Traditional Tibetan medicine

Traditional Tibetan medicine (Tibetan: བོད་ཀྱི་གསོ་བ་རིག་པ་, Wylie: bod kyi gso ba rig pa), also known as Sowa-Rigpa medicine, is a centuries-old traditional medical system that employs a complex approach to diagnosis, incorporating techniques such as pulse analysis and urinalysis, and utilizes behavior and dietary modification, medicines composed of natural materials (e.g., herbs and minerals) and physical therapies (e.g. Tibetan acupuncture, moxabustion, etc.) to treat illness.

| This article is part of a series on |

| Alternative medicine |

|---|

|

The Tibetan medical system is based upon Indian Buddhist literature (for example Abhidharma and Vajrayana tantras) and Ayurveda.[1] It continues to be practiced in Tibet, India, Nepal, Ladakh, Siberia, and Mongolia, as well as more recently in parts of Europe and North America. It embraces the traditional Buddhist belief that all illness ultimately results from the three poisons: delusion, greed and aversion. Tibetan medicine follows the Buddha's Four Noble Truths which apply medical diagnostic logic to suffering.[2][3] The use of the caterpillar fungus (Ophiocordyceps sinensis), a world-famous medicinal and economic fungus, originates in Tibetan medicine.[4]

History

As Indian culture flooded Tibet in the eleventh and twelfth centuries, a number of Indian medical texts were also transmitted.[5] For example, the Ayurvedic Astāngahrdayasamhitā (Heart of Medicine Compendium attributed to Vagbhata) was translated into Tibetan by རིན་ཆེན་བཟང་པོ། (Rinchen Zangpo) (957–1055).[6] Tibet also absorbed the early Indian Abhidharma literature, for example the fifth-century Abhidharmakosasabhasyam by Vasubandhu, which expounds upon medical topics, such as fetal development.[7] A wide range of Indian Vajrayana tantras, containing practices based on medical anatomy, were subsequently absorbed into Tibet.[8][9]

Some scholars believe that rgyud bzhi (the Four Tantras) was told by the Buddha, while some believe it is the primary work of གཡུ་ཐོག་ཡོན་ཏན་མགོན་པོ། (Yuthok Yontan Gonpo, 708 AD).[10] The former opinion is often refuted by saying "If it was told by the Lord Buddha, rgyud bzhi should have a Sanskrit version". However, there is no such version and also no Indian practitioners who have received unbroken lineage of rgyud bzhi. Thus, the later thought should be scholarly considered authentic and practical. The provenance is uncertain.

It was the aboriginal Tibetan people's accumulative knowledge of their local plants and their various usages for benefiting people's health that were collected by སྟོན་པོ་གཤེན་རབ་མི་བོ་ཆེ། the Tonpa Shenrab Miwoche and passed down to one of his sons. Later Yuthok Yontan Gonpo perfected it and there was no author for the books, because at the time it was politically incorrect to mention anything related to Bon nor faith in it.[11]

གཡུ་ཐོག་ཡོན་ཏན་མགོན་པོ། (Yuthok Yontan Gonpo) adapted and synthesized the Four Tantras in the 12th Century. The Four Tantras are scholarly debated as having Indian origins or, as Remedy Master Buddha Bhaisajyaguru's word or, as authentically Tibetan. It was not formally taught in schools at first but, intertwined with Tibetan Buddhism. Around the turn of the 14th century, the Drangti family of physicians established a curriculum for the Four Tantras (and the supplementary literature from the Yutok school) at ས་སྐྱ་དགོན། (Sakya Monastery).[12] The ཏཱ་ལའི་བླ་མ་སྐུ་ཕྲེང་ལྔ་བ། (5th Dalai Lama) supported སྡེ་སྲིད་སངས་རྒྱས་རྒྱ་མཚོ། (Desi Sangye Gyatso) to found the pioneering Chagpori College of Medicine in 1696. Chagpori taught Gyamtso's Blue Beryl as well as the Four Tantras in a model that spread throughout Tibet along with the oral tradition.[2]

Four Tantras

The Four Tantras (Gyuzhi, རྒྱུད་བཞི།) is a native Tibetan text incorporating Indian, Chinese and Greco-Arab medical systems.[13] The Four Tantras is believed to have been created in the twelfth century and still today is considered the basis of Tibetan medical practise.[14] The Four Tantras is the common name for the text of the Secret Tantra Instruction on the Eight Branches, the Immortality Elixir essence. It considers a single medical doctrine from four perspectives. Sage Vidyajnana expounded their manifestation.[2] The basis of the Four Tantras is to keep the three bodily humors in balance; (wind rlung, bile mkhris pa, phlegm bad kan.)

