Early life of Augustus

The early life of Augustus, the first Roman Emperor, began at his birth in Rome on September 23, 63 BC, and is considered to have ended around the assassination of Dictator Julius Caesar, Augustus' great-uncle and adoptive father, on 15 March 44 BC.

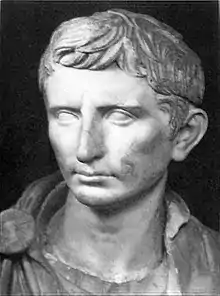

| Gaius Octavius Thurinus | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||

| Emperor of the Roman Empire | |||||

| Reign | 16 January 27 BC – 19 August AD 14 | ||||

| Successor | Tiberius, stepson by third wife, son-in-law, and adoptive son | ||||

| Born | 23 September 63 BC Velletri, Roman Republic | ||||

| Died | 19 August 14 AD Nola, Italy, Roman Empire | ||||

| Burial | |||||

| Spouse | 1) Claudia ?–40 BC 2) Scribonia 40 BC–38 BC 3) Livia Drusilla 25 BC to AD 14 | ||||

| Issue |

| ||||

| |||||

| House | Julio-Claudian | ||||

| Father | Gaius Octavius; adopted by Julius Caesar | ||||

| Mother | Atia | ||||

Childhood (63 BC – 48 BC)

.jpg.webp)

Augustus was born Gaius Octavius in Rome on 23 September 63 BC.[1] He was a member of the respectable, but undistinguished, Octavii family through his father, also named Gaius Octavius, and was the great-nephew of Julius Caesar through his mother Atia. The young Octavius had two older siblings: a half sister, Octavia Major, from his father's first marriage, and a full sister, Octavia Minor. The Octavii were wealthy through their banking business in Velletri (in the Alban Hills), where the family was part of the local aristocracy. However, the family entered into the senatorial ranks with the elder Octavius as its novus homo. The elder Octavius' entrance into the Senate came when he was appointed quaestor in 69 BC. Shortly after the younger Octavius was born, his father gained a victory at Thurii over a rebellious band of slaves, and thus the son was bestowed the cognomen "Thurinus".[1]

In 61 BC, the elder Octavius was elected praetor. Following his praetorship, he would serve for two years as governor of Macedonia.[2] There, he proved himself a capable administrator. Upon returning to Italy in 59 BC, before he could stand for the consulship, he suddenly died in Nola. This left the young Octavius, then four years old, without a father.

Octavius' mother Atia took over his education in the absence of his father. He was taught as the average Roman aristocratic boy was, learning both Latin and Greek while being trained as an orator. When Octavius was six years old Atia remarried to Lucius Marcius Philippus, a supporter of Julius Caesar and a former governor of Syria.[3] Philippus didn't care much for his new stepchildren and they were raised primarily by their grandmother Julia. He was consul of 56 BC with Gnaeus Cornelius Lentulus Marcellinus.

At this time, the First Triumvirate between Julius Caesar, Pompey the Great, and Marcus Licinius Crassus was starting to collapse. By the time Octavius was ten in 53 BC, the alliance completely broke down with the death of Crassus in Parthia. Soon thereafter, Octavius made his first public appearance in 52 BC when he delivered the funeral oration for his grandmother Julia Minor, sister of Caesar.[4] It was at this time that the young Octavius captured the attention of his great-uncle.

With Crassus dead, Caesar and Pompey began to fight each other for supremacy and power. In 50 BC, the Senate, led by Pompey, ordered Caesar to return to Rome from Gaul and to disband his army. The Senate had forbidden Caesar to stand for a second consulship in absentia. Without the consulship, Caesar would be without legal immunity and without the power of his army. Left with no other options, on 10 January 49 BC, Caesar crossed the Rubicon (the frontier boundary of Italy) with only one legion and ignited civil war.

The Senate and Pompey fled to Greece. Despite outnumbering Caesar, who only had his Thirteenth Legion with him, Pompey had no intention of fighting in Italy. Leaving Marcus Lepidus as prefect of Rome, and the rest of Italy under Mark Antony as tribune, Caesar made an astonishing 27-day route-march to Hispania, rejoining two of his Gallic legions, where he defeated Pompey's lieutenants. He then returned east, to challenge Pompey in Greece where, on 10 July 48 BC at the Battle of Dyrrhachium, Caesar barely avoided a catastrophic defeat when the line of fortification was broken. He decisively defeated Pompey, despite Pompey's numerical advantage (nearly twice the number of infantry and considerably more cavalry), at the Battle of Pharsalus in an exceedingly short engagement in 48 BC.

