Thomas Prestbury

Thomas Prestbury (a.k.a. Thomas de Prestbury and Thomas Shrewsbury) was an English medieval Benedictine abbot and university Chancellor.

Thomas Prestbury | |

|---|---|

| Abbot of Shrewsbury | |

Shrewsbury Abbey | |

| Church | Catholic |

| Archdiocese | Province of Canterbury |

| Appointed | 1399 |

| Term ended | 1416 |

| Predecessor | Nicholas Stevens |

| Successor | John Hampton |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Possibly Prestbury, Cheshire |

| Died | 1426 Shrewsbury |

Origins

Prestbury is thought to have been born in the mid-1340s. The estimate is based on the assumption that he was about 24 in 1370, the year of his ordination to the priesthood.[1] There are many villages in England called Prestbury, but it is thought that of these the most likely place of birth would be Prestbury, Cheshire, near Macclesfield.

Monk and academic

Prestbury was ordained a subdeacon on 13 March 1367, marking the latest date he could have been admitted to Shrewsbury Abbey. He was made a deacon the following year on 3 June and a priest on 21 September 1370. He seems to have spent much of his early monastic career as a student.

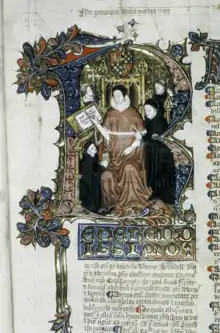

The general chapter of the English Benedictines had decreed that all abbeys maintain two monks at Oxford University during the 13th century. To achieve this Shrewsbury Abbey deployed funding from Wrockwardine parish church, which had been granted to it by Roger Montgomery shortly after its establishment, as noted in the Domesday Book.[2] In 1329 Edward III licensed the abbot to appropriate the church,[3] i.e. to take over the income stream of the benefice, essentially the tithes. In 1333, referring to the request of King Edward and Queen Philippa, the Pope issued a mandate confirming the abbey's appropriation, so long as enough was left over to support a perpetual vicar.[4] A late 15th century rent roll of the abbey shows the appropriation raising the reasonable sum of £17 6s. 8d. toward the support of two students, although the Valor Ecclesiasticus reckoned it at only £14. However, by that time it had long been customary to pay for only one, a fact bemoaned by critics of the abbey.[5] Prestbury evidently made the best of this funding, as he is known to have become a master of theology.'[6] It is not certain, however, that he was the Benedictine Thomas Scherusbury who was Chancellor of the University of Oxford in 1393-4: the identification is far from certain, although it appears as a fact in older sources, like Owen and Blakeway's History of Shrewsbury (1825).[7]

Throughout this period, the abbot at Shrewsbury was Nicholas Stevens, whose long incumbency from 1361 to 1399 enjoyed royal favour. A charter of Richard II, dated 10 February 1389, is said to be occasioned partly by "the sincere affection which we bear and have to Nicholas the abbot and for his merits." It is clear that the king had no such affection for Prestbury.

Election as Abbot

Prestbury was, as older and newer accounts agree, the Abbot of Shrewsbury Abbey from 1399 to 1426.[8] The circumstances of his election show that he was in some way involved in the conflicts of the time, when Richard II's authority, and ultimately kingship, were challenged by Henry Bolingbroke, although his precise rôle remains mysterious. On 6 April 1399 the king wrote to Stevens ordering Prestbury's detention.

- To the abbot of Shrewsbury. Order at his peril, to deliver brother Thomas master of theology, one of the monks his fellows, to the abbot of Westminster to be kept in custody until further order.[6]

A further note to the abbot added that he was to hand over Prestbury to John Lowell, serjeant at arms, for transfer to Westminster Abbey.[9] At the same time arrangements were made with the abbot of Westminster to imprison Prestbury.

