Ontario Highway 11

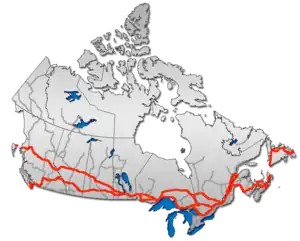

King's Highway 11, commonly referred to as Highway 11, is a provincially maintained highway in the Canadian province of Ontario. At 1,784.9 kilometres (1,109.1 mi), it is the second longest highway in the province, following Highway 17. Highway 11 begins at Highway 400 in Barrie, and arches through northern Ontario to the Ontario–Minnesota border at Rainy River via Thunder Bay; the road continues as Minnesota State Highway 72 across the Baudette–Rainy River International Bridge. North and west of North Bay (as well as for a short distance through Orillia), Highway 11 forms part of the Trans-Canada Highway. The highway is also part of MOM's Way between Thunder Bay and Rainy River.

The original section of Highway 11 along Yonge Street was colloquially known as "Main Street Ontario", and was one of the first roads in what would later become Ontario. It was devised as an overland military route between York (Toronto) and Penetanguishene. Yonge Street serves as the east–west divide throughout York Region and Toronto.

Highway 11 became a provincial highway in 1920 when the network was formed, although many of the roads that make up the route were constructed before the highway was designated. At the time, it only extended between Toronto and north of Orillia. In 1937, the route was extended to Hearst, northwest of Timmins. The route was extended to Nipigon by 1943. In 1965, Highway 11 was extended to Rainy River, bringing it to its maximum length of 1,882.2 kilometres (1,169.5 mi). The southernmost leg, an 86-kilometre (53 mi) section (including the Bradford–Barrie extension) through Barrie and south to Lake Ontario in Toronto, also known as Yonge Street, was decommissioned as a provincial highway in 1996 and 1997.

From the late 1940s through the 1960s, numerous bypasses of towns along the route were built, including Orillia, Washago, Gravenhurst, Bracebridge, Huntsville, Emsdale, Powassan, Callander, North Bay, Cobalt, Haileybury, New Liskeard and Thunder Bay. Beginning in the 1960s, the highway was four-laned between Barrie and North Bay in stages. Four laning was completed between Barrie and Gravenhurst in the 1960s, between Gravenhurst and Huntsville in the 1970s, and from North Bay south to Callandar in the 1980s. The remaining two lane section between Huntsville and Callander was four laned through the 1990s and 2000s, and was completed in 2012. A section concurrent with Highway 17 east of Thunder Bay was rebuilt as a divided highway in the early 2010s and work continues. The two-lane Nipigon River Bridge was replaced with a twin-span bridge that opened in 2018, following a structural failure in 2016.

Route description

Highway 11 varies between a divided four-lane urban freeway and a two-lane rural road. It travels through surroundings ranging from cities to farmland to the uninhabited wilderness. The section through northern Ontario includes several sections with no gas or service for over 160 kilometres (100 mi). Significant urban centres serviced by the route include Barrie, Orillia, Gravenhurst, Bracebridge, Huntsville, North Bay, Temiskaming Shores, Cochrane, Kapuskasing, Hearst, Nipigon, Thunder Bay, Atikokan, Fort Frances and Rainy River.[1][2] It is often paired with Yonge Street in the persistent but incorrect factoid that Yonge Street is the longest street in the world, a claim that was featured in the book of Guinness World Records from 1977 to 1998.[3][4][5]

Barrie – North Bay

Highway 11 begins at an interchange with Highway 400 on the north side of Barrie, travelling northeast parallel to the northwestern shore of Lake Simcoe. The four-lane route, divided by a median barrier, crosses former Highway 93 (Penetanguishene Road) and passes through a generally flat rural area, though businesses line both sides of the route. At the northern end of Lake Simcoe, the highway enters Orillia, where it is built as a divided freeway. It meets and becomes concurrent with Highway 12 for 2.4 kilometres (1.5 mi). At Laclie Drive, the route exits Orillia and returns to a RIRO design with rural surroundings. It travels northward along the western shore of Lake Couchiching as far as Washago, then crosses the Severn River / Trent Severn Waterway.[1][2]

North of the Severn River, Highway 11 travels through the Canadian Shield; large granite outcroppings are frequent and thick Boreal forest dominates the terrain.[2] At Gravenhurst, the highway makes a sharp curve to the east, then becomes a divided freeway before curving northward around Gull Lake. Near Bracebridge, it meets Highway 118 and former Highway 117. Highway 141 branches west from the route between Bracebridge and Huntsville, while Highway 60 branches east towards Algonquin Park in Huntsville. The section between Gravenhurst and Bracebridge is at freeway standards, while several at-grade intersections remain between Bracebridge and Huntsville.[1][2] Highway 11 crosses the 45th parallel north 550 metres (1,800 ft) north of the bridge carrying Highway 118 at interchange 182, just outside Bracebridge.[6]

The 120-kilometre (70 mi) section of Highway 11 between Huntsville and North Bay provides access to the western side of Algonquin Park. It also connects to Highway 518 at Emsdale, Highway 520 at Burk's Falls, Highway 124 at Sundridge and South River, Highway 522 at Trout Creek, Highway 534 at Powassan, and Highway 94 and Highway 654 at Callander. Most of this section is built to freeway standards, although a small number of at-grade intersections remain, primarily between Trout Creek and Callander.[1][2]

North Bay – Nipigon

From its junction with Highway 17 at North Bay, the two highways share a concurrency for 4.1 kilometres (2.5 mi) to the Algonquin Avenue intersection, where Highway 17 continues west toward Sudbury and Sault Ste. Marie while Highway 11 turns north onto Algonquin Avenue.[1][2] Due to a steep incline as it descends Thibeault Hill into North Bay, the southbound Algonquin Avenue segment of Highway 11 features the only runaway truck ramp on Ontario's highway system, which was upgraded in 2009.[7] From North Bay, Highway 11 extends northerly for 370 kilometres (230 mi), passing through communities such as Temagami, Latchford, Temiskaming Shores, Englehart and Matheson en route to Cochrane, where the route turns west. From Cochrane, it passes through communities such as Smooth Rock Falls, Kapuskasing, Hearst and Greenstone, arching across northeastern Ontario westward then south for 613 kilometres (381 mi) before again meeting Highway 17 at Nipigon.[1][2]

Nipigon – Rainy River

Nearly the entire route from Nipigon to Rainy River is a two-lane, undivided road, with the exception of two twinned, four-lane segments approaching Thunder Bay. The first starts just west of Nipigon and ends just north of the Black Sturgeon River, for a distance of 10 kilometres (6.2 mi). The second portion reaches a distance of 36 kilometres (22 mi), from Highway 587 at Pass Lake to Balsam Street in Thunder Bay. Work is being done to twin the route from Ouimet to Dorion.[8] Additionally, the section from Balsam Street to the Harbour Expressway is four lanes wide, but undivided. The partial cloverleaf interchange at Thunder Bay's Hodder Avenue is the only interchange in Northwestern Ontario.[1][2]

Highway 11 and 17 run concurrently from Nipigon down to Thunder Bay, a distance of approximately 90 kilometres (56 mi), where they swing west on the Shabaqua Highway, encountering Kakabeka Falls several kilometers later. The highway then runs in a northwestern direction to Shabaqua Corners, where the two highways split; Highway 17 continues northwest to Dryden and Kenora, while Highway 11 continues in a generally west direction, eventually reaching Highway 11B at Atikokan, approximately halfway between Thunder Bay and Rainy River. The highway continues for 132 kilometres (82 mi), crosses the Noden Causeway, and reaches Fort Frances, where Highway 71 runs south across the U.S. border to International Falls. From here, Highway 11 shares a concurrency with Highway 71 for 37 kilometres (23 mi) until the latter branches north after Emo, while Highway 11 runs parallel to the border for 51 kilometres (32 mi) before ending at the town of Rainy River, where the roadway continues into Baudette, Minnesota, and ends at Minnesota State Route 11.[1][2]

Business routes

Highway 11B is the designation for business routes of Highway 11, ten of which have existed over the years. Two continue to exist today, while the remaining eight have been decommissioned. With the exception of the short spur route into Atikokan, all were once the route of Highway 11 prior to the completion of a bypass alignment. All sections of Highway 11B have now been decommissioned by the province with the exception of the Atikokan route and the southernmost section of the former Tri-Town route between Cobalt and Highway 11.[1]