Family tree of the Octavii Rufi

|

Emperor |

|

Consul | ||||||||||||

| Cn. Octavius Rufus q. c. 230 BC | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Cn. Octavius pr. 205 BC | C. Octavius eq. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Cn. Octavius cos. 165 BC | C. Octavius tr. mil. 216 BC | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Cn. Octavius cos. 128 BC | M. Octavius tr. pl. 133 BC | C. Octavius magistr. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Cn. Octavius cos. 87 BC | M. Octavius tr. pl. | C. Octavius procos. MAC. 60 BC | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| L. Octavius cos. 75 BC | Cn. Octavius cos. 76 BC | C. Octavius (Augustus) imp. ROM. 27 BC–AD 14 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| M. Octavius aed. 50 BC | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Early career (48 BC – 44 BC)

The same year as Caesar’s ultimate victory against Pompey, Octavius turned 15 and donned the toga virillis on 18 October.[6] Shortly after, Octavius began his first official business upon being elected a pontiff in the College of Pontiffs.[6] It was Caesar who had nominated Octavius for this position, the first of many to come from Caesar. While it is unknown if Caesar took the time to explain the current military or political situation, he did take an interest in Octavius. While celebrating the Festival of the Latins, Caesar appointed Octavius the praefectus urbi until his return. While the position was solely honorary and possessed no authority, it allowed Octavius a place in the public eye.

From 46 BC on, Octavius was very close to Caesar and attended theatres, banquets, and other social gatherings with him. In September 46 BC, when Caesar celebrated his multiple triumphs, Octavius took part in the procession and was accorded military honors despite never having served in combat.[7] Soon, Octavius had built up considerable influence with Caesar to such a point that others would ask him to intercede with him on their behalf.

Following in the normal path of young Romans, Octavius needed experience with military affairs. Caesar proposed that Octavius join him in Africa even though Octavius had fallen ill. Though he was now legally a man, his mother Atia was still a dominating figure in his life. According to Nicolaus of Damascus, Atia protested Octavius joining Caesar, and the latter recognized the necessity of protecting Octavius’ health.[8] Though she consented for him to join Caesar in Hispania, where he planned to fight the remaining forces under Pompey’s lieutenants, but Octavius again fell ill and was unable to travel.

As soon as he was well, Octavius, accompanied by a few friends (including Marcus Vipsanius Agrippa), sailed to Hispania. He was shipwrecked and, after coming ashore with his companions, was forced to make it across hostile territory to reach Caesar's camp. Octavius’ actions greatly impressed his great-uncle, who proceeded to teach Octavius the ways of provincial administration. Suetonius in Chapter 68 of his Life of Augustus[9] writes that Lucius Antonius, the brother of Mark Antony, accused Augustus for having "given himself to Aulus Hirtius in Spain for three hundred thousand sesterces." This alleged homosexual liaison must have taken place in 46 BC during the civil wars when Julius Caesar took Octavian to Spain and Aulus Hirtius was serving there. At the time the future Emperor Augustus was 17 years old.

Caesar and Octavius stayed in Hispania until June 45 BC, after which they returned to Rome. Velleius Paterculus reports that Caesar and Octavius shared the same carriage.[10] When back in Rome, Caesar deposited a new will with the Vestal Virgins in which he secretly named Octavius as the prime beneficiary.[11] Upon returning to Rome, Caesar increasingly amassed more authority and control over the Roman state. He was made Consul for 10 years and Dictator for the same period. He was allowed to name half of the magistrates each year and even allowed to name new patricians. Among others, Caesar used this new power to elevate Octavius.

Hoping to continue Octavius’ education, at the end of 45 BC Caesar sent him, along with his friends Agrippa, Gaius Maecenas, and Quintus Salvidienus Rufus, to Apollonia in Macedonia. There, Octavius learned not only academics and self-control but military doctrine and tactics as well. Caesar, however, had more than just education in mind for Octavius. Macedonia was home of five legions and he hoped to use it as a launching ground for an upcoming war with Parthia in the Middle East.[12] In preparation, Caesar had nominated Octavius to serve as Master of the Horse (Caesar’s chief lieutenant) for the year 43 BC, thus making Octavius the number-two man in the state at the age of 19.

However, the war with the Parthians never came nor did Octavius’ promotion. While still in Apollonia, word reached Octavius that Caesar had been assassinated on the Ides of March in 44 BC. It was then made public that Caesar had adopted Octavius as his son and main heir. In response, Octavius changed his name to Gaius Julius Caesar Octavianus. Though modern scholars to avoid confusion commonly refer to him at this point as Octavian, he called himself "Caesar", which is the name his contemporaries also used. Rejecting the advice of some army officers to take refuge with his troops in Macedonia, Octavian sailed to Italy to claim his inheritance.

See also

References

- Suetonius, Augustus 5–6.

- Suetonius, Augustus 1–4.

- Suetonius, Augustus 4–8; Nicolaus of Damascus, Augustus 3.

- Suetonius, Augustus 8.1; Quintilian, 12.6.1.

- Tamsyn Barton (1995). "Augustus and Capricorn: Astrological Polyvalency and Imperial Rhetoric". The Journal of Roman Studies. Society for the Promotion of Roman Studies. 85: 47.

- Suetonius, Augustus 8.1

- Fagan, Garrett G., "Augustus (31 B.C. - 14 A.D.)", 1999

- Nicolaus of Damascus, Augustus 6.

- Suetonius, Augustus 68, translated by John Carew Rolfe.

- Velleius Paterculus 2.59.3.

- Suetonius, Julius 83 Archived 2012-05-30 at archive.today.

- Eck, 9–10