Trịnh lords

The Trịnh lords (Vietnamese: Chúa Trịnh; Chữ Nôm: 主鄭; 1545–1787), formally titled as “Prince” of Trịnh (Vietnamese: Trịnh vương; chữ Hán: 鄭王), also known as the House of Trịnh or the Trịnh clan (Trịnh thị; 鄭氏), were a noble and feudal clan that ruled Northern Vietnam (then called Tonkin), during the Later Lê dynasty.

Trịnh lords Chúa Trịnh 主鄭 | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1545–1787 | |||||||||||

.svg.png.webp) The seal "Tĩnh Đô vương tỷ" (靖都王璽) of lord Trịnh Sâm.

| |||||||||||

| Status | Lordship within Lê dynasty of Đại Việt | ||||||||||

| Capital | Đông Kinh | ||||||||||

| Common languages | Vietnamese | ||||||||||

| Religion | Neo-Confucianism, Buddhism, Taoism, Vietnamese folk religion | ||||||||||

| Government | Feudal dynastic hereditary military dictatorship | ||||||||||

| Lords | |||||||||||

• 1545–1570 | Trịnh Kiểm (first) | ||||||||||

• 1786–1787 | Trịnh Bồng (last) | ||||||||||

| History | |||||||||||

• Established | 1545 | ||||||||||

• Disestablished | 1787 | ||||||||||

| Currency | Copper-alloy and zinc cash coins | ||||||||||

| |||||||||||

The Trịnh clan and their rivals, the Nguyễn clan, were both referred to by their subjects as "Chúa" (Lord) and controlled Đại Việt, reducing the Later Lê emperors to only titular authority.[1] The title of “Chúa” in this context is therefore comparable to the office of Shogun in Japan. The Trịnh lords traced their descent from Trịnh Khả, a friend and advisor to the 15th-century Vietnamese Emperor Lê Lợi.[2] The Trịnh clan produced 12 lords who dominated the royal court of the Later Lê dynasty and ruled northern Vietnam for more than two centuries.

Origins

Rise of the Trịnh family

After the death of emperor Lê Hiến Tông in 1504, the Lê dynasty began to decline. In 1527, the courtier Mạc Đăng Dung seized the throne from emperor Lê Cung Hoàng, and established the Mạc dynasty ruling the kingdom of Đại Việt. In 1533, the general and Lê royalist Nguyễn Kim revolted against the Mạc dynasty in Thanh Hóa and restored the Lê dynasty. Then he tried to find the Lê dynasty's successor, a son of emperor Lê Chiêu Tông. He found one such prince, Lê Ninh, and enthroned him as Lê Trang Tông. After five years of conflict, most of the southern region of Đại Việt was recaptured by the restored Lê dynasty, but not the capital city, Thăng Long.

The founder of the clan was Trịnh Kiểm, born in Vĩnh Lộc commune, Thanh Hóa province. Trịnh Kiểm was raised in a poor family. He often stole chickens from his neighbors because chicken was his mother's favorite food. When his neighbors found out, they were extremely angry. One day, when Trịnh Kiểm left home, his neighbors abducted his mother and threw her down an abyss. Trịnh Kiểm returned home and panicked due to the disappearance of his mother. When he finally found his mother's body, it was infested with maggots. After the death of his mother, he joined the army of the revived Lê dynasty led by Nguyễn Kim. Because of Trịnh Kiểm's talent, he was given the hand of Kim's daughter Ngọc Bảo, and became his son-in-law. In 1539, Trịnh Kiểm was promoted to general and received the title of Duke of Dực (Dực quận công). In 1545, after the assassination of Nguyễn Kim, Trịnh Kiểm replaced his father-in-law as the commander of the Lê dynasty's royal court and military.

