Trans-Canada Highway

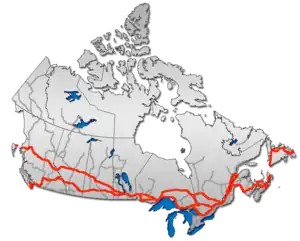

The Trans-Canada Highway (French: Route Transcanadienne; abbreviated as the TCH or T-Can)[3] is a transcontinental federal–provincial highway system that travels through all ten provinces of Canada, from the Pacific Ocean on the west coast to the Atlantic Ocean on the east coast. The main route spans 7,476 km (4,645 mi) across the country, one of the longest routes of its type in the world.[4] The highway system is recognizable by its distinctive white-on-green maple leaf route markers, although there are small variations in the markers in some provinces.

Trans-Canada Highway | |

|---|---|

| Route Transcanadienne | |

| |

| Route information | |

| Length | 7,476 km[1] (4,645 mi) Main route |

| Existed | July 30, 1962[2]–present |

| Major junctions | |

| From | Victoria and Haida Gwaii, British Columbia |

| To | St. John's, Newfoundland and Labrador |

| Location | |

| Country | Canada |

| Major cities | Victoria, Vancouver, Abbotsford, Kamloops, Calgary, Edmonton, Regina, Saskatoon, Winnipeg, Thunder Bay, Greater Sudbury, Peterborough, Ottawa, Montreal, Quebec City, Charlottetown, Fredericton, Moncton, St. John's |

| Highway system | |

|

| |

While by definition the Trans-Canada Highway is a highway system that has several parallel routes throughout most of the country, the term "Trans-Canada Highway" often refers to the main route that consists of Highway 1 (British Columbia, Alberta, Saskatchewan, and Manitoba), Highways 17 and 417 (Ontario), Autoroutes 40, 25, 20 and 85 (Quebec), Highway 2 (New Brunswick), Highways 104 and 105 (Nova Scotia) and Highway 1 (Newfoundland). This main route starts in Victoria and ends in St. John's, passes through nine of the ten provinces and connects most of the country's major cities, including Vancouver, Calgary, Winnipeg, Ottawa, Montreal, Quebec City and Fredericton. One of the main route's eight other parallel routes connects to the tenth province, Prince Edward Island.

While the other parallel routes in the system are also technically part of the Trans-Canada Highway, they are usually considered either secondary routes or different highways all together. For example, Highway 16 throughout Western Canada is part of the Trans-Canada Highway system, but is almost exclusively referred to as the Yellowhead Highway and is often recognized as its own highway under that name. In comparison, Highway 1 in Western Canada is always referred to as the Trans-Canada Highway, and has a significantly higher traffic volume with a route passing through more major cities than the less important Highway 16 (Yellowhead) TCH route. Therefore Highway 1 is usually considered to be part of the main Trans-Canada Highway route, while Highway 16 is not, although it may be considered a second mainline corridor as it serves a more northerly belt of major cities, as well as having its own Pacific terminus.

Although the TCH network is strictly a transcontinental system, and does not enter any of Canada's three northern territories or run to the United States' border, it does form part of Canada's overall National Highway System (NHS), which does provide connections to the Northwest Territories, Yukon and the border, although the NHS (apart from the TCH sections) is unsigned.[5]

Jurisdiction and designation

.svg.png.webp)

.svg.png.webp)

Canada's National Highway System is not under federal jurisdiction or coordination, as highway construction and maintenance are entirely under the jurisdiction of the individual provinces, which also handle route numbering on the Trans-Canada Highway. The Western provinces have voluntarily coordinated their highway numbers so that the main Trans-Canada route is designated Highway 1 and the Yellowhead route is designated Highway 16 throughout. Prince Edward Island and Newfoundland and Labrador also designate Highway 1 as their section of the TCH, while New Brunswick utilizes Highway 2 (a separate important highway—albeit non-TCH—is Highway 1 in that province). East of Manitoba, the highway numbers change at each provincial boundary, or within a province (especially in Ontario and Quebec) as the TCH piggybacks along separate provincial highways (which often continue as non-TCH routes outside the designated sections) en route. In addition, Ontario and Quebec use standard provincial highway shields to number the highway within their boundaries, but post numberless Trans-Canada Highway shields alongside them to identify it. As the Trans-Canada route was composed of sections from pre-existing provincial highways, it is unlikely that the Trans-Canada Highway will ever have a uniform designation across the whole country.

Highway design and standards

Unlike the Interstate Highway System in the United States, the Trans-Canada Highway system has no national construction standard, and was originally built mostly as a two-lane highway with few multi-lane freeway or expressway sections, similar to the older United States Numbered Highway System. As a result, highway construction standards vary considerably among provinces and cities. In much of British Columbia, Ontario, and throughout Prince Edward Island and Newfoundland and Labrador, the Trans-Canada Highway system is still in its original two-lane state. On the other hand, New Brunswick is the only province to have its whole length of the main Trans-Canada Highway route at a four-lane freeway standard. In Quebec, most sections of the TCH network overlap with the province's Autoroute freeway system, resulting in the Trans-Canada Highway following freeways throughout most of Quebec as well. Alberta and Saskatchewan also have widened large portions of their Trans-Canada Highway network, with their entire length of Highway 1 and even most of Highway 16 widened to a four-lane divided highway, albeit with at-grade intersections in most areas. British Columbia is actively working on converting its section of Highway 1 east of Kamloops to a four-lane, non-freeway route. Currently, over half of the mainline Trans-Canada Highway is still in its original two-lane state, with no bypasses, interchanges and few passing opportunities. Only about 15 per cent of the mainline route is at freeway standards similar to those of the Interstate Highway system.

Like former U.S. Route 66, the many non-expressway sections of the Trans-Canada Highway often form the Main streets of communities, with a wide variety of small businesses and traveller services having signage and buildings directly adjacent to the Trans-Canada Highway, and in some cases even driveways directly off the highway. These tourist- and traveller-oriented business districts tend to generate significant revenue and employment for their respective communities, especially in the summer. However, the heavy commercial development on many sections of the highway can also cause traffic problems, due to the lower speed limits, signal lights and crosswalks required to service them.

