Third Servile War

The Third Servile War, also called the Gladiator War and the War of Spartacus by Plutarch, was the last in a series of slave rebellions against the Roman Republic known as the Servile Wars. This third rebellion was the only one that directly threatened the Roman heartland of Italy. It was particularly alarming to Rome because its military seemed powerless to suppress it.

| Third Servile War | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Servile Wars | |||||||

Italy and surrounding territory, 218 BC | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Rebel slaves | Roman Republic | ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 120,000 escaped slaves and gladiators, including non-combatants; total number of combatants unknown |

| ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

41,000 killed

| ~20,000 killed | ||||||

The revolt began in 73 BC, with the escape of around 70 slave gladiators from a gladiator school in Capua. They easily defeated the small Roman force sent to recapture them, and within two years, they had been joined by some 120,000 men, women, and children. The able-bodied adults of this large group were a surprisingly effective armed force that repeatedly showed they could withstand or defeat the Roman military, from the local Campanian patrols to the Roman militia and even to trained Roman legions under consular command. This army of slaves roamed across Italy, raiding estates and towns with relative impunity, sometimes dividing into separate but connected bands with several leaders, including the famous former gladiator Spartacus.

The Roman Senate grew increasingly alarmed at the slave-army's depredations and continued military successes. Eventually Rome fielded an army of eight legions under the harsh but effective leadership of Marcus Licinius Crassus that destroyed the army of slaves in 71 BC. This happened after a long and bitter fighting retreat before the legions of Crassus and after the rebels realized that the legions of Pompey and Marcus Terentius Varro Lucullus were moving in to entrap them. The armies of Spartacus launched their full strength against Crassus's legions and were utterly defeated. Of the survivors, some 6,000 were crucified along the Appian Way.

Plutarch's account of the revolt suggests that the slaves simply wished to escape to freedom and leave Roman territory by way of Cisalpine Gaul. Appian and Florus describe the revolt as a civil war in which the slaves intended to capture the city of Rome. The Third Servile War had significant and far-reaching effects on Rome's broader history. Pompey and Crassus exploited their successes to further their political careers, using their public acclaim and the implied threat of their legions to sway the consular elections of 70 BC in their favor. Their actions as consuls greatly furthered the subversion of Roman political institutions and contributed to the transformation of the Roman Republic into the Roman Empire.

Background

To varying degrees throughout Roman history, the existence of a pool of inexpensive labor in the form of slaves was an important factor in the economy. Slaves were acquired for the Roman workforce through a variety of means, including purchase from foreign merchants and the enslavement of foreign populations through military conquest.[1] With Rome's heavy involvement in wars of conquest in the 2nd and 1st centuries BC, from tens to hundreds of thousands of slaves at a time were imported into the Roman economy from various European and Mediterranean acquisitions.[2] While there was limited use for slaves as servants, craftsmen, and personal attendants, vast numbers of slaves worked in mines and on the agricultural lands of Sicily and southern Italy.[3]

For the most part, slaves were treated harshly and oppressively during the Roman republican period. Under Republican law, a slave was property, not a person. Owners could abuse, injure or even kill their own slaves without legal consequence. While there were many grades and types of slaves, the lowest—and most numerous—grades who worked in the fields and mines were subject to a life of hard physical labor.[4]

The large size and oppressive treatment of the slave population led to rebellions. In 135 BC and 104 BC, the First and Second Servile Wars erupted in Sicily, where small bands of rebels found tens of thousands of willing followers wishing to escape the oppressive life of a Roman slave. While these were considered serious civil disturbances by the Roman Senate, taking years and direct military intervention to quell, they were never considered a serious threat to the Republic. The Roman heartland had never seen a slave uprising, nor had slaves ever been seen as a potential threat to the city of Rome. This changed with the Third Servile War.

Beginning of the revolt (73 BC)

Capuan revolt

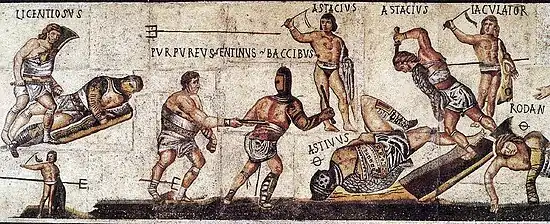

In the Roman Republic of the 1st century BC, gladiatorial games were one of the more popular forms of entertainment. In order to supply gladiators for the contests, several training schools, or ludi, were established throughout Italy.[5] In these schools, prisoners of war and condemned criminals—who were considered slaves—were taught the skills required to fight in gladiatorial games.[6] In 73 BC, a group of some 200 gladiators in the Capuan school owned by Lentulus Batiatus plotted an escape. When their plot was betrayed, a force of about 70 men seized kitchen implements ("choppers and spits"), fought their way free from the school, and seized several wagons of gladiatorial weapons and armor.[7]