Lê–Mạc Civil War

| History of Vietnam |

|---|

|

| Timeline |

|

|

Government exiled to Lan Xang

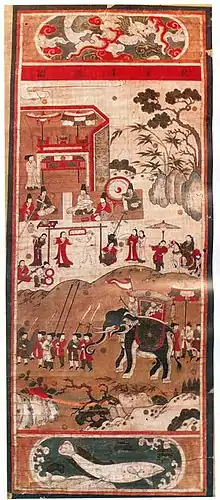

_paper_-_Vietnam_National_Museum_of_Fine_Arts_-_Hanoi%252C_Vietnam_-_DSC05115.JPG.webp)

In 1517, Mạc Đăng Dung overthrew the Lê dynasty. The Lê royalists under Lê Ninh, a descendant of the royal family, escaped to Laos. The Marquis of An Thanh Nguyễn Kim summoned the people who were still loyal to the Lê emperor and formed a new army to begin a revolt against Mạc Đăng Dung. His daughter then married Trịnh Kiểm. Within five years, all of the region south of the Red River was under the control of the Nguyễn–Trịnh army but the two families were unable to conquer Ha Noi until the fall of Mạc dynasty in 1592.

Lê emperor as a figurehead

In 1539 the armies of Nguyễn Kim and Trịnh Kiểm returned to Đại Việt, captured Thanh Hóa province, and crowned Lê Ninh as the emperor Lê Trang Tông. War raged back and forth with the Nguyễn–Trịnh army on one side and the Mạc on the other, until an official Ming delegation determined that Mạc Đăng Dung's usurpation of power was not justified. In 1537, a very large Ming army was sent to restore the Lê family. Although Mạc Đăng Dung managed to negotiate his way out of defeat by the Ming, he had to officially recognize the Lê emperor and Nguyễn–Trịnh rule over the southern part of Vietnam. But the Nguyễn–Trịnh alliance did not accept Mạc rule over the northern half of the country and so the war continued. In 1541, Mạc Đăng Dung died.

A Chinese man shipwrecked in Vietnam in 1688, Pan Dinggui, said in his book "Annan ji you" that the Trinh restored the Lê dynasty to power after Vietnam was struck by disease, thunder and winds when the Le was dethroned, and they initially could not find Lê and Tran dynasty royals to restore to the throne. Pan also said that only the Lê king was met by official diplomats from the Qing, not the Trịnh lord.[3]

Trịnh military dictatorship

Elimination of the Nguyễn clan

Despite the fact that the Mạc dynasty remained at large in the north, Trịnh Kiểm now turned to eliminating the Nguyễn lords' power. Although the Lê dynasty was restored in 1533 with Lê Trang Tông as emperor, Nguyễn Kim was head of government and wielded real authority in the nation. Dương Chấp Nhất, the Mạc-appointed mandarin governing Tây Đô fortress in Thanh Hoa province, decided to surrender to Lê authorities when Nguyễn Kim recaptured the province in 1543.

After seizing Tây Đô citadel and marching onward to attack Ninh Bình, on 20/5/1545, Dương Chấp Nhất invited Kim to visit his military camp. In the hot summer temperature, Dương Chấp Nhất treated Kim to watermelon. After returning for from the party, Kim felt ill and died the same day. Dương Chấp Nhất later pledged allegiance again to the Mạc dynasty.

The government fell into chaos after Kim's death. The successor as the head of government was Kim's eldest son, Nguyễn Uông. However, Uông was secretly assassinated by his brother-in-law Trịnh Kiểm, who later took control of the imperial government.

Usurpation conspiracy

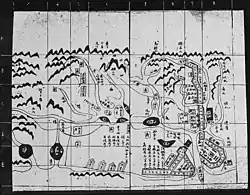

Trịnh lord's villa tea party and troop parade

Trịnh lord's villa tea party and troop parade_-_Painting_of_the_L%C3%AA_dynasty%252C_Vietnam.jpg.webp) Trinh military training.

Trinh military training. Court dress of mandarins and ladies under Lê dynasty- Trịnh lords government.

Court dress of mandarins and ladies under Lê dynasty- Trịnh lords government.

In 1556, Emperor Lê Trung Tông died without an heir. Trịnh Kiểm wanted to seize the Lê dynasty throne but was still worried about public opinion. Therefore, he sought advice from the former mandarin Nguyễn Bỉnh Khiêm, who was living a secluded life. Nguyễn Bỉnh Khiêm advised that Trịnh Kiểm not to take the Lê dynasty's throne, although the Lê dynasty was just a puppet. Trịnh Kiểm decided to put on the Lê dynasty's throne Lê Duy Bang, a 6th-generation descendant of Lê Trừ , the older brother of emperor Lê Thái Tổ. Lê Duy Bang took the throne with the title Lê Anh Tông and the Trịnh lords continued to control the government with the emperor as the figurehead.