Freeway portions are rare compared to the length of the Trans-Canada Highway network. They exist over significant distances in British Columbia's Lower Mainland, between Calgary and Banff, in Ontario and in Quebec where the network overlaps portions of those provinces' 400-series highways and Autoroutes, across all of New Brunswick, and in the western part of Nova Scotia. Outside of these freeway areas, the highway ranges from being a high-speed four-lane rural expressway to a narrow, winding, two-lane route, subject to dangerous driving conditions and frequent closures. In many cities, the main highway routes are forced onto busy arterial streets with many traffic lights. Examples of this are where the route passes through Victoria, Nanaimo, Kamloops, and Salmon Arm, Calgary and Winnipeg. A TCH-designated expressway bypass exists around Winnipeg, although Highway 1 proper still passes through the city on surface streets. In Calgary, the Stoney Trail provides a freeway bypass around its urban arterial section of Trans-Canada Highway, although Stoney Trail itself is not considered part of the TCH system.

The Trans-Canada Highway is not always the preferred route between two cities, or even across the country. For example, the vast majority of traffic travelling between Hope, British Columbia, and Kamloops takes the Coquihalla Highway via Merritt, a freeway, rather than the semi-parallel, but longer, Trans-Canada Highway route via Cache Creek, which remains a windy two-lane road. Another example is that much long-distance traffic between Western and Eastern Canada will drive south into the United States and use the Interstate Highway System, rather than the long, windy, two-lane Trans-Canada Highway through Northern Ontario, which is slow and subject to frequent closures.

Main route

British Columbia

The main Trans-Canada Highway is uniformly designated as Highway 1 across the four western provinces. The British Columbia section of Highway 1 is 1,045 km (649 mi) long, beginning in Victoria at the intersection of Douglas Street and Dallas Road (where the "Mile 0" plaque stands), and ending on the Alberta border at Kicking Horse Pass. The highway starts by passing northward along the east coast of Vancouver Island for 99 km (62 mi) to Nanaimo along a mostly four-lane, heavily-signalized highway. After passing through downtown Nanaimo on a small arterial road it enters the Departure Bay Terminal and crosses the Strait of Georgia to Horseshoe Bay via BC Ferries. From there, it travels through Metro Vancouver on a four- to eight-lane freeway before leaving the city and continuing as a four-lane freeway eastward up the Fraser Valley to Hope. There the Trans-Canada Highway exits the freeway and turns north for 186 km (116 mi) through Fraser Canyon and Thompson Canyon toward Cache Creek, mostly as a two-lane rural highway with only occasional traffic lights. Highway 5 provides a more direct freeway route between Hope and Kamloops, leaving the Fraser Canyon route (the official TCH route) as more of a scenic option or for local traffic. Approaching Kamloops, Highway 1 re-enters a short freeway alignment (briefly concurrent with Highways 5 and 97), before passing through Kamloops itself as a four-lane signalized highway. From Kamloops, the highway continues east as a mostly two-lane rural highway through the Interior of British Columbia, with occasional passing lanes. It widens to a signalized four-lane arterial road for short stretches in Salmon Arm, Revelstoke and Golden, but has no signal lights on it for most of its length. The highway crosses two high passes along its route: Rogers Pass in Glacier National Park, and Kicking Horse Pass in Yoho National Park. At Kicking Horse Pass, the highest point on the whole Trans-Canada Highway system is reached, at 1,627 m (5,338 ft).

Highway 1 in British Columbia has four freeway segments. These are in Victoria, through the Lower Mainland, and west and east of Kamloops (the second and third of those sections are connected by the Coquihalla Highway, which is a freeway route that is the preferred route for through traffic). The rest of the highway is either a heavily-signalized four-lane route or a winding two-lane route with passing lanes and occasional four-lane sections. The freeway section of Highway 1 through Vancouver is notorious for its traffic, and is one of the most congested roads in Canada. The Highway 1 approach from North Vancouver to the Ironworkers Crossing is known to regularly form traffic jams that are an hour long during rush hour. Further east, another section of Highway 1 freeway between Langley and Abbotsford is locally known for being congested all day long and having frequent accidents. Both of these bottlenecks are caused by a lack of effective alternative routes, since Highway 1 is the only major east–west route through the city and the outdated four-lane freeway is used beyond its design capacity. Smaller traffic delays are known to exist on the highway during rush hour in Kamloops and Victoria, and during long weekends at the Revelstoke and Kicking Horse Canyon bottlenecks. In addition to the traffic problems, Highway 1 over Kicking Horse Canyon is considered Canada's most dangerous road due to frequent crashes, substandard highway construction, avalanche closures and terrible winter driving conditions.

Traffic moving eastbound or westbound between Vancouver Island and the Interior of the province can bypass the Departure Bay–Horseshoe Bay Ferry and the busiest sections of Highway 1 in Metro Vancouver using British Columbia Highway 17 (South Fraser Perimeter Road on the Mainland). This route runs from Victoria to Delta and Surrey by way of the Tsawwassen Ferry Terminal, and provides a shortcut that avoids the entire circuitous Vancouver Island route of the Trans-Canada Highway, with its numerous traffic lights and bottlenecks.

Speed limits on the Mainland segment of the Trans-Canada Highway in British Columbia range from 90–100 km/h (56–62 mph), although in town it can be as low as 50 km/h (31 mph). A combination of difficult terrain and growing urbanization limits posted speeds on the Vancouver Island section to 50 km/h (31 mph) in urban areas, 80 km/h (50 mph) over the Malahat and through suburban areas, and a maximum of 90 km/h (56 mph) in rural areas.

