Thomas Ken

Thomas Ken (July 1637 – 19 March 1711) was an English cleric who was considered the most eminent of the English non-juring bishops, and one of the fathers of modern English hymnody.

Thomas Ken | |

|---|---|

| |

| Bishop of Bath and Wells | |

| Born | July 1637 Little Berkhampstead, Hertfordshire, England |

| Died | 19 March 1711 Longleat, Wiltshire, England |

| Venerated in | Anglican Communion |

| Major shrine | Church of St John the Baptist, Frome |

| Feast |

|

Early life

Ken was born in 1637 at Little Berkhampstead, Hertfordshire. His father was Thomas Ken of Furnival's Inn, of the Ken family of Ken Place, in Somerset; his mother was the daughter of little known English poet John Chalkhill. In 1646 Ken's stepsister, Anne, married Izaak Walton, author of The Compleat Angler, a connection which brought Ken under the influence of this gentle and devout man.[1]

In 1652 Ken entered Winchester College, and in 1656 became a student of Hart Hall, Oxford. He gained a fellowship at New College in 1657, and proceeded B.A. in 1661 and M.A. in 1664.[1] He was for some time tutor of his college; but the most characteristic reminiscence of his university life is the mention made by Anthony Wood that in the musical gatherings of the time Thomas Ken of New College, a junior, would be sometimes among them, and sing his part. Ordained in 1662, he successively held the livings of Little Easton in Essex, St. Mary's Church, Brighstone[2] in the Isle of Wight, and East Woodhay in Hampshire; in 1672 he resigned the last of these, and returned to Winchester, being by this time a prebendary of the cathedral, and chaplain to the bishop, as well as a fellow of Winchester College.

He remained there for several years, acting as curate in one of the lowest districts, preparing his Manual of Prayers for the use of the Scholars of Winchester College (first published in 1674), and composing hymns.[1] It was at this time that he wrote, primarily for the same body as his prayers, his morning, evening and midnight hymns, the first two of which, beginning "Awake, my soul, and with the sun" and "Glory to Thee, my God, this night", are well known. The latter is often made to begin with the line "All praise to Thee, my God, this night", which is how it appeared in a 1692 pamphlet printed by Richard Smith. However, this publication was likely made without Ken's permission, and subsequent editions over which he had control revert to "Glory to Thee, my God, this night". Both of these hymns end with a doxology beginning "Praise God, from whom all blessings flow," which is widely sung today by itself, often to the tune Old 100th.[3] "Awake, my soul, and with the sun" was included as Hymn 1 in the first edition of Hymns Ancient and Modern, while "Glory to Thee, my God, this night" was Hymn 10.[4]

In 1674 Ken paid a visit to Rome in company with his nephew, the young Isaac Walton (son of Ken's sister Anne and the writer Izaak Walton), and this journey seems mainly to have resulted in confirming his regard for the Anglican communion.[1]

Ken and Charles II

In 1679, Ken was appointed by Charles II chaplain to the Princess Mary, wife of William of Orange. While with the court at The Hague, he incurred the displeasure of William by insisting that a promise of marriage, made to an English lady of high birth by a relative of the prince, should be kept; and he therefore gladly returned to England in 1680, when he was immediately appointed one of the king's chaplains.[1]

He was once more residing at Winchester in 1683 when Charles came to the city with his slightly disreputable court. His residence was chosen as the home of Nell Gwynne, the King's official mistress. Ken stoutly objected and succeeded in making the favourite find quarters elsewhere.[5] In August of this same year he accompanied Lord Dartmouth to Tangier as chaplain to the fleet, and Pepys, who was one of the company, has left on record some quaint and kindly reminiscences of him and of his services on board.[1]

The fleet returned in April 1684, and a few months later, upon a vacancy occurring in the see of Bath and Wells, Ken was appointed bishop. It is said that, upon the occurrence of the vacancy, the King, mindful of the spirit he had shown at Winchester, exclaimed, "Where is the good little man that refused his lodging to poor Nell?" and determined that no other should be bishop. The consecration took place at Lambeth on 25 January 1685; and one of Ken's first duties was to attend the death-bed of Charles, where his wise and faithful ministrations won the admiration of everybody except Bishop Burnet.