Legitimacy struggle

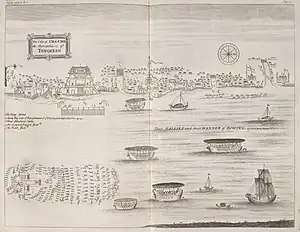

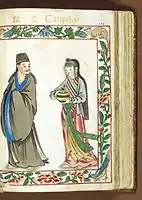

Northern Vietnamese nobleman and wife from Hải Môn harbor (Đàng Ngoài) in 1595.

Northern Vietnamese nobleman and wife from Hải Môn harbor (Đàng Ngoài) in 1595. Two women and a child in Tonkin around the 1700s.

Two women and a child in Tonkin around the 1700s.

In 1570, Trịnh Kiểm died and there was a power struggle between his sons Trịnh Cối and Trịnh Tùng. Simultaneously, the Mạc dynasty army attacked the Lê dynasty from the north and Trịnh Cối was surrendered to the Mạc dynasty. The emperor Lê Anh Tông supported Trịnh Cối as the next Trịnh lord and co-operated with him to defeat Trịnh Tùng. Trịnh Tùng found out about this conspiracy, meaning that Emperor Lê Anh Tông and his four sons had to flee. Later, Trịnh Tùng enthroned Emperor Lê Anh Tông's youngest son, prince Đàm, as the next emperor with title Lê Thế Tông. After that, Trịnh Tùng searched for, captured, and murdered Emperor Lê Anh Tông.

Trịnh–Nguyễn alliance against the Mạc dynasty

Both Trịnh and Nguyễn declared that the Lê dynasty was the legitimate government of Đại Việt. As the years passed, Nguyễn Hoàng became increasingly secure in his rule over the southern province and increasingly independent. While he cooperated with the Trịnh against the Mạc, he ruled the frontier lands as a governor. With the final conquest of the north, the independence of the Nguyễn was less and less tolerable to the Trịnh. In 1600, with the ascension of a new emperor, Lê Kính Tông, Hoàng broke relations with the Trịnh-dominated court, although he continued to acknowledge the Lê emperor. Matters continued like this until Hoàng's death in 1613. The historical victory of the Trịnh over the Mạc was a common theme in public Vietnamese theaters.[4]

The Trịnh–Nguyễn War

In 1620, after the enthronement of another figurehead Lê emperor (Lê Thần Tông), the new Nguyễn leader, Nguyễn Phúc Nguyên, refused to send tax money to the court in Đông Đô to protest the dictatorship of the Trịnh lords. In 1623, Trịnh Tung died, and he was succeeded by his oldest son, Trịnh Tráng. After five years of increasingly hostile talks, fighting broke out between the Trịnh and the Nguyễn in 1627. While the Trịnh ruled over much more populous territory, the Nguyễn had several advantages. First, they initially were on the defensive and rarely launched operations into the north. Second, the Nguyễn were able to take advantage of their contacts with the Europeans, specifically the Portuguese, to produce advanced cannons with the help of European engineers (for more details, see Artillery of the Nguyễn lords). Third, the geography was favorable to them, as the flat land suitable for large, organized armies is very narrow at the border between the Nguyễn lands and the Trinh territories – the mountains nearly reach to the sea. After the first offensive was beaten off after four months of battle, the Nguyễn built two massive, fortified lines that stretched a few miles from the sea to the hills. These walls were built north of Huế (between the Nhật Lệ River and the Sông Hương River). The walls were about 20 feet tall and seven miles long. The Nguyễn defended these lines against numerous Trịnh offensives that lasted (off and on) from 1631 till 1673, when Trịnh Tạc concluded a peace treaty with the Nguyễn lord, Nguyễn Phúc Tần, dividing Vietnam between the two ruling families. This division continued for the next 100 years.

