Tom Eastick

Sir Thomas Charles Eastick, CMG, DSO, ED, JP (3 May 1900 – 16 December 1988) was a senior Australian Army artillery officer during World War II and a post-war leader of the principal ex-service organisation in South Australia. He commanded the 2/7th Field Regiment during the First and Second Battles of El Alamein in the Western Desert campaign in North Africa in 1942, leading to his appointment as a Companion of the Distinguished Service Order. Upon return from the Middle East, he commanded the artillery of the 7th Division during the final stage of the Salamaua–Lae campaign and during the Markham, Ramu and Finisterre campaigns in New Guinea between August 1943 and April 1944. He commanded the artillery of the 9th Division in the Borneo campaign in 1945. Eastick was the military governor of the Raj of Sarawak after taking the Japanese surrender at Kuching, and the commander of the Headquarters Group of Central Command in South Australia from 1950 to 1953.

Brigadier Sir Tom Eastick CMG, DSO, ED, JP | |

|---|---|

Eastick in Sarawak in late 1945 | |

| Birth name | Thomas Charles Eastick |

| Nickname(s) | February Tom |

| Born | 3 May 1900 Hyde Park, South Australia |

| Died | 16 December 1988 (aged 88) Somerton Park, South Australia |

| Allegiance | Australia |

| Service/ | Australian Army |

| Years of service |

|

| Rank | Brigadier |

| Commands held |

|

| Battles/wars | |

| Awards | |

| Relations | Bruce Eastick (son) |

| Other work | State President of the Returned Sailors', Soldiers' and Airmen's Imperial League of Australia (the Returned & Services League from 1965), 1950–1954 and 1961–1972 |

Eastick was the state president of the Returned Sailors', Soldiers' and Airmen's Imperial League of Australia (the Returned & Services League from 1965) between 1950 and 1954 and again from 1961 to 1972. He was appointed a Companion of the Order of St Michael and St George in 1953, and knighted by Queen Elizabeth II in 1970, for his volunteer work on behalf of ex-servicemen.

Early life and career

Thomas Charles Eastick was born on 3 May 1900 at Hyde Park, South Australia, the eldest of six children of Charles William Lone Eastick, who was a plumber, and his wife Agnes Ann née Scutt. Known as Tom, Eastick attended Goodwood Public School, but his formal education ended at the age of 12 when he left school to care for his ill mother and his five younger siblings. His father was at that time struggling to support the family.[1] Despite leaving school, Tom remained active in the Boy Scout movement.[2] He worked for the hardware company Colton, Palmer and Preston Ltd., as a purchasing officer. It was during this time that he acquired managerial skills that he employed effectively in his later career.[1]

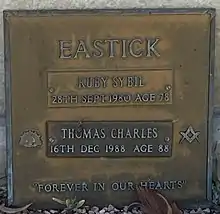

Having served four years in the compulsory senior cadets, in 1918 Eastick enlisted as a part-time soldier in the Australian Field Artillery of the Citizen Forces. He was commissioned as a lieutenant in 1922, and was posted to the 13th Field Brigade where he soon earned a reputation as an effective trainer of artillerymen. He was appointed as the commander of the 50th Battery of the four-battery brigade in 1924.[1][3] On 31 October of the following year, Eastick married Ruby Sybil Bruce, a saleswoman and youngest daughter of Mrs A. H. Bruce, in the Baptist church at Richmond, and after a honeymoon at Port Noarlunga[4] they lived in the northern part of Colonel Light Gardens known as Reade Park. The couple had five sons: Bruce, who was later the state Leader of the Opposition from 1972 to 1975 and Speaker of the South Australian House of Assembly from 1979 to 1982;[1] Keith, David, Geoff and Barry.[5]

Eastick was promoted to captain in 1926. His proficiency as an artillery officer was demonstrated by his involvement in two innovations: in 1926, he was the first Australian artillery officer to use survey procedures to accurately determine gun data to engage targets without ranging,[1] and the following year a Royal Australian Air Force pilot adjusted the fire of Eastick's battery during field firing. Also in 1927, he took over the management of an engineering company in Adelaide. This led to him co-founding a small engineering business, Angas Engineering Co. (Pty Ltd) at premises in Moore Street, Adelaide,[1][5] with a mechanic friend. The business venture went well until the Great Depression began around 1929, after which difficulties mounted.[1] In 1930, Eastick was promoted to major in the recently renamed Militia.[1][6] Eastick was appointed as a justice of the peace in 1935.[7] In 1938 his battery won the Mount Schank Trophy as the most efficient Militia field battery in the country. The following year, Eastick was temporarily promoted to lieutenant colonel and appointed as the commanding officer of the 13th Field Brigade.[1]