Once free, the escaped gladiators chose leaders from their number, selecting two Gallic slaves—Crixus and Oenomaus—and Spartacus, who was said either to be a Thracian auxiliary from the Roman legions later condemned to slavery, or a captive taken by the legions.[8] There is some question as to Spartacus's nationality. A Thraex was a type of gladiator in Rome, so "Thracian" may simply refer to the style of gladiatorial combat in which he was trained.[9] On the other hand, names nearly identical to Spartacus were recorded among five out of twenty Thracian Odrysae rulers of Bosporan kingdom beginning with Spartokos I the founder of the Spartocid dynasty. The name came from the Thracian words *sparas "spear, lance" and *takos "famous" and thus meant "renowned by the spear".[10][11]

These escaped slaves were able to defeat a small force of troops sent after them from Capua, and equip themselves with captured military equipment as well as their gladiatorial weapons.[12] Sources are somewhat contradictory on the order of events immediately following the escape, but they generally agree that this band of escaped gladiators plundered the region surrounding Capua, recruited many other slaves into their ranks, and eventually retired to a more defensible position on Mount Vesuvius.[13]

Defeat of the praetorian armies

As the revolt and raids were occurring in Campania, which was a vacation region of the rich and influential in Rome, and the location of many estates, the revolt quickly came to the attention of Roman authorities. They initially viewed the revolt more as a major crime wave than an armed rebellion.

However, later that year, Rome dispatched a military force under praetorian authority to put down the rebellion.[14] A Roman praetor, Gaius Claudius Glaber, gathered a force of 3,000 men, not regular legions, but a militia "picked up in haste and at random, for the Romans did not consider this a war yet, but a raid, something like an attack of robbery."[15] Glaber's forces besieged the slaves on Mount Vesuvius, blocking the only known way down the mountain. With the slaves thus contained, Glaber was content to wait until starvation forced the slaves to surrender.

While the slaves lacked military training, Spartacus' forces displayed ingenuity in their use of available local tools, and in their use of clever, unorthodox tactics when facing the disciplined Roman infantry.[16] In response to Glaber's siege, Spartacus' men made ropes and ladders from vines and trees growing on the slopes of Vesuvius and used them to rappel down the cliffs on the side of the mountain opposite Glaber's forces. They moved around the base of Vesuvius, outflanked the army, and annihilated Glaber's men.[17]

A second expedition, under the praetor Publius Varinius, was then dispatched against Spartacus. For some reason, Varinius seems to have split his forces under the command of his subordinates Furius and Cossinius. Plutarch mentions that Furius commanded some 2,000 men, but neither the strength of the remaining forces, nor whether the expedition was composed of militia or legions, appears to be known. These forces were also defeated by the army of escaped slaves: Cossinius was killed, Varinius was nearly captured, and the equipment of the armies was seized by the slaves.[18]

With these victories, more and more slaves flocked to the Spartacan forces, as did "many of the herdsmen and shepherds of the region", swelling their ranks to some 70,000.[19] The rebel slaves spent the winter of 73–72 BC training, arming and equipping their new recruits, and expanding their raiding territory to include the towns of Nola, Nuceria, Thurii and Metapontum.[20]

The victories of the rebel slaves did not come without a cost. At some time during these events, one of their leaders, Oenomaus, was lost—presumably in battle—and is not mentioned further in the histories.[21]

Motivation and leadership of the escaped slaves

By the end of 73 BC, Spartacus and Crixus were in command of a large group of armed men with a proven ability to withstand Roman armies. What they intended to do with this force is somewhat difficult for modern readers to determine. Since the Third Servile War was ultimately an unsuccessful rebellion, no firsthand account of the slaves' motives and goals exists, and historians writing about the war propose contradictory theories.

Many popular modern accounts of the war claim that there was a factional split in the escaped slaves between those under Spartacus, who wished to escape over the Alps to freedom, and those under Crixus, who wished to stay in southern Italy to continue raiding and plundering. This appears to be an interpretation of events based on the following: the regions that Florus lists as being raided by the slaves include Thurii and Metapontum, which are geographically distant from Nola and Nuceria.[22]

This indicates the existence of two groups: Lucius Gellius eventually attacked Crixus and a group of some 30,000 followers who are described as being separate from the main group under Spartacus.[22] Plutarch describes the desire of some of the escaped slaves to plunder Italy, rather than escape over the Alps.[23] While this factional split is not contradicted by classical sources, there does not seem to be any direct evidence to support it.

