Tilted plane focus

Tilted plane photography is a method of employing focus as a descriptive, narrative or symbolic artistic device. It is distinct from the more simple uses of selective focus which highlight or emphasise a single point in an image, create an atmospheric bokeh, or miniaturise an obliquely-viewed landscape. In this method the photographer is consciously using the camera to focus on several points in the image at once while de-focussing others, thus making conceptual connections between these points.

Limits to focus in imaging

Focus is relative to spatial depth. Selective focus in photography is usually associated with depth of field. A pinhole camera generates an image of infinite relative focus, from a point just outside the camera opening out to infinity. Lenses focus more selectively so that, for objects near the lens, the distance between lens and sensor or film is increased and is shortened for more distant objects, to a point beyond which all is in focus. In telephoto lenses this point may be tens or hundreds of metres from the camera. Wide-angle lenses distinguish differences in depth only up to a short distance, beyond which all is in focus.

Depth of field

Depth of field is an effect that permits bringing objects into focus at varying distances from the camera, and at varying depth between each other, into the field of view. A short lens, as explained above, will bring objects into focus that are relatively close to the camera, but it will also keep focus at greater distances between objects. A telephoto lens will be very shallow in its gamut of focus.

Reducing the size of the aperture of the lens deepens the focus. At a pinhole size this will increase in effect, though the closer the objects are to the camera, the shorter the distance between focussed objects.

Plane of focus

Because focus depends on the distance between lens and the sensor or film plane, focus in the space in front of the camera is not on a point but rather on a plane parallel to the film plane.[1] Spherical construction of lenses, rather than the ideal parabolic construction which is rarely and expensively achieved, means that this plane is slightly concave—more so in simple single element lenses and increasingly so with lenses of lower quality construction and materials. Compound lenses are built to correct this "spherical aberration" or "curvature of field".

Tilting the plane of focus

Varying the distance between the lens and sensor or film plane across the field of view permits focussing on objects at varying distances from the camera. One means of achieving this is to tilt the lens and/or the sensor or film plane in relation to each other. This will mean that individual points in the picture plane will focus on different points of depth, with the effect that the plane of sharp focus will tilt.

This technique is based on the principle of Scheimpflug which, traditionally, is combined with small aperture to increase the gamut of focus beyond that achievable by depth of field alone. Usually no out-of-focus artifacts are desired in the image resulting from Scheimpflug adjustments. Here the converse is true. With the lens at full aperture, the photographer selects points in depth in the scene on which to focus and throws other points out-of-focus. This increases the contrast between the sharp and blurred areas and the selected application of focus and blur remains apparent to the viewer.

Tilted plane focus on smaller formats

A view camera permits full, incrementally calibrated control over this technique, though it is possible to achieve with other cameras and formats. It is possible to achieve similar effects on a 35mm camera or digital single-lens reflex camera (DSLR) using a special tilt-shift lens, or by manually holding a lens that is removed from its mount.

History

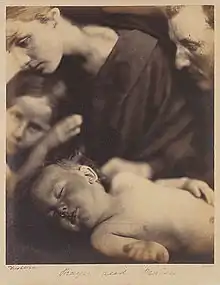

Julia Margaret Cameron was a strong advocate of this use of selective focus. For example, in "Prayer and Praise", produced in 1865, there is a deliberate placement of focus at more than three points: on the face and parts of the body of the foreground child; and faces of mother and father; while a second child's face is thrown radically out of focus.[N 1]

References

Notes

- "Moreover, effects of photographic focus are very much at play in Prayer and Praise, and they help to mount a phenomenological proof of the truth of the enacted scene. It is in the flesh of the baby, pressed to the photograph's surface, that the range from out-offocus to in-sharp-focus is most insistently displayed: note the hands and blurred upper line of the torso in contrast to the neck and underarm creases, the child's rounded facial features, somehow both blurred and distinct, and the punctal effect of the bit of hair. Thus the child's body serves to embody the photographic action of bringing into being, as well as the optical properties of the lens-and thereby serves simultaneously to embody the incorporeal means of the photograph and its own fleshy, somatic corporeality, as well as the oscillation between the two. The qualities of focus also serve to enhance another property of the medium: that of light, and the contrast between light and dark. Again that contrast is condensed in the corporeality/incorporeality of the child's body, and in the meeting between mother and child: her dark drapery and light hand, and his light body."[2]

Citations

- Faris-Belt, A. "The Elements of Photography: Understanding and Creating Sophisticated Images". Focal Press, 2008. ISBN 0-240-80942-4, ISBN 978-0-240-80942-7 extract

- Armstrong, 'C. Cupid's Pencil of Light: Julia Margaret Cameron and the Maternalization of Photography'. In "October", Vol. 76 (Spring, 1996), pp. 114–141. The MIT Press

Bibliography

- Robin Gower (1991) Professional Photography, Australia, October, p. 15

- Greg Neville (1990) 'A World of Fragments and Isolated Parts', The Age Melbourne, 9 August 1990, p. 14

- Glenda Thompson (1990) 'The Bulletin/Mumm Cordon Rouge Champagne Photographic Awards', The Bulletin, Sydney, 6 November, p. 94-98