- To the abbot of Westminster. Order at his peril, for particular causes specially moving the king, to receive Thomas a monk of Shrewsbury Abbey from one who shall deliver him, and as he will answer it to keep him in safe custody in Westminster Abbey until further order.[6]

Presumably Abbot Stevens died some time in the summer. The next report of Prestbury's detention comes from Adam of Usk, an important supporter of Bolingbroke, who accompanied his army on its triumphal progress from Bristol to Chester.

| Latin | English |

|---|---|

| Demum idem dux cum exercitu suo aput Herffordiam, secundo die Augustii, in palacio episcopi se hospitavit; et in crastino se versus Cestream movit, et in prioratu de Lempster pernoctavit. Et postea nocte proxima aput Lodelaw in castro regis, vino ibidem inhorriato non parcens, pernoctavit. Ubi presencium compilator ab eo et a domino Cantuariensi fratrem Thomam Prestburi, magistrum in theologia, ipsius contemporarium Oxonie, monachum de Salopia, tunc carceribus per regem Ricardum detentum, eo quod contra excessus suos quedam merito predicasset, ab huiusmodi carceribus liberari, et in abbatem monasterii sui erigi, optinuit. Demum per Salopiam transitus ibi per duos dies mansit; ubi fecit proclamari quod excercitus suus se ad Cestriam dirigeret, tamen populo et patrie parceret, eo quod per internuncios se sibi submiserant.[10] | At length the duke came to Hereford with his host, on the second day of August, and lodged in the bishop's palace; and on the morrow he moved towards Chester, and passed the night in the priory of Leominster. The next night he spent at Ludlow, in the king's castle, not sparing the wine which was therein stored. At this place, I, who am now writing, obtained from the duke and from my lord of Canterbury the release of brother Thomas Prestbury, master in theology, a man of my day at Oxford and a monk of Shrewsbury, who was kept in prison by king Richard, for that he had righteously preached certain things against his follies; and I also got him promotion to the abbacy of his house. Then, passing through Shrewsbury, the duke tarried there two days; where he made proclamation that the host should march on Chester, but should spare the people and the country, because by mediation they had submitted themselves to him.[11] |

If as Usk claims, he himself approached both Bolingbroke and Archbishop Thomas Arundel to secure Prestbury's release, the circumstance of their passing through Shrewsbury would explain the speed of his election. The monks requested royal approval for their election of Prestbury, still addressing themselves to Richard, on 11 August. Royal approval, now in the hands of Bolingbroke himself, came less than a week later.

- Signification to J. bishop of Coventry and Lichfield, of the royal assent to the election of Thomas de Prestbury, monk of St Peter's, Shrewsbury, to be abbot of that house.[12]

After some delay, as he presumably need to be fetched from Westminster, Prestbury was admitted as abbot on 4 September 1399.[7] The mandate to restore temporalities, accompanied by the writ de intendendo, instructing the tenants to transfer their loyalty to Prestbury, was issued from Westminster on 7 September.[13] As the abbots of Shrewsbury were tenants-in-chief of the king and had been summoned to parliament ever since the reign of Henry III,[14] Prestbury then had to attend parliament to deal with the business of deposing Richard II.[1]

Abbot of Shrewsbury

In 1403 the turmoil following the change of régime became particularly acute at Shrewsbury, which was the scene of a major conflict between Henry IV and a coalition led by his former allies, the House of Percy. The Battle of Shrewsbury was waged on a site just to the north of the town and abbey: a location still called Battlefield. According to Thomas Walsingham, Prestbury and another cleric, a clerk of the Privy Seal, went on a peace mission to the rebels, offering Henry Hotspur "peace and pardon if he would refrain from opening" hostilities.[15] Walsingham attributes the failure of this effort to the deception of Hotspur's uncle, Thomas Percy, 1st Earl of Worcester. Earl Thomas was beheaded after the battle.[16] In December Prestbury was instructed to recover his head, on display at London Bridge, and have it buried in Shrewsbury Abbey with his body.[1] The disorder, which included the depredations of Owain Glyndŵr's troops, was such that on 20 May 1405 the abbey was dispensed, during Prestbury's lifetime, from paying the tenths, a key royal tax, on its properties outside the Diocese of Lichfield because of the damage done by to its lands by Welsh rebels.[17] On 5 December 1405 Prestbury was granted a licence for 20 marks to take into mortmain six properties in Shrewsbury with an annual value of 6 marks:[18] the first of a number of small acquisitions for the abbey.

