Thomas Sumter

Thomas Sumter (August 14, 1734 – June 1, 1832) was an American military officer, planter, and politician who served in the Continental Army as a brigadier-general during the Revolutionary War. After the war, Sumter was elected to the House of Representatives and to the Senate, where he served from 1801 to 1810, when he retired. Sumter was nicknamed the "Fighting Gamecock" for his military tactics during the Revolutionary War.

Thomas Sumter | |

|---|---|

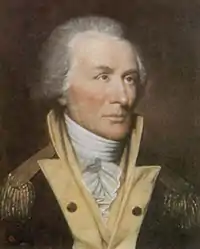

Portrait by Rembrandt Peale (c. 1795) | |

| United States Senator from South Carolina | |

| In office December 15, 1801 – December 16, 1810 | |

| Preceded by | Charles Pinckney |

| Succeeded by | John Taylor |

| Member of the U.S. House of Representatives from South Carolina's 4th district | |

| In office March 4, 1797 – December 15, 1801 | |

| Preceded by | Richard Winn |

| Succeeded by | Richard Winn |

| In office March 4, 1789 – March 3, 1793 | |

| Preceded by | Position established |

| Succeeded by | Richard Winn |

| Personal details | |

| Born | August 14, 1734 Hanover County, Virginia Colony |

| Died | June 1, 1832 (aged 97) Near Stateburg, South Carolina |

| Resting place | Thomas Sumter Memorial Park, Sumter County, South Carolina |

| Political party | Democratic-Republican Party |

| Military service | |

| Allegiance | |

| Branch/service | Virginia militia Continental Army |

| Years of service | Virginia militia (1755) Continental Army (1776–1781) |

| Rank | |

| Commands | 2nd South Carolina Regiment |

| Battles/wars | |

Early life

Thomas Sumter was born in Hanover County in the Colony of Virginia.[1] His father, William Sumpter, was a miller and former indentured servant, while his mother, Elizabeth, was a midwife. Most of Thomas Sumter's early years were spent tending livestock and helping his father at the mill, not in school.[2] Given just a rudimentary education on the frontier, the young Sumter served in the Virginia militia,[1] where he was present for Edward Braddock's defeat.[3]

The Timberlake Expedition

.jpg.webp)

At the end of the Anglo-Cherokee War, in 1761, Sumter was invited to join what was to become known as the "Timberlake Expedition", organized by Colonel Adam Stephen and led by Henry Timberlake, who had volunteered for the assignment.[4]: 38–39 The purpose of the expedition was to visit the Overhill Cherokee towns and renew alliances with the Cherokee following the war.[5] The small expeditionary party consisted of Sumter (who was partially financing the venture with borrowed money), Timberlake, an interpreter named John McCormack, and a servant.[4]: 38

According to Timberlake's journal, at one point early in the nearly year and a half long journey, Sumter swam nearly a half-mile in the icy waters to retrieve their canoe, which had drifted away while they were exploring a cave.[4]: 41–48 The party arrived in the Overhill town of Tomotley on December 20, where they were greeted by the town's head man, Ostenaco (or "Mankiller")[4]: 57–58 and soon found themselves participants in a peace pipe ceremony. In the following weeks, Sumter and the group attended peace ceremonies in several Overhill towns, such as Chota, Citico, and Chilhowee.[4]: 63–65

The party returned to Williamsburg, Virginia, accompanied by several Beloved Men of the Cherokee, arriving on the James River in early April 1762.[4]: 118–129

While in Williamsburg, Ostenaco professed a desire to meet the king of England,[4]: 130–133 and in May 1762, Sumter traveled to England with Timberlake and three distinguished Cherokee leaders, including Ostenaco. Arriving in London in early June, the Indians were an immediate attraction, drawing crowds all over the city.[6][4]: 130–136 The three Cherokee then accompanied Sumter back to America, landing in South Carolina on or about August 25, 1762.[4]: 143–147

Imprisonment for debt

Sumter became stranded in South Carolina due to financial difficulties. He petitioned the Virginia Colony for reimbursement of his travel expenses, but was denied. Subsequently, Sumter was imprisoned for debt in Virginia. When his friend and fellow soldier, Joseph Martin, arrived in Staunton, Martin asked to spend the night with Sumter in jail. Martin gave Sumter ten guineas and a tomahawk. Sumter used the money to buy his way out of jail in 1766.[7]: xxvii When Martin and Sumter were reunited some thirty years later, Sumter repaid the money.

