Electric ray

The electric rays are a group of rays, flattened cartilaginous fish with enlarged pectoral fins, composing the order Torpediniformes /tɔːrˈpɛdɪnɪfɔːrmiːz/. They are known for being capable of producing an electric discharge, ranging from 8 to 220 volts, depending on species, used to stun prey and for defense.[2] There are 69 species in four families.

| Electric rays Temporal range: | |

|---|---|

| |

| Marbled electric ray (Torpedo marmorata) | |

| |

| Lesser electric ray (Narcine bancroftii) | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Chondrichthyes |

| Superorder: | Batoidea |

| Order: | Torpediniformes F. de Buen, 1926 |

| Families | |

Perhaps the best known members are those of the genus Torpedo. The torpedo undersea weapon is named after it. The name comes from the Latin torpere, 'to be stiffened or paralyzed', from the effect on someone who touches the fish.[3]

Description

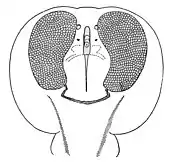

Electric rays have a rounded pectoral disc with two moderately large rounded-angular (not pointed or hooked) dorsal fins (reduced in some Narcinidae), and a stout muscular tail with a well-developed caudal fin. The body is thick and flabby, with soft loose skin with no dermal denticles or thorns. A pair of kidney-shaped electric organs are at the base of the pectoral fins. The snout is broad, large in the Narcinidae, but reduced in all other families. The mouth, nostrils, and five pairs of gill slits are underneath the disc.[2][4]

Electric rays are found from shallow coastal waters down to at least 1,000 m (3,300 ft) deep. They are sluggish and slow-moving, propelling themselves with their tails, not by using their pectoral fins as other rays do. They feed on invertebrates and small fish. They lie in wait for prey below the sand or other substrate, using their electricity to stun and capture it.[5]

Relationship to humans

History of research

The electrogenic properties of electric rays have been known since antiquity, although their nature was not understood. The ancient Greeks used electric rays to numb the pain of childbirth and operations.[2] In his dialogue Meno, Plato has the character Meno accuse Socrates of "stunning" people with his puzzling questions, in a manner similar to the way the torpedo fish stuns with electricity.[6] Scribonius Largus, a Roman physician, recorded the use of torpedo fish for treatment of headaches and gout in his Compositiones Medicae of 46 AD.[7]

In the 1770s the electric organs of the torpedo ray were the subject of Royal Society papers by John Walsh,[8] and John Hunter.[9][10] These appear to have influenced the thinking of Luigi Galvani and Alessandro Volta – the founders of electrophysiology and electrochemistry.[11][12] Henry Cavendish proposed that electric rays use electricity; he built an artificial ray consisting of fish shaped Leyden jars to successfully mimic their behaviour in 1773.[13]

In folklore

The torpedo fish, or electric ray, appears continuously in premodern natural histories as a magical creature, and its ability to numb fishermen without seeming to touch them was a significant source of evidence for the belief in occult qualities in nature during the ages before the discovery of electricity as an explanatory mode.[14]

Bioelectricity

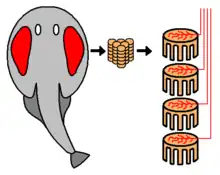

The electric rays have specialised electric organs. Many species of rays and skates outside the family have electric organs in the tail; however, the electric ray has two large kidney-shaped electric organs on each side of its head, where current passes from the lower to the upper surface of the body. The nerves that signal the organ to discharge branch repeatedly, then attach to the lower side of each plaque in the batteries.[2] These are composed of hexagonal columns, closely packed in a honeycomb formation. Each column consists of 500 to more than 1000 plaques of modified striated muscle, adapted from the branchial (gill arch) muscles.[2][15][16] In marine fish, these batteries are connected as a parallel circuit, whereas freshwater batteries are arranged in series. This allows freshwater rays to transmit discharges of higher voltage, as freshwater cannot conduct electricity as well as saltwater.[17] With such a battery, an electric ray may electrocute larger prey with a voltage of between 8 volts in some narcinids to 220 volts in Torpedo nobiliana, the Atlantic torpedo.[2][18]

Systematics

The 60 or so species of electric rays are grouped into 12 genera and two families.[19] The Narkinae are sometimes elevated to a family, the Narkidae. The torpedinids feed on large prey, which are stunned using their electric organs and swallowed whole, while the narcinids specialize on small prey on or in the bottom substrate. Both groups use electricity for defense, but it is unclear whether the narcinids use electricity in feeding.[20]