The Government of British Columbia is attempting to fix the bottleneck at the Ironworkers approach by introducing a stoplight merge feature, improving outdated interchanges, and improving bus transit.[6] In addition, the Government of British Columbia is widening the freeway to six lanes in Abbotsford.[7] The Government of British Columbia also is planning on widening the entire length of the highway between Kamloops and Alberta to four lanes by 2050 for safety and traffic operation. The later plan has several widening projects under way, amounting to 20 km (12 mi) of new four-lane highway under construction. Particularly important is current work to widen the remaining 5 km (3.1 mi) of winding two-lane highway in the Kicking Horse Canyon outside Yoho National Park, which had long been a traffic bottleneck and prone to frequent closure (travel speeds on this section of TCH are often as low as 30 km/h; 20 mph). The construction of no fewer than five bridges and extensive blasting is underway to widen the Trans-Canada to a 100 km/h (60 mph) four-lane highway though the area, with completion scheduled for 2023. To avoid delay to traffic, the construction is largely done at night or during the shoulder season, with a 90-minute-long detour route in effect during those times. A complete closure of the road went into effect from April 19 to May 20, 2022, with additional partial closures from May 24 until fall.[8][9]

Alberta, Saskatchewan and Manitoba

The Trans-Canada Highway through the three prairie provinces is 1,667 km (1,036 mi) long. It starts at the border with British Columbia at Kicking Horse Pass, and runs all the way to the Ontario border at Whiteshell. The highway continues through Alberta, running east for 206 km (128 mi) as Alberta Highway 1 to Lake Louise, Banff, Canmore and Calgary. This section of the highway passes through Banff National Park, and has significant tourism. The section of Highway 1 through Banff National Park was also one of the first highways in North America to have wildlife crossing structures and fencing installed on it. After leaving the mountains it enters Calgary, where it becomes known as 16 Avenue N, a busy six-lane street with many signalized intersections.[10] The northwest and northeast segments of Stoney Trail (Highway 201) were completed in 2009, serving as an east–west limited-access highway (freeway) that bypasses the Calgary segment of Highway 1 (although Stoney Trail itself is not part of the Trans-Canada Highway network). For the next 293 km (182 mi) after Calgary, the Trans-Canada Highway continues as a four-lane expressway, with few stops along its route. Medicine Hat is served by a series of six interchanges, after which the Trans-Canada crosses into Saskatchewan on the way to Moose Jaw.[10] The highway mainly travels straight as a four-lane route for most of these sections. The expressway continues 79 km (49 mi) east to the city of Regina, and skirts around the city on the Regina Bypass, the most expensive infrastructure project in Saskatchewan to date. Beyond Regina, it continues east for 486 km (302 mi), across the border with Manitoba, to the cities of Brandon and Portage la Prairie, and finally 84 km (52 mi) east to Winnipeg.[11] The southern portion of Winnipeg's Perimeter Highway (Highway 100) is part of the Trans-Canada Highway system, and bypasses the city with a mix of traffic lights and interchanges, while Highway 1 continues through central Winnipeg as a signalized arterial road.[11]

With the exception of a 15 km (10 mile) long stretch of two-lane highway just west of the Ontario border, the entire length of Highway 1 through the Prairie Provinces is a four-lane highway. While the only true freeway sections of the route are along the Regina Bypass, in Medicine Hat and between Calgary and Banff, the whole highway is largely stoplight-free, with "split" at-grade intersections forming the vast majority of the junctions. Because the highway has bypasses around all of the major cities traffic congestion is virtually non-existent anywhere on Highway 1 through the Prairies. These sections of divided highway are also generally reliable and safe to travel on, unlike sections of Highway 1 in British Columbia and Ontario.

The speed limit is restricted to 90 km/h (56 mph) through national parks in Canada, including Banff National Park. East of Banff, traffic on most of Highway 1 through Alberta, Saskatchewan, and Manitoba[12] is limited to 110 km/h (68 mph), but is 100 km/h (62 mph) east of Winnipeg.

Alberta Transportation has plans to widen its whole length of Highway 1 to a four-to-eight-lane freeway by replacing all at-grade intersections with overpasses. However, it has not set a timeline for this project. There has also been talk of re-aligning over 100 km (60 mi) of Highway 1 from its existing route to an widened Highway 22X when the west sections of Calgary Ring Road are complete, resulting in a designated Trans-Canada Highway bypass route south of the city, but no official announcements have been made.

Ontario

East of Winnipeg, the highway continues for over 200 km (120 mi) to Kenora, Ontario. At the provincial border, the expressway becomes an arterial highway and the numeric designation of the highway changes from 1 to 17. It is signed with a provincial shield along with a numberless Trans-Canada Highway sign, and continues as an arterial highway along the main route across Northern and Eastern Ontario, until widening out to a freeway at Arnprior, near Ottawa.[13] In Kenora, the Trans-Canada designation includes both the main route through the city's urban core, and the 33.6 km (20.9 mi) Highway 17A bypass route to the north. The existing branch from Kenora continues east for 136 km (85 mi) to Dryden.[13] This section of highway passes through the Canadian Shield, a rugged forested area with thousands of lakes. There are many cottage communities along this section of the Trans-Canada Highway, some of which have their driveways directly onto the highway.

Highway 11/Highway 17 proceeds southeast for 65 km (40 mi) to Thunder Bay, then northeast for 115 km (71 mi) to Nipigon.[13] An 83-kilometre (52 mi) segment of the Trans-Canada Highway between Thunder Bay and Nipigon is commemorated as the Terry Fox Courage Highway.[13] Fox was forced to abandon his cross-country Marathon of Hope run here, and a bronze statue of him was later erected in his honour. The highway is the only road that connects eastern and western Canada. On January 10, 2016, the Nipigon River Bridge suffered a mechanical failure, closing the Trans-Canada Highway for 17 hours; the only alternative was to go through the United States, around the south side of Lake Superior.[14]

Highway 17 proceeds east from Nipigon for 581 km (361 mi) along the northern and eastern coast of Lake Superior. Between Wawa and Sault Ste. Marie, the highway crosses the Montreal River Hill, which sometimes becomes a bottleneck on the system in the winter when inclement weather can make the steep grade virtually impassable.[15] At Sault Ste. Marie, the main route turns eastward for 291 km (181 mi) to Sudbury.

