Toms River

The Toms River is a 41.7-mile-long (67.1 km)[1] freshwater river and estuary in Ocean County, New Jersey in the United States.

| Toms River Goose Neck Creek, Goose Creek, Toms Creek | |

|---|---|

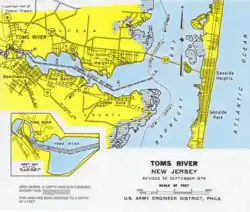

Toms River Project, US Army Corps of Engineers, 1979 | |

| |

| Location | |

| Country | United States |

| State | New Jersey |

| Municipality | Toms River, New Jersey |

| Physical characteristics | |

| Source | |

| • location | Millstone Township, New Jersey |

| • coordinates | 40.19746°N 74.41973°W |

| • elevation | 226 feet (69 m) |

| Mouth | |

• location | Toms River, New Jersey |

• coordinates | 39.93880°N 74.11201°W |

• elevation | 0 feet (0 m) |

| Width | |

| • maximum | 1.08 miles (1.74 km) at mouth |

| Discharge | |

| • location | 39.987°N 74.223°W |

| • average | 191 cubic feet per second (5.4 m3/s) |

| • minimum | 37 cubic feet per second (1.0 m3/s) |

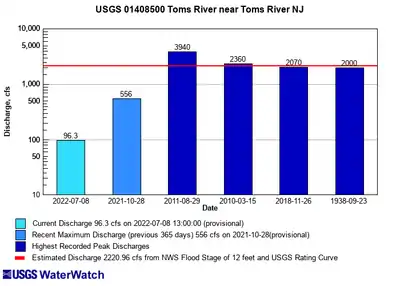

| • maximum | 3,940 cubic feet per second (112 m3/s) |

| Basin features | |

| Cities | Millstone Township, Freehold Township, Jackson Township, Manchester Township, Berkeley Township, Toms River, South Toms River, Beachwood, Pine Beach, Island Heights, Ocean Gate |

| Waterbodies | Lake Hohenstein, Barnegat Bay |

The Toms River rises in the Pine Barrens of northern Ocean County and flows southeast and east, fed by several branches, in a meandering course through area wetlands, emptying into Barnegat Bay, an inlet of the Atlantic Ocean, and the Intracoastal Waterway at Mile 14.6.[2]

Geography

Much of the headwaters of the Toms River is in the New Jersey Pine Barrens. The lower 5 miles (8.0 km) of the river is a broad tidal estuary navigable within the community of Toms River. It empties into the west side of Barnegat Bay, with mid-channel depths of 3.5 to 5 feet (1.1 to 1.5 m).[3]

At 124 sq mi (320 km2), the Toms River subwatershed is the largest drainage area of any river in the Barnegat Bay watershed.[4] It includes 11 municipalities in Ocean County, along with portions of southwestern Monmouth County.

The lowest reaches of the river provide convenient locations for marinas and yacht clubs, and points from which to go fishing and crabbing. Canoeing and kayaking are also popular on the Toms River. The river can be paddled for 21.7 miles (34.9 km) from Don Connor Boulevard, below County Route 528, all the way to Barnegat Bay.[5]

The Toms River is a tidal river.

History

Though not always named, the river has appeared on maps in the region since the New Netherland colony. Once the waterway showed up in writing, as early as 1687[6] and into the late 1700s,[7] it was most often referred to as Goose Creek or Goose Neck Creek. Cartographers bounced between Goose Creek (see: Thomas Jefferys' 1776 Map and Arrowsmith's 1804 Map) or Toms Creek (see: Mathew Carey's 1795 Map). One pair of cartographers, Henry Charles Carey and Isaac Lea, let the person reading the map decide which to call it, opting for "Goose or Toms Cr." (see: Carey's 1814 State Map of New Jersey).[8][9]

Carey and Lea would publish another map in 1822 that dropped Goose Creek's name from the river entirely.[10] Subsequent maps would follow suit with the name Toms River.[11]

Etymology

The exact origin of the name Toms River has been lost to history, but there are a number of theories. Two of the three most often referenced theories are written in historical author Edwin Salter's book A History of Monmouth and Ocean Counties: Embracing a Genealogical Record of Earliest Settlers in Monmouth and Ocean Counties and Their Descendants, from 1890. In it, Salter lays out the following sources for the river's namesake:

- Captain William Tom, an English civil officer for West Jersey from 1664 to 1674, who, during an exploratory expedition, visited the stream and the surrounding region. The name of the river was given in his honor "because he first brought it to the notice of the whites" and persuaded them to settle there.

