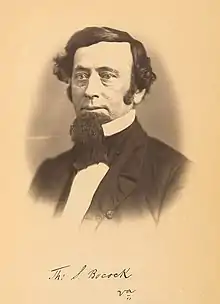

Thomas S. Bocock

Thomas Salem Bocock (May 18, 1815 – August 5, 1891) was a Confederate politician and lawyer from Virginia. After serving as an antebellum United States Congressman, he was the speaker of the Confederate States House of Representatives during most of the American Civil War.

Thomas Bocock | |

|---|---|

| |

| Speaker of the Confederate States House of Representatives | |

| In office February 18, 1862 – May 10, 1865 | |

| President | Jefferson Davis |

| Preceded by | Howell Cobb (President of the Provisional Congress) |

| Succeeded by | Position abolished |

| Member of the C.S. House of Representatives from Virginia's 5th district | |

| In office February 18, 1862 – May 10, 1865 | |

| Preceded by | Constituency established |

| Succeeded by | Constituency abolished |

| Member of the U.S. House of Representatives from Virginia | |

| In office March 4, 1847 – March 3, 1861 | |

| Preceded by | Paulus Powell |

| Succeeded by | William Goode |

| Constituency | 5th district (1847-1853) 4th district (1853-1861) |

| Member of the Virginia House of Delegates from Buckingham County | |

| In office December 5, 1842 – December 2, 1844 | |

| Preceded by | John W. Haskins |

| Succeeded by | Thomas H. Flood |

| Personal details | |

| Born | May 18, 1815 Buckingham, Virginia, U.S. |

| Died | August 5, 1891 (aged 76) Appomattox County, Virginia, U.S. |

| Political party | Democratic |

| Alma mater | Hampden–Sydney College |

Early and family life

Born at Buckingham County Court House in Buckingham County, Virginia, he was the sixth of eleven children born to John Thomas Bocock and Mary Flood. His mother was of a powerful and distinguished family which later produced Harry Flood Byrd and his father was a farmer, lawyer, clerk of the Appomattox County Court House and friend of Thomas Jefferson. Bocock was educated by his father and other private teachers as a child. He attended Hampden–Sydney College, where he befriended Robert L. Dabney (his rival for class valectedorian) and graduated in 1838.

His oldest brother, Willis Perry Bocock (1807-1887), may have been the most successful lawyer in the area (Buckingham County splitting off Appomattox county in 1845), as well as state attorney general beginning in 1852. Although Thomas' legal mentor, Willis resigned his official position and moved to Marengo County, Alabama in 1857 shortly after marrying Mourning Smith, a wealthy widow originally from South Carolina, although returning for family visits.[1] Another elder brother, John Holmes Bocock, became a Presbyterian minister in Lynchburg and then the District of Columbia.[2] A slightly younger brother, Henry Flood Bocock (b. 1817), also became a lawyer, clerk of the Appomattox County courthouse (at the time of Lee's surrender to Grant), director of Farmer's Bank in Lynchburg, as well as Presbyterian lay leader and later trustee of Hampden-Sydney College. Their brothers William Stevens Bocock, Charles Thomas Bocock, and Nicholas Flood married but did not have such distinguished careers, and Milton Bocock died as a teenager; their sisters Amanda, Martha, Mary Matson and Mary Fuquar all married.[3]

Thomas Bocock married his second cousin Sarah Patrick Flood in 1846, but she may have died in childbirth or from complications. They had a daughter Bell (1849-1891). His second wife was Annie Holmes Faulker. They married in Berkeley County, Virginia (later West Virginia) in 1853 and had five children: Thomas Stanley Bocock, Willis P Bocock (1861-1947) and daughters Mazie F., Ella F. and Sallie P. (all of whom married twice).[4]

Early legal career

Bocock studied law under his eldest brother and was admitted to the bar in 1840. He began his legal practice in Buckingham Court House, and was elected to the Virginia House of Delegates, where he served from 1842 to 1844. He was also the first prosecuting attorney for Appomattox County, Virginia when it split off Buckingham County, serving from 1845 to 1846.