The mainline route then continues east from Sudbury for 151 km (94 mi) to North Bay. The northern route rejoins the mainline here, which continues 339 km (211 mi) to Arnprior where it widens to a freeway and becomes Highway 417. The freeway continues to Ottawa passing through the city on Highway 417, which is between six and eight lanes wide at this point. In Southern Ontario, the speed limit is generally 80 km/h (50 mph) on the Trans-Canada, while in Northern Ontario it is 90 km/h (56 mph). Sections routed along Highway 417 outside urban Ottawa feature a higher limit of 110 km/h (68 mph).[16]

While Highway 17 and 417 are largely free from traffic congestion except from minor rush hour delays on Ottawa's stretch of Highway 417, the non-freeway sections are subject to frequent closures due to crashes, especially in winter. It is considered a dangerous route due to its extensive outdated sections of winding two-lane highway. Because this section of the highway passes through a largely undeveloped and forested area, collisions with animals are a common cause of crashes.

Ontario plans to eventually extend the 417 freeway to Sudbury, which will widen the section of the mainline TCH between Ottawa and Sudbury to four-lane freeway standards. However, there is no funding secured for such a project, as Ontario is currently focusing on extending Highway 400 to Sudbury along the Highway 69 corridor (which is part of the Georgian Bay TCH route).

It is notable that the Trans-Canada largely bypasses Canada's most heavily populated region, the Golden Horseshoe area of Southern Ontario, which includes Canada's largest city; Toronto. However, a short section of the Central Ontario branch does pass through the rural northeastern edge of Durham Region at both Sunderland and Beaverton, which is officially part of the Greater Toronto Area. Access to Toronto itself from the mainline from Northern Ontario is via the non-TCH southern section of Highway 400, while access from Toronto to Quebec and points east is via Highway 401 (North America's busiest highway and a major national highway in itself),[17] a short non-TCH section of Autoroute 20, and A-30, where the Trans-Canada is joined at A-40 just west of Montreal.

Quebec

From Ottawa, the Trans-Canada Highway continues as a freeway and proceeds 206 km (128 mi) east to Montreal, as Highway 417 in Ontario (and the Queensway in Ottawa) and Autoroute 40 in Quebec.[16] The Trans-Canada assumes the name Autoroute Métropolitaine (also known as "The Met" or "Metropolitan Boulevard") as it traverses Montreal as an elevated freeway. At the Laurentian interchange, in Montreal, the Abitibi route (Highway 66, Route 117, A-15) rejoins the main TCH line. The TCH then follows Autoroute 25 southbound, crossing the St. Lawrence River through the 6-lane Louis-Hippolyte Lafontaine Bridge–Tunnel, and proceeds northeast on Autoroute 20 for 257 km (160 mi) to Lévis (across from Quebec City).

East of Lévis, the Trans-Canada Highway continues on Autoroute 20 following the south bank of the St. Lawrence River to a junction just south of Rivière-du-Loup, 173 km (107 mi) northeast of Lévis. At that junction, the highway turns southeast and changes designation to Autoroute 85 for 13 km (8 mi), and then downgrades from a freeway to Route 185, a non-Autoroute (not limited-access) standard highway until Saint-Louis-du-Ha! Ha! where Autoroute 85 resumes once again. The portion from Autoroute 20 to Edmundston, New Brunswick is approximately 120 km (75 mi) long.[16]

Since the Trans-Canada Highway for the most part follows Quebec's Autoroute System, which is always composed of a minimum four-lane freeway, travel through Quebec is generally, safe, fast and congestion free. The exception is the route through Montreal, which can be prone to traffic congestion. However, drivers can bypass the city on the tolled Autoroute 30, which is not part of the Trans-Canada.

The maximum speed limit on the Quebec Autoroute System (including the TCH) is a strictly enforced 100 km/h (62 mph). However, the speed limit may be lower in select spots, such as through tunnels or major interchanges.

Quebec is currently working on widening the last remaining 36 km (22 mile) long two-lane section of Trans-Canada Highway along 185 to an Autoroute, with 9 km (5.6 mi) of new freeway opened in 2021, and another 20 km (12.4 mi) of freeway currently under construction. Once this project is complete, the two sections of Autoroute 85 will be joined, and all of Quebec's Mainline Trans-Canada Highway route will be minimum four-lane freeway standards. This will also result in the TCH becoming a continuous freeway from Arnprior, Ontario, to Lower South River, Nova Scotia.

New Brunswick

The Trans-Canada Highway crosses into New Brunswick and becomes Route 2 just northwest of Edmundston. From Edmundston, the highway (again signed exclusively with the TCH shield) follows the Saint John River Valley, running south for 170 km (110 mi) to Woodstock (parallelling the Canada–US border) and then east for another 102 km (63 mi) to pass through Fredericton. 40 km (25 mi) east of Fredericton, the Saint John River turns south, whereby the highway crosses the river at Jemseg and continues heading east to Moncton another 135 km (84 mi) later. On November 1, 2007, New Brunswick completed a 20-year effort to convert its entire 516 km (321 mi) section of the Trans-Canada Highway into a four-lane limited-access divided highway. The highway has a speed limit of 110 km/h (68 mph)[16] on most of its sections in New Brunswick.

New Brunswick was the first province where the main route of the Trans-Canada Highway was made entirely into a four-lane limited-access divided highway.

