The Three Marys

The Three Marys (also spelled Maries) are women mentioned in the canonical gospels' narratives of the crucifixion and resurrection of Jesus.[1][2] Mary was the most common name for Jewish women of the period.

.jpg.webp)

The Gospels refer to several women named Mary. At various points of Christian history, some of these women have been identified with one another.[3]

- Mary, mother of Jesus

- Mary Magdalene

- Mary of Jacob (mother of James the Less) (Matthew 27:56; Mark 15:40; Luke 24:10)

- Mary of Clopas (John 19:25), sometimes identified with Mary of Jacob

- Mary of Bethany (Luke 10:38–42, John 12:1–3), not mentioned in any Crucifixion or Resurrection.

Another woman who appears in the Crucifixion and Resurrection narratives is Salome, who, in some traditions, is referred to as Mary Salome and identified as being one of the Marys. Other women mentioned in the narratives are Joanna and the mother of the sons of Zebedee.

Different sets of three women have been referred to as the Three Marys:

- Three Marys present at the crucifixion of Jesus;

- Three Marys at the tomb of Jesus on Easter Sunday;

- Three daughters of Saint Anne, all named Mary.

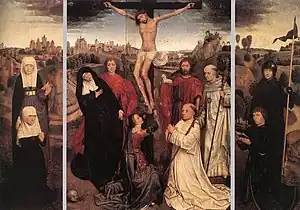

The three Marys at the crucifixion

The presence of a group of female disciples of Jesus at the crucifixion of Jesus is found in all four Gospels of the New Testament. Differences in the parallel accounts have led to different interpretations of how many and which women were present. In some traditions, as exemplified in the Irish song Caoineadh na dTrí Muire,[4] the Three Marys are the three whom the Gospel of John mentions as present at the crucifixion of Jesus:[5]

These three women are very often represented in art, as for example in El Greco's Disrobing of Christ.

The Gospels other than that of John do not mention Jesus' mother or Mary of Clopas as being present. Instead they name Mary of Jacob (Mark and Matthew), Salome (Mark), and the mother of the sons of Zebedee (Matthew).

This has led some to interpret that Mary of Jacob (mother of James the Less) is Mary Clopas and also "Mary, his mother’s sister", and that (Mary) Salome is the mother of the sons of Zebedee.

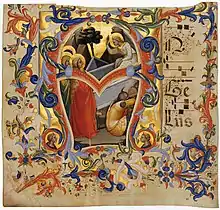

The three Marys at the tomb

.jpg.webp)

This name is used for a group of three women who came to the sepulchre of Jesus. In Eastern Orthodoxy they are among the Myrrhbearers, a group that traditionally includes a much larger number of people. All four gospels mention women going to the tomb of Jesus, but only Mark 16:1 mentions the three that this tradition interprets as bearing the name Mary:

- Mary Magdalene

- Mary of Clopas

- Mary Salome

The other gospels give various indications about the number and identity of women visiting the tomb:

- John 20:1 mentions only Mary Magdalene, but has her use the plural, saying: "We do not know where they have laid him" (John 20:2).

- Matthew 28:1 says that Mary Magdalene and "the other Mary" went to see the tomb.

- Luke 24:10 speaks of Mary Magdalene and Joanna and Mary of Jacob, and adds "the other women", after stating earlier (Luke 23:55) that at the burial of Jesus "the women who had come with him from Galilee ... saw the tomb and how his body was laid".

The Roman Martyrology commemorates Mary Magdalene on 22 July. On 24 April it commemorates "Mary of Cleopas and Salome, who, with Mary Magdalene, came very early on Easter morning to the Lord's tomb, to anoint his body, and were the first who heard the announcement of his resurrection.[6]

Women at the tomb in art

What may be the earliest known representation of three women visiting the tomb of Jesus is a fairly large fresco in the Dura-Europos church in the ancient city of Dura Europos on the Euphrates. The fresco was painted before the city's conquest and abandonment in AD 256, but it is from the 5th century that representations of either two or three women approaching a tomb guarded by an angel appear with regularity, and become the standard depiction of the Resurrection.[8] They have continued in use even after 1100, when images of the Resurrection of Jesus in Christian art began to show the risen Christ himself. Examples are the Melisende Psalter and Peter von Cornelius's The Three Marys at the Tomb. Eastern icons continue to show either the Myrrhbearers or the Harrowing of Hell.[9]

The fifteenth-century Easter hymn "O filii et filiae" refers to three women going to the tomb on Easter morning to anoint the body of Jesus. The original Latin version of the hymn identifies the women as Mary Magdalene (Maria Magdalene), Mary of Joseph (et Iacobi), and Salome (et Salome).

Legend in France

A medieval legendary account had Mary Magdalene, Mary of Jacob and Mary Salome,[10] Mark's Three Marys at the Tomb, or Mary Magdalene, Mary of Cleopas and Mary Salome,[11] with Saint Sarah, the maid of one of them, as part of a group who landed near Saintes-Maries-de-la-Mer in Provence after a voyage from the Holy Land. The group sometimes includes Lazarus, who became bishop of Aix-en-Provence, Mary of Bethany, his sister, and Joseph of Arimathea. They settled at Saintes-Maries-de-la-Mer, where their relics are a focus of the Pilgrimage to Saintes-Maries-de-la-Mer. The feast of the Three Marys was celebrated mainly in France and Italy, and was accepted by the Carmelite Order into their liturgy in 1342.[12]

The Church of the Saintes Maries de la Mer is said to hold their relics.

