Tower of Vesunna

The Tower of Vesunna is the vestige of a Gallo-Roman fanum (temple) dedicated to Vesunna, a tutelary goddess of the Petrocorii. The sanctuary was built in the 1st or 2nd century. Vesunna was the Gallo-Roman name for Périgueux, in the Dordogne department, in the Nouvelle-Aquitaine region.

Tour de Vésone | |

.JPG.webp) The Tower of Vesunna and its breach, East side. | |

Shown within France | |

| Location | Périgueux, Périgord, Dordogne |

|---|---|

| Region | Nouvelle-Aquitaine |

| Coordinates | 45°10′46″N 0°42′52″E |

| Altitude | 90 m (295 ft) |

| Type | Fanum (Romano-Celtic Temple) |

| Diameter | 19.6 m (64.3 ft) |

| Height | 24.46 m (80.25 ft) |

| History | |

| Material | Brick and limestone[1] |

| Founded | 1st to 2nd century CE |

| Periods | Classical Antiquity |

| Cultures | Petrocorii, Gallo-Roman |

| Site notes | |

| Excavation dates | 1751, 1820, 1894, 1909 |

| Condition | Ruined |

| Ownership | Municipality |

| Public access | Yes |

| Designated | 1846[1] |

Site

The "Tower" is the remains of a fanum's cella and is located in Périgord, in the center of the Dordogne department, south of Périgueux, in the district called Vésone, on the edge of the Périgueux – Brive railway line. It stands in a public garden known as Jardin de Vésone, 50 meters west of the Vesunna Gallo-Roman Museum which holds the remains of the domus of Bouquets. Its East side is now breached by a gap nearly nine meters wide.[2]

History

The fanum is thought to have been constructed in the 2nd century[1] or perhaps at the end of the 1st.

According to legend, Saint Front made the edifice's breach by driving out demons taking refuge in the tower with his staff. In reality, it was the result of removing large blocks that formed the entryway, causing the collapse of the portion above.[2]

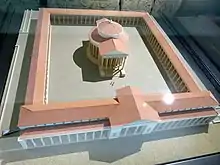

The first excavations inside the tower were undertaken by Msgr. Machéco de Prémeaux. They were halted in 1751 following a workers' panic. They were resumed by the Count de Taillefer and Joseph de Mourcin in 1820, inside and outside the tower. The excavations discovered the base of the circular wall that surrounds the tower. They recognized that the tower was the cella of a temple. This two-meter thick wall is 4.55 m from the exterior façade of the tower. Count de Taillefer assumed that it supported a peristyle (ambulatory), and proposed a reconstruction of the temple.[3]

In 1833, the site, property of Count Wlgrin de Taillefer, was ceded at his death to the city of Périgueux.[2] In 1846, the tower was added to the Monument historique registry.[1]

The construction of the Périgueux – Brive railway line, put into service in 1860, and the development of neighboring streets led to the destruction of the remains of the vast enclosure that protected the temple.[4]

In 1894, the city of Périgueux acquired the garden surrounding the tower to install an archaeological park. It had excavations carried out which confirmed the discoveries of the Count of Taillefer: A large block construction interrupting the circular wall on the opposite side from the breach, connected to a vast set of buildings to the West of the temple. The interior of the tower was cleared to the level of the old foundation. It was during the excavations carried out by Charles Durand from 1906 to 1909 that the ambulatory of the temple was cleared along with its galleries and peristyle through which the entrance to the courtyard of the temple was made.

Dedication

The Count of Taillefer supposed that this temple was dedicated to Isis, but the inscriptions preserved in the Museum of Art and Archeology of Périgord show that the temple was dedicated to the tutelary goddess of Vesunna:

Tute[lae] A[u(gustae) Vesunnae

According to Camille Jullian, "the cult of Tutela has a very Roman origin and it consists in worshipping under this name the unknown god who protects a people, a city, an individual, the deity under the supervision of whom one is placed ... Here is marked the main characteristic of the worship of the tutelae: they are deities of cities, not of peoples ... This is well indicated by the inscriptions: none is dedicated Tutelae populi, civitatis, but simply Tutelae, Tutelae augustae ... TVTELAE VESUNNAE, in the well-known inscription of Périgueux, must be translated not as 'to the tutela of Vesunna' but as, 'to the tutela, Vesunna'.[5]

For Émile Espérandieu, this is the case with The Tower of Vesunna. We do not know who Vesunna was whom the Petrocorii had made their tutela. We may suppose she could have been a spring goddess similar to the god Nemausus, who had given his name to the city of Nîmes and to the whole of the civitate there. It may be related that A bas-relief found to the south-west of Château Barrière depicting a seated panther bears the inscription:[6]

TVT///// A /////

Architecture

The architecture of the temple is a combination of two cultural influences: the Celtic fanum, with a cella surrounded by a low ambulatory or gallery, and the Roman temple model with a columned pronaos opening onto a cella. This synthesis illustrates a cultural fusion, with both Romanization and the persistence of local tradition.[7]

The round cella is all that remains of the temple, which gives it a height of approximately 24.46 meters (27 m when measured from the foundation). It has an external diameter of 19.6 meters. The wall has a thickness of 2.10 m at the base and 1.80 m from a visible recess of the base above the current floor. At this level, the inside diameter of the tower is 17.10 m. Originally, a wall surrounded a rectangular courtyard of more than one and a half hectares (141 m by 122) in which the fanum was centered, raised by a podium which was accessed through a rectangular pronaos with 6 columns.[2] The cella was surrounded by a 23-column peristyle.[8]

Photo Gallery

West side.