Salter, the author of this explanation, admits that the evidence to support it is inconclusive, but still favors this one above all others, as he had previously detailed the captain's exploits in his 1874 book, Old Times in Old Monmouth. Historical Reminiscences of Old Monmouth County New Jersey

- A noted Native American, called either "Indian Tom" or "Thomas Pumha", who lived on the north bank, in what is present-day Island Heights, who assisted during the American Revolutionary War. Salter is not convinced of this theory, however, as he writes:[12]

A map or sketch made in 1740 of Mosquito Cove and mouth of Toms River (probably by Surveyor Lawrence), has marked on it "Barnegatt [sic] Tom's Wigwam," located upon north point of Mosquito Cove. (This map is in possession of S. H. Shreve, Esq., Toms River.) Indian Tom, it is stated on seemingly good authority, resided on Dillon's Island, near the mouth of Toms River, during the Revolution. As the name ."Toms River," is found about fifty years before (1727,) it throws some doubt upon the statement that the name was derived from him.

— Edwin Salter, A History of Monmouth and Ocean Counties... (1890), pp. 125-126

- Local farmer and ferryman Thomas Luker, who came to the area in the late 1600s.[13] Luker married the daughter of a local Lenape chief in 1695. Together they established a homestead on the north bend, where the river begins to open, near the site of the downtown Toms River Post Office (Water Street & Irons Street).

In 1992, for the town's 225th anniversary, Thomas Luker was officially recognized as the "Tom" in question by the township government and local historians.[14][15]

Superfund sites

Background

Beginning in the first half of the 1900s, the Ciba-Geigy Chemical Corporation established a site in Dover Township (now Toms River Township) where it manufactured pigments and dyes. The manufacturing process created a large amount of sludge and toxic waste, which was initially disposed of in unlined pits located on-site. In the 1960s, the company built a ten-mile long pipeline to disposing of nearly two billion gallons of wastewater into the Atlantic Ocean.[16]

The New Jersey Department of Environmental Protection (NJDEP) issued an Order in 1980 requiring the removal of approximately 15,000 drums from an on-site landfill, and to initiate groundwater monitoring throughout the 1,400 acres (5.7 km2) of property, which included portions of the Pine Barrens and coastal wetlands. That same year, the United States Environmental Protection Agency completed a preliminary assessment under the Potential Hazardous Waste Site Program. In 1983, the EPA placed the site on the Superfund National Priorities List.[17]

Site clean-up

The EPA has been progressing through a multi-phase cleanup of the site since the early 1980s. In September 2000, the agency order the excavation and bioremediation of about 150,000 cu yd (110,000 m3) of contaminated soil. Cleanup of the on-site source areas began in October 2003, with off-site processing and treatment finishing in 2010.[18]

According to the department's website, the following milestones have been met so far:[19]

| Milestone | Date(s) |

|---|---|

| Initial Assessment Completed | 01/01/1980 |

| Proposed to the National Priorities List | 12/30/1982 |

| Finalized on the National Priorities List | 09/08/1983 |

| Remedial Investigation Started | 03/30/1984 |

| Remedy Selected | 04/24/1989 |

| Remedial Action Started | 09/14/1989 |

| Final Remedy Selected | 09/29/2000 |

| Final Remedial Action Started | 09/30/2003 |

| Construction Completed | 09/26/2012 |

| Most Recent Five-Year Review | 05/07/2018 |

| Deleted from National Priorities List | Not Yet Achieved |

| Achieved Sitewide Ready for Anticipated Reuse | Not Yet Achieved |

The site was ordered by the EPA to undergo five reviews, each to be performed every five years. The first sitewide review was performed in September 2003. The final review is estimated to be completed in July 2023.[20]

Reich Farm

In August 1971, the Reich family leased a large portion of their 3-acre farm off Route 9 to independent waste hauler Nicholas Fernicola. The lease was to allow Fernicola to temporarily store used 55-gallon drums on the property, located approximately 1,000 ft (300 m) from an intermittent stream draining into the Toms River.

