarcane Plantation Statute'. I didn't promise it: I did it. I carried out the greatest social reform of the century with this statute, balancing real rights with labor rights."[91]

External policy

In the book A revolução e a América - O Presidente Getúlio Vargas e a Diplomacia (1930-1940), which brings together texts by Oswaldo Aranha and José Roberto de Macedo Soares, it is reported that when Getúlio took office in Brazil in 1930, he recognized and complied with all the commitments made by Brazil abroad, which facilitated diplomatic recognition of the Provisional Government.[92]

The government of Getúlio mediated the re-establishment of diplomatic relations between Peru and Uruguay; in 1931, it received a visit from Italian aviators and British princes; in 1934, it signed the Protocol of Friendship between Peru and Colombia, putting an end to the Leticia Question; it demarcated 4,535 kilometers of borders between 1930 and 1940; promoted conciliation between Bolivia and Paraguay, putting an end to the Chaco War, including forgiving the Paraguayan debt; obtained, through US President Franklin Roosevelt, a loan from the Export and Import Bank, used for public works and purchases for Lloyd Brasileiro and the Estrada de Ferro Central do Brasil; set up the Inter-American Neutrality Commission in Rio de Janeiro in 1940; signed 86 international acts and 122 bilateral agreements; created the Federal Foreign Trade Council in 1934; created the Immigration and Colonization Council in 1938 and the National Economy Defense Council in 1939.[93][94][95][96]

Getúlio Vargas employed ambiguous policies towards the Axis and Allied orbits. Firstly, Brazil seemed to be entering the Axis orbit even before the declaration of the Estado Novo in 1937. Between 1933 and 1938, Nazi Germany became the main market for Brazilian cotton, and its second largest importer of Brazilian coffee and cocoa. The rapid increase in civilian and military trade between Brazil and Nazi Germany gave US officials reason to start questioning Getúlio Vargas' international alignment.[97]

During the Estado Novo, Brazil sheltered many Jews persecuted by the Nazi-fascist regimes in Europe; João Guimarães Rosa, Brazil's consul in Germany, was posthumously honored by the Israeli government in the 1980s. Brazil was the only South American nation to found the League of Nations (1918) and the UN (1945), maintaining its traditional foreign policy of favoring negotiated solutions to conflicts.[98][99]

References

- "ESTADO NOVO". FGV CPDOC. Retrieved 2022-05-04.

- Vargas, Getúlio (1941). A nova política do Brasil. Livraria José Olympio.

- "CONSTITUIÇÃO DE 1937". Chamber of Deputies of Brazil. Retrieved 2021-03-07.

- Rodrigues, Natália. "Estado Novo". InfoEscola. Retrieved 2021-09-18.

- Azenha, Luiz Carlos (2014-03-27). "Fabio Venturini: No golpe dos empresários, a "mais beneficiada foi a Globo"". VioMundo.

- Corti, Ana Paula. "Estado Novo (1937-1945) - A ditadura de Getúlio Vargas". UOL. Retrieved 2012-11-10.

- "A constituição de 1937 – a "Polaca"". Politize. 2015-09-17. Retrieved 2023-09-18.

- "DECRETO-LEI Nº 37, DE 2 DE DEZEMBRO DE 1937". Federal government of Brazil. Retrieved 2023-09-18.

- Vergara, Luiz (1960). Fui Secretário De Getúlio Vargas. Globo.

- Vargas, Getúlio (1942). As diretrizes da Nova Política do Brasil. José Olímpio Editora.

- "DECRETO-LEI Nº 1.915, DE 27 DE DEZEMBRO DE 1939". Federal government of Brazil. Retrieved 2023-09-18.

- Vargas, Getúlio (1949). A Política Trabalhista do Brasil. Rio de Janeiro: José Olímpio Editora.

- "INTEGRALISTAS TENTAM DERRUBAR GETÚLIO". Memorial da Democracia. Retrieved 2023-09-18.

- Araújo, Eduardo Barreto de (2015). "As representações de Getúlio Vargas nas páginas da Revista do Globo (1929-1937): de gaúcho a chefe da nação" (PDF). UFSM.

- Barcellos, Daniela Silva Fontoura de. "UM BALANÇO DAS TENTATIVAS DE REFORMA DO CÓDIGO CIVIL NA ERA VARGAS". Publica Direito.