Fictional accounts sometimes portray the rebelling slaves as ancient Roman freedom fighters, struggling to change a corrupt Roman society and to end the Roman institution of slavery. Although this is not contradicted by classical historians, no historical account mentions that the goal of the rebel slaves was to end slavery in the Republic, nor do any of the actions of rebel leaders, who themselves committed numerous atrocities, seem specifically aimed at ending slavery.[24]

Even classical historians, who were writing only years after the events themselves, seem to be divided as to what the motives of Spartacus were. Appian and Florus write that he intended to march on Rome itself[25]—although this may have been no more than a reflection of Roman fears. If Spartacus did intend to march on Rome, it was a goal he must have later abandoned. Plutarch writes that Spartacus merely wished to escape northwards into Cisalpine Gaul and disperse his men back to their homes.[23]

It is not certain that the slaves were a homogeneous group under the leadership of Spartacus, although this is implied by the Roman historians. Certainly other slave leaders are mentioned—Crixus, Oenomaus, Gannicus, and Castus—and it cannot be told from the historical evidence whether they were aides, subordinates, or even equals leading groups of their own and traveling in convoy with Spartacus' people.

Defeat of the consular armies (72 BC)

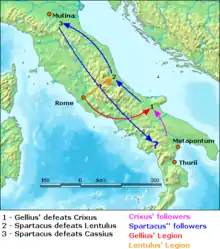

In the spring of 72 BC, the escaped slaves left their winter encampments and began to move northwards towards Cisalpine Gaul. The Senate, alarmed by the size of the revolt and the defeat of the praetorian armies of Glaber and Varinius, dispatched a pair of consular legions under the command of Lucius Gellius and Gnaeus Cornelius Lentulus Clodianus.[26] Initially, the consular armies were successful. Gellius engaged a group of about 30,000 slaves, under the command of Crixus, near Mount Garganus and killed two-thirds of the rebels, including Crixus.[27]

At this point, there is a divergence in the classical sources as to the course of events, which do not correspond until the entry of Marcus Licinius Crassus into the war. The two most comprehensive (extant) histories of the war by Appian and Plutarch detail very different events. Neither account directly contradicts the other but simply reports different events, ignoring some events in the other account and reporting events that are unique to that account.

Appian's history

According to Appian, the battle between Gellius' legions and Crixus' men near Mount Garganus was the beginning of a long and complex series of military maneuvers that almost resulted in the Spartacan forces attacking the city of Rome. After his victory over Crixus, Gellius moved northwards, following the main group of slaves under Spartacus who were heading for Cisalpine Gaul. The army of Lentulus was deployed to bar Spartacus' path and the consuls hoped to trap the rebel slaves between them. Spartacus' army met Lentulus' legion, defeated it, turned and destroyed Gellius' army, forcing the Roman legions to retreat in disarray.[28]

Appian claims that Spartacus executed some 300 captured Roman soldiers to avenge the death of Crixus, forcing them to fight each other to the death as gladiators.[29] Following this victory, Spartacus pushed northwards with his followers (some 120,000) as fast as he could travel, "having burned all his useless material, killed all his prisoners and butchered his pack-animals in order to expedite his movement".[28]

The defeated consular armies fell back to Rome to regroup while Spartacus' followers moved northwards. The consuls again engaged Spartacus at the Battle of Picenum somewhere in the Picenum region and were defeated again.[28] Appian claims that at this point Spartacus changed his intention of marching on Rome—implying this was Spartacus' goal following the confrontation in Picenum—as "he did not consider himself ready as yet for that kind of a fight, as his whole force was not suitably armed, for no city had joined him but only slaves, deserters, and riff-raff".[30] Spartacus decided to withdraw into southern Italy again. The serviles seized the town of Thurii and the surrounding countryside, arming themselves, raiding the surrounding territories, trading plunder with merchants for bronze and iron (with which to manufacture more arms) and clashing occasionally with Roman forces which were invariably defeated.[28]

Plutarch's history

Plutarch's description of events differs significantly from Appian's. According to Plutarch, after the battle between Gellius' legion and Crixus's men (whom Plutarch describes as "Germans") near Mount Garganus, Spartacus' men engaged the legion commanded by Lentulus, defeated it, seized the Roman supplies and equipment, then pushed into northern Italy.[31] After this defeat, both consuls were relieved of command of their armies by the Roman Senate and recalled to Rome.[32] Plutarch does not mention Spartacus engaging Gellius' legion at all, nor of Spartacus facing the combined consular legions in Picenum.[31]