- Family Narcinidae (numbfishes)

- Subfamily Narcininae

- Genus Benthobatis

- Genus Diplobatis

- Genus Discopyge

- Genus Narcine

- Subfamily Narkinae (sleeper rays)

- Genus Crassinarke

- Genus Electrolux

- Genus Heteronarce

- Genus Narke

- Genus Temera

- Genus Typhlonarke

- Subfamily Narcininae

- Family Hypnidae (coffin rays)

- Family Torpedinidae (torpedo electric rays)

- Subfamily Torpedininae

- Genus Tetronarce

- Genus Torpedo

- Subfamily Torpedininae

See also

References

- Froese, Rainer, and Daniel Pauly, eds. (2011). "Torpediniformes" in FishBase. February 2011 version.

- Martin, R. Aidan. "Electric Rays". ReefQuest Centre for Shark Research. Archived from the original on 15 October 2008. Retrieved 12 October 2008.

- Kidd, D. A. (1973). "Torpedo". Collins Latin Gem Dictionary: Latin-English, English-Latin. ISBN 0-00-458641-7.

{{cite encyclopedia}}:|work=ignored (help) - Hamlett, William C. (1999). Sharks, Skates, and Rays: The Biology of Elasmobranch Fishes. Baltimore and London: JHU Press. ISBN 0-8018-6048-2.

- Stevens, J.; Last, P. K. (1998). Paxton, J. R.; Eschmeyer, W. N. (eds.). Encyclopedia of Fishes. San Diego: Academic Press. p. 66. ISBN 0-12-547665-5.

- Wikisource:Meno

- Theodore Holmes Bullock; Carl D. Hopkins; Richard R. Fay (28 September 2006). Electroreception. Springer Science & Business Media. p. 6. ISBN 978-0-387-28275-6.

- Walsh, John (1773). "On the Electric Property of the Torpedo: in a Letter to Benjamin Franklin". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London (64): 461–480.

- Hunter, John (1773). "Anatomical Observations on the Torpedo. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London" (63): 481–489.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - Hunter, John (1775). "An account of the Gymnotus electricus". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London (65): 395–407.

- Alexander, Mauro (1969). "The role of the voltaic pile in the Galvani-Volta controversy concerning animal vs. metallic electricity". Journal of the History of Medicine and Allied Sciences. XXIV (2): 140–150. doi:10.1093/jhmas/xxiv.2.140. PMID 4895861.

- Edwards, Paul (10 November 2021). "A Correction to the Record of Early Electrophysiology Research on the 250 th An- niversary of a Historic Expedition to Île de Ré". HAL open-access archive. Retrieved 6 May 2022.

- Al-Khalili, Jim. "Shock and Awe: The Story of Electricity". BBC. Retrieved 9 June 2022.

- Copenhaver, Brian P. (September 1991). "A tale of two fishes: Magical objects in natural history from antiquity through the scientific revolution". Journal of the History of Ideas. 52 (3): 373–398. doi:10.2307/2710043. JSTOR 2710043. PMID 11622951.

- Bigelow, H. B.; Schroeder, W. C. (1953). Fishes of the Western North Atlantic, Part 2. Sears Foundation for Marine Research, Yale University. pp. 80–104.

- Langstroth, L. & Newberry, T. (2000). A Living Bay: the Underwater World of Monterey Bay. University of California Press. p. 222. ISBN 0-520-22149-4.

- Kramer, Bernd (2008). "Electric Organ Discharge". In Marc D. Binder; Nobutaka Hirokawa; Uwe Windhorst (eds.). Encyclopedia of Neuroscience. Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer. pp. 1050–1056. ISBN 978-3-540-23735-8. Retrieved 2012-03-25.

- Burton, R. (2002). International Wildlife Encyclopedia (Third ed.). Marshall Cavendish. p. 768. ISBN 0-7614-7266-5.

- Nelson, J.S. (2006). Fishes of the World (fourth ed.). John Wiley. pp. 69–82. ISBN 0-471-25031-7.

- Compagno, Leonard J.V. and Heemstra, Phillip C. (May 2007) "Electrolux addisoni, a new genus and species of electric ray from the east coast of South Africa (Rajiformes: Torpedinoidei: Narkidae), with a review of torpedinoid taxonomy". Smithiana, Publications in Aquatic Biodiversity, Bulletin 7: 15-49. Retrieved on October 22, 2008.