The Victoria County History argues that the appointment of Prestbury as abbot after Richard II's imprisonment is "a circumstance suggesting that Prestbury favoured the Lancastrians."[19] ODNB, however, concedes only that Prestbury became a firm supporter of Bolingbroke after he became king.[1] Usk makes clear that Thomas Arundel's approval was significant in winning the support of the new régime for Prestbury and the most important centre of power in Shropshire was the Arundel affinity, centred on the Archbishop's nephew, Thomas FitzAlan, 12th Earl of Arundel, certainly the most important magnate in the region.[20]

Although the precise scope of the Arundel affinity is unknown, it is known to have included at least half the Members of Parliament elected in Shropshire in the period 1386–1421. Prestbury made a few small acquisitions of property in Shrewsbury during his abbacy and one of them was a house known as "Ireland Hall." Royal permission to accept this burgage was sought in July 1407 by Prestbury and the convent of Shrewsbury Abbey.[21] The donors included four gentry members of the Arundel affinity, probably acting on the Earl's behalf:[22] Robert Corbet, his younger brother Roger, their aunt's husband John Darras and William Ryman of Sussex. Some of these were very violent men. Darras, an experienced soldier in the campaigns against Owain Glyndŵr,[23] died by his own hand the following year.[24] It was hard to avoid involvement with the Arundel affinity, even had Prestbury so desired. On 25 July 1407, a few days after the licence was granted for Ireland Hall, Prestbury was commissioned, along with the Earl of Arundel and two of his closest supporters, David Holbache and John Burley, to attend to the fortifications of Shrewsbury, using money from customs granted by Richard II.[25]

Chancellor of Oxford

Prestbury's career as Chancellor of the University of Oxford has been the subject of considerable revision by historians in recent years. The traditional view was that he was Chancellor in 1393–94 and 1409–10.[26] It was discovered that his activity as chancellor went on after the years 1409–10, a fact recorded by Thorold Rogers as long ago as 1904.[27] Martin Heale's 2015 biography for ODNB reflects more recent views in casting severe doubt on the first term of office while allowing for a term of almost two years from July 1409.[1] Prestbury's academic interests seem to have remained strong. During this period he was awarded a doctorate in theology by the university. He was later, in 1413, to secure two rooms in Gloucester College, Oxford for use by monks from his abbey.

Prestbury's appointment may have been in the interests of Archbishop Arundel, who was making serious efforts to suppress Lollardy. The archbishop was particularly preoccupied with cornering such reform-minded academics, Peter Payne and William Taylor.[28] He set up a committee of twelve, initially at Oxford,[29] but later extended to both universities,[30] to determine which Wycliffite teachings and writings were to be condemned and banned. A later chancellor, Thomas Gascoigne recorded that, as the commissary of the Bishop of Lincoln, Prestbury oversaw the burning of John Wycliffe's books at Carfax in the centre of Oxford, in 1410.[31] In March 1411 the committees of 12 provided Arundel with a convenient list of 267 heretical propositions,[32] which he intended to use as a check-list in a visitation of Oxford University. However, the university resisted, claiming exemption from such procedures under a papal bull of Boniface IX.[30] Prestbury published notice of Arundel's intention to carry out the visitation of the university, provoking strong resistance to what was seen as an attack on academic freedom.[1] St Mary's barred its doors against Arundel and the crisis forced the king to summon the chancellor and proctors.[33] As his position was at this time untenable, Prestbury resigned. Subsequently, the king and archbishop gained papal support for their clampdown on the university.