Plutarch then goes on to detail a conflict not mentioned in Appian's history. According to Plutarch, Spartacus' army continued northwards to the region around Mutina (modern Modena). There, a Roman army of some 10,000 soldiers, led by the governor of Cisalpine Gaul, Gaius Cassius Longinus attempted to bar Spartacus' progress and was also defeated.[33] Plutarch makes no further mention of events until the initial confrontation between Marcus Licinius Crassus and Spartacus in the spring of 71 BC, omitting the march on Rome and the retreat to Thurii described by Appian.[32] As Plutarch describes Crassus forcing Spartacus' followers to retreat southwards from Picenum, it could be inferred that the rebel slaves approached Picenum from the south in early 71 BC, implying that they withdrew from Mutina into southern or central Italy for the winter of 72–71 BC. Why they might do so, when there was apparently no reason for them not to escape over the Alps—Spartacus' goal according to Plutarch—is not explained.[34]

The war under Crassus (71 BC)

Crassus takes command of the legions

Despite the contradictions in the classical sources regarding the events of 72 BC, there seems to be general agreement that Spartacus and his followers were in the south of Italy in early 71 BC. The Senate, alarmed at the apparently unstoppable rebellion, gave the task of putting it down to Marcus Licinius Crassus.[32] Crassus had been a field commander under Lucius Cornelius Sulla during the civil war between Sulla and the Marian faction in 82 BC and had served under Sulla during the dictatorship that followed.[35]

Crassus was given a praetorship and assigned six new legions in addition to the two formerly consular legions of Gellius and Lentulus, giving him an estimated army of some 32,000–48,000 trained Roman infantry plus auxiliaries (there being quite a range in the size of Republican legions).[36] Crassus treated his legions with harsh, even brutal, discipline, reviving the punishment of unit decimation within his army. Appian is uncertain whether he decimated the two consular legions for cowardice when he was appointed their commander or whether he had his entire army decimated for a later defeat (an event in which up to 4,000 legionaries would have been executed).[37]

Plutarch only mentions the decimation of 50 legionaries of one cohort as punishment after Mummius' defeat in the first confrontation between Crassus and Spartacus.[38] Regardless of events, Crassus' treatment of his legions proved that "he was more dangerous to them than the enemy" and spurred them on to victory rather than running the risk of displeasing their commander.[37]

Crassus and Spartacus

When the forces of Spartacus moved northwards once again, Crassus deployed six of his legions on the borders of the region (Plutarch claims the initial battle between Crassus' legions and Spartacus' followers occurred near the Picenum region, Appian claims it occurred near the region of Samnium).[32][39] Crassus detached two legions under his legate, Mummius, to maneuver behind Spartacus but gave them orders not to engage the rebels. When an opportunity presented itself, Mummius disobeyed, attacked the Spartacist forces and was routed.[38] Despite this initial loss, Crassus engaged Spartacus and defeated him, killing some 6,000 of the rebels.[39]

The tide seemed to have turned in the war. Crassus' legions were victorious in several more engagements, killing thousands of the rebel slaves and forcing Spartacus to retreat south through Lucania to the straits near Messina. According to Plutarch, Spartacus made a bargain with Cilician pirates to transport him and some 2,000 of his men to Sicily, where he intended to incite a slave revolt and gather reinforcements. He was betrayed by the pirates, who took payment and then abandoned the rebel slaves.[38] Minor sources mention that there were some attempts at raft and shipbuilding by the rebels as a means to escape but that Crassus took unspecified measures to ensure the rebels could not cross to Sicily and their efforts were abandoned.[40] Spartacus' forces retreated towards Rhegium, Crassus' legions following; upon arrival Crassus built fortifications across the isthmus at Rhegium, despite harassing raids from the rebel slaves. The rebels were under siege and cut off from their supplies.[41]

The end of the war

The legions of Pompey were returning to Italy, having put down the rebellion of Quintus Sertorius in Hispania. Sources disagree on whether Crassus had requested reinforcements or whether the Senate simply took advantage of Pompey's return to Italy but Pompey was ordered to bypass Rome and head south to aid Crassus.[42] The Senate also sent reinforcements under the command of "Lucullus", mistakenly thought by Appian to be Lucius Licinius Lucullus, commander of the forces engaged in the Third Mithridatic War but who appears to have been the proconsul of Macedonia, Marcus Terentius Varro Lucullus, the former's younger brother.[43] With Pompey's legions marching from the north and Lucullus' troops landing in Brundisium, Crassus realized that if he did not put down the slave revolt quickly, credit for the war would go to the general who arrived with reinforcements and he spurred his legions on to end the conflict quickly.[44]