World War II

Service in the Middle East

In early 1940, shortly after the outbreak of World War II, Eastick put the 13th Field Brigade through a training program over a three-month period. In April his promotion to lieutenant colonel in the Militia was made substantive, and he was appointed at the same rank to raise and command the 2/7th Field Regiment, part of the Second Australian Imperial Force (Second AIF) which was being raised for overseas service.[1] Initially consisting of the 13th Battery raised in South Australia, and the 14th Battery raised in Western Australia, its original members were mainly Militia artillerymen who had volunteered for the Second AIF. In October the regiment was allocated to the 9th Division and the following month the regimental headquarters and 13th Battery embarked on the troopship SS Stratheden at Port Adelaide, and picked up the 14th Battery at Fremantle en route to the Middle East.[8][9]

Eastick's regiment arrived in the Middle East in December 1940, and was garrisoned at Qastina in Palestine where it conducted training with World War I-vintage QF 18-pounder guns and QF 4.5-inch howitzers. In March 1941 the 9th Division was moved to Egypt, but due to lack of vehicles the 2/7th Field Regiment did not join them until the following month. Initially deployed to a staging area at Ikingi Maryut,[1][8] in late May the regiment moved forward into defensive positions at Mersa Matruh.[10] By the end of July, the regiment had received most of its entitlement of 24 modern Ordnance QF 25-pounder guns.[11] In the same month, a troop of the regiment was sent to the Siwa Oasis on the edge of the Great Sand Sea. At the beginning of September, the rest of the regiment – less another troop that remained at Mersa Matruh to calibrate its newly received guns[12] – moved forward to a position between the Axis-controlled Halfaya Pass and the Allied-held fortress of Sidi Barrani.[1][8] Eastick took over the control of artillery in the coastal sector, which included anti-tank and light anti-aircraft batteries.[12] The regiment remained there, harassing the enemy, until it was relieved on 22 September.[13]

The 2/7th Field Regiment moved to reserve positions, and Eastick was briefly in command of one of the reserve columns between 26 September and 1 October.[12] In early October he was advised that his regiment was to rejoin the 9th Division,[14] which had been withdrawn from Tobruk and was rebuilding in Palestine.[1][8] As part of the withdrawal, the regiment was to be reorganised to include three batteries, the 13th, 14th and 57th.[14] The regiment remained in the desert for a while longer, harassing the enemy. On 12 October Eastick went forward to watch a troop conduct counter-battery fire in support of a raid. During the withdrawal, Eastick's vehicle was machine-gunned by German aircraft and he witnessed a British fighter pilot being shot while parachuting from his stricken aircraft. Eastick arranged a proper burial service and laid the pilot to rest where he fell. After a further successful operation coordinated with bombers against enemy camps, on 16 October the regiment drove eastwards, its fighting in the Middle East having come to an end.[15] During his time as commanding officer, Eastick became known as "February Tom", due to his proclivity to sentence disciplinary cases to 28 days' punishment.[7]

Instead of rejoining the division immediately, the 2/7th was transferred to become the depot regiment at the Royal Artillery-run Middle East School of Artillery near Cairo in Egypt for three months.[1][8] This was an honour granted in recognition of the level of efficiency reached by the regiment under Eastick's command.[1] From February to June 1942, the regiment was deployed in defensive positions at Bsarma near Tripoli in Allied-occupied French Syria.[8]

In June, the 9th Division was deployed back to Egypt to bolster Allied defences at El Alamein. The division was allocated to the northern sector and the 2/7th Field Regiment was placed under the command of the division's 26th Brigade, taking up a position at Kilo 91, east of El Alamein, on 8 July. Two days later the 26th Brigade attacked German positions on the high ground of the Tel el Eisa, supported by the whole of the divisional artillery, as part of the First Battle of El Alamein. The Germans subsequently counter-attacked, and over a five-day period, the 2/7th Field Regiment fired 20,129 rounds. In September, the regiment supported Operation Bulimba, a diversionary attack launched by the 20th Brigade.[8]