The Long Peace

The Trịnh lords ruled reasonably well, maintaining the fiction that the Lê monarch was the emperor. However, they selected and replaced the emperor as they saw fit, having the hereditary right to appoint many of the top government officials. Unlike the Nguyễn lords, who engaged in frequent wars with the Khmer Empire and Siam, the Trịnh lords maintained fairly peaceable relations with neighboring states. In 1694, the Trịnh lords got involved in a war in Laos, which turned into a multi-sided war with several different Laotian factions as well as the Siamese army. A decade later, Laos had settled into an uneasy peace with three new Lao kingdoms paying tribute to both Vietnam and Siam. Trịnh Căn and Trịnh Cương made many reforms of the government, trying to make it better, but these reforms made the government more powerful and more of a burden to the people which increased their dislike of the government. During the wasteful and inept rule of Trịnh Giang, peasant revolts became more and more frequent. The key problem was a lack of land to farm, though Giang made the situation worse by his actions. The reign of his successor Trịnh Doanh was preoccupied with putting down peasant revolts and wiping out armed gangs which terrorized the countryside.

The Dutch East India Company ceased doing business with the Trịnh lords in 1700.[5][6]

The Trịnh lords started employing eunuchs extensively in the Đàng Ngoài region of the northern Red river delta area of Vietnam as leaders of military units. Trịnh-ruled northern Vietnam used its eunuchs in the military and civilian bureaucracy. Many Buddhist temples had money and land donated by eunuchs who had gained wealth and influence. Field army units, secret police, customs duty taxes, finance, land deeds and military registers and tax harvesting in son Nam province (Binh phien) as well as the position of Thanh Hóa military governor were delegated to eunuchs. The supervisor services, military, civil service and court all had eunuchs appointed to work in them and they faithful followers of the Trịnh lords and a check on the power of civil and military officials.[7] Eunuchs were employed as building project supervisors and provincial governors by Trịnh Cương.[8]

Tây Sơn revolt and Southern Conquest

The long peace came to an end with the Tây Sơn revolt in the south against Trương Phúc Loan, the regent of the Nguyễn lord Nguyễn Phúc Thuần (1765–1777). The Trịnh lord Trịnh Sâm saw the Tây Sơn rebellion as a chance to finally put an end to Nguyễn rule over the south of Vietnam. Inner struggle among the Nguyễn had put a 12-year-old boy in power. The real ruler was the corrupt regent Trương Phúc Loan. Using the popular rule of the regent as an excuse for intervention, in 1774, the hundred-year truce was ended and the Trịnh army led by Hoàng Ngũ Phúc attacked.

Trịnh Sâm's army did what no previous Trịnh army had done and conquered the Nguyễn capital, Phú Xuân (modern-day Huế), in early 1775. The Trịnh army advanced south, defeated the Tây Sơn and forced them to surrender. In the middle of 1775, the Trịnh army, include Hoàng Ngũ Phúc, were hit by a plague. The plagued forced them to withdraw and left the rest of the south to the Tây Sơn.

The Tây Sơn army continued to conquer the rest of the Nguyễn lands. The Nguyễn lords retreated to Saigon but even this city was captured in 1776 and the Nguyễn lords were nearly wiped out. Tây Sơn's leader Nguyễn Nhạc declared himself king in 1778.

End of the Trịnh Viceroy

Trịnh Tông, the eldest son of Trịnh Sâm, feared that the power would fall to his younger brother Trịnh Cán, who was favored by his father. In 1780, Trịnh Sâm became seriously ill, Trịnh Tông used this as a chance to stage a coup d'état. The plan was discovered, many high-ranking mandarins on Trịnh Tông's side were purged, Tông himself were imprisoned.

In 1782, Trịnh Sâm died and passed the power to Trịnh Cán. However, Cán was only five years old at the time, the real ruler was Hoàng Ngũ Phúc's adopted son Hoàng Đình Bảo, who was appointed by Sâm as Cán's assistant. A few weeks after Cán was crowned, Trịnh Tông conspired with the Three Prefectures Army (Vietnamese: Tam phủ quân, chữ Hán: 三府軍) to kill Hoàng Đình Bảo and overthrow Trịnh Cán. However, because Tông was indebted to the army, he could not control them. The army then released Lê Duy Kì, son of prince Lê Duy Vĩ who was killed by Trịnh Sâm in 1771, and forced Lê Hiển Tông to appoint Kì as the successor.

