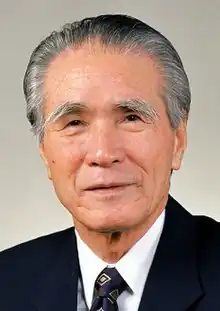

Tomiichi Murayama

Tomiichi Murayama (村山 富市, Murayama Tomiichi, born 3 March 1924) is a Japanese politician who served as Prime Minister of Japan from 1994 to 1996. He led the Japanese Socialist Party, and was responsible for changing its name to the Social Democratic Party of Japan in 1996. Upon becoming Prime Minister, he was Japan's first socialist leader in nearly fifty years. He is most remembered today for his speech "On the occasion of the 50th anniversary of the War's end", in which he publicly apologised for Japan's past colonial rule and aggression. Of the ten living former prime ministers of Japan, he is currently the oldest living prime minister, following the death of Yasuhiro Nakasone on 29 November 2019. Murayama is also the only living former Japanese prime minister who was born in the Taishō era.

Tomiichi Murayama | |

|---|---|

村山富市 | |

Official portrait, 1994 | |

| Prime Minister of Japan | |

| In office 30 June 1994 – 11 January 1996 | |

| Monarch | Akihito |

| Preceded by | Tsutomu Hata |

| Succeeded by | Ryutaro Hashimoto |

| Chairman of the Social Democratic Party | |

| In office 25 September 1993 – 28 September 1996 | |

| Preceded by | Sadao Yamahana |

| Succeeded by | Takako Doi |

| Member of the House of Representatives for Oita 1st District | |

| In office 11 December 1972 – 19 May 1980 | |

| Preceded by | Isamu Murakami |

| Succeeded by | Isamu Murakami |

| In office 19 December 1983 – 2 June 2000 | |

| Preceded by | Isamu Murakami |

| Succeeded by | Ban Kugimiya |

| Member of the Ōita Assembly for Ōita City | |

| In office 1963–1972 | |

| Member of the Ōita City Council | |

| In office 1955–1963 | |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 3 March 1924 Ōita, Empire of Japan |

| Political party | Social Democratic Party (from 1996) Socialist Party of Japan (until 1996) |

| Spouse |

Yoshie Murayama (m. 1953) |

| Alma mater | Meiji University |

| Signature | |

| Military career | |

| Allegiance | |

| Service/ | |

| Years of service | 1944–1945 |

| Rank | Officer Candidate |

| Battles/wars | Second World War |

Early life and education

Murayama was born in Ōita Prefecture on 3 March 1924; his father was a fisherman.[2][3] He entered Meiji University in 1943 as a philosophy student, but was mobilised in 1944 and assigned to work in the Ishikawajima shipyards. Later that year, he was drafted into the Imperial Army and assigned to the 72nd Infantry of the 23rd Brigade of the 23rd Division as a private second class. He was demobilised following Japan's surrender with the rank of officer candidate. Following the death of Yasuhiro Nakasone in 2019, Murayama is the only living former prime minister with military service connected to the war.

Career

Murayama was appointed secretary of the labor union in his company and entered the Japan Socialist Party, which his union supported. He began his political career as a member of the Ōita city council in 1955 and went on to serve three terms. In 1963, his supporters urged him to be a candidate for the Ōita prefectural assembly. He was elected three times successively. In 1972, he was elected to the House of Representatives of Japan.[4]

In 1991, Murayama was appointed chairman of the Diet Affairs Committee of his party. In August 1993, after the general election, the Japan Socialist Party joined the cabinet until 1994. In October of the same year, he was elected the head of the party.

Prime minister

Murayama became prime minister on 30 June 1994. The cabinet was based on a coalition consisting of the Japan Socialist Party, the Liberal Democratic Party, and the New Party Sakigake.

Because of the unwieldy coalition, his leadership was not strong. His party had been opposed to the Security Pact between Japan and the United States, but he stated that this pact was in accordance with the Constitution of Japan and disappointed many of his Socialist supporters. His government was criticised for not dealing quickly with the Great Hanshin earthquake that hit Japan on 17 January 1995.[5] Just two months later on 20 March, the Aum Shinrikyo cult carried out the Sarin gas attack on the Tokyo subway.