The 2/7th Field Regiment again supported the 20th Brigade during the Second Battle of El Alamein in October and November 1942, by firing 65,594 rounds across the 13 days of fighting. The regiment also participated in the pursuit of the enemy as they withdrew, pushing forward as far as El Dabaa. Following this vital success, the 9th Division, including the 2/7th Field Regiment, returned to Australia to prepare for operations against the Japanese closer to home.[8] On 15 December, Eastick was mentioned in despatches for "gallant and distinguished services in the Middle East during the period November 1941 to April 1942".[1][16] The regiment arrived in Fremantle on 18 February 1943.[8] On the same day, Eastick was made a Companion of the Distinguished Service Order in recognition of "gallant and distinguished services in the Middle East during the period May 1942 to October 1942", covering the period of both battles of El Alamein.[17] The citation stated:[18]

Lieutenant Colonel Eastick commanded his regiment with exceptional ability during difficult operations. The successful performance of tasks given to his regiment was largely due to his forcefulness and determination. He was an inspiration to his observation post officers who were always willing to act most boldly to ensure the effectiveness of the firing of the regiment. Throughout operations Colonel Eastick used his regiment aggressively and the effectiveness of its work was due largely to his leadership and personal example.

After dropping off its Western Australian members in Fremantle, the regiment disembarked in Melbourne a week later.[8] In March, Eastick was awarded the Efficiency Decoration (ED) for twenty years' service in the Citizen Forces and Militia.[5] The members of the regiment were given leave, and the regiment moved to Queensland in April for further training.[8]

Service in the Pacific

In June 1943, Eastick was appointed commander of the 7th Division artillery with the temporary rank of brigadier.[8] He deployed to New Guinea with the division in August, and commanded the artillery assets of the division during the landing at Nadzab and advance to Lae in September as part of the closing phase of the Salamaua–Lae campaign, and then during the Markham, Ramu and Finisterre campaigns until April 1944 when the division returned to Australia.[19][20] Two months later Eastick was appointed as commander of the 9th Division artillery. The 9th Division was at that time re-forming and training on the Atherton Tablelands in North Queensland after fighting in the Salamaua–Lae and Huon Peninsula campaigns in New Guinea.[21]

Due to rapid developments in the war and strategic uncertainty over the role of Australian forces in the Pacific, the 9th Division remained in Australia for over a year before seeing action once more. While the Australian I Corps (of which the 9th Division was part) had originally been intended to participate in the liberation of the Philippines, these plans were dropped, and the Corps was instead tasked with the liberation of Borneo between 1 May and 15 August 1945.[22] This was the division's final involvement in the war and its participation in the campaign was split into two primary operations: the Battle of Tarakan, a landing on Tarakan Island also known as Operation Oboe One; and Operation Oboe Six, which consisted of a landing at Brunei on the north Borneo coast, and a landing and subsequent battle on the island of Labuan.[23]

The 9th Division was responsible for administering the Japanese surrender in British Borneo, including Sarawak, Brunei and Labuan Island, and the Natuna Islands. This territory was divided into five zones, one of which was the Raj of Sarawak south of the mouth of the Rajang River. Eastick was appointed commander of Kuching Force, which was responsible for the latter zone, Kuching being the capital of the Raj of Sarawak. Kuching Force totalled around 2,000 men from the 2/4th Pioneer Battalion, 2/12th Commando Squadron, engineers from the 2/7th Field Company, and assorted other units.[24] On 6 September, Eastick flew to Kuching in a Consolidated PBY Catalina flying boat and gave instructions to Japanese officers regarding the surrender before departing. Two days later, he sailed back to Kuching aboard the Bathurst-class corvette HMAS Kapunda, and at 14:35 on 11 September he took the surrender from Major General Hiyoe Yamamura aboard Kapunda. Kuching Force disembarked that afternoon. Eastick was responsible for: accepting the surrender of the Japanese in his zone and interning them; releasing and evacuating around 2,017 Allied prisoners of war (POWs) and internees, including 400 stretcher cases and 237 women and children; and establishing military control in the zone.[25] This included liberating and repatriating Allied POWs held in the large Batu Lintang camp.[1] By 14 September, 858 POWs and internees had been evacuated.[26] By the end of October, 6,124 Japanese troops and 1,770 Japanese civilians were interned in the Kuching Force zone.[27] Eastick was military governor of Sarawak until December, when a British Indian Army garrison arrived to relieve Kuching Force.[28] Eastick then administered command of the 9th Division until February 1946, and on 28 February he transferred to the Reserve of Officers with the honorary rank of brigadier. He was subsequently made a Companion of the Order of the Star of Sarawak,[1] which he was later authorised to wear alongside his other medals.[29]