Bocock was elected a Democrat to the United States House of Representatives in 1846, serving from 1847 to 1861. He became chairman of the Committee on Naval Affairs from 1853 to 1855 and again from 1857 to 1859. In 1859, Bocock was nominated for speaker of the House, but withdrew after eight weeks of debate and multiple ballots failed to elect a speaker.[5]

A committed slaveholder and Southern nationalist, Bocock praised Senator Preston Brook's attack on Charles Sumner, but later reinvented himself as a moderate on the Kansas slavery issue. Bocock spoke at the inauguration of the Washington Equine Statue on the grounds of the State Capital in Richmond in 1860, but his rise in Confederate circles came after his speech against Force Bill on February 20 and 21, 1861 which he had published and distributed at Virginia's Secession Convention.

Elections

- 1847; Bocock was elected to the U.S. House of Representatives with 51.42% of the vote, defeating Whig Henry P. Irving.

- 1849; Bocock was re-elected with 53.04% of the vote, defeating Whig Irving.

- 1851; Bocock was re-elected with 63.49% of the vote, defeating Whig Phillip A. Bolling.

- 1853; Bocock was re-elected with 51.74% of the vote, defeating Whig John T. Wootton and Independent Thomas H. Averett

- 1855; Bocock was re-elected with 57.25% of the vote, defeating American Nathaniel C. Claiborne .

- 1857; Bocock was re-elected unopposed.

- 1859; Bocock was re-elected with 88.78% of the vote, defeating two Independents identified only as Speed and Boisseau.

Civil War

Following the start of the Civil War and Virginia's secession, Bocock was elected as a Democrat to the Confederate States House of Representatives in 1861, serving until the end of the war in 1865. He was a member of the unicameral Provisional Confederate Congress, as well as the succeeding First and Second Confederate Congresses. Bocock was unanimously elected speaker of the Confederate States House of Representatives, and served from 1862 to 1865. However, in the final year, he broke with President Jefferson Davis and his personal friend and political ally Secretary of War James A. Seddon over the issue of arming slaves, arguing that such would be tantamount to abolishing slavery, as did his ally Robert M. T. Hunter. He left Richmond during the April 1865 evacuation, and later fled his home, the Wildway plantation.

Postwar career

As the war ended at nearby Appomattox Court House, Bocock owned more than twenty slaves. He did not want to pay his former slaves as workers, instead of telling them he would provide food and shelter, as he had under slavery. Bocock even tried to purchase several formerly enslaved people from neighbors. The African Americans appealed to the provost marshal, who said they deserved "liberal compensation."[6]

Bocock moved to Lynchburg while maintaining Wildway as his summer home, where he practiced law and helped form the Virginia Conservative Party. He supported President Andrew Johnson for election in 1868, and later unsuccessful Democratic Presidential candidates Horace Greeley in 1872 and Samuel Tilden in 1876.

One of the architects of Jim Crow Laws, Bocock served in Virginia's House of Delegates again from 1877 to 1879. He was a delegate to the Democratic National Conventions in 1868, 1876 and 1880. Bocock opposed the Virginia Readjuster Party and ultimately handed over the political reins to a younger generation, including Alexander H. H. Stuart, and concentrated on his legal practice and family.[7]

Death and legacy

He died in Appomattox County, Virginia, on August 5, 1891, and was interred at Old Bocock Cemetery near his plantation, Wildway.

Notes

- Marvel, William (February 12, 2008). A Place Called Appomattox. Southern Illinois University Press. ISBN 9780809328314.

- Charles F. Ritter and Jon Vakelyn, Leaders of the American Civil War: A Biographical and Historiographical Dictionary (Routledge, 2014) available on Google books

- Nathaniel R. Featherston, Appomattox County: History and Genealogy (Genealogical Publishing Company, 2009 at p. 114

- Featherston p. 114

- "Thomas S. Bocock". waymarking.com. Retrieved April 25, 2018.

- Remaking Virginia: Transformation through Emancipation. Exhibit at Library of Virginia beginning July 6, 2015

- Wakelyn (page numbering omitted in excerpt

References

- United States Congress. "Thomas S. Bocock (id: B000582)". Biographical Directory of the United States Congress. Retrieved on 2009-04-29