History

Predecessors

The earliest established section of Highway 11 is Yonge Street in Toronto and York Region, though it is no longer under provincial jurisdiction. Yonge Street was built under the order of the first Lieutenant-Governor of Upper Canada (now Ontario), John Graves Simcoe. Fearing imminent attack by the United States, he sought to create a military route between York (now Toronto) and Lake Simcoe. In doing so, he would create an alternative means of reaching the upper Great Lakes and the trading post at Michilimackinac, bypassing the American border.[9]

In late 1793, Simcoe determined the route of his new road. The following spring, he instructed Deputy Surveyor General Augustus Jones to blaze a small trail marking the route.[10] Simcoe initiated construction of the road by granting land to settlers, who in exchange were required to clear 33 feet (10 m) of frontage on the road passing their lot.[11] In the summer of 1794, William Berczy was the first to take up the offer, leading a group of 64 families north-east of Toronto to found the town of German Mills, in today's Markham. By the end of 1794, Berczy's settlers had cleared the route around Thornhill. However, the settlement was hit by a series of setbacks and road construction stalled.[9]

Work on the road resumed in 1795 when the Queen's Rangers took over. They began their work at Eglinton Avenue and proceeded north, reaching the site of St. Albans on February 16, 1796. Expansion of the trail into a road was a condition of settlement for farmers along the route, who were required to spend 12 days a year to clear the road of logs, subsequently removed by convicted drunks as part of their sentence. The southern end of the road was in use in the first decade of the 19th century, and became passable all the way to the northern end in 1816.[12]

For several years the Holland River and Lake Simcoe provided the only means of transportation; Holland Landing was the northern terminus of Yonge Street. The military route to Georgian Bay prior to, and during the War of 1812, crossed Lake Simcoe to the head of Kempenfelt Bay, then by the Nine Mile Portage to Willow Creek and the Nottawasaga River. The Penetanguishene Military Post was started before the war. However, lacking a suitable overland transport route, passage from York to Lake Huron continued via the Nottawasaga. The Penetanguishene Road, begun in 1814, replaced this route by the time the military post was opened in 1817.[13]

In 1824, work began to extend Yonge Street to Kempenfelt Bay near Barrie. A north-western extension was branched off the original Yonge Street in Holland Landing and ran into the new settlement of Bradford before turning north towards Barrie. Work was completed by 1827, making connections with the Penetanguishene Road. A network of colonization roads built in the 1830s (some with military strategy in mind) pushed settlement northeast along the shores of Lake Simcoe and north towards the shores of Georgian Bay.[14] Construction of the Muskoka Road began by the 1860s. The road, which penetrated the southern skirts of the Canadian Shield and advanced towards Lake Nipissing, reached as far as Bracebridge by 1861, and to Huntsville by 1863.[15] It was officially opened when it reached Lake Nipissing in 1874.[16] Further extensions into Northern Ontario would await the arrival of the automobile, and consequent need for highway networks.

Assumption and paving

Highway 11 was initially planned as a trunk road to connect the communities of Southern Ontario to those of Northern Ontario, as a continuous route from Toronto to North Bay. In 1919, Premier of Ontario Ernest Charles Drury created the Department of Public Highways (DPHO), though much of the responsibility for establishing the route he left to minister of the new cabinet position, Frank Campbell Biggs. By linking together several previously built roads such as Yonge Street, Penetanguishene Road, Middle Crossroad and the Muskoka Road—all early colonization roads in the region—a continuous route was created between Toronto and North Bay; however, the new department's jurisdiction did not extend north of the Severn River. Roads north of that point were maintained by the Department of Northern Development (DND).[17]

In order to be eligible for federal funding, the DPHO established a network of provincial highways on February 26, 1920.[18] What would become Highway 11 was routed along Yonge Street, its extension to the Penetanguishene Road, and the Muskoka Road as far as the Severn River.[19] The portions of Yonge Street through what is now York Region, as well as Toronto as far south as Yonge Boulevard, were assumed by the DPHO on June 24, 1920, while the portions through Simcoe County, from Bradford to Severn Bridge were assumed two months later on August 18.[20] It received its numerical designation in the summer of 1925.[21]

The new route was mostly unpaved, with work beginning in 1922 to improve the roadway. That year saw paving completed between Yonge Boulevard and Thornhill, as well as a bypass of the original route through Holland Landing (now known as York Regional Road 83).[22] The pavement was extended farther north from Thornhill to Richmond Hill the following year.[23] By 1925, the route was paved from Toronto north to Fennell, as well as between Orillia and Washago.[24] An additional 5 kilometres (3 mi) north from Fennell were paved in 1926. In 1927, the pavement between Toronto and Barrie was completed with the paving of approximately 16 kilometres (10 mi) south from Barrie.[25] Between Barrie and Orillia, paving began in 1929, with the completion of approximately 13 kilometres (8 mi) east from Guthrie; at that point the highway turned north at 11th Line, then east at East Oro along Sideroad 15/16. That year also saw paving completed from Washago to north of Gravenhurst.[26][27] The following year, the newly-renamed Department of Highways (DHO) paved the remaining 13 kilometres between Barrie and Guthrie,[28] while the DND paved the Muskoka Road from Gravenhurst to Huntsville.[29] The final 7.6 kilometres (4.7 mi) of unpaved road between Barrie and Orillia was completed in 1931.[28]

Ferguson Highway and extension to Nipigon

Throughout the 1910s and early 1920s, various chambers of commerce, rotary clubs and boards of trade petitioned the government to construct a new trunk road from North Bay towards the mining communities to the north that were established in the prior decades.[30][31][32][33] These delegations and committees also saw the potential tourist draw of opening the Temagami area to hunters, fishers, and recreational tourism.[34] By 1923, a road existed between Cobalt and Kirkland Lake, as well as between Ramore and Cochrane, with an approximately 32-kilometre (20 mi) gap separating the two sections.[35][36] Conservative leader Howard Ferguson promised to build a road to connect North Bay and Cochrane during the 1923 Ontario general election, which saw him elected as premier.[37]

The route of the new road between North Bay and Cobalt was cleared by April 1925,[38] after which construction began in August from both North Bay as well as Cobalt.[39] The new gravel highway was officially opened on July 2, 1927,[37] by Minister of Lands and Forests William Finlayson. He suggested at the opening that the road be named the Ferguson Highway in honour of premier Ferguson. The name was originally suggested by North Bay mayor Dan Barker.[40] Despite the official opening, a section between Swastika and Ramore wasn't opened until August.[41] The Ferguson Highway name was also applied to the Muskoka Road between Severn Bridge and North Bay.[37] Although the route from North Bay to Cochrane was passable, it was not an adequate road in many places. Construction continued for several years to build bypasses of sharp turns, steep grades, awkward rail crossings, and other obstacles. The Ferguson Highway was extended from Cochrane to Kapuskasing by 1930, and later to Hearst in 1932.[42][43]

The Provincial Highway Network was radically overhauled in 1937, when the DND merged with the DHO on April 1. Consequently, the DHO assumed responsibility of roads north of the Trent–Severn Waterway over the next several months.[44] On June 2, 339.2 kilometres (210.8 mi) of the Ferguson Highway was assumed by the DHO through Cochrane District. This was followed one week later when 80.5 kilometres (50.0 mi) of the Muskoka Road through the District of Muskoka were assumed on June 9. A 96.7 kilometres (60.1 mi) portion of the route, which included a portion of what is now Highway 94 to connect to the Dionne quintuplets, was assumed through Parry Sound District on June 16. On June 30, 136.9 kilometres (85.1 mi) of the Ferguson Highway were assumed north of North Bay within Nipissing District, as well as 182.1 kilometres (113.2 mi) through Timiskaming District. Highway 11 grew in length from 154.2 kilometres (95.8 mi) to 1,024.0 kilometres (636.3 mi).[45][46]