From Moncton, the highway continues southeast for 54 km (34 mi) to a junction at Aulac close to the New Brunswick–Nova Scotia border (near Sackville). Here, Trans-Canada Highway again splits into two routes, with the main route continuing to the nearby border with Nova Scotia as Route 2, and a 70 km (43 mi) route designated as Route 16 which runs east to the Confederation Bridge at Cape Jourimain.[16]

Nova Scotia

From the New Brunswick border, the main Trans-Canada Highway route continues east into Nova Scotia at Amherst, where it settles onto Nova Scotia Highway 104. Southeast of Amherst, near Thomson Station, the highway traverses the Cobequid Pass, a 45 km (28 mi) tolled section ending at Masstown, before passing by Truro, where it links with Highway 102 to Halifax, 117 km (73 mi) east of the New Brunswick border. Halifax, like Toronto, is a provincial capital that the Trans-Canada Highway does not pass through. Beyond Truro, the highway continues east for 57 km (35 mi) to New Glasgow where it meets Highway 106, before continuing to the Canso Causeway which crosses the Strait of Canso onto Cape Breton Island near Port Hawkesbury. From the Canso Causeway, the highway continues east, now designated as Highway 105 on Cape Breton Island, until reaching the Marine Atlantic ferry terminal at North Sydney.[16]

Newfoundland and Labrador

From North Sydney, a 177 km (110 mi) ferry route, operated by the Crown corporation Marine Atlantic, continues the highway to Newfoundland, arriving at Channel-Port aux Basques, whereby the Trans-Canada Highway assumes the designation of Highway 1 and runs northeast for 219 km (136 mi) through Corner Brook, east for another 352 km (219 mi) through Gander and finally ends at St. John's, another 334 km (208 mi) southeast, for a total of 905 km (562 mi) crossing the island.[16] The majority of the Trans-Canada Highway in Newfoundland is undivided, though sections in Corner Brook, Grand Falls-Windsor, Glovertown and a 75 km (47 mi) section from Whitbourne to St. John's are divided.[16]

"Mile zero"

.jpg.webp)

Although there does not appear to be any nationally sanctioned "starting point" for the entire Trans-Canada Highway system, St. John's has adopted this designation for the section of highway running in the city. The foot of East White Hills Road in St. John's, near Logy Bay Road, would be a more precise starting point of the highway, where the road meets and transfers into the start of the Trans-Canada Highway. The terminus of the Trans-Canada Highway in Victoria, at the foot of Douglas Street and Dallas Road at Beacon Hill Park, is also marked by a "mile zero" monument. St. John's downtown arena, Mary Brown's Centre, was originally branded under naming rights as "Mile One Centre" in reference to the geography of the region.[18][19]

The usage of miles instead of kilometres at both designations dates back to when the Trans-Canada Highway was completed in 1962, prior to metrication in Canada.

Other routes

Highway 16 (Yellowhead Highway)

The Yellowhead Highway is a 2,859 km (1,777 mi) highway in Western Canada, running from Masset, British Columbia, to where it intersects Highway 1 (Trans-Canada Highway) just west of Portage la Prairie, Manitoba. It is designated as Highway 16 in all four provinces that it passes through (British Columbia, Alberta, Saskatchewan and Manitoba). It follows a more northerly east–west route across Western Canada than the main TCH and passes through fewer cities, with Edmonton being the largest on the route. Other major municipalities on the route include Prince Rupert, Prince George, Lloydminster and Saskatoon. The Yellowhead Highway is most well known for passing through Jasper National Park in Alberta, where it crosses the Continental Divide through its namesake Yellowhead Pass. Since it carries significantly less traffic than its more southerly counterpart, the Yellowhead is almost exclusively a two-lane highway in British Columbia and Manitoba, and is only partially a four-lane expressway in Alberta and Saskatchewan. Until 1990, the Yellowhead Highway had its own unique highway number signs, but they have now mostly been replaced with standard maple-leaf Trans-Canada Highway signs, with numberless Yellowhead shields posted adjacent to them.

Northern Ontario & Quebec routes

The 1,547 km (961 mi) section of Highway 71 and Highway 11 between Kenora, Ontario, and North Bay, Ontario, is considered part of the Trans-Canada Highway. This highway first runs south of the Main TCH route between Kenora and Thunder Bay, passing through the town of Fort Frances on the U.S. border. Then, after running concurrently with the main Trans-Canada Highway route (Highway 17) it splits off to the north, running through a vast and sparsely-populated area of northern Ontario. This highway sees little long-distance traffic compared to the main route, beside heavy transport trucks looking to avoid the significant elevation changes along the Lake Superior route. Despite being over 100 km (60 miles) longer, it is much flatter and the transit time for heavy hauling is usually the same. The area is also not well known as a tourist destination outside of fishing tours, which are often fly-in. A much shorter 60 km (37 mi) section of Highway 66 connects another northern Trans-Canada Highway route to Quebec's Highway 117, which itself continues the TCH route to Montreal after connecting with Autoroute 15. The main Highway 11 continues south until it intersects the main Trans-Canada Highway route (Highway 17) in North Bay. Except for the southernmost stretches south of Labelle these highways are two-lane undivided routes.

Southern Ontario route

The southern Ontario Trans-Canada Highway route is even more abstract than the northern ones, as it uses four different provincial highways, and is largely non-functional as a major long distance corridor due to its roundabout route and the complete avoidance of the Toronto area. It is a 671 km (417 mile) long alternate route to Highway 17 (the mainline TCH) between Sudbury and Ottawa. It passes through several major communities, including Orillia and Peterborough. Because it passes closer to major population centres, this section of the TCH sees higher traffic volumes. It is made up of various sections of freeways, expressways and two-lane routes.

Prince Edward Island Route

Another spur route of the Trans-Canada Highway splits off the mainline in eastern New Brunswick. This route connects to Prince Edward Island across the 13 km (8 miles) long Confederation Bridge, crosses the central part of Prince Edward Island, including through the provincial capital of Charlottetown, before crossing back to the mainland on a ferry. This length of the route is 234 km (145 miles), and consists of New Brunswick Highway 16, Prince Edward Island Highway 1 and Nova Scotia Highway 106. This leg of the Trans-Canada Highway sees moderately high traffic volumes and is an important tourist route. The Confederation Bridge is often viewed as an attraction in itself. Although the highway is mostly a two-lane route, portions of the route are built as two-lane expressways.