As the prime minister, Murayama apologised for Japan's colonial rule and aggression.[6] In social policy, various reforms were carried out in areas such as labour rights, care for the elderly,[7] child support, and assistance for people with disabilities.[8] In 1995, a law on family-care leave was introduced which made it mandatory for employers to grant a maximum of three consecutive months leave to male and female employees who need to take constant care of a family member, and prohibited employers from dismissing employees for taking family-care leave.[9] Safety standards concerning mobile cranes were established in 1995, and amendments made to the Radiation Safety Law of 1960 and the Radiation Safety Law of 1957 in 1995 extended coverage to previously excluded rental business workers, rental business offices, and rental businesses.[10] Amendments made to the Radiation Hindrance Prevention Law of 1957 in 1995 extended the law to cover rental business workers, rental business offices, and rental businesses.[11] In July 1995, a law came into effect that imposed strict liability, or liability without fault, upon manufacturers and importers of defective products.[12][13] The Food Sanitation Law of 1995 introduced a comprehensive food safety system.[14] In 1995, an amendment to the Firearm and Sword Possession Control Law made gun possession a more serious offence,[15] and the Science and Technology Basic Law passed that same year provided the framework of Japan's science and technology policy.[16]

In 1995, the Mental Health Act was revised to improve psychiatric and medical treatment and psychiatric rehabilitation "and to ensure coordination among the mental health system and other health, social service, and administrative sectors".[17] The Container and Package Recycling Law of 1995 prescribed "obligatory duties of business parties for recycling containers and packaging,"[18] while a 1995 amendment to the Mental Health Law introduced a system to provide a health and welfare handbook for people with mental disorders, and a Government Action Plan for Persons with Disabilities was launched that same year. In addition, new comprehensive employment measures were introduced.[19]

In the 1995 Japanese House of Councillors election, his party lost seats. He expressed his wish to resign from the office of prime minister, but his supporters opposed his resignation. A few months later, he resigned and was replaced by Ryutaro Hashimoto, the head of the Liberal Democratic Party.

After politics

In 2000, he retired from politics. Murayama and Mutsuko Miki traveled to North Korea in 2000 to promote better bilateral relations between the two countries.[20]

He became the president of the Asian Women's Fund, a quasi-government body that was set up to provide compensation for former comfort women.[21] After providing compensation and working on various projects, the fund was dissolved on 31 March 2007.[22]

Honours

- Grand Cordon of the Order of the Paulownia Flowers (2006)

See also

References

- "Tomiichi Murayama".

- Profile of Tomiichi Murayama

- "Japan gets first Socialist PM in 46 years". The Independent. 30 June 1994. Archived from the original on 5 November 2012. Retrieved 10 December 2010.

- "Japan's New Premier: A Sudden Arrival From the Political Margin". The Washington Post. 3 June 1994. Archived from the original on 5 November 2012. Retrieved 10 December 2010.

- "Premier faces critics over Kobe relief". Times Union. 24 January 1995. Archived from the original on 5 November 2012. Retrieved 10 December 2010.

- "Japanese PM accused of double-speak". The Independent. 16 August 1995. Retrieved 10 December 2010.

- Robert Benewick; Marc Blecher; Sarah Cook (1 March 2003). Asian Politics in Development: Essays in Honour of Gordon White. Routledge. p. 240. ISBN 978-0-203-49052-5.

- "I. General Comments". Mofa. 15 December 1995. Retrieved 24 October 2013.

- "Reforms". ISSA. Retrieved 24 October 2013.

- "Results list of Browse by country – NATLEX".

- "Results list of Browse by country – NATLEX".

- https://digital.law.washington.edu/dspace-law/bitstream/handle/1773.1/913/5PacRimLPolyJ299.pdf?sequence=1

- "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 23 May 2014. Retrieved 22 May 2014.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - Improving Efficiency and Transparency in Food Safety Systems – Sharing ... Food & Agriculture Org. 2002. ISBN 9789251047705.

- Craig Parker, L. (7 August 2001). The Japanese Police System Today. M.E. Sharpe. ISBN 9780765633750.

- Moehrle, Martin; Isenmann, Ralf; Phaal, Robert (17 January 2013). Technology Roadmapping for Strategy and Innovation. Springer. ISBN 9783642339233.

- Kim Hopper Ph, D.; Glynn Harrison, M. D.; Aleksandar Janca, M. D.; Norman Sartorius m. d., PhD (8 February 2007). Recovery from Schizophrenia: An International Perspective : A Report from ... Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780195345490.

- Imura, Hidefumi; Schreurs, Miranda Alice (January 2005). Environmental Policy in Japan. Edward Elgar. ISBN 9781781008249.

- http://www.mhlw.go.jp/english/wp/wp-hw5/dl/23020300e.pdf

- "Mutsuko Miki, activist, wife of former prime minister, dies at 95". The Asahi Shimbun. 4 August 2011. Archived from the original on 8 August 2012. Retrieved 31 July 2012.

- 8.5 million yen given to sex slave fund 2 Feb 2001 The Japan Times Retrieved 17 August 2012

- Closing of the Asian Women's Fund Asian Women's Fund Online Museum Retrieved 17 August 2012

This article incorporates text from OpenHistory.