Hearing of the approach of Pompey, Spartacus tried to negotiate with Crassus to bring the conflict to a close before Roman reinforcements arrived.[45] When Crassus refused, Spartacus and his army broke through the Roman fortifications and headed up the Bruttium peninsula with Crassus's legions in pursuit.[46] The legions managed to catch a portion of the rebels – under the command of Gannicus and Castus – separated from the main army, killing 12,300.[47]

Even though Spartacus had lost many men, Crassus' legions had also suffered greatly. The Roman forces under the command of a cavalry officer named Lucius Quinctius were destroyed when some of the escaped slaves turned to meet them.[48] The rebel slaves were not a professional army and had reached their limit. They were unwilling to flee any farther and groups of men were breaking away from the main force to independently attack Crassus's legions.[49]

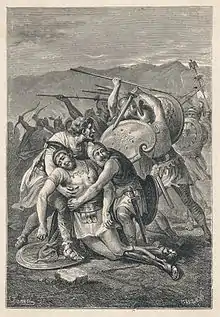

With discipline breaking down, Spartacus turned his forces around and brought his entire strength to bear on the legions. In this last stand, the Battle of the Silarius River, Spartacus' forces were routed, the vast majority of them being killed on the battlefield.[50] All the ancient historians stated that Spartacus was also killed on the battlefield but his body was never found.[51]

Aftermath

The rebels of the Third Servile War were annihilated by Crassus. Pompey's forces did not directly engage Spartacus's forces but his legions moving from the north were able to capture some 5,000 rebels fleeing the battle, "all of whom he slew".[52] After this action, Pompey sent a dispatch to the Senate, saying that while Crassus certainly had conquered the slaves in open battle, he had ended the war, thus claiming a large portion of the credit and earning the enmity of Crassus.[53] While most of the rebel slaves were killed on the battlefield, some 6,000 survivors were captured by the legions of Crassus. All 6,000 were crucified along the Appian Way from Rome to Capua.[45]

Pompey and Crassus reaped political benefit for having put down the rebellion; both returned to Rome with their legions and refused to disband them, instead camping outside Rome.[15] Both men stood for the consulship of 70 BC, even though Pompey was ineligible because of his youth and lack of service as praetor or quaestor.[54] Both men were elected consul for 70 BC, partly due to the implied threat of their armed legions encamped outside the city.[55][56]

It is difficult to determine the extent to which the events of this war contributed to changes in attitudes toward, use of, and legal rights accorded to Roman slaves. However, the end of the Servile Wars seems to have coincided with the end of the period of the most prominent use of slaves in Rome and the beginning of a new perception of slaves within Roman society and law.

Certainly the revolt had shaken the Roman people, who "out of sheer fear seem to have begun to treat their slaves less harshly than before".[57] The wealthy owners of the latifundia began to reduce the number of agricultural slaves, opting to employ the large pool of formerly dispossessed freemen in sharecropping arrangements.[58] With the end of Augustus' reign (27 BC – 14 AD), the major Roman wars of conquest ceased until the reign of Emperor Trajan (reigned 98–117 AD) and with them ended the supply of plentiful and inexpensive slaves through military conquest. This era of peace further promoted the use of freedmen as laborers in agricultural estates.

The legal status and rights of Roman slaves also began to change. During the time of Emperor Claudius (reigned 41–54 AD), a constitution was enacted that made the killing of an old or infirm slave an act of murder and decreed that if such slaves were abandoned by their owners, they became freedmen.[59] Under Antoninus Pius (reigned 138–161 AD), laws further extended the rights of slaves, holding owners responsible for the killing of slaves, forcing the sale of slaves when it could be shown that they were being mistreated and providing a (theoretically) neutral third party to which a slave could appeal.[60] While these legal changes occurred much too late to be direct results of the Third Servile War, they represent the legal codification of changes in the Roman attitude toward slaves that evolved over decades.

The Third Servile War was the last servile war and Rome did not see another slave uprising of this magnitude again.[61]

In popular culture

- The film Spartacus (1960), which was executive-produced by and starred Kirk Douglas, was based on Howard Fast's novel Spartacus and directed by Stanley Kubrick. The film's script was written by Dalton Trumbo, who had been blacklisted during the McCarthyism period of the 1950s. The film's success contributed to the collapse of the blacklist. The phrase "I'm Spartacus!" from this film has been referenced in a number of other films, television programs, and commercials.

- In 2004, Fast's novel was adapted as a made-for-TV movie by the USA Network, with Goran Višnjić in the main role.

- One episode of 2007–2008 BBC's docudrama Heroes and Villains features Spartacus.

- The television series Spartacus, starring Andy Whitfield, and later Liam McIntyre, in the title role, aired on the Starz premium cable network from January 2010 to April 2013.[62][63]

- The History Channel's Barbarians Rising (2016) features the story of Spartacus in its second episode entitled "Rebellion".