Construction began in 1938 on a road to connect Highway 17 at Nipigon with the gold mines discovered near the town of Geraldton several years earlier.[47][48] Although portions of this new road were passable by the end of 1939,[49] the Nipigon–Geraldton Highway was opened ceremoniously by Thomas McQuesten and C. D. Howe on September 7, 1940;[50] it was assumed as a provincial highway in 1941.[51] With the onset of World War II, the need for an east–west connection across Canada became imperative,[52] and construction began on a link between Geraldton and Hearst, a distance of 247 kilometres (153 mi) in 1939. Due to the shortage of labour, several prison camps were established between the two communities in October of that year and work began to clear a tote road for the movement of supplies over the following winter.[53][54] While the highway was completed in November 1942, it was not maintained during through the winter, and the official opening did not take place until June 12, 1943.[55] Following this, Highway 11 was extended to Nipigon, and was 1,421.1 kilometres (883.0 mi) long.[56]

Thunder Bay – Rainy River

Highway 11 ended at Nipigon until the late 1950s, after construction of a new highway west from Thunder Bay towards Fort Frances began. During World War II, large deposits of iron ore were discovered at Steep Rock Lake, around which the town of Atikokan was developed.[57] The need to connect the burgeoning community to the road network became apparent following a rail strike in August 1950, during which a "mercy train" was delivered to the isolated town. Throughout the fall of 1950, various delegates pressed the provincial government to construct a road link immediately.[58][59][60] The province announced plans for the new highway between Atikokan and Shebandowan the following August,[61] and released the proposed route on October 10; construction began shortly thereafter.[62][63] The Atikokan Highway was ceremonially opened by premier Leslie Frost on August 13, 1954, although traffic had used the incomplete road beginning in November 1953. At that event, which saw him use an axe to cut a ribbon, Frost announced the future vision to extend the new route to Fort Frances. Despite the opening, work was ongoing to improve the existing road between the end of the new highway at Shebandowan and Highway 17 at Shabaqua Corners.[64][65]

Initially this road was designated as Highway 120. In 1959, it was decided to make this new link a westward extension of Highway 11. On April 1, 1960, Highway 11 assumed the route of Highway 120; this consequently created a concurrency of Highway 11 and 17 between Nipigon and west of Thunder Bay.[66][67][68] Now reaching as far as Atikokan, construction of a road between there and Fort Frances was carried out over the next five years. The final link, the 5.6-kilometre (3.5 mi) Noden Causeway over Rainy Lake, was opened on June 28, 1965, after which Highway 11 was extended to Rainy River and the American border.[69] Highway 11 was now at its peak length of 1,882.2 kilometres (1,169.5 mi).[70]

Lakehead Expressway

In 1963, Charles MacNaughton, minister of the Department of Highways, announced plans for the Lakehead Expressway to be built on the western edge of the twin cities of Port Arthur and Fort William (which amalgamated in 1970 to form Thunder Bay).[71] Plans called for a 28.2 kilometres (17.5 mi) at-grade expressway from South of Arthur Street to meet Highway 11 and Highway 17 northeast of the cities.[72] Work began in August 1965, with a contract for a 5 kilometres (3 mi) section of divided highway on the west side of the twin cities.[73] The first section of the expressway opened on August 29, 1967, connecting Oliver Road (then part of Highway 130) and Golf Links Road with Dawson Road (Highway 102).[74] By mid- to late 1969, the route had been extended to Highway 527 northeast of the twin cities and to Highway 11 and Highway 17 (Arthur Street) at the Harbour Expressway.[75] By late 1970, the route had been extended southward from Arthur Street to Neebing Avenue / Walsh Street West. At this time, Highway 11 and 17 and Highway 61 were rerouted along the completed expressway. The old routes through Thunder Bay were redesignated as Highway 11B/17B and Highway 61B.[76][77][78]

Expansion and rerouting

While Highway 11 was extended farther north and west between the 1920s and 1960s, numerous projects took place along the sections between Barrie and Cochrane during that period to either realign the highway to improve the geometry, or to bypass built up areas. The largest bottleneck along the highway in the 1940s was between Washago and through Gravenhurst, where construction began in 1947 to realign 23 kilometres (14 mi) between the two towns, including a new high-level bridge over the Trent–Severn Waterway.[79][80] The original bypass of Gravenhurst, along what is now Bethune Drive, opened in 1948,[81] while reconstruction of the remainder of the route between Washago and Gravenhurst was completed in 1949.[80]

To the south, improvements between Barrie and Orillia, including a divided four-lane highway around the latter, were completed by 1955.[82] During that period, a two-lane bypass around Washago was built between 1954 and 1955.[82][83] Similar bypasses were built between Barrie and North Bay over the next decade, which were later incorporated into the modern four-lane route. A bypass of Bracebridge opened July 1, 1953.[84] The North Bay bypass was completed in 1953,[85] while bypasses of Emsdale and Powassan were completed 1956[86] and 1957, respectively. Construction of the Huntsville Bypass began in 1957;[87] it opened November 27, 1959.[88] The original Callander Bypass, which is now divided into Callander Bay Drive and part of Highway 93, also opened in October 1959.[89] Further north, the 19-kilometre (12 mi) Tri-Town Bypass, from Gillies to north of New Liskeard, was opened on September 18. The new route bypassed the towns of Cobalt, Haileybury and New Liskeard (the latter two which have since become part of Temiskaming Shores).[90] In several cases, the original route of Highway 11 became a business route (Highway 11B, see #Business routes) upon the completion of a bypass.

Beginning in 1965[91][92] Highway 11 was widened to a divided four-lane route between Orillia and North Bay. Initially, this work began at the southern end and progressed northwards; work later began southwards from North Bay.[93] The first section to be four-laned was 8.0 kilometres (5.0 mi) north of Orillia, which was completed in October 1964, while the remaining 5.6 kilometres (3.5 mi) north to Severn River was completed by the end of 1965.[94] Construction continued north of Severn River, with a 7.1-kilometre (4.4 mi) section—including a second bridge over the Severn River—opening as far north as Kahshe Lake in October 1966. Construction on the next 8.6 kilometres (5.3 mi) from Kahshe Lake to south of Gravenhurst began that year.[95] The current 6.8-kilometre (4.2 mi) bypass of Gravenhurst, crossing Gull Lake, was announced on March 31, 1966,[96][97] and construction began in the spring of 1967.[81][98] The new bypass was completed and opened in late 1970.[99]

By 1971, Highway 11 was a four lane divided highway from Orillia to the northern interchange with Bethune Drive in Gravenhurst, and work was underway on twinning the highway between Gravenhurst and then-Highway 117 (now Highway 118), north of Bracebridge;[100][101] That project was completed by 1974.[102] Between then and 1979, widening was completed to 7.4 kilometres (4.6 mi) north of Highway 141 at Stephenson Road 12 along the existing route of Highway 11, and underway for another 4.3 kilometres (2.7 mi) to the southern end of the Huntsville Bypass.[103]

Downloading and four-laning Huntsville to Powassan

In 1996 and 1997, the care (or rescinding of Connecting Link agreements) of Highway 11 from Barrie southwards, including all of Yonge Street, was transferred by the provincial government to county, regional, and city governments by the Ministry of Transportation of Ontario as part of the Mike Harris government's Common Sense Revolution. This practice is called downloading, in that the financial burden will fall to a lower tier government. The entire 36 kilometres (22 mi) of Highway 11 within York Region was transferred to the region on April 1, 1996.[104] This was followed up a year later with the transfer of 27.3 kilometres (17.0 mi) of the highway within Simcoe County south of Crown Hill on April 1, 1997.[105] Along with the name Yonge Street, the section in York Region is now York Regional Road 1, while the section in Simcoe County is now mostly Simcoe County Road 4. Within the city of Toronto, which does not have a road numbering system, it is known as Yonge Street.[106]

By 1997, the four-laning of Highway 11 reached to approximately 2.5 kilometres (1.6 mi) north of Highway 60,[107] where an interchange was built in 1992,[108] as well as from North Bay south to Powassan.[107] A continuous construction project was carried out over the next 15 years to widen the remaining 93 kilometres (58 mi) between Huntsville and Powassan.[109][110] A 7-kilometre (4.3 mi) project to twin the existing two lane highway between Powassan and McGillvray Creek opened in September 1997. This was followed in October 1999 with the opening of another 5-kilometre (3.1 mi) of twinning from McGillvray Creek south to Hummel Line, north of Trout Creek.[111]