Bypasses

Two short bypasses are also considered part of the Trans-Canada Highway system. These include the 42-kilometre-long (26 mi) Perimeter Highway 100 bypass around Winnipeg, which provides an expressway standard alternative to the crowded Highway 1 in the city centre; and the 34-kilometre-long (21 mi) two-lane Kenora Bypass (Highway 17A) which is a two-lane route that bypasses the entire town to the north.

History

Predecessor routes

Early on, much of the route of the Trans-Canada Highway was first explored in order to construct the Canadian Pacific Railway in the late 19th century, a route which much of the mainline TCH route later ended up following.

The Trans-Canada Highway was not the first road across Canada. In British Columbia, the highway was predated by the Crowsnest Highway, the Big Bend Highway and the Cariboo Highway, all of which were constructed during the Great Depression era. Many of the earlier highways in British Columbia were largely gravel, and had many frequent inland ferry crossings at wide rivers and lakes. In Alberta. the section between Calgary and Banff was predated by the Morley Trail (now Highway 1A). which was drivable starting in the 1910s and paved in the 1930s. The first route over the Central Canadian Rockies to connect Calgary to British Columbia was the Banff–Windermere Parkway, which was opened in 1922 and is now numbered as Highway 93. Sections of road across the Prairies have also existed since the 1920s. A gravel road connection across northern Ontario (Highway 17) was constructed starting in 1931. While this section was largely open by the late 1930s, it was not fully completed until 1951 (in large part due to World War II interrupting construction). However, despite the gap, vehicles could still cross the county by getting ferried around the relatively short section of incomplete highway by either rail or water.

Opening

The system was approved by the Trans-Canada Highway Act of 1949,[20] with construction commencing in 1950.[21] The highway officially opened in 1962, with the completion of the Rogers Pass section of highway between Golden and Revelstoke. This section of highway bypassed the original Big Bend Highway, the last remaining section of gravel highway on the route. Upon its original completion, the Trans-Canada Highway was the longest uninterrupted highway in the world.[22] Construction on other legs continued until 1971 when the last gap on Highway 16 was completed in the Upper Fraser Valley east of Prince George, at which point the highway network was considered complete.

Since completion (1960–2000)

When the Trans-Canada Highway first opened, it was almost exclusively a two-lane route for its whole length across the country. While at the time it was considered a major improvement to the gravel roads and ferries it replaced, it was soon believed to be insufficient to handle the growing traffic volumes. In response, several provinces began to construct realignments, freeway widenings and twin sections of highway in response to traffic flow and safety concerns.

In British Columbia's Lower Mainland, the Upper Levels Freeway alignment was opened in 1960 with the completion of the Second Narrows Crossing, which allowed the Trans-Canada Highway to bypass downtown Vancouver's streets and the narrow Lions Gate Bridge. The four-lane Upper Levels Freeway was relatively-crudely constructed, with narrow lanes, low overpasses and no proper merge ramps. It remains in this state in the present day. Between 1962 and 1964, Highway 1 was rerouted onto a new four-lane freeway bypass between Vancouver and Chilliwack. This section of highway was originally part of British Columbia's own "400" series of highways, until the designation was replaced by Highway 1. A freeway alignment on the Trans-Canada Highway between Chilliwack and Hope opened in 1986. The opening of the Cassiar Tunnel in 1990 bypassed the last sets of signal lights in Vancouver rendering the whole alignment of the Trans-Canada Highway through the Lower Mainland a freeway. All bypassed sections of the highway were absorbed into various urban and rural road networks. The older freeways in the Lower Mainland were largely built as a parkway design, with wide forested medians and low overpasses (a road configuration that was common across North America at the time). The opening of the Coquihalla Highway in 1986 left much of the Trans-Canada Highway through the Fraser Canyon functionally obsolete, with the freeway bypass shortening the drive between Hope and Kamloops by 90 minutes. However, the route was retained as part of the Trans-Canada Highway system, despite being considered nothing more than a scenic route in the present. The opening of the Coquihalla was also an economic disaster for many of the towns along the Fraser Canyon section of the Trans-Canada Highway, since most of the travel and tourism business along the route quickly dried up when most of the traffic took the new highway. The towns continue to be largely deprived of wealth, and some are close to being abandoned. On the other hand. Merritt, located midway up the new Coquihalla highway, ended up booming, and continues to grow as a tourism and travel centre into the present. The Coquihalla project also realigned Highway 1 (TCH) to a new freeway bypass around Kamloops. Plans for a freeway to bypass or eliminate traffic congestion and road hazards along the heavily travelled route from Victoria to Nanaimo on Vancouver Island were cancelled during the recession that followed the 1987 stock market crash.

In Alberta, between 1964 and 1972, the Trans-Canada Highway was completely rerouted from its former two-lane alignment along the Bow River to a new, more direct, four-lane freeway between Banff and Calgary, resulting in the bypassing of several towns, such as Canmore. Prior to this change, one of the first traffic circles in Canada existed on Highway 1 at the "gateway" junction for Banff from at least as early as the 1950s. the current interchange on Highway 1 for Banff Avenue now occupies the site. In the rest of Banff National Park, much of the predecessor Highway 1 parkway was bypassed by a new two-lane route in the 1960s. The original route between Banff and Lake Louise remains as the Bow Valley Parkway and Lake Louise Drive, while a section over Kicking Horse Pass was abandoned and is now part of the Great Divide Trail. Between 1973 and 1990 the highway was twinned from Calgary to the Saskatchewan Border. In 1970 plans were made for a six-to-eight-lane freeway to carry the Trans-Canada Highway though the heart of North Calgary, but the plan was soon dropped due to citizen outcry.