After Hoàng Đình Bảo's death, his subordinate in Nghệ An province Nguyễn Hữu Chỉnh defected to Tây Sơn. He was welcomed by the king of Tây Sơn and became a commander in their army. In summer 1786, Nguyễn Nhạc, who wanted to reclaim the land of the Nguyễn lords taken by the Trịnh in 1775, ordered his brother Nguyễn Huệ and Nguyễn Hữu Chỉnh to attack Trịnh lords, but warned them not to advance further north. After taking Phú Xuân, Nguyễn Hữu Chỉnh convinced Nguyễn Huệ to overthrow Trịnh lords under the banner "Destroy the Trịnh and Aid the Lê (Vietnamese: Diệt Trịnh phù Lê, chữ Hán: 滅鄭扶黎) that would help them gain support from northern people. Trịnh army and the Three Prefectures Army were quickly defeated. Trịnh Tông committed suicide. Emperor Cảnh Hưng died of old age shortly after and passed the throne to Lê Duy Kì (emperor Chiêu Thống).

Nguyễn Nhạc, after having heard of Nguyễn Huệ's insubordination, hastily marched to Thăng Long and ordered all Tây Sơn troops to withdraw. They intentionally left Nguyễn Hữu Chỉnh behind. Chỉnh chased after them and then stayed in his hometown in Nghệ An.

The Tây Sơn's invasion and sudden withdrawal caused a large power vacuum in the North. Trịnh Sâm's younger brother Trịnh Lệ with the support of Dương Trọng Tế marched into Thăng Long and forced Chiêu Thống to grant him the title Viceroy, which would make him a Trịnh lord. Emperor Chiêu Thống did not want to reinstall Trịnh lords, thus he rejected Lệ's request. At the same time, Trịnh Bồng, son of Trịnh Giang, also marched into Thăng Long. Dương Trọng Tế thought Trịnh Lệ was unpopular and defected to Bồng's side, helped him defeated Trịnh Lệ. Famous generals Hoàng Phùng Cơ and Đinh Tích Nhưỡng also joined Trịnh Bồng's faction and pressured Chiêu Thống to grant him the title prince, the emperor reluctantly agreed. He then sent a request to Nguyễn Hữu Chỉnh, who had raised a considerable army in his hometown, to come and aid the emperor once again. Nguyễn Hữu Chỉnh obeyed and marched north, he defeated Trịnh army in Thanh Hoa Province. Trịnh Bồng heard of the news and withdrew to Gia Lâm District with Dương Trọng Tế, Đinh Tích Nhưỡng and Hoàng Phùng Cơ withdrew to Hải Dương and Sơn Tây respectively. Chiêu Thống set Trịnh's palace on fire.

In the next months, Nguyễn Hữu Chỉnh carried out several campaigns against Trịnh Bồng and his followers. He captured and executed Dương Trọng Tế and Hoàng Phùng Cơ, Trịnh Bồng then took refuge at Đinh Tích Nhưỡng's camp. Nguyễn Hữu Chỉnh organized a large assault and completely defeated Trịnh Bồng in fall 1787. Đinh Tích Nhưỡng and Trịnh Bồng ran away, officially ended over 200 of Trịnh lords rule.

Later, when the Qing army was occupying Thăng Long, Trịnh Bồng turned himself in to emperor Chiêu Thống. He was pardoned but was demoted to Duke of Huệ Địch (Huệ Địch công). After the Qing's defeat in early 1789, Bồng fled to the western region of the country, self-proclaimed to be a lord and built a resistance army against the Tây Sơn. He died in early 1791.[9]

After Gia Long founded the Nguyễn dynasty in 1802, he pardoned the Trịnh clan and allowed their descendants to worship their ancestors.

