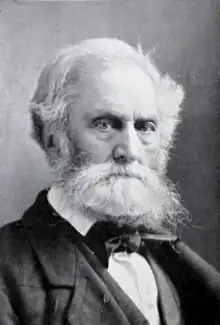

Thomas Green Clemson

Thomas Green Clemson (July 1, 1807 – April 6, 1888) was an American politician and statesman, serving as Chargés d'Affaires to Belgium, and United States Superintendent of Agriculture. He served in the Confederate Army and founded Clemson University in South Carolina. Historians have called Clemson "a quintessential nineteenth-century Renaissance man."[1]

Thomas Green Clemson | |

|---|---|

| |

| 4th United States Chargé d'Affaires to Belgium | |

| In office October 4, 1844 – January 5, 1852 | |

| President | John Tyler James K. Polk Zachary Taylor Millard Fillmore |

| Preceded by | Henry Washington Hilliard |

| Succeeded by | Richard H. Bayard |

| Personal details | |

| Born | July 1, 1807 Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, U.S. |

| Died | April 6, 1888 (aged 80) Clemson, South Carolina, U.S. |

| Spouse | Anna Maria Calhoun |

| Children | 4 including Floride |

| Education | Norwich University Collège de Sorbonne Royal School of Mines (Paris) |

| Occupation | Mining engineer Statesman Agriculturist College founder |

Life and education

Born in Philadelphia, Clemson was the son of Thomas Green Clemson III and Elizabeth Baker. He was descended from Quaker roots, and his mother was Episcopalian. Partly because of this mixed religious background, Clemson's personal religious belief is not well documented.[1] In 1813, his father died, and his father's second cousin, John Gest, was appointed guardian over him and his five siblings. Clemson was one beneficiary of his father's life savings of $100,000 ($1,516,207 today[2]), which was split among him and his siblings.[1] Little is known about his home life, but his schooling started in the winter of 1814, as he, as well as the older Clemsons, attended day school at Tabernacle Presbyterian Church. There is no knowledge as to exactly how long Thomas attended day school, but from 1823 to 1825, Clemson was educated at Alden Partridge's Military Academy in Vermont, also known as Norwich University.[1] Clemson's older brother, who had recently graduated from Princeton, sent Thomas a letter outlining the courses and subjects that he should study. He completed those studies sometime in late 1825, and returned to Philadelphia in 1825, where he started studying Mineralogy. Sometime in 1826 Clemson left for Paris, France.

Paris, France

His departure date, the ship name, and where he landed in France are unknown. Among the few surviving documents of his time in Paris is a letter that he wrote to his mother; it did not include anything about his scientific study, but did vaguely reference that he had a particular interest in expanding his knowledge. In addition, the letter states that if he were to die, all of his wealth should be left to his mother and then, after her death, it would be left to any of his unmarried sisters. In 1826–27, he expanded his knowledge of practical laboratory chemistry while working with chemist Gaultier de Clowbry and furthered his chemistry study by working with other Parisian chemists.[1] He further trained at Sorbonne and the Royal School of Mines. He received his diploma as an assayer from the Royal Mint.[3] In 1829, Clemson wrote a letter to Benjamin Silliman, M.D., about his research of iron ore. The date of his return to Philadelphia is unknown.[1]

In 1843, Thomas purchased a 1,000-acre plot of land in the Edgefield district in South Carolina. Named "Canebrake" (for the vast dense and thick canes along the riverbank), the land had an estimated value of $24,000.