- Root Tantra – A general outline of the principles of Tibetan medicine, it discusses the humors in the body and their imbalances and their link to illness. The Four Tantra uses visual observation to diagnose predominantly the analysis of the pulse, tongue and analysis of the urine (in modern terms known as urinalysis )

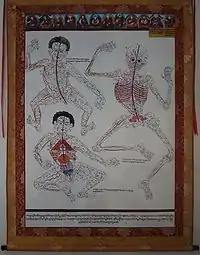

- Exegetical Tantra – This section discusses in greater detail the theory behind the Four Tantras and gives general theory on subjects such as anatomy, physiology, psychopathology, embryology and treatment.

- Instructional Tantra – The longest of the Tantras is mainly a practical application of treatment, it explains in detail illnesses and which humoral imbalance which causes the illness. This section also describes their specific treatments.

- Subsequent Tantra – Diagnosis and therapies, including the preparation of Tibetan medicine and cleansing of the body internally and externally with the use of techniques such as moxibustion, massage and minor surgeries.

Some believe the Four Tantra to be the authentic teachings of the Buddha 'Master of remedies' which was translated from Sanskrit, others believe it to be solely Tibetan in creation by Yuthog the Elder or Yuthog the Younger. Noting these two theories there remain others sceptical as to its original author.

Believers in the Buddhist origin of the Four Tantras and how it came to be in Tibet believe it was first taught in India by the Buddha when he manifested as the 'Master of Remedies'. The Four Tantra was then in the eighth century translated and offered to Padmasambhava by Vairocana and concealed in Samye monastery. In the second half of the eleventh century it was rediscovered and in the following century it was in the hands of Yuthog the Younger who completed the Four Tantras and included elements of Tibetan medicine, which would explain why there is Indian elements to the Four Tantras.[15]

Although there is clear written instruction in the Four Tantra, the oral transmission of medical knowledge still remained a strong element in Tibetan Medicine, for example oral instruction may have been needed to know how to perform a moxibustion technique.

Three principles of function

Like other systems of traditional Asian medicine, and in contrast to biomedicine, Tibetan medicine first puts forth a specific definition of health in its theoretical texts. To have good health, Tibetan medical theory states that it is necessary to maintain balance in the body's three principles of function [often translated as humors]: rLung (pron. Loong), mKhris-pa (pron. Tree-pa) [often translated as bile], and Bad-kan (pron. Pay-gen) [often translated as phlegm].[16]

• rLung[16] is the source of the body's ability to circulate physical substances (e.g. blood), energy (e.g. nervous system impulses), and the non-physical (e.g. thoughts). In embryological development, the mind's expression of materialism is manifested as the system of rLung. There are five distinct subcategories of rLung each with specific locations and functions: Srog-'Dzin rLüng, Gyen-rGyu rLung, Khyab-Byed rLüng, Me-mNyam rLung, Thur-Sel rLüng.

• mKhris-pa[16] is characterized by the quantitative and qualitative characteristics of heat, and is the source of many functions such as thermoregulation, metabolism, liver function and discriminating intellect. In embryological development, the mind's expression of aggression is manifested as the system of mKhris-pa. There are five distinct subcategories of mKhris-pa each with specific locations and functions: 'Ju-Byed mKhris-pa, sGrub-Byed mKhris-pa, mDangs-sGyur mKhris-pa, mThong-Byed mKhris-pa, mDog-Sel mKhris-pa.

• Bad-kan[16] is characterized by the quantitative and qualitative characteristics of cold, and is the source of many functions such as aspects of digestion, the maintenance of our physical structure, joint health and mental stability. In embryological development, the mind's expression of ignorance is manifested as the system of Bad-kan. There are five distinct subcategories of Bad-kan each with specific locations and functions: rTen-Byed Bad-kan, Myag-byed Bad-kan, Myong-Byed Bad-kan, Tsim-Byed Bad-kan, 'Byor-Byed Bad-kan.

Usage

A key objective of the government of Tibet is to promote traditional Tibetan medicine among the other ethnic groups in China. Once an esoteric monastic secret, the Tibet University of Traditional Tibetan Medicine and the Qinghai University Medical School now offer courses in the practice. In addition, Tibetologists from Tibet have traveled to European countries such as Spain to lecture on the topic.

The Tibetan government-in-exile has also kept up the practise of Tibetan Medicine in India since 1961 when it re-established the Men-Tsee-Khang (the Tibetan Medical and Astrological Institute). It now has 48 branch clinics in India and Nepal.[17]

The Government of India has approved the establishment of the National Institute for Sowa-Rigpa (NISR) in Leh to provide opportunities for research and development of Sowa-Rigpa.[18]

See also

References

- Garrett, Frances (2008). Religion, Medicine and the Human Embryo in Tibet. Routledge. pp. 23–32.

- Gyamtso, Sangye. "Intro card". Tibetan Medicine Cards: Illustrations and Text from the Blue Beryl Treatise of Sangye Gyamtso (1653-1705). Pomegranate Communications. p. 32. ISBN 978-0764917615.

- Kala, C.P. (2005) Health traditions of Buddhist community and role of amchis in trans-Himalayan region of India. Current Science, 89 (8): 1331-1338.