Family life and business

Sumter settled in Stateburg, South Carolina, in the Claremont District (later the Sumter District) in the High Hills of Santee. He married Mary Jameson in 1767. Together, they opened several small businesses and eventually became members of the planter class, acquiring ownership over slave plantations.

American Revolutionary War

Sumter raised a local militia group in Stateburg. In February 1776, Sumter was elected lieutenant colonel of the Second Regiment of the South Carolina Line of which he was later appointed colonel. in 1780 he was appointed brigadier general, a post he held until the end of the war.[3] He participated in several battles in the early months of the war, including the campaign to prevent an invasion of Georgia. Perhaps his greatest military achievement was his partisan campaigning, which contributed to Lord Cornwallis' decision to abandon the Carolinas for Virginia.

During fighting in August 1780, he defeated a combined force of Loyalists and British Army regulars at Hanging Rock, and intercepted and defeated an enemy convoy. Later, however, his regiment was almost annihilated by forces led by Banastre Tarleton. He recruited a new force, defeated Major James Wemyss in November, and repulsed an attack by Tarleton, in which he was wounded.[3] Sumter was carried into the Blackstock house, where his surgeon, Dr. Nathaniel Abney, probed for and extracted the ball from under his left shoulder.

In 1781, in response to a low number of recruits, Sumter publicly implemented a bounty for Continental Army recruiters, which stipulated that anyone who managed to recruit a certain number of volunteers for the South Carolina Line would receive Loyalist-owned slaves as a reward.[8] Sumter acquired the nickname "Carolina Gamecock" during the American Revolution, for his fierce fighting tactics. After the Battle of Blackstock's Farm, British Lieutenant Colonel Banastre Tarleton commented that Sumter "fought like a gamecock", and Cornwallis described the Gamecock as his "greatest plague".[9]

Political career

After the Revolutionary War, Sumter was elected to the United States House of Representatives, serving from March 4, 1789, to March 3, 1793, and from March 4, 1797, to December 15, 1801. He later served in the United States Senate, having been selected by the legislature to fill the vacancy caused by the resignation of Senator Charles Pinckney.[1] Sumter resigned from his seat in the Senate on December 16, 1810.[1]

Family

Thomas' son, Thomas Sumter Jr., served in Rio de Janeiro from 1810 to 1819 as the United States Ambassador to the Portuguese Court during its exile to Brazil. Thomas Jr.'s wife, Natalie De Lage Sumter (née Nathalie de Lage de Volude), was a daughter of French nobility, sent by her parents to America for her safety during the French Revolution.[10] She was raised in New York City from 1794 to 1801 by Vice President Aaron Burr as his ward, alongside his own daughter Theodosia.[11][12] His grandson, Colonel Thomas De Lage Sumter, served in the U.S. Army during the Second Seminole War, and later represented South Carolina in the United States House of Representatives.[13]

Sumter's older brother, William Sumter, was a captain in the Revolutionary War.[14][15][16][17]

Death

Sumter died on June 1, 1832, at his slave plantation "South Mount", which was located near Stateburg, South Carolina, at the age of 97. Sumter was the last surviving American general of the Revolutionary War.[18] He is buried at the Thomas Sumter Memorial Park in Sumter County, South Carolina.[1]

Namesakes

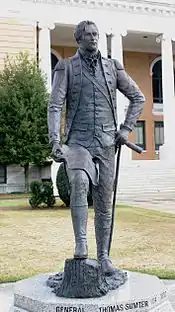

The city of Sumter, South Carolina, originally incorporated as Sumterville in 1845, was named for Thomas Sumter.[19] The city has erected a memorial to him, and has been dubbed "The Gamecock City" after his nickname.

Prior to being renamed Sumter County in 1868, Sumter District was commonly referred to as the "Old Gamecock District".[20] The use of this nickname continued after the name change, with the county thereafter being called the "Old Gamecock County".[21]

Counties in four states are named for Sumter. These are South Carolina, Florida, Alabama, and Georgia[22] The unincorporated community of Sumterville, Florida is the former seat of Sumter County, Florida. Both are named for Thomas Sumter.