Between Ottawa and the Ontario–Quebec border, the Trans-Canada Highway designation was taken from the two-lane Highway 17 and applied to the existing Highway 417 freeway in 1997–98. On April 1, 1997, the Ministry of Transportation of Ontario (MTO) transferred the responsibility of maintenance and upkeep along 14.2 km (8.8 mi) of Highway 17 east of "the split" with Highway 417 to Trim Road (Regional Road 57) to the Regional Municipality of Ottawa-Carleton, a process commonly referred to as downloading. The Regional Municipality then designated the road as Regional Road 174. Despite the protests of the region that the route served a provincial purpose, a second round of transfers saw Highway 17 within Ottawa downloaded entirely on January 1, 1998, adding an additional 12.8 km (8.0 mi) to the length of Regional Road 174.[23] The highway was also downloaded within the United Counties of Prescott and Russell, where it was redesignated as County Road 17.[24] The result of these transfers was the truncation of Highway 17 at the western end of Highway 417.[25] 1990 saw the opening of the two-lane Kenora Bypass, providing through traffic with a way to avoid the congested town.

Starting in the 1960s, Quebec began to build its Autoroute network. Many sections of Trans-Canada Highway were widened to freeway standards during that era of highway construction.

Starting in 1987, New Brunswick began to widen its section of TCH to 4 lanes. Work to make the route a full freeway began in the late 1990s and was completed in 2007.

The 13 km (8 mile) long Confederation Bridge connecting PEI to New Brunswick opened in 1997. Replacing the ferry that previously serviced that route, it was hailed as a major accomplishment.

Recent changes (2000–present)

In 2000 and 2001, Transport Canada considered funding an infrastructure project to have the full Trans-Canada system converted to limited-access divided highways. Although construction funding was made available to some provinces for portions of the system, the federal government ultimately decided not to pursue a comprehensive limited-access highway conversion. Opposition to funding the limited-access widening was due to low traffic levels on parts of the Trans-Canada Highway.

Prior to the start of the Great Recession in 2008, the highway underwent some changes through the Rocky Mountains from Banff National Park to Golden, British Columbia. A major piece of this project was completed on August 30, 2007, with the new Park Bridge and Ten Mile Hill sections opening up 16 km (9.9 mi) of new four-lane highway. Other smaller four-lane widening projects on the Trans-Canada Highway in the interior of British Columbia were also built around the same time. As part of the Gateway Program, 37 km (23 mi) of congested four-lane Highway 1 freeway in Metro Vancouver were widened to an eight-lane build out starting in 2012. This project continues into the present, with the current goal of rebuilding the freeway to a minimum six-lane layout from Langley to Abbotsford by 2025.

The twinning of the highway in Alberta's Banff National Park continued with four-lane highway opening as far as the Highway 93 junction north of Lake Louise by the winter of 2010. Parks Canada completed twinning the final 8.5 km (5.3 mi) of Highway 1 between Lake Louise and the British Columbia border, with the new alignment opened to traffic on June 12, 2014[26] making the whole length of Alberta's main Trans-Canada Highway route a minimum four lanes. Stoney Trail began construction in 2005, and was usable as a bypass around Calgary when its northeastern section opened in 2010. Although not officially part of the Trans-Canada Highway system, Stoney Trail plays a critical role in providing through traffic on the Trans-Canada Highway with a way around the city.

During the 2000s much of the Trans-Canada Highway through Saskatchewan and Manitoba was twinned. In 2019 the Regina Bypass opened, resulting in the Trans-Canada Highway being realigned around the city, and bypassing a section of heavily-signalized arterial road on Victoria Avenue.

The 2010s saw changes to other routes in the Trans-Canada Highway system as well. Ontario Highway 400 began to be extended towards Sudbury, replacing Highway 69 and resulting in a freeway alignment for part of the Southern Ontario Trans-Canada Highway Route. Work on this project is continuing, with almost 25 km (16 mi) of freeway currently under construction.

Edmonton is currently attempting to widen its urban section of Highway 16 to a six-lane freeway. Large amounts of Highway 16 in Alberta were twinned during the 2000s.

Despite these many widenings, over half of the mainline Trans-Canada highway still remains in its original two-lane state, and only about 15 per cent of the mainline's length is composed of freeway comparable to that of the Interstate Highway System.

In 2012, a series of free public electric vehicle charging stations were installed along the main route of the highway by a private company, Sun Country Highway, permitting electric vehicle travel across the entire length, as demonstrated by the company's president, Kent Rathwell, in a publicity trip from St John's, NL to Victoria, BC in a Tesla Roadster. As of 2012, this made the TCH the longest electric-vehicle-ready highway in the world.[27][28]

Future

No national plan for widening the Trans-Canada Highway exists, and all planning is currently done by the individual provinces. However, as with other routes in Canada's National Highway System, the federal government is required to cost-share for changes funded by the provinces. Currently, there are five large-scale highway projects on the Trans-Canada Highway Network.

Quebec is working on completing Autoroute 85, bringing the last two-lane section of the mainline highway in Quebec up to four-lane freeway standards. As of September 2021, only 7 km (4.3 mi) of two-lane highway had not yet been addressed. The rest either had been completed or was currently under construction.

As of September 2021, Ontario was attempting to extend Highway 400 to Sudbury, which will carry the Southern Ontario TCH designation once complete. Around 80 km (50 mi) of highway remained to be built to freeway standard, with approximately 25 km (16 mi) of new freeway under construction. The project was originally expected to be complete in 2021 but had its date pushed back.

As of September 2021, British Columbia was planning on widening the 420 km (260 mi) long section of TCH between Kamloops and Alberta to four lanes by 2050. The project goals do not include an eventual freeway conversion, and it is likely that the signalized sections of highway in Kamloops, Salmon Arm, Revelstoke and Golden will remain. Around 16 km (9.9 mi) of four-lane highway were under construction, with 6 km (3.7 mi) more planned to start in 2022. Around a quarter of the length of highway between Kamloops and Alberta is now four lanes wide. At the current rate of construction, the project will likely not be completed until the 2070s. However, some of the most difficult sections have been completed, meaning that it may be easier to widen the remaining sections of highway to four lanes. Some of the highway in this section is under the jurisdiction of Parks Canada, specifically the sections through Mount Revelstoke, Glacier and Yoho National Parks, which means that Parks Canada will have to implement its own four-lane program in order for the provincial government to accomplish its goal.