Diplomat

With knowledge of both French and German, Clemson served as U.S. Chargé d'affaires to Belgium from 1844 to 1851. Clemson, through representation of the United States government, served as the Chargé d'affaires to Belgium starting October 4, 1844, and ending January 8, 1852. He received the position largely due to his father in-law John C. Calhoun, then Secretary of State under the Tyler Administration. President Tyler had given the task of filling the position to Calhoun, who quickly nominated his son in-law Clemson. Clemson was more than qualified to serve in this position for the government. From his time spent in Paris studying, he picked up on European culture and their way of living. In addition, the time there also gave him a feel for continental problems and thinking. With his extensive knowledge of not just Belgium's but the Europe's economics, politics, and social life, he was better able to connect the United States to Belgium and other European countries. The U.S. and Belgium signed a treaty during his time as chargé: the Treaty of Commerce and Navigation, which removed trade and tariff restrictions between the two countries for 10 years, boosting commerce.[4] Clemson was awarded the Order of Leopold by King Leopold I during his time as chargé.[5]

His South Carolina plot was not profitable while Clemson was abroad in Belgium, but he used the time to further his studies in the field of agriculture. He translated from French the lengthy article "Extraction of Sugar from the Beet," written by Professor Melsens, a professor at one of Belgium's State colleges.

Agricultural research

Upon his return from Belgium, Clemson chose to live in Maryland, not too far from Washington, D.C., for access to utilities and resources for his research, studies, and experiments. In 1853, he purchased a 100-acre plot in what is now Mount Rainier, Maryland, which he called "The Home." His studies in agricultural chemistry led to findings that were published in The American Farmer and other scientific journals. He attended the meetings of both the Maryland and the United States Agricultural Societies. Among other projects, he studied the cattle disease Texas Fever, demonstrating that cattle moving from the North to the South contracted the disease, whereas cattle going from the South to the North transmitted the disease. His findings and distinction as a scientist led to his invitation to speak at the Smithsonian Institution in Washington in 1858. Clemson was active in the field of agricultural research for many years to come, as more of his documents became published.[6]

From 1860 to 1861, Clemson served in the Buchanan administration as Superintendent of Agriculture.

American Civil War

As the threat of civil war became a reality, Clemson resigned this post on March 4, 1861. He stood on the side of his adopted state. Following the firing on Fort Sumter on April 12, 1861, Clemson left Maryland for South Carolina. In Pendleton on November 2, 1861, Clemson spoke to the Farmers Society and publicly "Urged the establishment of a department of agriculture in the government of the Confederate States which, in addition to fostering the general interest of agriculture, would also serve as a sort of university for the diffusion of scientific knowledge and the improvement of agriculture."

Fifty-four-year-old Clemson, enlisted in the Confederate States Army and was assigned to the Army of the Trans-Mississippi Department. Clemson worked in Arkansas and Texas developing nitrate mines for explosives. He was paroled on June 9, 1865, at Shreveport, Louisiana, after four years of service. His son, Captain John Calhoun Clemson, also enlisted in the Confederate States Army and spent two years in a Union prison camp on Johnson's Island, in Lake Erie, Ohio. He was a first lieutenant in the Confederate Army.

Marriage and family

On November 13, 1838, at the age of 31, Clemson married Anna Maria Calhoun, daughter of John C. Calhoun, the noted Senator from South Carolina and 7th Vice President of the United States and Floride Calhoun. After Calhoun's death, Floride Calhoun, Anna Calhoun Clemson, and two other Calhoun children inherited the Fort Hill plantation near Pendleton, South Carolina. It was sold for $49,000 (~$1.19 million in 2021) to Calhoun's oldest son, Andrew Pickens Calhoun, in 1854. After the war and upon Andrew's death in 1865, Floride Calhoun foreclosed on his heirs before her death in 1866. After lengthy legal procedures, Fort Hill was auctioned in 1872. The executor of her estate won the auction, which was divided among her surviving heirs. Her daughter, Anna Clemson, received the residence with about 814 acres (329.6 ha) and her great granddaughter, Floride Isabella Lee, received about 288 acres (116.6 ha). Thomas Green and Anna Clemson moved into Fort Hill in 1872. After Anna's death in 1875, Thomas Green Clemson inherited Fort Hill and lived there until his death. He died on April 6, 1888, and is buried in St. Paul's Episcopal churchyard in Pendleton, South Carolina.

