Too Late for Tears

Too Late for Tears is a 1949 American film noir directed by Byron Haskin and starring Lizabeth Scott, Arthur Kennedy, Dan Duryea, and Don DeFore. Its plot follows a ruthless woman who resorts to perpetrating a murder spree in an attempt to retain a suitcase containing US$60,000 ($549,000 in 2021) that does not belong to her. The screenplay was written by Roy Huggins, developed from a serial he wrote for The Saturday Evening Post.

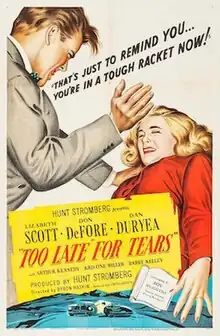

| Too Late for Tears | |

|---|---|

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Byron Haskin |

| Screenplay by | Roy Huggins |

| Based on | Too Late for Tears by Roy Huggins[1] |

| Produced by | Hunt Stromberg |

| Starring | |

| Cinematography | William C. Mellor |

| Edited by | Harry Keller |

| Music by | R. Dale Butts |

Production company | Hunt Stromberg Productions |

| Distributed by | United Artists |

Release date |

|

Running time | 100 minutes[2] |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

Originally released by United Artists in the summer of 1949, the film was reissued under the alternate title Killer Bait in 1955. It received mixed reviews from critics. The film was a box-office bomb, and its financial failure resulted in the film's producer, Hunt Stromberg, filing bankruptcy. In the years since its release, it has been noted for featuring one of Scott's strongest performances,[3] and her character one of the most vicious femme fatales in film noir.[4]

Too Late for Tears has long been in the public domain and available in varying cuts. In 2015, the UCLA Film and Television Archive and Film Noir Foundation undertook extensive restoration of the film, combining elements sourced from France with additional material from the surviving 35 mm and 16 mm prints. The restored version of the film was released in 2016 on Blu-ray by Flicker Alley in the United States, and Arrow Films in the United Kingdom. The film has developed a cult following in the years since its release.[5]

Plot

Jane and Alan Palmer are a married Los Angeles couple. Jane comes from a middle-class family and desperately longs for an upper-class lifestyle. Alan is Jane's second husband; her first killed himself when he could not meet Jane's needs. The same tensions are brewing within Jane and Alan's marriage, as Alan makes a comfortable but unexceptional salary. In the back roads of the Hollywood Hills late one night, Jane has just convinced Alan to skip out on a party hosted by a wealthy friend. As they turn the car around, a second car drives by and throws a heavy bag into the back seat. The bag is full of money. A third car chases them, but Jane drives to safety. She begs Alan to keep the money, but he assumes that it is the proceeds of a crime. To placate his wife, Alan checks the bag into Union Station while they decide whether to keep it or turn it over to the authorities.

A man named Danny Fuller appears at the Palmer apartment while Alan is at work. He makes it clear that he was the intended recipient of the money, and threatens her for it. She casually invents a series of lies to explain why she does not have it, eventually agreeing to give him half. When Alan makes it clear that he intends to turn over the money, Jane concocts a plan to get it. She arranges a date with Alan at the pleasure boating lake where they first met, and asks Danny to meet her there. On the boat, Alan finds that Jane has brought his pistol along. They struggle for the gun, a shot rings out, and Alan collapses dead in the boat. Danny hops aboard, puts on Alan's coat and hat, and helps Jane weigh down the body in the lake. Jane lies again to Danny and tells him that they money is hidden in the countryside. She takes him there in an attempt to kill him, but he sees through the ruse and leaves. Jane then leaves her car at a beach, staging it to make it seem as though Alan fled to Mexico.