In this year he published his Exposition on the Church Catechism, perhaps better known by its sub-title, The Practice of Divine Love.

Ken and James II

.jpg.webp)

In 1688, when James reissued his Declaration of Indulgence, Ken was one of the Seven Bishops who refused to publish it. He was probably influenced by two considerations: first, by his profound aversion to Roman Catholicism, to which he felt he would be giving some episcopal recognition by compliance; but, second and more especially, by the feeling that James was compromising the spiritual freedom of the church. Along with his six brethren, Ken was committed to the Tower on 8 June 1688, on a charge of high misdemeanour. Ken was put on trial with the others on 29 and 30 June, which resulted in a verdict of acquittal.[1]

The nonjuring schism

With the Glorious Revolution which speedily followed this impolitic trial, new troubles encountered Ken; for, having sworn allegiance to James, he thought himself thereby precluded from taking the oath to William of Orange. Accordingly, he took his place among the non-jurors, and, as he stood firm to his refusal, he was, in August 1691, superseded in his bishopric by Dr Richard Kidder, dean of Peterborough.[1]

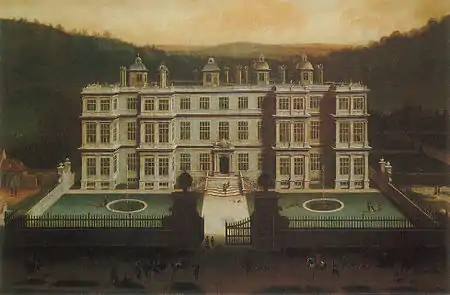

From this time he lived mostly in retirement, finding a congenial home with Lord Weymouth, his friend from college days, at Longleat in Wiltshire; and though pressed by Queen Anne to resume his diocese in 1703, upon the death of Bishop Kidder, he declined, partly on the ground of growing weakness, but partly no doubt from his love for the quiet life of devotion which he was able to lead at Longleat. He did however persuade George Hooper to accept and made a cession to him. At Hooper's instigation, Queen Anne granted Ken a pension of £200.[6] He died there on 19 March 1711, and at dawn the following day, whilst his faithful friends sang "Awake, my soul, and with the sun" Bishop Ken's remains were laid to rest beneath the East Window of the Church of St. John in Frome – the nearest parish in his old Diocese of Bath and Wells. "I am dying," Ken had written, "in the Holy, Catholic and Apostolic Faith professed by the whole Church before the disunion of East and West; and, more particularly, in the Communion of the Church of England, as it stands distinguished from both Papal and Puritan innovation, and adheres to the Doctrine of the Cross."[1]

Lodger at Longleat

When deprived of his see by William and Mary in 1691 after he refused to transfer his oath of allegiance from James, on the grounds that once given, it could not be forsworn, he was given lodgings at Longleat and an £80 annuity by Thomas Thynne, 1st Viscount Weymouth, a friend since Oxford days.

Taking up residence on the top floor at Longleat for a period of some twenty years, he exerted a profound influence upon Thomas Thynne, becoming what some might describe as his conscience. Thynne thus acquired a reputation for good deeds, which he himself regarded as spontaneous enough, but which the friends of his youth were inclined to regard as having been inspired by his devout friend, the Bishop.

An example of such benevolence: In 1707, Thynne, influenced by Ken, founded a grammar school for boys in the nearby market town of Warminster, with 23 free places for local boys. Originally The Lord Weymouth School (and known locally as The Latin School), in 1973 this school merged with St Monica's School for Girls to become the co-educational Warminster School, which continues to this day. Ken is remembered at Warminster School by the naming of a competitive 'house' after him.