Trịnh foreign relations

In 1620, the French Jesuit scholar Alexandre de Rhodes arrived in Trịnh-controlled Vietnam. He arrived at a mission which had been established at the court in Hanoi around 1615.[10] The priest was a significant person regarding relations between Europe and Vietnam. He gained thousands of converts, created a script for writing Vietnamese using a modified version of the European alphabet, and built several churches. However, by 1630 the new Trịnh lord, Trịnh Tráng, decided that Father de Rhodes represented a threat to Vietnamese society and forced him to leave the country. From this point on, the Trịnh lords periodically tried to suppress Christianity in Vietnam, with moderate success. When the Nguyễn successfully used Portuguese cannon to defend their walls, the Trịnh made contact with the Dutch. The Dutch were willing to sell advanced cannons to the Trịnh. The Dutch, and later the Germans, set up trading posts in Hanoi. For a time, Dutch trade was profitable, but after the war with the Nguyễn ended in 1673, the demand for European weapons rapidly declined. By 1700, the Dutch and English trading posts had closed forever. The Trịnh were careful in their dealings with the Ming dynasty and Manchu-led Qing dynasty of China. Unlike the Nguyễn lords who were happy to accept large numbers of Ming refugees into their lands, the Trịnh did not. When the Qing conquered the Ming and therefore extended the Qing Empire's borders to Northern Vietnam, the Trịnh treated them just like they had treated the Ming Emperors, sending tribute and formal acknowledgements of Qing authority. The Qing intervened twice during the rule of the Trịnh lords, once in 1537, and again in 1788. Both times, the Qing sent an army south because of a formal request for help from the Lê emperors – and both times the intervention was unsuccessful.

Assessment

The Trịnh Lords were, for the most part, intelligent, able, industrious, and long-lived rulers. The unusual dual form of government they developed over two centuries was a creative response to the internal and external obstacles to their rule. They lacked, however, both the power and the moral authority to resolve the contradictions inherent in their system of ruling without reigning. (Encyclopedia of Asian History, "The Trịnh Lords").

It does seem the case that the Trịnh had lost nearly all popularity by the last half of the 18th century. While the Nguyễn lords, or at least Nguyễn Ánh, enjoyed a great deal of support – as his repeated attempts to regain power in the south show – there was no equivalent support for the Trịnh in the north after the Tây Sơn took power.[11]

List of Trịnh lords

| Name | Image | Lifespan | Ruling year(s) | Emperor(s) | Highest attained title | Temple name | Posthumous name |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Trịnh Kiểm