In December of that same year, the Reichs discovered nearly 4,500 waste-filled drums from Union Carbide's Bound Brook, New Jersey, plant. The family was able to identify the source of the waste by the labels left on many of the drums; the labels also indicated the contents, which included "blend of resin and oil", "tar pitch", and "lab waste solvent". Evidence of the waste being dumped was also found on the property, in the form of trenches that hadn't existed before the land was rented, as were examples of the full drums leaching their contents into the soil and nearby water table.[21][22]

The Reichs sued Fernicola and Union Carbide, and, in 1972, the court ordered an end to the dumping and the removal of all drums and contaminated soil. Despite clean-up efforts, in early 1974, residents commented on an unusual smell and taste of their well water. The NJEPA inspected the site and found the groundwater was heavily contaminated with organic compounds, such as phenol and toluene.[23]

The Reich Farm site was officially included on the EPA's National Priorities List (NPL) in September 1983.[24] After over two decades of remediation and testing, it was removed from the Superfund list in June 2021.[25] The site was ordered to undergo five reviews to be performed every five years by the EPA. The first sitewide review was performed in September 2003. The final review is estimated to be completed between September–November 2023.[26]

Cancer cluster

Both the Ciba-Geigy and Reich Farms sites resulted in the contamination of an overlapping area groundwater, during an coinciding period of time. In September 1997, the New Jersey Department of Health (NJDOH), at the request of the Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry, evaluated childhood cancer incidences in Toms River. The NJDOH reviewed data from the State Cancer Registry (SCR) from 1979 to 1991. According to the Summary Report released by the NJDOH, "The results of the 1995 NJDHSS cancer evaluation indicated that Ocean County as a whole and the Toms River section of Dover ... had an excess of childhood brain and central nervous system (CNS) cancer relative to the entire State."[27] The NJDOH reviewed the entire county, but found Toms River (then known as Dover Township) was "the only statistically significantly elevated town in the county."[27]

As a result of the findings, the NJDOH ordered a case-control study of the area to exam and identify risks factors. The results of this study were made available in January 2003, with the primary hypothesis being the cancer rates were related to the "environmental exposure pathways" reported over the previous 30 years.[28] The study reported: "No consistent patterns of association were seen between the environmental factors of primary interest and any of the cancer groupings during the postnatal exposure period" and "No consistent patterns of association were seen between the other environmental factors and any of the cancer groupings evaluated."[29] The report acknowledged the findings could be easily skewed, due to the small sample size, and recommended the continuation of clean-up efforts at the Reich Farm and Ciba-Geigy sites. It was also recommended that an additional five-year incidence evaluation be made once the data from 1996 to 2000 was available from the SCR.[30]

A 2014 Pulitzer Prize-winning book, Toms River: A Story of Science and Salvation, examined the issue of cancer clusters in detail.[31] Recent public-private coalitions to restore the river and to preserve the wetland areas near its source in the Pinelands, as well as the EPA stage assessments have resulted in an increase in water quality.[32][33]

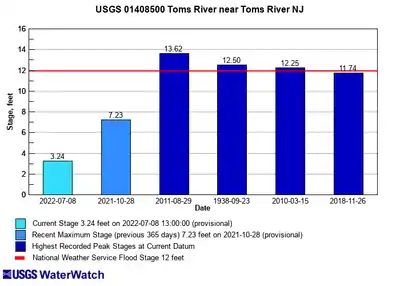

Flood events

Because the Toms River is a tidal river, with direct feed into Barnegat Bay, it is prone to flooding. The United States Geological Survey (USGS) tracks and reports on significant flood events, along with the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) tracking daily tide levels.[34]

2010 Nor'easter

From March 12–15, 2010, a Nor'easter hit the New Jersey coastline. The Toms River USGS station (01408500) recorded its highest water level since 1929 (records were not tracked prior to then),[35] and a record discharge of 2,360 cubic feet (67 m3) per second on March 15; the predicted discharge prior to the storm was only 300 cubic feet (8.5 m3) per second.[36]