In the early 2000s, several more sections were completed at both the north and south end of the remaining two lane highway. A 4-kilometre (2.5 mi) section was opened in September 2001 north of the Huntsville Bypass to south of Novar, mostly along a new alignment alongside the existing highway. On October 3, 2002, the southbound lanes of the 7-kilometre (4.3 mi) Trout Creek Bypass, a new alignment around that town, were opened, followed by the northbound lanes two weeks later. An additional 13-kilometre (8.1 mi) of twinning was completed by the end of that year between Novar and south of Emsdale.[111]

In 2003, a major failure of the Sgt. Aubrey Cosens VC Memorial Bridge at the Montreal River in Latchford caused a complete closure and significant detour.[112] A temporary one-lane Bailey bridge, which opened two weeks after the incident, was constructed to carry traffic on the highway;[113] due to the expected water levels on the Montreal River once ice and snow began to melt in the spring, however, a second temporary bridge then had to be constructed for the duration of the original bridge's reconstruction.[114] According to the Ministry of Transportation's final report, the failure was caused by a fatigue fracture of three steel hanger rods on the northwest side of the bridge.[115] Following reconstruction, the bridge resumed service in 2005. Each hanger rod was replaced with four cable wires, to provide greater stability in the event of a wire failure.[116]

On October 30, 2004, another 10 kilometres (6.2 mi) of four-laning was opened between the south end of the Trout Creek Bypass and north of South River.[117] To the south, a 6-kilometre (3.7 mi) bypass of Emsdale opened the week of October 21, 2005, with a portion of the original Emsdale Bypass (constructed in 1956)[86] remaining as Highway 518.[118] This left a 41-kilometre (25 mi) gap remaining to be four-laned; by 2009, construction was underway on 36 kilometres (22 mi).[119] A 7.5-kilometre (4.7 mi) section from south of Burk's Falls to south of Katrine was four-laned by late 2010, mostly along a new alignment. The 17-kilometre (11 mi) Sundridge–South River Bypass opened to traffic on or about September 20, 2011, along a new alignment.[120] The final two projects, twinning the Burk's Falls Bypass and a new alignment alongside the existing highway between Burk's Falls and Sundridge, were completed and opened together on August 8, 2012, completing the four laning between Barrie and North Bay. Overall, the project between Huntsville and Powassan required "16 new interchanges, 54 new bridges, 1.7 million cubic meters of rock excavation, 10.5 million cubic metres of earth excavation, 4.6 million tonnes of granular material applied and 500,000 tonnes of asphalt."[109]

Since 2010

Plans for four-laning Highway 11/17 from the end of the Thunder Bay Expressway northwest to Nipigon, including the Nipigon River Bridge, were first announced in December 1989.[121] The corridor was divided into four segments, and an Environmental Study Report (ESR) was published for each in 1996 or 1997.[122][123] While the MTO designated the corridor—a mix of twinning the existing highway and a new alignment—in 2003,[123] funding wasn't committed to the project until the late 2000s. In early-to-mid 2009, the provincial government announced the first of several contracts to expand the highway, starting from the Thunder Bay end. Construction on the 4.4-kilometre (2.7 mi), $42-million contract began in August 2010, from west of Hodder Avenue to Highway 527.[124] The westbound lanes opened the weekend of August 6, 2011;[125] the existing highway was then rebuilt as the eastbound lanes, and opened on August 17, 2012. An interchange at Hodder Avenue—the first in Northwestern Ontario—was included as part of this project[126]

By 2012, construction was already underway on two more contracts: A $46-million project to twin 12.3 kilometres (7.6 mi) of the existing highway between Highway 527 and west of Mackenzie Station Road that began in 2010,[127] and another 12.3-kilometre project built along a new alignment east of that point to Birch Beach Road. The latter project was completed first, opening in July 2013,[126][128] while the former was opened the week of September 29, 2014.[129]

Construction began in 2013 on a new four lane cable-stayed bridge across the Nipigon River, to replace the existing two lane bridge built in 1974.[130] The southern span to carry the future westbound lanes was opened on November 28, 2015, after which the old bridge closed. It was subsequently demolished to allow the construction of the northern span to carry eastbound traffic, which was scheduled for 2017.[131][132] However, on January 10, 2016, the bridge experienced a significant structural failure in which the deck raised 60 centimetres (2 ft), severing the only highway connection between eastern and western Canada.[133] A single lane was reopened the following day and repairs began; both lanes were reopened on February 25, 2016.[134] The failure caused a significant delay in the construction of the northern span, which did not open until November 23, 2018,[135] The 2.5 kilometres (1.6 mi) of approaches at each end were completed in 2019.[126]

On June 10, 2015, the province announced the awarding of two contracts: A $32.7 million contract awarded to twin 5.7 kilometres (3.5 mi) of the existing highway from Birch Beach Road to Highway 587 near Loon, and an $84.8 million contract to construct a new 9.7-kilometre (6.0 mi) alignment from Red Rock Road No. 9 to Stillwater Creek near Nipigon.[136] Construction began on the former in October,[137] and on the latter by the end of June.[137] The section from Birch Beach Road to Highway 587 was completed on September 1, 2017,[138][139] while the section from Red Rock Road No. 9 to Stillwater Creek was completed in September 2019.[139]

On March 29, 2022, the Government of Ontario announced that it was extending its 110-kilometre-per-hour (68 mph) speed limit increase, on a trial basis, to the section of Highway 11 from north of Katrine to north of South River.[140][141]

Future

Work is ongoing or upcoming to twin or realign the remaining 55 kilometres (34 mi) of two-laned Highway 11/17 between Thunder Bay and Nipigon. On December 8, 2020, a $71-million contract was awarded for a mix of twinning and a new alignment for 7.9-kilometre (4.9 mi) from Superior Shores Road south of Ouimet to south of Dorion Loop Road near Dorion. Construction started a few weeks earlier at the end of November. The project is scheduled for completion in September 2023.[142] On July 11, 2022, 4 kilometres (2.5 mi) of the new eastbound lanes opened from Ouimet Canyon Road to Superior Shores Road. The remainder of the eastbound lanes, from Ouimet Canyon Road to Dorion Loop Road, are scheduled to open by the end of the year.[8]

On April 9, 2022, the province announced a $107-million contract to twin and realign 13.2 kilometres (8.2 mi) of Highway 11/17 from the end of the existing four lane route near Highway 587 to Pearl. Construction is scheduled to begin in late 2022 and be completed in 2026.[143]

The remaining 34 kilometres (21 mi)[144] are in the detailed design process as of 2022, and are broken up into several sections: 6.6 kilometres (4.1 mi) between Pearl and south of Ouimet; 10.3 kilometres (6.4 mi) between Dorion Loop Road and near Highway 582; 8.3 kilometres (5.2 mi) between Highway 582 and Coughlin Road; 4.7 kilometres (2.9 mi) between Coughlin Road and Red Rock Road No. 9, crossing the Black Sturgeon River and connecting with the existing four lane route, and; 4.2 kilometres (2.6 mi) through Nipigon, between Stillwater Creek and First Street.[126][137]

Highway 11 between Barrie and Gravenhurst is currently a right-in/right-out (RIRO) expressway (local access permitted, turnarounds via special interchanges), except for a section around Orillia which is a full freeway. Another freeway section (formerly Highway 400A) does exist in Barrie with the freeway segment from the southern terminus ending at Penetanguishene Road (Simcoe County Road 93). The MTO is currently planning on either converting the existing RIRO expressway to a full six-lane freeway or bypassing it with an entirely new alignment. An environmental and fiscal study concluded that the improvements from Barrie to Gravenhurst will involve the existing route being widened with the exception of a portion south of Gravenhurst that may potentially be constructed to the east of the current road.[145]

Major intersections

The following table lists the major junctions along Highway 11, as noted by the Ministry of Transportation of Ontario.[1] Interchanges are numbered between Barrie and North Bay.