Conflict and pardon

The rivalry of Arundel and John Talbot, 6th Baron Furnivall led to widespread violence in Shropshire during 1413.[20] The Corbets and other Arundel supporters obstructed and then attacked the tax collectors.[22] Matters escalated to the point where the Arundel affinity mustered 2000 Chester men to attack Much Wenlock, the location of Wenlock Priory, which suffered considerable losses. The mayhem prompted the new king, Henry V, to hold the final regional sessions of the Court of King's Bench at Shrewsbury in Trinity term 1414. Although large numbers of the Arundel affinity and their opponents were indicted, the facts were disputed, the cases remanded and the accused pardoned after the magnates stood surety for them. Prestbury and his abbey were certainly allies of the Arundel faction. In February 1413 he received a general pardon from Henry IV, covering "all treasons, insurrections, rebellions, felonies, misprisions, offences, impeachments and trespasses."[34] This seems a little late for Prestbury's time at Oxford, but too early to relate to the major violence of that year, and has never been satisfactorily explained.[1] Owen and Blakeway searched in vain for any record of accusations to match the various pardons he was granted.[7] In December 1413 Prestbury was one of a group of eminent clerics commissioned to investigate and amend abuses at St Mary's Church, Shrewsbury, a royal free chapel:[35] a task that suggests he was essentially trusted by the king.

Henry V's invasion of France in 1415 took the heat out of the regional situation. The venture was not unexpected as the diplomatic prelude had been prolonged. It may explain why John Burley, a veteran lawyer of Arundel's affinity and a man well past youth,[36] decided to prolong his relationship with Shrewsbury Abbey beyond death. On 1 December 1414, working through agents who were mainly clerics, and for a fine of £20, he received a licence to alienate in mortmain to the abbey substantial holdings at Alveley on the River Severn.[37] These included two houses, agricultural land, meadow, woods, rents and a share in a weir on the river. In return the abbey promised to operate a chantry for John Burley and his wife Julian, in the chapel of St Katharine. The investment was timely. Arundel himself died of dysentery, contracted at the Siege of Harfleur, the first major engagement of the campaign. Burley followed him back to England soon afterwards and died, perhaps of the same complaint.[36]

On 28 November 1415 another pardon was issued to Prestbury.[38] This time it is known that it covered allegations of felony made by Ralph Wybynbury, a runaway monk from Shrewsbury Abbey. These were made in the County Palatine of Lancaster. Although united with the Crown since the accession of Henry IV, the palatinate had an administration and legal system distinct from the rest of England, headed by its Chancellor. The charges went back some years, into the reign of Henry IV as well as of Henry V. They were serious enough to prevent Prestbury visiting the county, which was more than inconvenient, as the abbey had considerable holdings there. However, the nature of the allegations is not made clear in the pardon. It does make clear that Prestbury was infirm by this time, as "on account of divers infirmities he is so impotent that without great bodily grievance he cannot labour for his deliverance." This may be an exaggeration but he was probably at least 70 years old by this time. Prestbury was back in royal favour fairly quickly after this second pardon.

After recording the death and burial of Glyndŵr, Adam of Usk refers to an otherwise unknown royal visit to Shrewsbury.

| Latin | English |

|---|---|

| Rex cum magna devocione ad fontem sancte Wenefrede in Northwalia et pedes a Salopia peregre proficiscitur.[39] | "The king, with great reverence, went on foot in pilgrimage from Shrewsbury to St Winifred's well in North Wales."[40] |

Apparently around 1416, this must have involved Henry V staying at Shrewsbury Abbey, which was the starting point for pilgrimages to Holywell: a mark of regard for Prestbury the abbot, if also expensive and diverting for him. It appears that the king proposed at the time to establish a chantry chapel, dedicated to St Winifred, in Shrewsbury Abbey for his own soul. However he died before this was accomplished and nothing further is heard of the project until 1463 when the Pope permitted the appropriation of Great Ness church to fund it.[41]

In 1421 further accusations were made against Prestbury. These alleged involvement in the escape of Sir John Oldcastle from the Tower of London some years earlier, on 17 October 1413.[1] Sir John had subsequently led a revolt, been captured in Herefordshire or a neighbouring part of Wales and then executed in London. As Oldcastle, a Lollard sympathiser, was convicted of heresy, the accusations against Prestbury, a known ally of the heresy-hunter Arundel, were hard to believe and nothing seems to have come of them.