Hurricane Irene

On August 28, 2011, Hurricane Irene hit the eastern coast of the US for a second time, making landfall near the Little Egg Inlet, about 25 miles (40 km) south of the river's mouth. Irene became the first hurricane to make landfall in New Jersey since 1903.[37] The storm surge that followed, combined with the rainfall from the hurricane and the wet conditions in the weeks prior, led to record USGS gage readings for over 40% of all stations with at least 20 years of data. The highest recorded flood crest of the Toms River was recorded on August 29, 2011, at 13.62 ft (4.15 m). The previous record was 12.5 ft (3.8 m), set on September 23, after the 1938 New England hurricane.[38]

The river also saw significant flow rates and gage heights in November 2018, October 2005, and May 1984.[39]

Peak streamflow through the Toms River (July 2022, USGS Water Watch)[40]

Peak streamflow through the Toms River (July 2022, USGS Water Watch)[40] Highest recorded staging of the Toms River (July 2022, USGS Water Watch)

Highest recorded staging of the Toms River (July 2022, USGS Water Watch)

Tributaries

- Davenport Branch

- Ridgeway Branch

- Union Branch

- Wrangle Brook[41]

References

- "The National Map - Advanced Viewer". apps.nationalmap.gov. Archived from the original on 2021-02-02. Retrieved 2022-06-24.

- "5". United States Coast Pilot (PDF). 3 (56th ed.). National Ocean Service, NOAA (published July 23, 2023). 2023. p. 196.

- "Toms River, NJ Weather, Tides, and Visitor Guide". US Harbors. 2019-04-04. Archived from the original on 2022-07-12. Retrieved 2022-06-24.

- "Toms River Watershed". Barnegat Bay Partnership. Archived from the original on 2022-03-24. Retrieved 2022-06-24.

- Gertler, p.127.

- Nelson, William (1899). "Documents Relating to the Colonial, Revolutionary and Post-Revolutionary History of the State of New Jersey". Archived from the original on 2022-07-22. Retrieved 2022-06-25.

- "Pensylvania, Nova Jersey et Nova York cum regionibus ad Fluvium Delaware in America sitis". Library of Congress, Washington, D.C. 20540 USA. Archived from the original on 2022-06-25. Retrieved 2022-06-24.

- "A map of the Province of New-York, reduc'd from the large drawing of that Province, compiled from actual surveys by order of His Excellency William Tryon, Esqr., Captain General & Governor of the same, by Claude Joseph Sauthier; to which is added New-Jersey". Library of Congress, Washington, D.C. 20540 USA. Archived from the original on 2022-06-25. Retrieved 2022-06-24.

- "The Province of New Jersey, divided into East and West, commonly called the Jerseys". Library of Congress, Washington, D.C. 20540 USA. Archived from the original on 2022-06-25. Retrieved 2022-06-24.

- Carey's 1822 Geographical, Historical and Statistical State Map of New Jersey Archived 2022-06-25 at the Wayback Machine.

- "Old Historical City, County and State Maps of New Jersey". Mapgeeks. 2017-12-09. Archived from the original on 2022-06-25. Retrieved 2022-06-24.

- Salter, Edwin (1890). A History of Monmouth and Ocean Counties: Embracing a Genealogical Record of Earliest Settlers in Monmouth and Ocean Counties and Their Descendants. The Indians: Their Language, Manners, and Customs. Important Historical Events... E. Gardner & Son. Archived from the original on 2022-07-22. Retrieved 2022-06-25.

- "FamilySearch.org". ancestors.familysearch.org. Archived from the original on 2022-06-25. Retrieved 2022-06-25.

- Louis, Justin. "Here's Why Toms River Is Called Toms River". 92.7 WOBM. Archived from the original on 2020-10-25. Retrieved 2022-06-23.

- "16 May 1992, Page 2 - Asbury Park Press at Newspapers.com". Newspapers.com. Archived from the original on 2022-06-25. Retrieved 2022-06-25.

- "Ocean County Residents and Green Peace Resist Waste Dumping by Ciba-Geigy Factory, 1984. | Global Nonviolent Action Database". nvdatabase.swarthmore.edu. Archived from the original on 2021-03-03. Retrieved 2022-07-03.

- "CIBA-GEIGY CORP. Site Profile". cumulis.epa.gov. Archived from the original on 2022-07-03. Retrieved 2022-07-03.