- Nogueira, André (2019-09-09). "FILINTO MÜLLER, O TORTURADOR DO ESTADO NOVO". UOL. Retrieved 2023-09-18.

- Monte Arrais (1970). O Estado Novo e suas Diretrizes. Livraria José Olympio.

- Camargo, Aspásia (1986). Artes da Política - Diálogo Com Amaral Peixoto. Nova Fronteira.

- "Pelo Telefone, o primeiro samba". Brasil Cultura. 2010-11-17.

- Silva, Luiz Henrique de Castro (2008). "O revolucionário da convicção: Joaquim Câmara Ferreira, o Velho Zinho". UFRJ.

- "Descubra quem é Marighella, ele foi considerado o inimigo nº1 da Ditadura Militar". Brasil Paralelo. 2022-08-18. Retrieved 2023-09-18.

- "Pagu". UOL. Retrieved 2023-09-18.

- "Na Bolsa de Mercadorias". Library of the Presidency of the Republic.

- "O que foi a Era Vargas?". UOL. Retrieved 2023-09-18.

- Toffoli, Marina Pasquini (2005-06-02). "Tortura".

- Rose, R. S. (2000). One of the Forgotten Things: Getulio Vargas and Brazilian Social Control, 1930-1954. Bloomsbury Academic. ISBN 9780313313585.

- "Special Complement". O Mundo Ilustrado. 1954.

- Amado, Jorge (1954). Os subterrâneos da liberdade. Livraria Martins Editora.

- Uchoa, Pablo (2017-11-26). "'Capitães da Areia': o dia em que o Estado Novo queimou um dos maiores clássicos da literatura brasileira". BBC. Retrieved 2023-09-18.

- Lima, Valentina da Rocha; Ramos, Plínio de Abreu (1986). Tancredo Fala De Getúlio.

- Vargas, Getúlio (1995). Diario de Getúlio Vargas (1 ed.). FGV.

- Silveira, Ari (2009-11-20). "Os espiões de Hitler no Brasil". Gazeta do Povo. Retrieved 2022-05-24.

- McCann, Frank (2007). Soldados da Pátria: História do exército brasileiro, 1889-1937. Companhia das Letras. ISBN 8535910840.

- Garfield, Seth. "In Search of the Amazon Brazil, the United States, and the Nature of a Region". Duke University Press. ISBN 9780822377177.

- Contreiras, Hélio (2011-08-08). "Invasão pelo Nordeste". Isto É. Retrieved 2010-11-17.

- Antonelli, Diego (2016-02-19). "Soldados da borracha: os escravos do século 20 em plena 2.ª Guerra Mundial". Gazeta do Povo. Retrieved 2023-09-18.

- Neher, Clarissa (2015-05-06). "EUA queriam que Brasil participasse da ocupaçã". Deutsche Welle. Retrieved 2019-03-18.

- Tosta, Wilson (2009-06-09). "País foi chamado a ocupar a Áustria". Estadão. Retrieved 2015-12-13.

- Vidigal, Geraldo de Camargo (1988). O aprendiz de liberdade: do Centro XI de Agosto à Segunda Guerra Mundial (1988). São Paulo: Saraiva.

- "Quando os mineiros se manifestam contra o Estado Novo, por Cláudia Viscardi". Blog BVPS. 2022-11-23. Retrieved 2023-09-18.

- Higa, Carlos César (2023-01-10). "A entrevista que "derrubou" a ditadura de Getúlio Vargas". Jornal Opção. Retrieved 2023-09-18.

- "Queremismo". UOL. Retrieved 2023-09-18.

- Pereira, Durval Lourenço (2022-12-28). "O Pracinha que Derrubou o Estado Novo". Memorial da FEB. Retrieved 2023-09-18.

- Borghi, Hugo (1995). A Força de um Destino. Forense Universitária. ISBN 9788521801399.

- "A primeira das grandes fake news". Correio do Povo. 2018-11-04. Retrieved 2023-09-18.

- "DECRETO-LEI Nº 579, DE 30 DE JULHO DE 1938". Federal government of Brazil. Retrieved 2023-09-18.

- "Vargas aos trabalhadores". O Mundo Ilustrado.

- "DECRETO-LEI Nº 3.306, DE 24 DE MAIO DE 1941". Federal government of Brazil. Retrieved 2023-09-18.

- "DECRETO-LEI Nº 5.684, DE 20 DE JULHO DE 1943". Federal government of Brazil. Retrieved 2023-09-18.