- The Netflix docudrama TV series Roman Empire features Spartacus as well as the Battle of the Silarius River in its 2nd season, recounting the story of Gaius Julius Caesar.

- The Third Servile War, and ancient slave revolts in general, play a central part in Arms of Nemesis by Steven Saylor.

References

Classical works

- Appian, Civil wars, Penguin Classics; New Ed edition, 1996. ISBN 0-14-044509-9.

- Caesar, Julius, Commentarii de Bello Gallico.

- Cicero, M. Tullius. The Orations of Marcus Tullius Cicero, literally translated by C. D. Yonge, "for Quintius, Sextus Roscius, Quintus Roscius, against Quintus Caecilius, and against Verres". London. George Bell & Sons. 1903. OCLC: 4709897

- Florus, Publius Annius, Epitome of Roman History. Harvard University Press, 1984. ISBN 0-674-99254-7

- Frontinus, Sextus Julius, Stratagems, Loeb edition, 1925 by Charles E. Bennett. ISBN 0-674-99192-3

- Gaius the Jurist, Gai Institvtionvm Commentarivs Primvs

- Livius, Titus, This History of Rome

- Livius, Titus, Periochae, K.G. Saur Verlag, 1981. ISBN 3-519-01489-0

- Orosius, Histories.

- Plutarchus, Mestrius, Plutarch's Lives, "The Life of Crassus" and "The Life of Pompey". Modern Library, 2001. ISBN 0-375-75677-9.

- Sallust, Histories, P .McGushin (Oxford,1992/1994) ISBN 0-19-872140-4

- Seneca, De Beneficiis

- Suetonius, Lives of the Twelve Caesars: The Life of Claudius.

Modern books

- Bradley, Keith. Slavery and Rebellion in the Roman World. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1989. ISBN 0-7134-6561-1.

- Broughton, T. Robert S. Magistrates of the Roman Republic, vol. 2. Cleveland: Case Western University Press, 1968.

- Davis, William Stearns ed., Readings in Ancient History: Illustrative Extracts from the Sources, 2 Vols, Vol. II: Rome and the West. Boston: Allyn and Bacon, 1912–13.

- Matyszak, Philip, The enemies of Rome, Thames & Hudson, 2004. ISBN 0-500-25124-X.

- Mommsen, Theodor, The History of Rome, Books I-V, Project Gutenberg electronic edition, 2004. ISBN 0-415-14953-3.

- Shaw, Brent. Spartacus and the Slave Wars: a brief history with documents. 2001.

- Smith, William, D.C.L., LL.D., A Dictionary of Greek and Roman Antiquities, John Murray, London, 1875.

- Strachan-Davidson, J. L. (ed.), Appian, Civil Wars: Book I, Oxford University Press, 1902 (repr. 1969).

- Strauss, Barry. The Spartacus War Simon & Schuster, 2009. ISBN 1-4165-3205-6.

Multimedia

- Fagan, Garret G., "The History of Ancient Rome: Lecture 23, Sulla's Reforms Undone", The Teaching Company. [sound recording:CD].

Notes

- References to the Mommsen text is based on the Project Gutenberg e-text edition of the books. References are therefore given in terms of line numbers within the text file, and not page numbers as would be the case with a physical book.

- References to "classical works" (Livy, Plutarch, Appian, etc.) are given in the traditional "Book:verse" format, rather than edition-specific page numbers.

- Smith, A Dictionary of Greek and Roman Antiquities, "Servus", p. 1038 Archived 2011-06-05 at the Wayback Machine; details the legal and military means by which people were enslaved.

- Smith, Greek and Roman Antiquities, "Servus", p. 1040 Archived 2012-10-05 at the Wayback Machine; Caesar, Commentarii de Bello Gallico, 2:33. Smith refers to the purchase of 10,000 slaves from Cilician pirates, while Caesar provides an example of the enslavement of 53,000 captive Aduatuci by a Roman army.

- Smith, Greek and Roman Antiquities, "Servus", p. 1039 Archived 2009-06-21 at the Wayback Machine; Livy, The History of Rome, 6:12

- Smith, Greek and Roman Antiquities, "Servus", pp. 1022–39 Archived 2013-07-26 at the Wayback Machine summarizes the complex body of Roman law pertaining to the legal status of slaves.

- Smith, Greek and Roman Antiquities, "Gladiatores", p. 574 Archived 2012-10-05 at the Wayback Machine.

- Mommsen, The History of Rome, 3233–3238.