Prestbury defended the abbey's interests in 1423 against the bailiffs of Shrewsbury in a dispute over the proceeds of the annual fair. However, he did not meet the abbey's obligations to contribute annually to the Benedictine provincial chapter. In 1426, just before he died, serious dissensions among the monks forced the chapter to intervene.[42] The abbot of Burton Abbey was sent in and discovered that Prestbury was apparently trying to secure the succession for a monk called William Pule, against the will of most of the convent. The prior of Worcester Cathedral was then sent in for a special visitation during July but Prestbury died around that time.

Death

Prestbury probably died in mid-July 1426. The licence to elect a successor was issued on 23 July.[43] He was succeeded not by his protégé, but by John Hampton, a monk of Shrewsbury favoured by the convent, who was confirmed by the bishop at Lilleshall parish church on 27 August.[7]

Footnotes

- Heale, Martin. "Prestbury, Thomas". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/107122. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- Morris et al. Domesday text translation, SHR 4,1,1. at Hydra Digital Repository.

- Eyton, Antiquities, volume 9, p. 28.

- Calendar of Papal Registers, Volume 2. Regesta 107: 1333-1334, 16 Kal. May.

- Letters and Papers, Henry VIII, p. 60.

- Calendar of Close Rolls, Richard II, Volume 6, p. 468, Westminster 6 April.

- Owen and Blakeway, p. 121.

- Angold, et al. Houses of Benedictine monks: The Abbey of Shrewsbury: Abbots of Shrewsbury.

- Calendar of Close Rolls, Richard II, Volume 6, p. 476, Westminster 6 April.

- Adam of Usk, p. 25-6.

- Adam of Usk, p. 175.

- Calendar of Patent Rolls, Richard II, Volume 6, p. 592, Chester, 17 August.

- Calendar of Patent Rolls, Richard II, Volume 6, p. 594.

- Owen and Blakeway, p. 32.

- Walsingham, p. 257.

- Walsingham, p. 258.

- Calendar of Patent Rolls, Henry IV, Volume 3, p. 22.

- Calendar of Patent Rolls, Henry IV, Volume 3, p. 162.

- Angold, et al. Houses of Benedictine monks: The Abbey of Shrewsbury, note anchor 170.

- Roskell, Clark and Rawcliffe. Constituencies Shropshire

- Calendar of Patent Rolls, Henry IV, Volume 3, p. 339, Westminster, 20 July 1407.

- Roskell, Clark and Rawcliffe. Members CORBET, Robert (1383-1420), of Moreton Corbet, Salop.

- Roskell, Clark and Rawcliffe. Members DARRAS, John (c.1355-1408), of Sidbury and Neenton, Salop.

- Calendar of Patent Rolls, Henry IV, Volume 3, p. 485, Westminster, 30 March 1408.

- Calendar of Patent Rolls, Henry IV, Volume 3, p. 341.

- Hibbert p. 521-1.

- Gascoigne, Rogers (ed.), p. 116, footnote 1.

- Jacob, p. 96.

- Concilia Magnae Britanniae, volume 3, p. 322-3.

- Jacob, p. 97.

- Gascoigne, Rogers (ed.), p. 116 p. 550 in original.

- Concilia Magnae Britanniae, volume 3, p. 339-49.

- Jacob, p. 98.

- Calendar of Patent Rolls, Henry IV, Volume 4, p. 464.

- Calendar of Patent Rolls, Henry V, Volume 1, p. 149.

- Roskell, Clark and Rawcliffe. Members BURLEY, John I (d.1415/16), of Broncroft in Corvedale, Salop.

- Calendar of Patent Rolls, Henry V, Volume 1, p. 258.

- Calendar of Patent Rolls, Henry V, Volume 1, p. 373.

- Adam of Usk, p. 129.

- Adam of Usk, p. 313.

- Calendar of Papal Registers, Volume 11. Vatican Regesta 491: 1463, 17 May.

- Angold, et al. Houses of Benedictine monks: The Abbey of Shrewsbury, note anchor 178.

- Calendar of Patent Rolls, Henry VI, Volume 1, p. 345.

References

- Bliss, W. H., ed. (1895). Calendar of Papal Registers Relating To Great Britain and Ireland. Vol. 2. London: HMSO. Retrieved 16 March 2016.