| Division | Location | km[1] | mi | Exit | Destinations | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Metropolitan Toronto | Toronto (Old) | −100.5 | −62.4 | Lake Shore Boulevard | ||

| −98.9 | −61.5 | King Street | ||||

| −98.0 | −60.9 | Dundas Street | ||||

| −96.4 | −59.9 | |||||

| −92.2 | −57.3 | Eglinton Avenue | ||||

| North York | −87.0 | −54.1 | ||||

| −86.0 | −53.4 | Sheppard Avenue | ||||

| Metropolitan Toronto-York boundary | North York-Vaughan-Markham | −81.9 | −50.9 | Steeles Avenue | Highway 11 is signed as York Regional Road 1 | |

| York | Thornhill | −77.8 | −48.3 | |||

| −77.3 | −48.0 | Highway 7 was downloaded to the York Region in 1998; currently York Regional Road 7 | ||||

| Richmond Hill | −73.7 | −45.8 | ||||

| Aurora | −59.2 | −36.8 | ||||

| Newmarket | −53.0 | −32.9 | Highway 9 was downloaded to the Region of York in 1998; currently York Regional Road 31 | |||

| East Gwillimbury | −49.9 | −31.0 | Yonge Street turned off Highway 11 | |||

| −46.2 | −28.7 | |||||

| Simcoe | Bradford | −42.3 | −26.3 | Highway 88 was downloaded to Simcoe County in 1998. Currently Simcoe County Road 88. | ||

| −40.9 | −25.4 | Line 8 | Highway 11 is currently Simcoe County Road 4 between Bradford and Barrie. Yonge Street (extension) rejoined Highway 11 | |||

| Bradford-West Gwillimbury | −30.9 | −19.2 | Highway 89 was downloaded to Simcoe County in 1998; currently | |||

| Innisfil | −21.2 | −13.2 | ||||

| Barrie | −15.7 | −9.8 | Mapleview Drive | |||

| −9.7 | −6.0 | Beginning of former Highway 27 concurrency | ||||

| −7.5 | −4.7 | End of former Highway 27 concurrency. | ||||

| Simcoe | Oro-Medonte | 0.0 | 0.0 | Current southern terminus of Highway 11. The highway followed Penetanguishene Road southwards prior to downloading, and the first 1.1 km was formerly the unsigned Highway 400A[2][1] | ||

| 1.1 | 0.68 | Formerly Highway 93; continuation of Ontario Highway 400 kilometre markers[2] | ||||

| 5.7 | 3.5 | Oro-Medonte Line 4 | ||||

| 15.8 | 9.8 | |||||

| Orillia | 23.6 | 14.7 | 129 | Memorial Avenue | Northbound exit only; southbound exit and northbound entrance via Oro-Medonte Line 15 | |

| 25.3 | 15.7 | 131 | South end of Highway 12 concurrency | |||

| 27.7 | 17.2 | 133 | North end of Highway 12 concurrency | |||

| 29.8 | 18.5 | 135 | ||||

| 31.4 | 19.5 | Laclie Street | Northbound entrance and southbound exit | |||

| Simcoe | Severn | 38.9 | 24.2 | Bayou Road / New Brailey Line | ||

| 46.7 | 29.0 | |||||

| 49.0 | 30.4 | Severn River bridge | ||||

| Muskoka | Gravenhurst | |||||

| 64.9 | 40.3 | 169 | Dead Man's Curve; no northbound entrance | |||

| 69.9 | 43.4 | 175 | ||||

| 76.8 | 47.7 | 182 | ||||

| Bracebridge | ||||||

| 78.8 | 49.0 | 184 | ||||

| 83.6 | 51.9 | 189 | ||||

| 87.5 | 54.4 | 193 | ||||

| Huntsville | 101.8 | 63.3 | 207 | |||

| 114.3 | 71.0 | 219 | Huntsville Bypass | |||

| 116.6 | 72.5 | 221 | ||||

| 118.3 | 73.5 | 223 | ||||

| 121.5 | 75.5 | 226 | ||||

| 235 | Emsdale Bypass | |||||

| Parry Sound | Emsdale | 244 | Fern Glen Road west / Scotia Road east / Emsdale Road – Kearney | |||

| 248 | ||||||

| 252 | Doe Lake Road west / Three Mile Lake Road east | |||||

| Burk's Falls | 152.6 | 94.8 | 257 | Burk's Falls Bypass | ||

| 156.2 | 97.1 | 261 | Ontario Street / Pickerel & Jack Lake Road – Magnetawan | |||

| Sundridge | 171.6 | 106.6 | 276 | Sundridge / South River Bypass | ||

| South River | 178.7 | 111.0 | 282 | Machar Strong Boundary Road / Mountainview Road / Tower Road – Sundridge | ||

| 184.2 | 114.5 | 289 | ||||

| Laurier | 189.2 | 117.6 | 294 | Goreville Road / Summit Road | ||

| Trout Creek | 196.6 | 122.2 | 301 | Trout Creek Bypass | ||

| 201.4 | 125.1 | 306 | ||||

| Powassan | 211.9 | 131.7 | 316 | |||

| Callander | 224.9 | 139.7 | 329 | To | ||

| Nipissing | North Bay | 234.0 | 145.4 | 338 | Lakeshore Drive | Formerly Highway 11B north |

| 239.7 | 148.9 | 344 | South end of Highway 17 North Bay concurrency | |||

| 240.9 | 149.7 | Fisher Street | Formerly Highway 17B west | |||

| 241.5 | 150.1 | Cassells Street west | ||||

| 243.8 | 151.5 | Algonquin Avenue | North end of Highway 17 North Bay concurrency; formerly Highway 11B south | |||

| 244.3 | 151.8 | McKeown Avenue / Airport Road | ||||

| Marten River | 300.9 | 187.0 | ||||

| Timiskaming | Coleman | 380.4 | 236.4 | South end of Tri-Town Bypass | ||

| Temiskaming Shores | 389.9 | 242.3 | ||||

| 396.6 | 246.4 | South end of Highway 65 concurrency | ||||

| 399.3 | 248.1 | North end of Highway 65 concurrency; north end of Tri-Town Bypass; formerly Highway 11B south | ||||

| Hilliard | 411.1 | 255.4 | ||||

| Harley | 417.1 | 259.2 | ||||

| Earlton | 426.0 | 264.7 | ||||

| Heaslip | 434.7 | 270.1 | ||||

| Englehart | 440.9 | 274.0 | ||||

| Unorganized Timiskaming | 459.6 | 285.6 | ||||

| 478.6 | 297.4 | |||||

| Kenogami Lake | 479.6 | 298.0 | ||||

| Unorganized Timiskaming | 493.5 | 306.6 | ||||

| Cochrane | Unorganized Cochrane | 521.1 | 323.8 | |||

| Matheson | 535.6 | 332.8 | South end of Highway 101 concurrency | |||

| Unorganized Cochrane | 542.0 | 336.8 | North end of Highway 101 concurrency | |||

| 556.3 | 345.7 | |||||

| 556.6 | 345.9 | |||||

| Porquis Junction | 569.0 | 353.6 | ||||

| Nellie Lake | 575.9 | 357.8 | ||||

| Cochrane | 615.5 | 382.5 | directional signage changes | |||

| Unorganized Cochrane | 625.0 | 388.4 | ||||

| 633.5 | 393.6 | |||||

| Driftwood | 644.1 | 400.2 | ||||

| Smooth Rock Falls | 670.1 | 416.4 | ||||

| Moonbeam | 712.6 | 442.8 | ||||

| Kapuskasing | 727.3– 738.2 | 451.9– 458.7 | Kapuskasing Connecting Link | |||

| Hearst | 829.4 | 515.4 | ||||

| 830.0 | 515.7 | 6th Street | Beginning of Hearst Connecting Link | |||

| 830.6 | 516.1 | |||||

| 831.8 | 516.9 | 15th Street | End of Hearst Connecting Link | |||

| Unorganized Cochrane | 865.0 | 537.5 | ||||

| 893.8 | 555.4 | |||||

| Thunder Bay | Greenstone | 1,025.9 | 637.5 | |||

| 1,041.9 | 647.4 | Foresty Road – Longlac | No service between Longlac and Calstock off | |||

| 1,074.9 | 667.9 | |||||

| 1,130.5 | 702.5 | |||||

| 1,153.1 | 716.5 | |||||

| Nipigon | 1,232.3 | 765.7 | East end of Highway 17 Thunder Bay concurrency | |||

| 1,236.3 | 768.2 | |||||

| Unorganized Thunder Bay | 1,244.7 | 773.4 | ||||

| 1,260.2 | 783.1 | |||||

| 1,264.5 | 785.7 | |||||

| 1,300.8 | 808.3 | |||||

| 1,330.8 | 826.9 | |||||

| Thunder Bay | 1,334.6 | 829.3 | Hodder Avenue | Formerly Highway 11B / Highway 17B west | ||