The City of Edmonton is changing its urban section of Highway 16 (TCH) to a six-lane freeway by replacing all signal lights with overpasses. The route is already largely a freeway, but seven signalized intersections remain. The project is expected to be finished by 2026.[29]

As of September 2021, British Columbia was planning on widening 36 km (22 mi) of Highway 1 in the Lower Mainland as part of its Fraser Valley Highway program. The four-lane freeway is over-congested, and many of the overpasses are in poor shape. The project intends to rebuild most of the interchanges and overpasses and widen the highway to six lanes. The first 4 km (2.5 mi) of this project opened in 2020, with 10 km (6.2 mi) more expected to be complete in 2025.

Apart from the major programs, many smaller scale projects exist on the highway in order to either rehabilitate the aging infrastructure or make minor traffic changes.

Alberta had long term plans to convert both of its Trans-Canada Highway routes to a minimum four-lane freeway standard, but has not set a timeline for doing so.

Ontario hopes to eventually extend the 417 freeway to Sudbury, which will carry the mainline TCH route, but it has not set a timeline for doing so.

References

- "Trans-Canada Highway: Bridging the Distance". CBC Digital Archives.

- "Trans-Canada Highway". Unpublished Guides. Library and Archives of Canada. Retrieved July 29, 2011.

- Donaldson MacLeod (2014). "THE TRANS-CANADA HIGHWAY – A Major Link in Canada's Transportation System" (PDF). Conference of the Transportation Association of Canada. Transportation Association of Canada.

- "The world's longest highways". roadtraffic-technology.com. 4 November 2013. Retrieved 17 February 2017.

- "National Highway System" (PDF). Transport Canada. Retrieved April 26, 2014.

- https://www2.gov.bc.ca/gov/content/transportation-projects/highway-1-lower-lynn-improvements

- https://dailyhive.com/vancouver/highway-1-langley-abbotsford-expansion-fraser-valley-design

- Gomez, Michelle (April 15, 2022). "Kicking Horse Canyon stretch of Hwy 1 closing for a month for construction".

- Palmer, Claire (May 20, 2022). "Kicking Horse Canyon to re-open today east of Golden". Maple Ridge-Pitt Meadows News. Kicking Horse Canyon, British Columbia. Retrieved May 29, 2022.

- Google (November 4, 2016). "Highway 1 in Alberta" (Map). Google Maps. Google. Retrieved November 4, 2016.

- Google (November 4, 2016). "Trans-Canada Highway in Saskatchewan and Manitoba" (Map). Google Maps. Google. Retrieved November 4, 2016.

- "Manitoba Trans-Canada Speed Limit Goes Up to 110 km/h Today". CBC Manitoba. 2015. Retrieved June 2, 2015.

- Google (November 4, 2016). "Trans-Canada Highway in Ontario" (Map). Google Maps. Google. Retrieved November 4, 2016.

- "Nipigon River Bridge on Trans-Canada Highway partially reopens". CBC News. Retrieved November 28, 2016.

- "The Montreal River hill: Nine years for nothing?". Northern Ontario Business. May 16, 2006. Retrieved November 17, 2016.

- Google (November 4, 2016). "Trans-Canada Highway in Eastern Canada" (Map). Google Maps. Google. Retrieved November 4, 2016.

- Allen, Paddy (July 11, 2011). "Carmageddon: The World's Busiest Roads". The Guardian. Guardian News & Media Ltd. Archived from the original on July 15, 2014. Retrieved July 11, 2014.

- Muret, Don (April 9, 2001). "Venue's Name Game Takes New Twist". Amusement Business. Retrieved July 30, 2011.

- "The Biggest Mary: Chicken chain Mary Brown's buys naming rights to Mile One Centre". CBC News. October 14, 2021. Retrieved January 9, 2022.

- "Trans-Canada Highway Act". Department of Justice Canada. R.S.C. 1970, c. T-12. Archived from the original on July 25, 2011. Retrieved December 19, 2006.

- "The Trans-Canada Highway". Transport Canada.

- MacLeod, Donaldson (2014). "The Trans-Canada Highway: A Major Link in Canada's Transportation System" (PDF). Transportation Association of Canada. Retrieved March 10, 2016.

- Department of Public Works and Services (September 14, 2004). Responsibilities and Obligations Re: Highway 174 (Report). City of Ottawa. Retrieved February 14, 2011.

- Millier Dickinson Blais (February 16, 2010). "4.2 Linking to the Megaregion". Economic Development Plan – Final Report (Report). Prescott-Russell Community Development Corporation. pp. 41–42. Retrieved March 10, 2011.

- Ontario Road Map (Map). Cartography by Geomatics Office. Ministry of Transportation. 1999.

- Schmidt, Colleen (June 13, 2014). "Crews Complete Twinning of Trans-Canada Through Banff National Park". CTV Calgary. Retrieved June 13, 2014.

- Caulfield, Jane (December 11, 2012). "Electrifying Trip Along the Trans-Canada Highway Pit Stops in Saskatchewan". Metro. Archived from the original on December 16, 2013. Retrieved April 12, 2014.

- "World's Longest Greenest Highway Project: Item Details". Sun Country Highway. Retrieved July 11, 2019.

- "Yellowhead Trail Freeway Conversion - Program History | City of Edmonton". www.edmonton.ca. Retrieved February 14, 2022.

External links

- Trans-canada highway.com—Detailed province by province description, history, and itineraries

- Dirt Roads to Freeways ... And All That, c. 1970s, Archives of Ontario YouTube Channel

- Ten Mile Hill Project Trans-Canada in B.C. HD Video

- Trans-Canada Road Trip—Details, blog and photographs from a road trip on the TCH coast to coast in 2018