- Plutarch, Crassus, 8:1–2; Appian, Civil Wars, 1:116; Livy, Periochae, 95:2 Archived 2018-11-07 at the Wayback Machine; Florus, Epitome, 2.8. Plutarch claims 78 escaped, Livy claims 74, Appian "about seventy", and Florus says "thirty or rather more men". "Choppers and spits" is from Life of Crassus.

- Appian, Civil Wars, 1:116; Plutarch, Crassus, 8:2. Note: Spartacus' status as an auxilia is taken from the Loeb edition of Appian translated by Horace White, which states "... who had once served as a soldier with the Romans ...". However, the translation by John Carter in the Penguin Classics version reads: "... who had once fought against the Romans and after being taken prisoner and sold ...".

- Smith, Greek and Roman Antiquities, "Gladiatores", p. 576 Archived 2012-10-10 at the Wayback Machine.

- Ivan Duridanov (Иван Дуриданов) (1985). Die Sprache der Thraker [The Language of the Thracians] (in German). Hieronymus Verlag. pp. 84–85. ISBN 978-3-928-28631-2.

- Vladimir I. Georgiev (1977). Траките И Техният Език [The Thracians and their Language] (in Bulgarian). Изд-во на Българската академия на науките. p. 95-96.

- Plutarch, Crassus, 9:1.

- Appian, Civil Wars, 1:116; Florus, Epitome, 2.8; – Florus and Appian make the claim that the slaves withdrew to Vesuvius, while Plutarch only mentions "a hill" in the account of Glaber's siege of the slave's encampment.

- Note: while there seems to be consensus as to the general history of the praetorian expeditions, the names of the commanders and subordinates of these forces varies widely based on the historical account.

- Appian, Civil Wars, 1:116.

- Frontinus, Stratagems, Book I, 5:20–22 and Book VII:6.

- Plutarch, Crassus, 9:1–3; Frontinus, Stratagems, Book I, 5:20–22; Appian, Civil Wars, 1:116; Broughton, Magistrates of the Roman Republic, p. 109. Note: Plutarch and Frontinus write of expeditions under the command of "Clodius the praetor" and "Publius Varinus", while Appian writes of "Varinius Glaber" and "Publius Valerius".

- Plutarch, Crassus, 9:4–5; Livy, Periochae , 95 Archived 2018-11-07 at the Wayback Machine; Appian, Civil Wars, 1:116; Sallust, Histories, 3:64–67.

- Plutarch, Crassus, 9:3; Appian, Civil War, 1:116. Livy identifies the second commander as "Publius Varenus" with the subordinate "Claudius Pulcher".

- Florus, Epitome, 2.8.

- Orosius, Histories 5.24.2; Bradley, Slavery and Rebellion, p.96.

- Plutarch, Crassus, 9:7; Appian, Civil Wars, 1:117.

- Plutarch, Crassus, 9:5–6.

- Historian Barry Strauss On His New Book The Spartacus War (Interview). Simon and Schuster. 2009. Archived from the original on 2021-12-22.

- Appian, Civil Wars, 1:117; Florus, Epitome, 2.8.

- Appian, Civil Wars, 1:116–117; Plutarch, Crassus 9:6; Sallust, Histories, 3:64–67.

- Appian, Civil Wars, 1:117; Plutarch, Crassus 9:7; Livy, Periochae 96 Archived 2017-07-19 at the Wayback Machine. Livy reports that troops under the (former) praetor Quintus Arrius killed Crixus and 20,000 of his followers.

- Appian, Civil Wars, 1:117.

- Appian, Civil war, 1.117; Florus, Epitome, 2.8; Bradley, Slavery and Rebellion, p.121; Smith, Greek and Roman Antiquities, "Gladiatores", p.574 Archived 2012-10-05 at the Wayback Machine. – Note that gladiator contests as part of some funeral rituals in the Roman Republic were a high honor, according to Smith. This accords with Florus' passage "He also celebrated the obsequies of his officers who had fallen in battle with funerals like those of Roman generals, and ordered his captives to fight at their pyres".

- Appian, Civil war, 1.117; Florus, Epitome, 2.8. Florus does not detail when and how Spartacus intended to march on Rome, but agrees this was Spartacus' ultimate goal.

- Plutarch, Crassus, 9:7.

- Plutarch, Crassus 10:1;.

- Bradley, Slavery and Rebellion, p. 96; Plutarch, Crassus 9:7; Livy, Periochae , 96:6 Archived 2017-07-19 at the Wayback Machine. – Bradley identifies Gaius Cassius Longinus as the governor of Cisalpine Gaul at the time. Livy also identifies "Caius Cassius" and mentions his co-commander (or sub-commander?) "Cnaeus Manlius".

- Plutarch, Crassus, 9:5.