- "DECRETO-LEI Nº 4.352, DE 1º DE JUNHO DE 1942". Federal government of Brazil. Retrieved 2023-09-18.

- "Decreto-Lei nº 1.186, de 3 de Abril de 1939". Federal government of Brazil. Retrieved 2023-09-18.

- Braga, Paulo (2021-07-08). "O pioneirismo da origem da FNM no Brasil". Automotive business. Retrieved 2023-09-18.

- "DECRETO-LEI Nº 4.523, DE 25 DE JULHO DE 1942". Federal government of Brazil. Retrieved 2023-09-18.

- Gomes, Ana Carolina VImieiro; Silva, André Luiz dos Santos; Vaz, Alexandre Fernandez. "O Gabinete Biométrico da Escola de Educação Física do Exército: medir e classificar para produzir corpos ideais, 1930-1940". Hist. cienc. saude.

- "DECRETO-LEI Nº 14, DE 25 DE NOVEMBRO DE 1937". Federal government of Brazil. Retrieved 2023-09-18.

- "DECRETO-LEI Nº 395, DE 29 DE ABRIL DE 1938". Federal government of Brazil. Retrieved 2023-09-18.

- "DECRETO-LEI Nº 311, DE 2 DE MARÇO DE 1938". Federal government of Brazil. Retrieved 2023-09-18.

- Cruz, Leonardo (2019-10-04). "O óleo de Lobato: a primeira jazida de petróleo brasileira". Brasil de fato. Retrieved 2023-09-18.

- Vargas, Getúlio (1951). A Campanha Presidencial. José Olympio.

- "LEI Nº 12.447, DE 15 DE JULHO DE 2011". Federal government of Brazil. Retrieved 2023-09-18.

- "DECRETO-LEI Nº 7.293, DE 2 DE FEVEREIRO DE 1945". Federal government of Brazil. Retrieved 2023-09-18.

- "DECRETO-LEI Nº 6.378, DE 28 DE MARÇO DE 1944". Federal government of Brazil. Retrieved 2023-09-18.

- "Salazarismo em Portugal". Toda Materia. Retrieved 2023-09-18.

- "Intentona Comunista". UOL. Retrieved 2023-09-18.

- Barreiros, Isabela (2020-01-07). "EM 1941, MONTEIRO LOBATO FOI PRESO POR CRITICAR O ESTADO NOVO". Aventuras na História. Retrieved 2023-09-18.

- "A prisão de Luis Carlos Prestes" (PDF). A Federação (55 ed.). 1936-03-06.

- "Brasil cria Petrobras, em 1953, no embalo da campanha 'O petróleo é nosso'". O Globo. 2013-08-23. Retrieved 2023-09-18.

- Bernardo, André (2021-12-26). "Barão de Itararé: a vida trágica e o humor anárquico de um ícone do jornalismo". BBC. Retrieved 2023-09-18.

- "PRESO O ESCRITOR GRACILIANO RAMOS". Memorial da Democracia. Retrieved 2023-09-18.

- "Há 79 anos, pressão do governo fez Palestra Itália se tornar Palmeiras". Terra. 2021-09-14. Retrieved 2023-09-18.

- Mombach, Clarissa. "O GOVERNO VARGAS E SUAS IMPLICAÇÕES NA PRODUÇÃO LITERÁRIA TEUTO-BRASILEIRA" (PDF). Literatura e Autoritarismo. 10.

- "DECRETO-LEI Nº 483, DE 8 DE JUNHO DE 1938". Federal government of Brazil. Retrieved 2023-09-18.

- "DECRETO-LEI Nº 891, DE 25 DE NOVEMBRO DE 1938". Federal government of Brazil. Retrieved 2023-09-18.

- "DECRETO-LEI Nº 292, DE 23 DE FEVEREIRO DE 1938". Federal government of Brazil. Retrieved 2023-09-18.

- "DECRETO-LEI Nº 2.096, DE 29 DE MARÇO DE 1940". Federal government of Brazil. Retrieved 2023-09-18.

- "O castilhismo, nova luz sobre Getúlio Vargas". Espaço Democrático. 2020-09-08. Retrieved 2023-09-18.

- Jordão, Gibran (2023-05-01). "1º de maio: CLT faz 80 anos e vive seu pior momento". Esquerda Online. Retrieved 2023-09-18.

