Tragic hero

A tragic hero (or tragic heroine if they are female) is the protagonist of a tragedy. In his Poetics, Aristotle records the descriptions of the tragic hero to the playwright and strictly defines the place that the tragic hero must play and the kind of man he must be. Aristotle based his observations on previous dramas.[1] Many of the most famous instances of tragic heroes appear in Greek literature, most notably the works of Sophocles and Euripides.

Aristotle's tragic hero

In Poetics, Aristotle suggests that the hero of a tragedy must evoke a sense of pity and fear within the audience, stating that “the change of fortune presented must not be the spectacle of a virtuous man brought from prosperity to adversity."[2] In essence, the focus of the hero should not be the loss of his goodness. He establishes the concept that pity is an emotion that must be elicited when, through his actions, the character receives undeserved misfortune, while the emotion of fear must be felt by the audience when they contemplate that such misfortune could possibly befall themselves in similar situations. Aristotle explains such change of fortune "should be not from bad to good, but, reversely, from good to bad.” Such misfortune is visited upon the tragic hero "not through vice or depravity but by some error of judgment." This error, or hamartia, refers to a flaw in the character of the hero, or a mistake made by the character.

Therefore, the Aristotelian hero is characterized as virtuous but not "eminently good," which suggests a noble or important personage who is upstanding and morally inclined while nonetheless subject to human error. Aristotle's tragic heroes are flawed individuals who commit, without evil intent, great wrongs or injuries that ultimately lead to their misfortune, often followed by tragic realization of the true nature of events that led to this destiny.[3] This means the hero still must be – to some degree – morally grounded. The usual irony in Greek tragedy is that the hero is both extraordinarily capable and highly moral (in the Greek honor-culture sense of being duty-bound to moral expectations), and it is these exact, highly-admirable qualities that lead the hero into tragic circumstances. The tragic hero is snared by his own greatness: extraordinary competence, a righteous passion for duty, and (often) the arrogance associated with greatness (hubris).

In other media

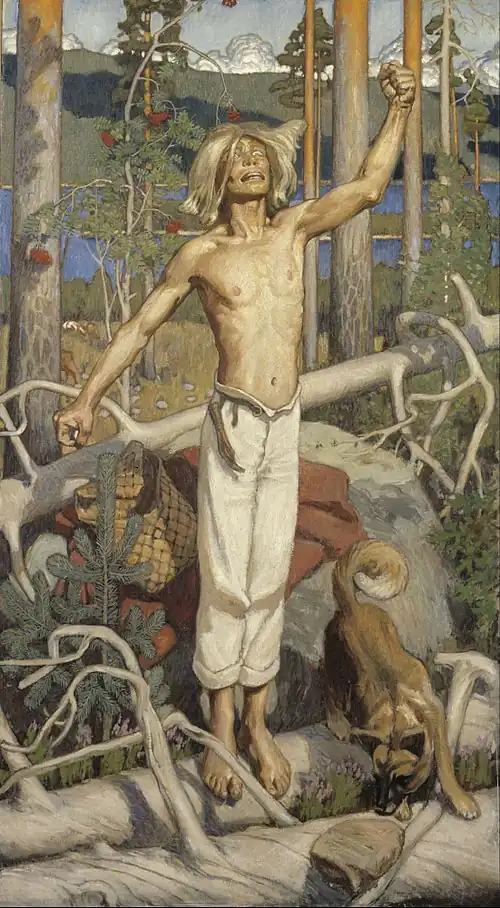

The influence of the Aristotelian hero extends past classical Greek literary criticism. Greek theater had a direct and profound influence on Roman theater and formed the basis of Western theater, with other tragic heroes including Macbeth in William Shakespeare's The Tragedy of Macbeth, and Othello in his Othello.[4]Kullervo, a tragic hero from the Karelian and Finnish 19th century epic poetry Kalevala by Elias Lönnrot, curses beasts from the woods to attack his tormenter, the Maiden of the North. J. R. R. Tolkien wrote an interpretation of the Kullervo cycle in 1914; the piece was finally published in its unfinished form as The Story of Kullervo.[5]

Theatre deeply influences a wide variety of arts throughout the world, in diverse media such as literature, music, film, television and even video games. Many iconic characters featured in these genres follow the archetype of the tragic hero. Examples of such characters include Anakin Skywalker from George Lucas' Star Wars films, Jay Gatsby from The Great Gatsby and Eddard Stark from George R. R. Martin's novel series A Song of Ice and Fire and the HBO television series adaptation Game of Thrones. Some film historians regard Michael Corleone of The Godfather as a tragic hero, although using traditional literary conventions, the character would more closely fit the role of anti-hero.[6]

References

- Aristotle, On Poetics, Ingram Bywater

- S.H. Butcher, The Poetic of Aristotle (1902), pp. 45-47

- Charles H. Reeves, The Aristotelian Concept of The Tragic Hero, Vol. 73, No. 2 (1952), Published by: The Johns Hopkins University Press JSTOR 291812 pp. 172-188

- Duckworth, Courtney (23 January 2015). "How Accurate Is American Sniper?". Slate.com. Retrieved 4 March 2020.

- "Tolkienin Kalevala-tarina julkaistaan sadan vuoden viipeellä – Kullervo vannoo kostoa taikuri-Untamolle" [Tolkien's Kalevala story published after a hundred-year lag – Kullervo vows revenge on Untamo the magician] (in Finnish). Retrieved 2015-06-29.

- AFI's 100 Years... 100 Heroes and Villains Archived October 23, 2007, at the Wayback Machine

Sources

- Carlson, Marvin. 1993. Theories of the Theatre: A Historical and Critical Survey from the Greeks to the Present. Expanded ed. Ithaca and London: Cornell UP. ISBN 0-8014-8154-6.

- Janko, Richard, trans. 1987. Poetics with Tractatus Coislinianus, Reconstruction of Poetics II and the Fragments of the On Poets. By Aristotle. Cambridge: Hackett. ISBN 978-0-87220-033-3.

- Pavis, Patrice. 1998. Dictionary of the Theatre: Terms, Concepts, and Analysis. Trans. Christine Shantz. Toronto and Buffalo: U of Toronto P. ISBN 978-0-8020-8163-6.