West side..JPG.webp) West side, in the Jardin de Vésone.

West side, in the Jardin de Vésone. Detail of the tower's peak.

Detail of the tower's peak. Detail of cavities in the brick.

Detail of cavities in the brick.

References

- "Tour de Vésone". Ministère de la Culture. Retrieved 1 May 2020.

- Penaud, Guy (2003). Le Grand Livre de Périgueux (in French). Périgueux: éditions la Lauze. pp. 574–577. ISBN 2-912032-50-4. OCLC 469308000.

- Count Wlgrin de Taillefer (1821). Antiquités de Vésone, cité gauloise, remplacée par la ville actuelle de Périgueux (in French). Vol. Tome 1. Périgueux: F. Dupont. pp. 328–352. OCLC 467112074.

- Penaud, Guy (2003). Le Grand Livre de Périgueux (in French). Périgueux: éditions la Lauze. p. 111. ISBN 2-912032-50-4. OCLC 469308000.

- Camille, Jullian (1887). Inscriptions romaines de Bordeaux (in French). Vol. Tome 1. Bordeaux: G. Gounouilhou. pp. 61–63. OCLC 18274155.

- Espérandieu, Émile (1893). Musée de Périgueux: Inscriptions antiques. no 3 (in French). Vol. Plates I and II. Périgueux: Imprimerie de la Dordogne. pp. 26–30.

- Gros, Pierre (1991). La France gallo-romaine (in French). Paris: Nathan. pp. 91–93. ISBN 2092843761. OCLC 859831247.

- Temple de Vésone (Information pamphlet), Ville d'art et d'histoire de l'office de tourisme de Périgueux, 2010

Bibliography

- Galy, Édouard (1858). "Vésone et ses monuments sous la domination romaine : amphithéâtre". Société française d'archéologie pour la conservation des monuments historiques (in French). Périgueux and Cambrai: Congrès archéologique de France (25th session): 190–194.

- Galy, Édouard (1875). "Construction et décoration du portique du temple de Vésunna, déesse tutélaire des Pétrocores". Bulletin de la Société historique et archéologique du Périgord (in French) (Tome 2): 45–49.

- De Rouméjoux, Anatole (April 1895). "Fouilles de la tour de Vésone". Bulletin de la Société historique et archéologique du Périgord (in French) (Tome 22): 187–194.

- Roux, Chanoine J. (1920). "La Tour de la Vizonne ou enclos près de la Tour de la Vizonne". Bulletin de la Société historique et archéologique du Périgord (in French) (Tome 47): 96–99.

- Marquis de Fayolle, Gérard (1928). "La tour de Vésone". Congrès Archéologique de France (in French). Paris: Société française d'archéologie (90th session at Périgueux): 30–44.

- Secret, Jean (1978). "Sur un plan de l'amphithéâtre de Vésone levé en 1821 par de Mourcin" (PDF). Bulletin de la Société historique et archéologique du Périgord (in French) (Tome 105): 270–277. Archived from the original (PDF) on 23 December 2019.

- Lauffray, Jean; Will, Ernest; Sarradet, Max; Lacombe, Claude (1990). La Tour de Vésone à Périgueux : temple de Vesunna Petrucoriorum (in French). Vol. (Supplement to Gallia, 49). Paris: CNRS Éditions. pp. 270–277. ISBN 2-222-04183-X. OCLC 22108869.

- (Book review by Philippe Leveau, 1992).

- Barrière, Pierre (1944). "Périgord". Gallia (in French) (2): 245–251.

- See also: Barrière, Pierre (1930). Vesunna Petrucoriorum : histoire d'une petite ville à l'époque gallo-romaine (in French). Périgueux: Ribes. OCLC 163370159. (Book review by Maurice Besnier, 1933).

- Lacombe, Claude (2003). "De la Tour de la Vizonne à la Tour de Vésone. Réflexions autour d'un toponyme et de l'histoire médiévale et moderne d'un monument antique" (PDF). Aquitania (in French) (XIX): 267–281.

- Bost, J.-P.; Didierjean, F.; Maurin, L.; Roddaz, J.-M. (2004). "La Tour de Vésone". Guide archéologique de l'Aquitaine. De l'Aquitaine celtique à l'Aquitaine romane (VIe siècle av. J.-C.-XIe siècle ap. J.-C.) (in French). Pessac: Éditions Ausonius. pp. 149–153. ISBN 978-2-910023-44-7. OCLC 475326154.

- Pénisson, Élisabeth (2018). "Tour de Vésone, sanctuaire de la Tutelle". In Gaillard, Hervé; Mousset, Hélène (eds.). Périgueux. Atlas historique des villes de France (in French). Vol. 53, Tome 2, Sites et Monuments. Pessac: Ausonius. pp. 61–64. ISBN 978-2-35613241-3. OCLC 1085481570.