| 1,341.0 | 833.3 | |||||

| 1,347.0 | 837.0 | Harbour Expressway east | ||||

| Unorganized Thunder Bay | 1,359.2 | 844.6 | ||||

| 1,368.6 | 850.4 | |||||

| Kakabeka Falls | 1,374.9 | 854.3 | ||||

| Unorganized Thunder Bay | 1,390.1 | 863.8 | ||||

| Shabaqua Corner | 1,411.1 | 876.8 | West end of Highway 17 Thunder Bay concurrency | |||

| Shebandowan | 1,431.9 | 889.7 | ||||

| Rainy River | Unorganized Rainy River | 1,517.9 | 943.2 | |||

| 1,524.9 | 947.5 | |||||

| 1,546.4 | 960.9 | To Highway 622 | ||||

| 1,662.1 | 1,032.8 | |||||

| Fort Frances | 1,688.3 | 1,049.1 | Beginning of Fort Frances Connecting Link | |||

| 1,690.9 | 1,050.7 | East end of Highway 71 concurrency | ||||

| 1,692.9 | 1,051.9 | |||||

| 1,696.9 | 1,054.4 | End of Fort Frances Connecting Link | ||||

| Unorganized Rainy River | 1,702.1 | 1,057.6 | Beginning of Highway 611 concurrency | |||

| 1,704.1 | 1,058.9 | End of Highway 611 concurrency | ||||

| Devlin | 1,713.9 | 1,065.0 | ||||

| Emo | 1,726.6 | 1,072.9 | ||||

| Unorganized Rainy River | 1,732.8 | 1,076.7 | West end of Highway 71 concurrency | |||

| Stratton | 1,751.7 | 1,088.5 | ||||

| Pinewood | 1,763.5 | 1,095.8 | ||||

| Unorganized Rainy River | 1,773.1 | 1,101.8 | ||||

| Rainy River | 1,782.0 | 1,107.3 | Beginning of Rainy River Connecting Link | |||

| 1,784.6 | 1,108.9 | End of Rainy River Connecting Link | ||||

| Canada–United States border (Baudette–Rainy River Border Crossing) | 1,784.9 | 1,109.1 | Baudette–Rainy River International Bridge across Rainy River | |||

| Continuation into Minnesota; to | ||||||

1.000 mi = 1.609 km; 1.000 km = 0.621 mi

| ||||||

Images

Highway 11 just north of North Bay. On the left the Brake Check area can be seen before trucks head into North Bay.

Highway 11 just north of North Bay. On the left the Brake Check area can be seen before trucks head into North Bay. As a 4-lane divided highway at North Waseosa Lake Road/Rockhaven Road interchange near Melissa.

As a 4-lane divided highway at North Waseosa Lake Road/Rockhaven Road interchange near Melissa.

Winter can pose serious driving hazards along Hwy 11 (near Temagami).

Winter can pose serious driving hazards along Hwy 11 (near Temagami). New 4-lane divided Hwy 11 (near Katrine).

New 4-lane divided Hwy 11 (near Katrine).

See also

- Webers, a fast-food restaurant located alongside the highway, near Orillia

References

Sources

- Ministry of Transportation of Ontario (2010). "Annual Average Daily Traffic (AADT) counts". Archived from the original on July 6, 2011. Retrieved March 3, 2016.

- Ontario Road Map (Map). Cartography by Geomatics Office. Ministry of Transportation. 2020–2021. §§ L25–P26, G1–K16.

- Marshall, Sean (April 13, 2011). "The end of Yonge Street". Spacing. Retrieved June 2, 2022.

- Cherry, Zena (September 2, 1977). "Big days for Ottawa Centre". The Globe and Mail. p. 11. ProQuest 1241439869.

- Perra, Meri (April 14, 2011). "The 'myth' of Yonge Street being the world's longest road lives on". Yahoo! News. Retrieved June 2, 2022.

- Google (September 1, 2022). "Highway 11 at the 45th parallel north" (Map). Google Maps. Google. Retrieved September 1, 2022.

- Northern Highways Program: 2010–2014 (PDF) (Report). Ministry of Transportation of Ontario. 2010. Archived from the original (PDF) on April 14, 2014.

- TBnewsWatch.com Staff (July 8, 2022). "Section of four-laned Highway 11-17 is set to open near Thunder Bay". Northern Ontario Business. Retrieved September 3, 2022.

- Shragge & Bagnato 1984, pp. 23–25.

- Stamp, Robert M. (1991). Early Days in Richmond Hill: A History of the Community to 1930 — Chapter 1: The Road through Richmond Hill. Richmond Hill Public Library Board. Retrieved November 10, 2017.

- Peppiatt, Liam. "Chapter 16: The Children's Friend". Robertson's Landmarks of Toronto Revisited. Archived from the original on September 22, 2018. Retrieved March 5, 2016.

- "Yonge Street's History". The Globe and Mail. August 4, 2001. Archived from the original on April 23, 2008. Retrieved December 30, 2019.

- Hunter, Andrew F. (1909). A History of Simcoe County. Vol. 1. Archived from the original on September 29, 2007.

- Shragge & Bagnato 1984, pp. 17–21.

- Dennis, Lloyd (June 13, 2003). "Breaking Into Muskoka". Cottage Times. Vol. 3, no. 2. Muskoka. p. 03. Retrieved May 23, 2022.

- Trussler, Hartley (August 2, 1974). "Reflections". The North Bay Nugget. Vol. 68, no. 41. p. 2. Retrieved May 23, 2022.

- Shragge & Bagnato 1984, pp. 21–25, 71–75.

- Shragge & Bagnato 1984, pp. 73–74.

- Shragge & Bagnato 1984, pp. 71–75.

- "Provincial Highways Assumed in 1920". Annual Report (Report) (1920 ed.). Department of Public Highways. April 26, 1921. pp. 42–45. Retrieved April 13, 2022 – via Internet Archive.

- "Provincial Highways Now Being Numbered". The Canadian Engineer. Monetary Times Print. 49 (8): 246. August 25, 1925.

Numbering of the various provincial highways in Ontario has been commenced by the Department of Public Highways. Resident engineers are now receiving metal numbers to be placed on poles along the provincial highways. These numbers will also be placed on poles throughout cities, towns and villages, and motorists should then have no trouble in finding their way in and out of urban municipalities. Road designations from "2" to "17" have already been allotted...

- "Highway Improvement in Ontario". Annual Report (Report) (1922 ed.). Department of Public Highways. May 28, 1923. p. 12. Retrieved May 24, 2022 – via Internet Archive.

- "Report on Provincial Highways — 1923". Annual Report (Report) (1923, 1924 and 1925 ed.). Department of Public Highways. April 26, 1926. p. 66. Retrieved May 24, 2022 – via Internet Archive.

- Ontario Road Map (Map). Ontario Department of Public Highways. 1925. Retrieved May 26, 2022 – via Archives of Ontario.

- "Provincial Highway Construction, 1926 / 1927". Annual Report (Report) (1926 and 1927 ed.). Department of Public Highways. March 1, 1929. pp. 22, 24. Retrieved May 26, 2022 – via Internet Archive.

- "Provincial Highway Construction, 1929". Annual Report (Report) (1928 and 1929 ed.). Department of Public Highways. March 3, 1931. p. 23. Retrieved May 26, 2022 – via Internet Archive.

- Ontario Road Map (Map). Cartography by D. Barclay. Ontario Department of Public Highways. 1930–31. § F4. Retrieved May 26, 2022 – via Archives of Ontario.

- "King's Highway Construction, 1930, 1931". Annual Report (Report) (1930 and 1931 ed.). Department of Highways. October 24, 1932. pp. 31–34. Retrieved May 27, 2022 – via Internet Archive.

- Ontario Road Map (Map). Cartography by D. Barclay. Ontario Department of Public Highways. 1931–32. §§ L5–M7. Retrieved May 27, 2022 – via Archives of Ontario.

- "Preparing for Visit of Boards". The Daily Nugget. Vol. 4, no. 126. June 19, 1912. p. 1. Retrieved May 28, 2022 – via Newspapers.com.