Fort Sumter in Charleston Harbor, a fort planned after the War of 1812, was named in his honor. The fort is best known as the site upon which the shots initiating the American Civil War were fired, at the Battle of Fort Sumter.

Sumter's nickname, "Fighting Gamecock", has become one of several traditional nicknames for a native of South Carolina. For example, the University of South Carolina's official nickname is the "Gamecocks". Since 1903, the college's teams have been simply known as the "South Carolina Gamecocks". The costumed mascot of the University is referred to as Cocky, short for "Gamecock".

Other schools within South Carolina have been named after Sumter or utilize a Gamecock as their mascot.

- The mascot of Sumter High School is a "Gamecock" and the school's sports teams refer to themselves as the "Sumter High Gamecocks" in honor of Sumter.

- Thomas Sumter Academy, a private school within Sumter County, was founded in 1964.[23] Their mascot is known as "the General" but does not visually resemble Thomas Sumter and is typically depicted as wearing a Civil War era uniform.[23]

References

- United States Congress. "Thomas Sumter (id: S001073)". Biographical Directory of the United States Congress.

- Lockhart, Matthew A. (2016). "Sumter, Thomas". South Carolina Encyclopedia. University of South Carolina.

- Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 26 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 85.

- Timberlake, Henry (1948). Williams, Samuel (ed.). Memoirs, 1756–1765. Marietta, Georgia: Continental Book Co.

- Bass, Robert (1961). Gamecock: The Life and Campaigns of General Thomas Sumter. New York: Holt, Rinehart, and Winston. p. 9.

- St James Chronicle, July 3, 1762.

- Timberlake, Henry. King, Duane (ed.). The Memoirs of Lt. Henry Timberlake: The Story of a Soldier, Adventurer, and Emissary to the Cherokees, 1756–1765. UNC Press.

- Rees, John U. (2019). 'They Were Good Soldiers': African-Americans Serving in the Continental Army, 1775-1783. Helion & Company. ISBN 978-1-9116-2854-5.

- Buchanan, John. The Road to Guilford Courthouse. p. 393.

- Tisdale, Thomas (2001). A Lady of the High Hills: Natalie Delage Sumter. Univ. of South Carolina Press. ISBN 978-1-57003-415-2.

- Schachner, Nathan (1961) [1937]. Aaron Burr: A Biography. A. S. Barnes. Archived from the original on January 17, 2018.

- Burr, Aaron (1837). Davis, Matthew Livingston (ed.). Memoirs of Aaron Burr: With Miscellaneous Selections from His Correspondence. New York: Harper & Brothers. p. 387 n.1.

- Gilbert, Oscar E. and Catherine R.; True for the Cause of Liberty: The Second Spartan Regiment in the American Revolution; p. 194; ISBN 978-1-61200-328-3

- "General Thomas Sumter and Brother William Sumter". The Watchman and Southron. August 21, 1907. p. 2. Retrieved December 20, 2020.

- "The North Carolina Patriots – Capt. William Sumter". www.carolana.com. Retrieved December 20, 2020.

- Sumter, Joel (August 1, 1874). "Thomas Sumter Papers, Draper Manuscripts, Statement from Joel Sumter to Lyman Draper". Draper Manuscripts. 8VV344-349 [268-269]: 344–349 – via Wisconsin Historical Society.

- Kent, A.A. (April 27, 1897). "General Thomas Sumter, A Brother and Other Members of the Family that Lived in Caldwell Co, NC". Newspapers.com. The Lenoir Topic, Lenoir, North Carolina. p. 1. Retrieved January 20, 2023.

- "Thomas Sumter (U.S. National Park Service)". www.nps.gov. Retrieved December 21, 2022.

- "History & Heritage". City of Sumter, SC. August 4, 2018. Retrieved December 21, 2022.

- "Calhoun Monument Association". The Sumter Banner. Newspapers.com. March 8, 1854. Retrieved December 21, 2022.

- "The Atlanta Fair". The Watchman and Southron. Newspapers.com. August 23, 1881. Retrieved December 21, 2022.

- Krakow, Kenneth K. (1975). Georgia Place-Names: Their History and Origins (PDF). Macon, GA: Winship Press. p. 215. ISBN 0-915430-00-2.

- "History". Thomas Sumter Academy. Retrieved December 21, 2022.