Post-war career

Eastick returned to civilian life and his business and became involved in ex-service organisations. He became a member of the Colonel Light Gardens sub-branch of the Returned Sailors', Soldiers' and Airmen's Imperial League of Australia (RSSAILA) (the Returned & Services League (RSL) from 1965), the principal Australian veterans' organisation. He was recalled to service in January 1950 with the rank of brigadier, and was posted as the commander of the Headquarters Group of Central Command in Adelaide. During this posting he was also an honorary aide-de-camp to the Governor-General of Australia, Sir William McKell. Eastick had a leading role in the development of A Call to the People of Australia,[1] an exhortation to Australian citizens to "Fear God, Honour the King", which was launched on Remembrance Day 1951 and signed by church leaders and the chief justices of the states.[30] From 1950 to 1954 he was the state president of RSSAILA,[1] and in Queen Elizabeth II's 1953 Coronation Honours was appointed a Companion of the Order of St Michael and St George (CMG) for his work with the organisation.[31] In the same year, Eastick was profiled in the Adelaide newspaper The News, which detailed some of his wide-ranging volunteer work and concluded that "he seems to have deserved that CMG".[7]

Eastick returned to the Reserve of Officers on 1 October 1953. From 1955 to 1960, Eastick was the colonel commandant of the Royal Regiment of Australian Artillery. He was again the state president of RSSAILA and then the RSL between 1961 and 1972.[1] Early in his second stint as president, Eastick urged the state premier, Sir Thomas Playford, to investigate RSSAILA allegations about communists working within state government departments.[32] Playford later tabled a report that detailed an investigation into suspected communists and commended the RSSAILA for bringing the issue to public notice.[33] Eastick was a Freemason, and the federal president of the Australia Day Council from 1963 to 1965. He served in honorary roles in about 25 organisations, many of which were ex-service related.[1]

A knighthood in recognition of his work for the interests of ex-servicemen was announced in the 1970 New Year Honours.[34] It was conferred on him in person by Queen Elizabeth II on 24 April 1970 at Government House, Canberra.[35] In September 1972, following the discovery of a National Socialist Party of Australia training camp at Gawler, South Australia, Eastick said that there was "no room in Australia for anybody with subversive thoughts like the Nazi Party".[36] In 1974, several harness races at a Globe Derby Park charity race day were named in Eastick's honour.[37] Eastick continued to work at Angas Engineering until 1977, and was again federal president of the Australia Day Council from 1976 to 1980. His wife, now Ruby, Lady Eastick, died suddenly in 1980, and after a few years he moved to the Masonic Nursing Home in Somerton Park. He died there on 16 December 1988 and was cremated.[1]

Eastick's entry in the Australian Dictionary of Biography by David N. Brook states that:[1]

Integrity, professional competence, steadfastness, self-discipline and self-reliance had been instilled in Eastick at an early age. He inspired the officers and men he commanded with his proficiency and resolution. He was a valued and trusted businessman and servant of the many organisations with which he was involved. Despite the hardships of his early life and war service, he remained a kindly and charitable man who was tough and forceful when those attributes were required. He was not flamboyant, but a consistent performer who lived by the dictum with which he had been brought up—'near enough is never good enough'.

Footnotes

- Brook 2007.

- The Daily Herald 10 April 1915.

- Palazzo 2001, p. 102.

- The Mail 5 December 1925.

- The Advertiser 16 March 1943, p. 2.

- Palazzo 2001, p. 110.

- Miles 6 June 1953.

- AWM 2021.

- Rungie 1986, pp. 92–93.

- Maughan 1966, p. 356.

- Rungie 1986, p. 94.

- Maughan 1966, p. 358.

- Maughan 1966, p. 365.

- Maughan 1966, p. 366.

- Maughan 1966, pp. 367–368.

- The London Gazette 11 December 1942.

- The London Gazette 16 February 1943.

- The News 6 May 1944, p. 3.

- Johnston 2005, pp. 172–208.

- Keogh 1965, pp. 345–359.

- Johnston 2002, p. 186.

- Keogh 1965, pp. 395–396.

- Keogh 1965, pp. 431–433.

- Long 1963, p. 561.

- Long 1963, pp. 562–563.

- Long 1963, p. 563.

- Long 1963, p. 565.

- Long 1963, p. 564.

- Commonwealth of Australia Gazette 21 November 2021.

- A Call to the People of Australia 1951.

- The London Gazette 26 May 1953.

- The Canberra Times 6 December 1962.

- Tribune 20 February 1963.

- The London Gazette 30 December 1969.