鄭檢 |

.jpg.webp) |

1503–1570 | 1545–1570 | Trang Tông | Thái quốc công

太國公 |

Thế Tổ

世祖 |

Minh Khang Nhân Trí Vũ Trinh Hùng Lược Thái vương

明康仁智武貞雄畧太王 |

| Trịnh Cối

鄭檜 |

_05.png.webp) |

?-1584 | 1570 (6 months) |

Anh Tông | Tuấn Đức hầu

俊德侯 |

||

| Trịnh Tùng

鄭松 |

|

1550–1623 | 1570–1623 | Anh Tông | Bình An vương

平安王 |

Thành Tổ

成祖 |

Cung Hoà Khoan Chính Triết vương

恭和寬正哲王 |

| Trịnh Tráng

鄭梉 |

|

1577–1657 | 1623–1657 | Chân Tông

Thần Tông |

Thanh vương

清王 |

Văn Tổ

文祖 |

Nghị vương

誼王 |

| Trịnh Tạc

鄭柞 |

|

1606–1682 | 1657–1682 | Thần Tông | Tây vương

西王 |

Hoằng Tổ

弘祖 |

Dương vương

陽王 |

| Trịnh Căn

鄭根 |

|

1633–1709 | 1682–1709 | Hy Tông | Định vương

定王 |

Chiêu Tổ

昭祖 |

Khang vương

康王 |

| Trịnh Cương

鄭棡 |

|

1686–1729 | 1709–1729 | Dụ Tông | An vương

安王 |

Hi Tổ

禧祖 |

Nhân vương

仁王 |

| Trịnh Giang

鄭杠 |

|

1711–1762 | 1729–1740 | Duệ Tông | Uy vương

威王 |

Dụ Tổ

裕祖 |

Thuận vương

順王 |

| Trịnh Doanh

鄭楹 |

|

1720–1767 | 1740–1767 | Ý Tông | Minh vương

明王 |

Nghị Tổ

毅祖 |

Ân vương

恩王 |

| Trịnh Sâm

鄭森 |

|

1739–1782 | 1767–1782 | Hiển Tông | Tĩnh vương

靖王 |

Thánh Tổ

聖祖 |

Thịnh vương

盛王 |

| Trịnh Cán

鄭檊 |

|

1777–1782 | 1782 (1 month, Đặng Thị Huệ acts as regent) |

Hiển Tông | Điện Đô vương

奠都王 |

||

| Trịnh Tông

鄭棕 |

|

1763–1786 | 1782–1786 | Hiển Tông | Đoan Nam vương

端南王 |

Linh vương

靈王 | |

| Trịnh Bồng

鄭槰 |

|

1749–1791 | 1786–1787 | Chiêu Thống | Yến Đô vương

晏都王 |

Traditionally, Trịnh Tùng is considered to be the first "lord", but the Trịnh family had held a great amount of power since Trịnh Kiểm.

See also

- Trịnh (surname)

- Trịnh Khả, progenitor of the Trịnh lords

- List of Vietnamese dynasties

- Nguyễn lords

- Trịnh–Nguyễn War

References

- Chapuis, Oscar. A History of Vietnam: From Hong Bang to Tự Đức. Greenwood Publishing Group, 1995. p119ff.

- Đại Việt Thông Sử Page 5 Lê Quý Đôn reprint 1978 "Hoàng đế được biết Trịnh Khả và Lê Lôi đã từng đi đón tiếp con voi tự nước Ai Lao về, tất nhiên am hiểu tiếng nói và văn tự nước Ai Lao, bèn sai hai Tướng này mang tờ thông điệp sang bảo Quốc Vương nước Ai Lao rằng: "Quốc gia tôi .."

- Herr, Joshua (2017). Fraught Collaboration: Diplomacy, Intermediaries, and Governance at the China-Vietnam Border, Seventeenth and Eighteenth Centuries (PDF) (A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in History). UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles. pp. 85, 110.

- Knosp, Gaston (1902). "Das annamitische Theater". Globus. 82 (1): 11–15. ISSN 0935-0535.

- Anh Tuan, Hoang. "Letter from the King of Tonkin concerning the termination of the trading relation with the VOC, 10 February 1700". Arsip Nasional Republik Indonesia.

- Hoang Anh Tuan, “Letter from the King of Tonkin concerning the termination of the trading relation with the VOC, 10 February 1700”. In: Harta Karun: Hidden Treasures on Indonesian and Asian-European History from the VOC Archives in Jakarta, document 3. Jakarta: Arsip Nasional Republik Indonesia, 2013.

- Antoshchenko, Vladimir (2002). "THE TRINH RULING FAMILY IN VIETNAM IN THE 16TH – 18TH CENTURIES" (PDF). Asian and African Studies. Centre for Vietnamese Studies, Institute of Asia and Africa, Moscow University, Russia. 11 (2): 161–168.

- Taylor, K. W. (2013). A History of the Vietnamese. Cambridge University Press. p. 351. ISBN 978-1107244351. Alt URL

- Hoàng Xuân Hãn, Phe chống đảng Tây Sơn ở Bắc với tập "Lữ Trung Ngâm" (The anti-Tây Sơn factions in the north and the "Lữ Trung Ngâm" collection), Tập san Sử Địa, 1971–1972.

- Tigers in the Rice by W. Sheldon (1969), p. 26.

- Vietnam, Trials and Tribulations of a Nation D. R. SarDesai, pg. 39, 1988

External links

- List of the Trịnh lords and the nominal Lê emperors

- Encyclopedia of Asian History, Volumes 1–4. 1988. Charles Scribner's Sons, New York. – "Trịnh Lords" Article by James M. Coyle, based on the work of Thomas Hodgkin.

- The Encyclopedia of Military History by R. Ernest Dupuy and Trevor N. Dupuy. Harper & Row (New York).

- Coins of Vietnam – with short historical notes

- Southeast Asia to 1875 – by Sanderson Beck

- World Statesmen.org – Vietnam

- Tay Sơn Web Site by George Dutton (has a great bibliography)

- A glimpse of Vietnamese history – contains some errors