- Plutarch, Crassus, 6; Appian, Civil Wars, 1:76–1:104. Plutarch gives a brief synopsis of Crassus's involvement in the war, with 6:6–7 showing an example of Crassus as an effective commander. Appian gives a much more detailed account of the entire war and subsequent dictatorship, in which Crassus's actions are mentioned throughout.

- Appian, Civil Wars, 1:118; Smith, A Dictionary of Greek and Roman Antiquities, "Exercitus", p.494 Archived 2012-10-06 at the Wayback Machine; Appian details the number of legions, while Smith discusses the size of the legions throughout the Roman civilization, stating that late republican legions varied from 5,000–6,200 men per legion.

- Appian, Civil Wars, 1:118.

- Plutarch, Crassus, 10:1–3.

- Appian, Civil Wars, 1:119.

- Florus, Epitome, 2.8; Cicero, Orations, "For Quintius, Sextus Roscius ...", 5.2

- Plutarch, Crassus, 10:4–5.

- Contrast Plutarch, Crassus, 11:2 with Appian, Civil Wars, 1:119.

- Strachan-Davidson on Appian. 1.120; Appian, Civil Wars, 1:120; Plutarch, Crassus, 11:2.

- Appian, Civil Wars, 1:120; Plutarch, Crassus, 11:2.

- Appian, Civil Wars, 1:120.

- Appian, Civil Wars, 1:120; Plutarch, Crassus, 10:6. No mention of the fate of the forces who did not break out of the siege is mentioned, although it is possible that these were the slaves under command of Gannicus and Castus mentioned later.

- Plutarch, Crassus, 11:3; Livy, Periochae, 97:1 Archived 2017-07-19 at the Wayback Machine. Plutarch gives the figure 12,300 rebels killed. Livy claims 35,000.

- Bradley, Slavery and Rebellion. p. 97; Plutarch, Crassus, 11:4.

- Plutarch, Crassus, 11:5;.

- Appian, Civil Wars, 1:120; Plutarch, Crassus, 11:6–7; Livy, Periochae, 97.1 Archived 2017-07-19 at the Wayback Machine. Livy claims some 60,000 rebel slaves killed in this final action.

- Appian, Civil Wars, 1:120; Florus, Epitome, 2.8.

- Matyszak, The Enemies of Rome p.133; Plutarch, Pompey, 21:2, Crassus 11.7.

- Plutarch, Crassus, 11.7.

- Appian, Civil Wars, 1:121.

- Appian, Civil Wars, 1:121; Plutarch, Crassus, 12:2.

- Fagan, The History of Ancient Rome; Appian, Civil Wars, 1:121.

- Davis, Readings in Ancient History, p.90

- Smitha, Frank E. (2006). "From a Republic to Emperor Augustus: Spartacus and Declining Slavery". Retrieved 2006-09-23.

- Suetonius, Life of Claudius, 25.2

- Gaius, Institvtionvm Commentarivs, I:52; Seneca, De Beneficiis, III:22. Gaius details the changes in the rights of owners to inflict whatever treatment they wished on their slaves, while Seneca details the slaves' right to proper treatment and the creation of a "slave ombudsman".

- Though there were other slave revolts in the future. See, e.g., Zosimus, Historia Nova, I.71.

- "Spartacus – Comic-Con 2009 - UGO.com". Tvblog.ugo.com. 29 June 2009. Archived from the original on 16 July 2012. Retrieved 24 February 2013.

- "AUSXIP Spartacus: Blood and Sand TV Show Lucy Lawless Sam Raimi & Rob Tapert". Spartacus.ausxip.com. Retrieved 24 February 2013.

External links

- Classical historical works

- Works at LacusCurtius.

- Appian's The Civil Wars.

- Frontinus's The Strategemata.

- Plutarch's, Life of Crassus

- Plutarch's, Life of Pompey

- Works at Livius.org.

- Appian on Spartacus Archived 2016-04-24 at the Wayback Machine (excerpts from The Civil Wars).

- Florus on Spartacus Archived 2016-03-03 at the Wayback Machine (excerpts from the Epitome of Roman History).

- Livy's Periochae. 95:2 Archived 2018-11-07 at the Wayback Machine.

- Livy's Periochae. 96:1 and 97:1 Archived 2017-07-19 at the Wayback Machine.

- Plutarch on Spartacus Archived 2018-02-16 at the Wayback Machine (excerpts from the Life of Crassus).

- Works at The Internet Classics Archive.

- Livy's Histories

- Modern works

- William Smith's, A Dictionary of Greek and Roman Antiquities at LacusCurtius.

- A scanned page version is also available at The Ancient Library.