Jane reports Alan missing to the police, deeply troubling Alan's sister Kathy, who lives next door. She realizes that the claim ticket for the bag is missing and assumes that Alan has it. In truth, Kathy has taken it while looking around Jane's apartment for clues to Alan's location. An amicable stranger, Don Blake, arrives looking for Alan. He claims to have served in the Air Force with Alan and resolves to find him when he hears that he has gone missing. Jane realizes that Kathy has the ticket and has become suspicious of her. She pressures Danny into buying a poison with which to quietly kill her. As Don and Kathy are about to leave for a date, Jane invites them into her apartment and proves that Don did not serve with Alan. She holds Kathy and Don at gunpoint, retrieves the ticket, and pistol-whips Don unconscious. Kathy calls the police and begs them to monitor Union Station for Jane, but they refuse, having no evidence that a crime has been committed.

Jane retrieves the bag. A drunk and depressed Danny confesses that the money is a blackmail payoff intended to keep him quiet about a large insurance scam. Jane kills him with the poison, then flees to Mexico. The police are convinced that Danny's death is a suicide, but Don is not. He tracks Jane down in a Mexican resort, where she now lives in luxury. He tricks her into thinking that he knows that Alan was murdered, coaxing a confession out of her in the form of another payoff. Don then reveals that he is the brother of her first husband and suspects that she killed him too. The Mexican police burst into the room, and Jane accidentally falls to her death. Don finds Kathy (now his wife) in the hotel lobby, and they decide to end their "honeymoon" early.

Cast

- Lizabeth Scott as Jane Palmer

- Don DeFore as Don Blake/Blanchard

- Dan Duryea as Danny Fuller

- Arthur Kennedy as Alan Palmer

- Kristine Miller as Kathy Palmer

- Barry Kelley as Lieutenant Breach

Production

Development

The film was adapted for the screen by Roy Huggins, based on his own serialized novel of the same name, which had been published by The Saturday Evening Post.[6] The film's producer, Hunt Stromberg, had a successful film career working for Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer, had left the studio and began producing independent films.[7][8]

Casting

Stromberg initially sought Joan Crawford for the lead role of Jane Palmer, Kirk Douglas as Danny Fuller, and Wendell Corey as Don Blake.[7] Instead, Hal B. Wallis, with whom Lizabeth Scott was under contract, loaned out her for the project[7] at the request of director Byron Haskin, who had previously directed Scott in I Walk Alone (1947).[5] Don DeFore and Dan Duryea were ultimately cast as Don and Danny, respectively.[7]

Release

Too Late for Tears was distributed by United Artists, opening regionally in Arkansas and Kentucky on July 3, 1949.[9][10] The film opened in Los Angeles on July 13, 1949.[2]

It was re-released in August 1955 under the alternate title Killer Bait by Astor Pictures, a distributor that specialized in theatrical reissuing of films.[11] Astor Pictures often paired the film as a double feature with Johnny Holiday (1948), which they reissued under the alternative title Boy's Prison.[11]

Box office

Too Late for Tears was a box-office bomb at the time of its release, sending its producer into bankruptcy.[3]

Critical response

Upon its original release, Too Late for Tears received mixed reviews from critics.[7] A. H. Weiler of The New York Times wrote:

If proof be needed at this point that money is the root of all evil—a theme, incidentally, which has been the root of more than one motion picture—then Too Late for Tears, which came to the Mayfair on Saturday, is proof positive. For producer Hunt Stromberg, director Byron Haskin and scenarist Roy Huggins, who adapted his own Saturday Evening Post serial, herein have fashioned an effective melodramatic elaboration of that theme. Despite an involved plot and an occasional overabundance of palaver, not all of which is bright, this yarn about a cash-hungry dame who doesn't let men or conscience stand in her way, is an adult and generally suspenseful adventure.[6]

Philip K. Scheuer of the Los Angeles Times conceded that Scott "gives the role everything she does have with a growling, unvarying intensity," but felt that overall the film was "a routine specimen of crime melodrama."[12] A review published by the Spokane Chronicle described the film as "dramatic and tragic" and "an action-packed film which has its good moments."[13] Alternately, a reviewer for the Detroit Free Press was unimpressed by Scott's performance, writing: "She produces a characterization which is without explanation or belief... Miss Scott appears terribly tired in the film. Her acting has the same quality. All of which leaves what should have been an exciting movie in a somewhat rundown condition."[14]

Film critic Dennis Schwartz in 2005 wrote a favorable review:

Byron Haskin's low-budget film noir makes good use of its Los Angeles locale and its lady bluebeard is fun to watch as she does her nasty gun thing with her nice guy hubby and rotten poison thing with her boyfriend (she took care of her first hubby off camera, so we're not sure how he got it!)...Though a minor film noir, it relates to the ambitions the middle-class had during the postwar period to better their life materially and socially. Jane's drive for wealth was so extreme that she will not stop at murder to rise above her impoverished middle-class circumstances, and her warped character is used to show how money can't buy one happiness. The husky-voiced winsome smiling Lizabeth Scott turns in a finely tuned performance as the femme fatale; while Dan Duryea is in his element as the alcoholic weak-kneed cad, who shows he doesn't have as much stomach for his criminal mischief as does his lady accomplice.[15]

As of May 2023, the film holds a 100% approval rating on the review aggregator Rotten Tomatoes, based on five critical reviews.[16]

Restoration

Too Late for Tears fell in the public domain in the decades after its release, owing to the dissolution of its corporate holders who failed to renew its copyright.[8] The original camera negatives were subsequently lost.[8] It has been released on VHS and DVD by numerous distribution companies.[17]

The Film Noir Foundation, dedicated to preserving film noirs, had sought to restore the film since its inception in 2006, but were unable to locate quality prints.[8] In 2011, Eddie Muller, a film scholar and president of the foundation, received anonymous correspondence regarding a 35 mm print of the film that had allegedly been sold to a collector on the East Coast.[8] Muller tracked the print to a collector in Baltimore, who claimed the print had been kept in storage, but the collector died before he was able to negotiate a sale or disclose its location.[8]

After a 35 mm print dupe negative was located in France, the UCLA Film and Television Archive and the Film Noir Foundation began undertaking the restoration process, with the Hollywood Foreign Press Association, providing additional funding.[18] The restoration entailed the use of both the French 35 mm print (bearing the French language title, Le Tigresse), as well as an American 35 mm print from 1955, when the film was re-released bearing the alternate title Killer Bait.[8] Because of this, the film's original English-language opening title had to be reconstructed via rotoscoping and matching the fonts as they appeared on an inferior 16 mm print of the film.[8][19] The film's closing titles also had to be reconstructed using the same method.[8]

On January 25, 2014, the restored 35 mm print was premiered by the Film Noir Foundation at Noir City 12 at the Castro Theatre in San Francisco. The restored print of the film was released in a DVD and Blu-ray set by Flicker Alley in May 2016.[20] The following month, British distributor Arrow Films released the restored print in a DVD and Blu-ray set through their Arrow Academy label.[21]

Legacy

Scott's performance in the film is regarded by several critics as among her best work.[3] Her femme fatale character in the film has been noted as one of the most merciless and avaricious in film noir,[4] and marked a departure from her previous performances in Pitfall (1948), which featured elements of character vulnerability.[22] Film scholar Fabio Vighi notes in Critical Theory and Film: Rethinking Ideology Through Film Noir that, "Like few other femmes, she appears unstoppable, ready to do anything to achieve her object."[23]

Interviewed in 2001, Scott commented on the role: "Obviously, there was a softness and an inordinate amount of feminine qualities in [the character]... When a woman like this is corrupted, she would surrender to that corruption. Money would become her delight and her total obsession, and she would then kill for it."[24]

Too Late for Tears has developed a cult following in the decades since its original release.[5] Todd Weiner of the UCLA Film & Television Archive wrote upon the film's 2016 Blu-ray release: "Modern audiences now recognize it as a darkly satisfying and atmospheric meditation on the covetous societal and materialistic ambitions of postwar middle-class America."[5] Film critic and writer Eddie Muller cites the film as "The best un-known American film noir of the classic era."[5]

References

- "Archived Review: Roy Huggins – Too Late for Tears". Mystery File. March 2, 2013. Archived from the original on May 30, 2023.

- "Too Late for Tears". AFI Catalog of Feature Films. American Film Institute. Retrieved May 29, 2023.

- Landau 2016, p. 75.