- Eyton, Robert William (1859). Antiquities of Shropshire. Vol. 9. London: John Russell Smith. Retrieved 15 March 2016.

- Gairdner, James, ed. (1887). Letters and Papers, Foreign and Domestic, of the Reign of Henry VIII. Vol. 10. London: HMSO. Retrieved 16 March 2016.

- Gascoigne, Thomas (1904). Rogers, James E. Thorold (ed.). Loci e Libro Veritatum: Passages Selected from Gascoigne's Theological Dictionary Illustrating the Condition of Church and State, 1403–1458 (2 ed.). Oxford: Clarendon Press. Retrieved 16 March 2016.

- Gaydon, A. T.; Pugh, R. B., eds. (1973). A History of the County of Shropshire. Vol. 2. London: British History Online. Retrieved 16 March 2016.

- Heale, Martin. "Prestbury, Thomas". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/107122. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- Hibbert, Christopher, ed. (1988). "Appendix 5: Chancellors of the University". The Encyclopaedia of Oxford. Macmillan. pp. 521–522. ISBN 0-333-39917-X.

- Jacob, E. F. (1961). "3". The Fifteenth Century. Oxford University Press. pp. 96–98. ISBN 978-0198217145.

- Maxwell Lyte, H. C., ed. (1891). Calendar of the Close Rolls, Preserved in the Public Record Office: Richard II. Vol. 6. London: HMSO. Retrieved 16 March 2016. at Brigham Young University.

- Maxwell Lyte, H. C. (ed.). Calendar of the Patent Rolls, Preserved in the Public Record Office: Richard II, 1396–1399. Vol. 6. London: HMSO. Retrieved 30 March 2016. at Iowa University

- Maxwell Lyte, H. C., ed. (1907). Calendar of the Patent Rolls, Preserved in the Public Record Office: Henry IV, 1405–1408. Vol. 3. London: HMSO. Retrieved 1 April 2016.

- Maxwell Lyte, H. C., ed. (1909). Calendar of the Patent Rolls, Preserved in the Public Record Office: Henry IV, 1408–1413. Vol. 4. London: HMSO. Retrieved 1 April 2016.

- Maxwell Lyte, H. C., ed. (1910). Calendar of the Patent Rolls, Preserved in the Public Record Office: Henry V, 1413–1416. Vol. 1. London: HMSO. Retrieved 1 April 2016.

- Maxwell Lyte, H. C., ed. (1901). Calendar of the Patent Rolls, Preserved in the Public Record Office: Henry VI, 1422–1429. Vol. 1. London: HMSO. Retrieved 1 April 2016.

- Morris, John; Palmer, J. N. N.; Palmer, Matthew; Slater, George; Caroline, Thorn; Thorn, Frank (2011). "Domesday text translation". Hydra Digital Repository. University of Hull. Retrieved 16 March 2016.

- Owen, Hugh; Blakeway, John Brickdale (1825). A History of Shrewsbury. Vol. 2. London: Harding Leppard. Retrieved 16 March 2016.

- Roskell, J. S.; Clark, L.; Rawcliffe, C., eds. (1993). History of the Parliament, 1386–1421: Constituencies. London: History of Parliament Online. Retrieved 17 March 2016.

- Roskell, J. S.; Clark, C.; Rawcliffe, L., eds. (1993). History of the Parliament, 1386–1421: Members. London: History of Parliament Online. Retrieved 17 March 2016.

- Twemlow, J. A., ed. (1921). Calendar of Papal Registers Relating To Great Britain and Ireland. Vol. 11. London: HMSO. Retrieved 16 March 2016.

- de Usk, Adam (1904). Thompson, Edward Maunde (ed.). Chronicon Adae de Usk (2 ed.). London: Henry Frowde. Retrieved 16 March 2016.

- Walsingham, Thomas (1864). Riley, Henry Thomas (ed.). Historia Anglicana. Vol. 2. London: Longman, Green. Retrieved 16 March 2016.

- Wilkins, David, ed. (1737). Concilia Magnae Britanniae et Hiberniae. Vol. 3. London: Gosling et al. Retrieved 11 August 2016.