- Lu, D. (2023). The Global Circulation of Chinese Materia Medica, 1700-1949: A Microhistory of the Caterpillar Fungus. Palgrave Macmillan. pp. 1–294.

- Garrett, Frances (2008). Religion, Medicine and the Human Embryo in Tibet. Routledge. p. 23.

- Garrett, Frances (2008). Religion, Medicine and the Human Embryo in Tibet. Routledge. p. 24.

- Garrett, Frances (2008). Religion, Medicine and the Human Embryo in Tibet. Routledge. pp. 26–27.

- Garrett, Frances (2008). Religion, Medicine and the Human Embryo in Tibet. Routledge. p. 31.

- Kala, C.P. (2002) Medicinal Plants of Indian Trans-Himalaya: Focus on Tibetan Use of Medicinal Resources. Bishen Singh Mahendra Pal Singh, Dehradun, India. 200 pp.

- Mirror of Beryl: A Historical Introduction to Tibetan Medicine Desi Sangye Gyatso, translated by Gavin Kilty, Wisdom Publications 2009. ISBN 0-86171-467-9

- Phuntsok, Thubten. "བོད་ཀྱི་ལོ་རྒྱུས་སྤྱི་དོན་པདྨ་རཱ་གའི་ལྡེ་མིག "A General History of Tibet"". HimalayaBon.

- William, McGrath (2017). "Buddhism and Medicine in Tibet: Origins, Ethics, and Tradition". UVA Library | Virgo. Retrieved 2017-08-06.

- Bynum, W.F. Dictionary of Medical Biography. London: Greenwood Press. p. 1343.

- Alphen, Jon Van. Oriental Medicine- An illustrated Guide to the Asian Arts of Healing. London: Serindia Publications. p. 114.

- Alphen, Jan Van. Oriental Medicine An Illustrated Guide to the Asian Arts of Healing. London: Serindia Publications. p. 114.

- The Basic Tantra and the Explanatory Tantra from the Secret Quintessential Instructions on the Eight Branches of the Ambrosia Essence Tantra Men-Tsee-Khang: India 2008 ISBN 81-86419-62-4

- Tibetan Medical & Astrology Institute of the Dalai Lama

- "Cabinet approves establishment of National Institute for Sowa-Rigpa in Leh". www.newsonair.com. Retrieved 2019-11-21.

- Avedon, John F. (1981-01-11). "Exploring the Mysteries of Tibetan Medicine". The New York Times.

- Lowe, Justin (1997) "The wisdom of Tibetan medicine", Earth Island Journal, 0412:2, | 9(1) ISSN 1041-0406

- Evaluation of medicinal plants as part of Tibetan medicine prospective observational study in Sikkim and Nepal. Witt CM; Berling NEJ; Rinpoche NT; Cuomo M; Willich SN | Journal of Alternative & Complementary Medicine | 2009-01-0115:1, | 59(7) | ISSN 1075-5535 |

- Analysis of Five Pharmacologically Active Compounds from the Tibetan Medicine Elsholtzia with Micellar Electrokinetic Capillary Chromatography. Chenxu Ding; Lingyun Wang; Xianen Zhao; Yulin Li; Honglun Wang; Jinmao You; Yourui Suo | Journal of Liquid Chromatography & Related Technologies | 200730:20, | 3069(15) | ISSN 1082-6076

- HPLC‐APCI‐MS Determination of Free Fatty Acids in Tibet Folk Medicine Lomatogonium rotatum with Fluorescence Detection and Mass Spectrometric Identification. Yulin Li; Xian'en Zhao; Chenxu Ding; Honglun Wang; Yourui Suo; Guichen Chen; Jinmao You | Journal of Liquid Chromatography & Related Technologies | 200629:18, | 2741(11) | ISSN 1082-6076

- Stack, Peter. "The Spiritual Logic Of Tibetan Healing.(Review)." San Francisco Chronicle. (Feb 20, 1998)

- Dunkenberger, Thomas / "Tibetan Healing Handbook" / Lotus Press - Shangri-La, Twin Lakes, WI / 2000 / ISBN 0-914955-66-7

- Buddhism, science, and market: the globalisation of Tibetan medicine. JANES, CRAIG R. | Anthropology & Medicine | 2002-129:3, | 267(23) | ISSN 1364-8470 |

- Through the Tibetan Looking Glass. Bauer, James Ladd | Journal of Alternative & Complementary Medicine | 2000-086:4, | 303(2) | ISSN 1075-5535

- "So What if There is No Immediate Explanation?" Jobst, Kim A. | Journal of Alternative & Complementary Medicine | 1998-014:4, | 355(3) | ISSN 1075-5535

External links

- The first Tibetan medicine school established in the West.

- Tibetan Medical & Astro-science Institute

- Tibetanmedicine.com

- Central Council of Tibetan Medicine

- Tibet Center Institute - official Cooperation partner of Men-Tsee-Khang for the Education in Traditional Tibetan Medicine

- Academy for Traditional Tibetan Medicine

- Tibetan medicine and astrology

- Tibetan Medicine Discussion Forum