- "Would Sell Timber and Pay for Highway North". The Daily Nugget. Vol. 12, no. 132. June 26, 1920. p. 1. Retrieved May 28, 2022 – via Newspapers.com.

- "To Call Meeting Re: New Highway". The Daily Nugget. Vol. 12, no. 169. August 10, 1920. p. 1. Retrieved May 28, 2022 – via Newspapers.com.

- "More Publicity and New Roads". The Ottawa Citizen. Vol. 78, no. 95. October 2, 1920. p. 2. Retrieved May 28, 2022 – via Newspapers.com.

- "Committee is Given Earful at Timmins". The Daily Nugget. Vol. 14, no. 168. September 15, 1922. p. 7. Retrieved May 28, 2022 – via Newspapers.com.

- Ontario Road Map (Map). Ontario Department of Public Highways. 1926. Part of Northern Ontario inset. Retrieved May 28, 2022 – via Archives of Ontario.

- "Completion of Highway Urged". The Ottawa Evening Citizen. Vol. 80, no. 2013. February 8, 1923. p. 8. Retrieved May 28, 2022 – via Newspapers.com.

- Shragge & Bagnato 1984, p. 77.

- "Slashing for Northern Road is Completed". The Nugget. Vol. 17, no. 13. March 27, 1925. p. 12. Retrieved May 28, 2022 – via Newspapers.com.

- "Start on New Highway". The Daily Sun–Times. July 28, 1925. p. 5. Retrieved May 28, 2022 – via Newspapers.com.

- "Road Links North With Old Ontario". The Brantford Expositor. July 4, 1927. p. 4. Retrieved May 28, 2022 – via Newspapers.com.

- "Will Not Cut Road Budgets in the North". The Nugget. Vol. 19, no. 53. July 8, 1927. p. 10. Retrieved May 28, 2022 – via Newspapers.com.

- Annual Report (Report) (1930 ed.). Department of Northern Development. February 5, 1931. pp. 11–12. Retrieved May 30, 2022 – via Internet Archive.

- Annual Report (Report) (1932 ed.). Department of Northern Development. February 14, 1933. p. 16. Retrieved May 30, 2022 – via Internet Archive.

- Shragge & Bagnato 1984, p. 73.

- Ontario Road Map (Map). Cartography by D. Barclay. Ontario Department of Highways. 1938–39. § Mileage Tables. Retrieved May 26, 2022 – via Archives of Ontario.

- "Appendix No. 3 – Schedule of Assumptions and Reversions of Sections of the King's Highway System for the Fiscal Year". Annual Report (Report) (1938 ed.). Department of Highways. April 20, 1939. pp. 80–81. Retrieved October 2, 2022 – via Internet Archive.

- Lavoie, Edgar J. (October 2006). "History". Municipality of Greenstone. Retrieved March 4, 2016.

- "Large-Scale Highway Construction is Continued". The Windsor Star. December 31, 1938. p. 4. Retrieved June 1, 2022.

- "Open New Highway in Little Long Lac Area". North Bay Nugget. November 8, 1939. p. 9. Retrieved June 1, 2022.

- "Nipigon–Geraldton Highway". Annual Report (Report) (1940 ed.). Department of Highways. December 31, 1941. p. 43. Retrieved May 30, 2022 – via Internet Archive.

- "Appendix No. 3 – Schedule of Assumptions and Reversions of Sections of the King's Highway System for the Fiscal Year". Annual Report (Report) (1941 ed.). Department of Highways. December 31, 1942. p. 48. Retrieved May 30, 2022 – via Internet Archive.

- "Throne Speech Text". The Windsor Star. February 19, 1941. p. 14. Retrieved June 1, 2022.

- "Plan Prison Camps". Vancouver Sun. Vol. 54, no. 20. October 24, 1939. p. 8. Retrieved June 1, 2022.

- "50 More Convicts for Highway Work". Sault Daily Star. February 15, 1940. p. 6. Retrieved June 1, 2022.

- "Trans-Canada Highway Open Coast to Coast". Nanaimo Daily News. June 12, 1943. p. 1. Retrieved June 2, 2022.

- Ontario Road Map (Map). Cartography by J.W. Whitelaw. Ontario Department of Highways. 1946. § Mileage Tables. Retrieved June 3, 2022 – via Archives of Ontario.

- "Tenders Called For New Road Into Atikokan". The Globe and Mail. October 11, 1951. p. 23. ProQuest 1288366296. (subscription required)

- "New Bridge Is Needed To Help Fort Frances". Vol. 108, no. 81. The Evening Citizen. October 3, 1950. p. 4. Retrieved June 18, 2022 – via Newspapers.com. (subscription required)

- "New Highways Are Essential For Northern Ontario". Vol. 40, no. 159. The Sault Daily Star. September 22, 1950. p. 1. Retrieved June 18, 2022 – via Newspapers.com. (subscription required)

- "Brief Urges Road To Lakehead Cities". Vol. 38, no. 270. The Sault Daily Star. February 1, 1950. p. 1. Retrieved June 18, 2022 – via Newspapers.com. (subscription required)

- "Promise Atikokan Highway Link". Vol. 40, no. 125. The Sault Daily Star. August 13, 1951. p. 11. Retrieved June 18, 2022 – via Newspapers.com. (subscription required)

- "Approve Route of New Road". Vol. 40, no. 174. The Sault Daily Star. October 11, 1951. p. 1. Retrieved June 19, 2022 – via Newspapers.com. (subscription required)

- "Provincial Roundup: Northern Ontario". Vol. 45, no. 42. National Post. October 20, 1951. p. 13. Retrieved June 19, 2022 – via Newspapers.com. (subscription required)

- "Premier Frost Wields Ax Opening Atikokan Road". Vol. 43, no. 127. The Sault Daily Star. August 14, 1954. p. 8. Retrieved June 17, 2022 – via Newspapers.com. (subscription required)

- "Division No. 19 – Fort William". Annual Report (Report) (1954 ed.). Department of Highways. April 1, 1954. p. 103.

- Ontario Road Map (Map). Cartography by C.P. Robins. Ontario Department of Highways. 1959. Northern portion inset. § F4–H6.

- Ontario Road Map (Map). Cartography by C.P. Robins. Ontario Department of Highways. 1960. Northern portion inset. § F4–H6.

- Information Section (November 9, 1959). "[No title]" (Press release). Department of Highways.

- "The Noden Causeway". Fort Frances Times. Archived from the original on March 14, 2022. Retrieved December 1, 2018.

- "Provincial Highways Distance Table". Provincial Highways Distance Table: King's Secondary Highways and Tertiary Roads. Ministry of Transportation of Ontario: 27–32. 1989. ISSN 0825-5350.

- Engineering and Contract Record (Report). Vol. 76. Hugh C. MacLean publications. 1963. p. 121. Retrieved September 12, 2010.

The long-awaited Lakehead Expressway moved to the brink of reality when Ontario Highways Minister Charles S. MacNaughton announced a new cost-sharing formula for the twin cities portion. This fixes the expressway cost at $15,770,000.

- A.T.C. McNab (September 6–9, 1966). Proceedings of the Canadian Good Roads Association Convention. Canadian Good Roads Association. p. 73.

- A.T.C. McNab (September 27–30, 1965). Proceedings of the Canadian Good Roads Association Convention. Canadian Good Roads Association. p. 91.

- A.T.C. McNab (September 25–28, 1967). Proceedings of the Canadian Good Roads Association Convention. Canadian Good Roads Association. p. 61.

- A.T.C. McNab (September 29 – October 2, 1969). Proceedings of the Canadian Good Roads Association Convention. Canadian Good Roads Association. p. 66.

- "Appendix 16 - Schedule of Designations and Redesignations of Sections". Annual Report (Report). Department of Highways and Communications. March 31, 1971. pp. 151, 154.

- Ontario Road Map (Map). Cartography by Photogrammetry Office. Department of Transportation and Communications. 1970. Thunder Bay inset.

- Ontario Road Map (Map). Cartography by Photogrammetry Office. Department of Transportation and Communications. 1971. Thunder Bay inset.

- "Division No. 11—Huntsville". Annual Report (Report) (1947 ed.). Department of Highways. December 17, 1948. p. 63.

- "Division No. 11—Huntsville". Annual Report (Report) (1949 ed.). Department of Highways. March 21, 1950. p. 59.