- "Cultura brasileira". UOL. Retrieved 2023-09-18.

- "LEI Nº 5.869, DE 11 DE JANEIRO DE 1973". Federal government of Brazil. Retrieved 2023-09-18.

- "DECRETO-LEI Nº 7.661, DE 21 DE JUNHO DE 1945". Federal government of Brazil. Retrieved 2023-09-18.

- "DECRETO-LEI Nº 2.994, DE 28 DE JANEIRO DE 1941". Federal government of Brazil. Retrieved 2023-09-18.

- "DECRETO-LEI Nº 1.237, DE 2 DE MAIO DE 1939". Federal government of Brazil. Retrieved 2023-09-18.

- Goes, Beatriz Augusta de Souza Vasconcelos (2006). "O Brasil e a formação do regime internacional do café". IRBr.

- "Território Federal de Ponta Porã". UOL. Retrieved 2023-09-18.

- "DECRETO-LEI Nº 5.812, DE 13 DE SETEMBRO DE 1943". Federal government of Brazil. Retrieved 2023-09-18.

- Brum, Eliane (2012-10-23). "Eliane Brum: "Decretem nossa extinção e nos enterrem aqui"". Vermelho. Retrieved 2023-09-18.

- Silva, Walter Guedes. "A ESTRATÉGIA DE INTEGRAÇÃO DO SUL DO ESTADO DE MATO GROSSO AO TERRITÓRIO NACIONAL DURANTE O GOVERNO VARGAS:UMA ANÁLISE A PARTIR DA CRIAÇÃO DA COLÔNIA AGRÍCOLA NACIONAL DE DOURADOS EM 1943". RDG. 31.

- Chamma, Jorge Abdalla (1955). Por Um Brasil Melhor. Rio de Janeiro: Clássica Brasileira.

- "Decreto nº 6.882, de 19 de Fevereiro de 1941". Federal government of Brazil. Retrieved 2023-09-18.

- "DECRETO-LEI Nº 5.941, DE 28 DE OUTUBRO DE 1943". Federal government of Brazil. Retrieved 2023-09-18.

- "DECRETO-LEI Nº 3.059, DE 14 DE FEVEREIRO DE 1941". Federal government of Brazil. Retrieved 2023-09-18.

- Aranha, Oswaldo; Macedo, José Roberto de (1941). A revolução e a América. O presidente Getulio Vargas e a diplomacia (1930-1940). DIP.

- Gomes, Rafael Nascimento (2019). "A DIMENSÃO REGIONAL DA POLÍTICA VARGUISTA: AS RELAÇÕES ENTRE BRASIL E URUGUAI DURANTE O ESTADO NOVO" (PDF). ANPUH.

- Rodrigues, Fernando da Silva; Zampa, VIvian (2020). "A Guerra Colombo-Peruana e o Exército Brasileiro (1932-1934): perspectivas e possibilidades de estudo para a nova história militar". Antiteses. 13 (26): 276–302. doi:10.5433/1984-3356.2020v13n26p276.

- Cano, Wilson (2005). "Getúlio Vargas e a formação e integração do mercado nacional" (PDF).

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - Carvalho, Gustavo Eberle de. "O Brasil e a geopolítica da Guerra do Chaco" (PDF). UNB.

- "Brasil na Segunda Guerra Mundial". UOL. Retrieved 2021-10-24.

- Fellet, João (2019-01-20). "A época em que o Brasil barrou milhares de judeus que fugiam do nazismo". BBC. Retrieved 2021-10-24.

- Garcia, Eugênio Vargas (1994). "A participação do Brasil na Liga das Nações (1919-1926)". UNB.

Bibliography

- Bertonha, João Fábio (2001). O Fascismo e os Imigrantes Italianos no Brasil. EdiPUC.

- Dalmáz, Mateus (2002). A Imagem do Terceiro Reich na Revista do Globo (1933 - 1945). EdiPUCRS.

- Garcia, Nelson Jahr (1982). Estado Novo - Ideologia e propaganda política. São Paulo: Loyola.

- Henriques, Affonso (1964). Vargas e o Estado Novo. Distribuidora Record.

- Lobato, José Bento Monteiro (1956). O escândalo de petróleo. Brasiliense.

- Silva, Hélio (1970). 1937 - Todos os Golpes Se Parecem. Civilização Brasileira.

- Vargas, Getúlio Dorneles (1939). A nova política do Brasil. José Olympio.