- Spicer 2018, p. 101.

- Weiner, Todd. "Too Late For Tears". Gartenberg Media. UCLA Film & Television Archive. Archived from the original on May 29, 2023.

- Weiler, A. H. (August 15, 1949). "The Screen In Review; 'Too Late for Tears,' Adult and Suspenseful Adventure Film, Is New Bill at Mayfair". The New York Times. Archived from the original on July 10, 2012.

- The Chance of a Lifetime: The Making of 'Too Late for Tears' (Blu-ray documentary short). Flicker Alley. 2016. OCLC 949932389.

- Tiger Hunt: Restoring 'Too Late for Tears' (Blu-ray documentary short). Flicker Alley. 2016. OCLC 949932389.

- "'Too Late for Tears' to play at Saenger". Hope Star. June 29, 1949. p. 3 – via Newspapers.com.

- "Lizabeth Scott, Dan Duryea, Don De Fore Star in 'Too Late for Tears'". The Owensboro Messenger. July 3, 1949. p. 3-B – via Newspapers.com.

- Pitts 2019, p. 30.

- Scheuer, Philip K. (July 28, 1949). "Housewife Turns 'Tiger' in 'Too Late for Tears'". Los Angeles Times. p. 21 – via Newspapers.com.

- B. F. (July 14, 1949). "Greedy Woman Theme of Film". Spokane Chronicle. p. 22 – via Newspapers.com.

- N. K. (August 12, 1949). "Lizabeth Scott Finds Murder a Tiring Task". Detroit Free Press. p. 16 – via Newspapers.com.

- Schwartz, Dennis. Ozus' World Movie Reviews, film review, February 22, 2005. Last accessed: February 15, 2011.

- "Too Late for Tears". Rotten Tomatoes. Retrieved May 29, 2023.

- "Too Late for Tears: Formats and Editions". WorldCat. Archived from the original on May 30, 2023.

- "Too Late for Tears / The Guilty". UCLA Film & Television Archive. University of California, Los Angeles. 2015. Archived from the original on April 10, 2023.

- Arnold, Jeremy. "Too Late for Tears (1949)". Turner Classic Movies. Archived from the original on May 29, 2023.

- "Too Late for Tears Blu-ray (Blu-ray + DVD)". Blu-ray.com. Archived from the original on May 29, 2023.

- "Too Late for Tears Blu-ray (Arrow Academy / Blu-ray + DVD)". Blu-ray.com. Archived from the original on May 29, 2023.

- Mayer 2012, p. 341.

- Vighi 2012, p. 72.

- Porfirio, Silver & Ursini 2001, p. 194.

Sources

- Landau, David (2016). Film Noir Production: The Whodunit of the Classic American Mystery Film. New York City, New York: Routledge. ISBN 978-1-315-51172-6.

- Mayer, Geoff (2012). The Historical Dictionary of Film Noir. Lanham, Maryland: Scarecrow Press. ISBN 978-0-810-86769-7.

- Pitts, Michael R. (2019). Astor Pictures: A Filmography and History of the Reissue King, 1933-1965. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland. ISBN 978-1-476-63628-3.

- Porfirio, Robert; Silver, Alain; Ursini, James, eds. (2001). Film Noir Reader 3: Interviews with Filmmakers of the Classic Noir Period. New York City, New York: Limelight Editions. ISBN 978-0-879-10961-5.

- Spicer, Andrew (2018). Film Noir. Inside Film. New York City, New York: Routledge. ISBN 978-1-317-87503-1.

- Vighi, Fabio (2012). Critical Theory and Film: Rethinking Ideology Through Film Noir. New York City, New York: Continuum Books. ISBN 978-1-441-13912-2.

External links

- Too Late For Tears at IMDb

- Too Late For Tears at AllMovie

- Too Late for Tears at the TCM Movie Database

- Too Late For Tears at the American Film Institute Catalog

- Too Late for Tears at Rotten Tomatoes

- Too Late for Tears is available for free viewing and download at the Internet Archive

- Too Late For Tears film on YouTube (complete)