- The London Gazette 12 May 1970.

- The Australian Jewish News 8 September 1972.

- The Coromandel Times 25 April 1974.

References

Books

- Johnston, Mark (2002). That Magnificent 9th: An Illustrated History of the 9th Australian Division 1940–46. Sydney, New South Wales: Allen & Unwin. ISBN 978-1-86508-654-5.

- Johnston, Mark (2005). The Silent 7th: An Illustrated History of the 7th Australian Division 1940–46. Crows Nest, New South Wales: Allen & Unwin. ISBN 1-74114-191-5.

- Keogh, Eustace (1965). South West Pacific 1941–45. Melbourne, Victoria: Grayflower Publications. OCLC 7185705.

- Long, Gavin (1963). "Chapter 23 – After the Cease Fire". Official History of Australia in the Second World War. Australia in the War of 1939–1945. Series 1 – Army. Vol. VII – The Final Campaigns (1st ed.). Canberra, Australian Capital Territory: Australian War Memorial. pp. 548–583. OCLC 494058950.

- Maughan, Barton (1966). "Chapter 8 – Last Counter-Attack and a Controversial Relief". Official History of Australia in the Second World War. Series 1 – Army. Vol. III – Tobruk and El Alamein (1st ed.). Canberra, Australian Capital Territory: Australian War Memorial. pp. 305–383. OCLC 954993.

- Palazzo, Albert (2001). The Australian Army: A History of its Organisation 1901–2001. Melbourne, Victoria: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-551506-0.

- Rungie, R.H (1986). "2/7th Australian Field Regiment AIF". In Brook, David (ed.). Roundshot to Rapier: Artillery in South Australia 1840–1984. Hawthorndene, South Australia: Royal Artillery Association of South Australia. pp. 93–111. ISBN 0-85864-098-8.

News and documents

- "A Call to the People of Australia" (Press release). Australia: Individuals. 1951. nla.obj-2545178137. Retrieved 21 November 2021 – via National Library of Australia.

- "Ban Nazis Call in S.A." The Australian Jewish News. Vol. XXXIX, no. 1. Victoria, Australia. 8 September 1972. p. 15. Retrieved 22 November 2021.

- "Boy Scouts". The Daily Herald. Vol. 6, no. 1576. South Australia. 10 April 1915. p. 12. Retrieved 21 November 2021.

- "Eastick—Bruce". The Mail. Vol. 14, no. 706. South Australia. 5 December 1925. p. 21. Retrieved 21 November 2021.

- "Globe Derby". The Coromandel Times. Vol. 29, no. 36. South Australia. 25 April 1974. p. 4. Retrieved 21 November 2021.

- "Inquiry into Reds Promised". The Canberra Times. Vol. 37, no. 10, 401. Australian Capital Territory, Australia. 6 December 1962. p. 25. Retrieved 21 November 2021.

- "Lieut.-Col. Eastick Awarded D.S.O." The News. Vol. 42, no. 6, 480. South Australia. 6 May 1944. p. 3. Retrieved 21 November 2021.

- Miles, John (6 June 1953). "The Good Soldier". The News. Vol. 60, no. 9, 305. South Australia. p. 4. Retrieved 21 November 2021.

- "S.A. Officers Decorated". The Advertiser. Vol. LXXXV, no. 26347. South Australia. 16 March 1943. p. 2. Retrieved 21 November 2021.

- "Witch-hunters' S.A. contest". Tribune. No. 1293. New South Wales, Australia. 20 February 1963. p. 8. Retrieved 21 November 2021.

Gazettes

- "Government Gazette Appointments and Employment". Commonwealth of Australia Gazette. No. 136. Australia. 31 July 1947. p. 2203.

- "No. 35821". The London Gazette (Supplement). 11 December 1942. pp. 5437–5446.

- "No. 35908". The London Gazette (Supplement). 16 February 1943. p. 863.

- "No. 39863". The London Gazette (Supplement). 26 May 1953. p. 2944.

- "No. 44999". The London Gazette (Supplement). 30 December 1969. p. 2.

- "No. 45098". The London Gazette. 12 May 1970. p. 5343.

Websites

- "2/7th Field Regiment". Australian War Memorial. Retrieved 21 November 2021.

- Brook, David N. (2007). "Eastick, Sir Thomas Charles (Tom) (1900–1988)". Australian Dictionary of Biography. Vol. 17. National Centre of Biography, Australian National University. ISSN 1833-7538. Retrieved 20 November 2021.