- "CIBA-GEIGY CORP. Site Profile". cumulis.epa.gov. Archived from the original on 2022-07-03. Retrieved 2022-07-03.

- "CIBA-GEIGY CORP. Site Profile". cumulis.epa.gov. Archived from the original on 2022-07-03. Retrieved 2022-07-03.

- "CIBA-GEIGY CORP. Site Profile". cumulis.epa.gov. Archived from the original on 2022-07-03. Retrieved 2022-07-03.

- "ToxicSites". www.toxicsites.us. Archived from the original on 2022-07-22. Retrieved 2022-07-03.

- Brill, Frank (2021-05-14). "Reich Farms in Toms River, NJ is coming off the EPA Superfund list. Care to comment on the environmental remediation?". EnviroPolitics. Archived from the original on 2022-07-04. Retrieved 2022-07-03.

- "REICH FARMS Site Profile". cumulis.epa.gov. Archived from the original on 2022-07-04. Retrieved 2022-07-03.

- Muszynski, William (September 30, 1988). "Record of Decision, Reich Farm" (PDF). EPA Declaration Statement: 3–5. Archived (PDF) from the original on July 12, 2022. Retrieved July 4, 2022.

- Mikle, Amanda Oglesby and Jean. "EPA yanking Toms River Reich Farm from Superfund list; water tests planned until 2023". Asbury Park Press. Archived from the original on 2022-07-22. Retrieved 2022-07-04.

- "REICH FARMS Site Profile". cumulis.epa.gov. Archived from the original on 2022-07-04. Retrieved 2022-07-04.

- "Summary: Childhood Cancer Incidence Health Consultation" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2004-10-27. Retrieved 2022-07-04.

- New Jersey Department of Health and Senior Services (January 2003). "Case-control Study of Childhood Cancers in Dover Township (Ocean County), New Jersey" (PDF). State of New Jersey. p. 2. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2022-07-08. Retrieved 2022-07-08.

- New Jersey Department of Health and Senior Services (January 2003). "Case-control Study of Childhood Cancers in Dover Township (Ocean County), New Jersey" (PDF). State of New Jersey. pp. 18–19. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2022-07-08. Retrieved 2022-07-08.

- New Jersey Department of Health and Senior Services (January 2003). "Case-control Study of Childhood Cancers in Dover Township (Ocean County), New Jersey" (PDF). State of New Jersey. p. 20. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2022-07-08. Retrieved 2022-07-08.

- "The Pulitzer Prizes - Works". pulitzer.org. Archived from the original on 2014-12-23. Retrieved 2014-12-19.

- "2019 Water Quality Network Annual Report". Barnegat Bay Partnership. 2022-03-15. Archived from the original on 2022-06-25. Retrieved 2022-06-24.

- Mikle, Jean. "Toms River cancer cluster: Will environmental rollbacks bring back 'toxic' town?". Asbury Park Press. Archived from the original on 2022-07-22. Retrieved 2022-07-04.

- "CO-OPS Map - NOAA Tides & Currents". tidesandcurrents.noaa.gov. Archived from the original on 2022-07-17. Retrieved 2022-07-08.

- "Summary of flooding caused by the March 12-15, 2010, storm in New Jersey | U.S. Geological Survey". www.usgs.gov. Archived from the original on 2022-07-08. Retrieved 2022-07-08.

- "Toms River Hydrograph | U.S. Geological Survey". www.usgs.gov. Archived from the original on 2022-07-08. Retrieved 2022-07-08.

- "Summary of Flooding in New Jersey Caused by Hurricane Irene, August 27–30, 2011 | U.S. Geological Survey". www.usgs.gov. Archived from the original on 2022-07-07. Retrieved 2022-07-08.

- "National Weather Service Advanced Hydrologic Prediction Service". water.weather.gov. Archived from the original on 2022-07-08. Retrieved 2022-07-08.

- "USGS Surface Water for USA: Peak Streamflow". nwis.waterdata.usgs.gov. Archived from the original on 2022-07-08. Retrieved 2022-07-08.

- "USGS WaterWatch -- Streamflow conditions". waterwatch.usgs.gov. Archived from the original on 2022-07-08. Retrieved 2022-07-08.

- "Toms River Watershed". Barnegat Bay Partnership. Archived from the original on 2022-03-24. Retrieved 2022-06-25.