Notable too is the fact that a portion of the West Wing of Longleat was transformed into a chapel for the household's daily worship. Not that its interior ever matched the architectural finery of equivalent chapels in other stately homes, but it was in any case evidence of the devout spirit which prevailed at Longleat over that particular historical period.

While living in the house at Longleat, Ken wrote many of his famous hymns, including 'Awake my soul', and, when he died in 1711, bequeathed his extensive library to the 1st Viscount.

Reputation and legacy

Although Ken wrote much poetry, besides his hymns, he cannot be called a great poet; but he had that fine combination of spiritual insight and feeling with poetic taste which marks all great hymn-writers. As a hymn-writer he has had few equals in England; he wrote Praise God from whom all blessings flow.[7][8] It can scarcely be said that even John Keble, though possessed of much rarer poetic gifts, surpassed him in his own sphere. In his own day he took high rank as a pulpit orator, and even royalty had to beg for a seat amongst his audiences; but his sermons are now forgotten. He lives in history, apart from his three hymns, mainly as a man of unstained purity and invincible fidelity to conscience, weak only in a certain narrowness of view. As an ecclesiastic he was a High Churchman of the old school.

Ken's poetical works were published in collected form in four volumes by W. Hawkins, his relative and executor, in 1721; his prose works were issued in 1838 in one volume, under the editorship of J. T. Round. A brief memoir was prefixed by Hawkins to a selection from Ken's works which he published in 1713; and a life, in two volumes, by the Rev. W. L. Bowles, appeared in 1830. But the standard biographies of Ken are those of John Lavicount Anderdon (The Life of Thomas Ken, Bishop of Bath and Wells, by a Layman, 1851; 2nd ed., 1854) and of Dean Plumptre (2 vols., 1888; revised, 1890). See also the Rev. W. Hunt's article in the Dictionary of National Biography.

He was buried at the Church of St John the Baptist, Frome, where his crypt can still be seen. He is also commemorated with a statue in niche 177 on the West Front of Salisbury Cathedral.

Thomas Ken is remembered in the Church of England with a Lesser Festival on 8 June.[9][10] He is also commemorated on the liturgical calendar of the Episcopal Church (USA) on 21 March.[11][12]

Writings

- A Manual of Prayer, (Winchester c. 1665) BiblioBazaar (2009) ISBN 978-1-110-03072-9

In literature

Thomas Ken appears in a number of novels:

- Iain Pears' An Instance of the Fingerpost (1997) includes Ken as a young fellow of New College, Oxford, desperate to be appointed to a parish through the college's patronage, so he can afford to marry.

- Robert Neill's historical novel Lillibullero (1975) depicts Ken as a devout and humane cleric attempting unsuccessfully to dissuade King James II from harsh retributions against the participants of the Monmouth Rebellion.

References

- Hunt 1892.

- "Three famous men of Brighstone" Sibley,P Brighstone, Church of St. Mary the Virgin, Brighstone ISBN 0-906328-31-4

- The Hymnal of the Protestant Episcopal Church in the United States of America (1940). New York: Church Pension Fund. # 139.

- Hymns Ancient and Modern (1861). London: Novello & Co.

- Southey, Robert (1812). "Bishop Kenn" Omniana, Longman London

- JWC Wand The High Church Schism, The Faith Press, 1951.

- The Hymnal of the Protestant Episcopal Church in the United States of America (1940). New York: Church Pension Fund. #139.

- Baptist Hymn Book (1962). Psalms and Hymn Trust, London.

- "The Calendar". The Church of England. Retrieved 27 March 2021.

- Common Worship: Services and Prayers for the Church of England (2000). London: Church House Publishing. p. 10.

- The Book of Common Prayer (1979). The Episcopal Church. New York: Church Publishing. p. 21.

- Lesser Feasts and Fasts (2018). The Episcopal Church. New York: Church Publishing. p. 143.

Sources

- Hunt, William (1892). Lee, Sidney (ed.). Ken, Thomas.

{{cite encyclopedia}}:|work=ignored (help) - This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Ken, Thomas". Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 15 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 726–727.