Children

Thomas Green Clemson and his wife Anna Calhoun Clemson had four children. Their first child, whose name is not known, died as an infant in 1839. In 1841, John Calhoun Clemson was born. Shortly after in 1842, Anna Clemson gave birth to her daughter Floride Elizabeth Clemson. At age 15, John was getting treatment for a spinal condition in Northampton, Massachusetts. Another child, Cornelia "Nina" Clemson, was born in October 1855; she died in 1858 of scarlet fever. On July 23, 1871, their daughter Floride died. Clemson's only son John died three weeks later, on August 10, 1871.[1]

Founding Clemson University

Outliving his wife and his children, Clemson drafted a final will in the mid-1880s. The will called for the establishment of a land-grant institution called The Clemson Agricultural College of South Carolina upon the property of the Fort Hill estate. He believed that education, especially scientific education, leads to economic prosperity. He wanted to start an agricultural college because he felt that government officials did not appreciate the importance of agricultural education.[1]

Although the college was de facto an all-white, all-male college when it opened, Clemson did not explicitly ban women or African-Americans from attending, unlike the founders of Vanderbilt, Tulane, Rice and other southern universities.[7] However, Clemson's intent was no secret: he created the university because he believed South Carolina needed "an institution that vandal hands could not pollute," that is, a university that did not allow both blacks and whites to attend.[8]

The military college, founded in 1889, opened its doors in 1893 to 446 cadets. Clemson Agricultural College was renamed Clemson University in 1964. A statue of Thomas Green Clemson, as well as the Fort Hill house, are located on the campus. The town of Calhoun that bordered the campus was renamed Clemson in 1943.

References

- Bennett, Alma, ed. (2009). Thomas Green Clemson. Clemson, S.C.: Clemson University Digital Press. ISBN 978-0-9796066-8-7.

- 1634–1699: McCusker, J. J. (1997). How Much Is That in Real Money? A Historical Price Index for Use as a Deflator of Money Values in the Economy of the United States: Addenda et Corrigenda (PDF). American Antiquarian Society. 1700–1799: McCusker, J. J. (1992). How Much Is That in Real Money? A Historical Price Index for Use as a Deflator of Money Values in the Economy of the United States (PDF). American Antiquarian Society. 1800–present: Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis. "Consumer Price Index (estimate) 1800–". Retrieved May 28, 2023.

- Holmes, Alester (1937). Thomas Green Clemson: His Life and Works. Richmond VA: Garrett and Massie Incorporated.

- Holmes, Alester (1937). Thomas Green Clemson His Life and Work. Richmond, VA: Garrett & Massie, Inc. pp. 70–79.

- "Thomas Green Clemson", Clemson University, accessed March 5, 2012, http://www.clemson.edu/about/history/calhoun-clemson/thomasclemson.html

- Holmes, Alester (1937). Thomas Green Clemson His Life and Work. Richmond, VA: Garrett & Massie, Inc. pp. 91–98.

- "University celebrates Founder's Day with different look at Thomas Green Clemson » Anderson Independent Mail". Archived from the original on 2011-06-29. Retrieved 2010-04-06.

- Edgar, Walter, ed. The South Carolina Encyclopedia, University of South Carolina Press, 2006 ISBN 1-57003-598-9, p. 435

Bibliography

- Bennett, Alma (2009). Thomas Green Clemson. Clemson, South Carolina: Clemson University Digital Press.

- Edgar, Walter, ed. The South Carolina Encyclopedia, University of South Carolina Press, 2006 ISBN 1-57003-598-9, pp. 188–189.

- Holmes, Alester G. Thomas Green Clemson : His life and work (1937) Richmond, VA: Garrett and Massie, Inc.

- E. M. Lander, Jr., The Calhoun Family and Thomas Green Clemson: The Decline of a Southern Patriarchy (1983) University of South Carolina Press, Columbia, SC.