Processional statues during Good Friday

In various Catholic countries, particularly in the Kingdom of Spain, the Philippines and Latin American countries, images of the three Marys (in Spanish Tres Marías) associated with the tomb are carried in Good Friday processions referred to by the word Penitencia (Spanish) or Panatà (Filipino for an act performed in fulfilment of a vow).[13][14] They carry attributes or iconic accessories, chiefly enumerated as follows:

- Mary Cleopas (sometimes alternated with Mary Jacob) – holding a broom[15]

- Mary Salome – holding a thurible or censer[16]

- Mary Magdalene – holding an alabaster chalice or jar.[17]

The Blessed Virgin Mary is not part of this group, as her title as Mater Dolorosa is reserved to a singular privilege in the procession.

A common pious practice sometimes alternates Mary Salome with Jacob, due to a popular belief that Salome, an elderly person at this time would not have had the energy to reach the tomb of Christ at the morning of resurrection, though she was present at the Crucifixion.

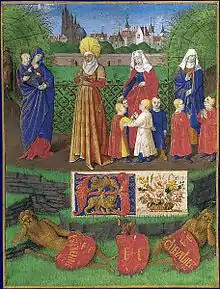

The three daughters of Saint Anne

According to a legend propounded by Haymo of Auxerre in the mid-9th century,[18] but rejected by the Council of Trent,[19] Saint Anne had, by different husbands, three daughters, all of whom bore the name Mary and who are referred to as the Three Marys:

- Mary (mother of Jesus)

- Mary of Clopas

- Salome, in this tradition called Mary Salome (as in the tradition of the three Marys at the tomb)

None of these three Marys is hypothesized as being Mary Magdalene.[20]

This account was included in the Golden Legend of Jacobus de Voragine, written in about 1260.[21]

It was the subject of a long poem in rhymed French written in about 1357 by Jean de Venette. The poem is preserved in a mid-15th-century manuscript on vellum containing 232 pages written in columns. The titles are in red and illuminated in gold. It is decorated with seven miniatures in monochrome gray.[22][23]

For some centuries, religious art throughout Germany and the Low Countries frequently presented Saint Anne with her husbands, daughters, sons-in-law and grandchildren as a group known as the Holy Kinship.

Other interpretations

The Three Marys by Alexander Moody Stuart, first published 1862, reprinted by the Banner of Truth Trust, Edinburgh, 1984, is a study of Mary of Magdala, Mary of Bethany and Mary of Nazareth.

In Spanish-speaking countries, the Orion's Belt asterism is called Las Tres Marías (The Three Marys). In other Western nations, it is sometimes called "The Three Kings", a reference to the Gospel of Matthew's account of wise men, who have been pictured as kings and as three in number, bearing gifts for the infant Jesus.[24]

See also

References

- Richard Bauckham, The Testimony of the Beloved Disciple (Baker Academic 2007 ISBN 978-0-80103485-5), p. 175

- Bart D. Ehrman, Peter, Paul, and Mary Magdalene (Osford University Press 2006 ISBN 978-0-19974113-7), p. 188

- Scott Hahn (editor), Catholic Bible Dictionary (Random House 2009 ISBN 978-0-38553008-8), pp. 583–84

- "Caoineadh na dTrí Muire" (The Lament of the Three Marys)

- John 19:25

- Martyrologium Romanum (Vatican Press 2001 ISBN 978-88-209-7210-3)

- Web Gallery of Art

- Robin Margaret Jensen, Understanding Early Christian Art (Routledge 2000 ISBN 978-0-41520454-5), p. 162

- Vladimir Lossky, 1982 The Meaning of Icons ISBN 978-0-913836-99-6 p. 185

- Hennig, Kaye D. (2008). King Arthur: Lord of the Grail. DesignMagic Publishing LLC. p. 149. ISBN 978-0-98007580-9.

- Pinckney Stetkevych, Suzanne (1994). Reorientations. Indiana University Press 1994. p. 97. ISBN 978-0-25335493-8.

- Boyce, James John (1990). "The Medieval Carmelite Office Tradition". Acta Musicologica. International Musicological Society. 62 (2/3): 133. doi:10.2307/932630. JSTOR 932630.

- Jim Yandle, "Panata by Ramos Parallels Those Final Days of Jesus" in Ocala Star Banner (6 April 1980)

- "Yolanda survivors fulfill 'panata'" in Cebu Daily News, 20 January 2014

- "Santa Maria Jacobe". 6 April 2012.

- "Santa Maria Salome -- Banga, Aklan". 11 April 2009.

- "Sta. Maria Magdalena - Viernes Santo Procession 2011". 6 July 2011.

- Patrick J. Geary, Women at the Beginning (Princeton University Press 2006 ISBN 9780691124094), p. 72

- Fernando Lanzi, Gioia Lanzi, Saints and Their Symbols (Liturgical Press 2004 ISBN 9780814629703), p. 37

- Stefano Zuffi, Gospel Figures in Art (Getty Publication 2003 ISBN 9780892367276), p. 350

- The Children and Grandchildren of Saint Anne Archived 2012-10-08 at the Wayback Machine

- "Le manuscrit médiéval" ~ The Medieval Manuscript, Nov. 2011, p. 1

- The Chronicle of Jean de Venette, translated by Jean Birdsall. Edited by Richard A. Newhall. N.Y. Columbia University Press. 1953. Introduction

- Matthew 2:1–11