- "To Speed Up Four-Laner". The Daily Nugget. Vol. 61, no. 282. May 16, 1968. p. 1. Retrieved June 24, 2022 – via Newspapers.com.

- "Report of the Chief Engineer, W. A. Clarke". Annual Report (Report) (1954 ed.). Department of Highways. April 1, 1955. p. 14.

- "Report of the Chief Engineer, W. A. Clarke". Annual Report (Report) (1955 ed.). Department of Highways. April 1, 1956. p. 12.

- "We're Gradually Getting Good Road". The Daily Nugget. Vol. 46, no. 301. July 27, 1953. p. 4. Retrieved June 24, 2022 – via Newspapers.com.

- "Division No. 13—North Bay". Annual Report (Report) (1953 ed.). Department of Highways. April 1, 1954. p. 85.

- "Report of Chief Engineer W. A. Clarke". Annual Report (Report) (1956 ed.). Department of Highways. April 1, 1957. p. 18.

- "Report of the Chief Engineer, W. A. Clarke". Annual Report (Report) (1957 ed.). Department of Highways. February 23, 1959. p. 19.

- "Chronology—Department of Highways". Annual Report (Report) (1959 ed.). Department of Highways. December 20, 1960. p. 295.

- "District No. 13—North Bay, Appendix No. 3A: Schedule of Designations and Redesignations of Sections of the King's Highway and Secondary Highway Systems". Annual Report (Report) (1959 ed.). Department of Highways. December 20, 1960. pp. 132, 264.

- "District No. 14—New Liskeard". Annual Report (Report) (1964 ed.). Department of Highways. December 20, 1960. p. 153.

- Young, Gord (August 31, 2005). "Highway projects unveiled". North Bay Nugget. p. 1. Retrieved August 27, 2022 – via Newspapers.com.

- Hamilton-McCharles, Jennifer (May 21, 2010). "4-laning moving ahead". North Bay Nugget. pp. 1, 3. Retrieved August 28, 2022 – via Newspapers.com.

- "Huge highway outlay includes 4-lane job north of Bracebridge". North Bay Nugget. June 1, 1974. p. 13. Retrieved August 28, 2022 – via Newspapers.com.

- "Deputy Ministers Report". Annual Report (Report) (1965 ed.). Department of Highways. December 3, 1965. p. 13.

- "Summary of the Report". Annual Report (Report) (1966 ed.). Department of Highways. December 3, 1967. p. xvii.

- "Highway bypass of Gravenhurst". The Windsor Star. Vol. 96, no. 30. April 4, 1966. p. 21. Retrieved August 26, 2022 – via Newspapers.com.

- "Chronology". Annual Report (Report) (1966 ed.). Department of Highways. December 3, 1967. p. 315.

- "Plan New Bypass Near Gravenhurst". The Owen Sound Sun-Times. Vol. 113, no. 105. April 5, 1966. p. 4. Retrieved June 24, 2022 – via Newspapers.com.

- "Northern Region: Huntsville, Sudbury, North Bay and New Liskeard Districts". Annual Report (Report) (1970 ed.). Department of Highways. March 31, 1971. p. 32.

On Highway 11 the Gravenhurst Bypass proceeded with the completion of the Gull Lake structures and the paving and opening to traffic of the four lanes, a distance of 4.25 miles.

- Ontario Road Map (Map). Cartography by Photogrammetry Office. Department of Transportation and Communications. 1971. § G–H23. Retrieved August 28, 2022 – via Archives of Ontario.

- "Northern Region Functional Planning". Annual Report (Report) (1970 ed.). Department of Highways. March 31, 1971. p. 10.

Major projects carried out during the year included work on 4-lane Highway 11, Gravenhurst northerly

- Ontario Road Map (Map). Cartography by Cartography Section. Ministry of Transportation and Communications. 1974. § F–G23. Retrieved August 28, 2022 – via Archives of Ontario.

- "We receive generous share of Ont. highway spending". North Bay Nugget. Vol. 72, no. 48. April 6, 1979. p. 4. Retrieved August 28, 2022 – via Newspapers.com.

- Dexter, Brian (July 11, 1996). "Province transfers highways to York But region won't be getting compensation, minister says". Toronto Star. p. NY1. ProQuest 437503977 (subscription required).

The province shelled out $9 million for upgrading when it handed over 36 kilometres of Yonge St. between Steeles Ave. and Bradford on April 1.

- Highway Transfers List (Report). Ministry of Transportation of Ontario. April 1, 1997. p. 7.

- Google (September 1, 2022). "Former route of Highway 11 south of Crown Hill prior to 1996" (Map). Google Maps. Google. Retrieved September 1, 2022.

- Ontario Road Map (Map). Cartography by Surveys and Mapping Section, Surveys and Design Office. Ministry of Transportation. 1998. §§ A9–G10. Retrieved September 1, 2022 – via Archives of Ontario.

- "Sault to receive $9.5 million to pave way for 2 road construction projects". The Sault Star. July 29, 1989. p. B1 – via Newspapers.com (subscription required).

- Hartill, Mary Beth (August 16, 2012). "Four-laning finally done". Huntsville Forester. Metroland Media Group. Retrieved September 1, 2022.

- Young, Gord (August 10, 2012). "Highway 11 four-laning complete". North Bay Nugget. Canoe Sun Media. Archived from the original on July 14, 2014. Retrieved December 30, 2019.

- "Eves government opens new four-laning on Highway 11" (Press release). Canada NewsWire. October 2, 2002. ProQuest 453394094 (subscription required).

- "Highway 11 bridge collapses: 'I heard what sounded like shotgun blasts'". Sudbury Star. January 16, 2003. p. A5. ProQuest 348823537 (subscription required).

- "Temporary bridge opens in Latchford". Sudbury Star. January 28, 2003. p. A2. ProQuest 348879139 (subscription required).

- "Up and running". Sudbury Star. March 5, 2003. p. A2. ProQuest 348816658 (subscription required).

- Ben-Daya, Mohamed; Kumar, Uday; Prabhakar Murthy, D. N. (2016). Introduction to Maintenance Engineering: Modelling, Optimization and Management. John Wiley & Sons. p. 68. ISBN 978-1-118-48719-8.

- Åkesson, Björn (2008). Understanding Bridge Collapses. Taylor & Francis. pp. 243–245. ISBN 978-0-415-43623-6.

- Cramer, Brandi (Oct 30, 2004). "10-km stretch of highway officially opens". North Bay Nugget. p. A3. ProQuest 352263673 (subscription required).

- "Part of new highway opens". North Bay Nugget. October 25, 2005. p. A2. ProQuest 352187908 (subscription required).

- Clarke, Dawn (June 27, 2009). "Hwy 11. 4-laning on schedule". North Bay Nugget. Outlook 2009, A6. Retrieved September 2, 2022 – via Newspapers.com (subscription required).

- "Shorter delay for commuters". North Bay Nugget. September 20, 2011. pp. 1, 3. Retrieved September 2, 2022 – via Newspapers.com (subscription required).

- "Accesllerated highway improvement program for Northwestern Ontario" (PDF). The Nipigon-Red Rock Gazette. Vol. 25, no. 51. December 19, 1989. pp. 1, 15. Retrieved September 4, 2022.

- H. Makela; G. Norman; B. MacMaster (January 1997). Environmental Study Report: Four-Laning of Highway 11/17 From 8km West of Ouimet Easterly 36km to the Red Rock Township West Boundary - W.P. 373-90-00 (PDF) (Report). p. iii. Retrieved September 4, 2022.

- "Project Background". Highway 11/17 Four-Laning (Pearl) - Municipality of Shuniah. Dillon Consulting. Retrieved September 4, 2022.

- Staff (August 17, 2012). "Open for business: MTO opens new section of divided highway". TBNewsWatch.com. Retrieved September 3, 2022.

- Staff (August 9, 2011). "New highway lanes opened near Terry Fox Lookout". TBNewsWatch.com. Retrieved September 3, 2022.

- "Current Status of Hwy 11/17 Four Laning - Thunder Bay to Nipigon". Highway 11/17 Four-Laning from Pearl Lake, Easterly to 2.8 km West of CPR Overhead at Ouimet Class Environmental Assessment (Class EA) Study: Online Public Information Centre #1 (PDF) (Report). WSP Global. July 2021. p. 8. Retrieved September 3, 2022.

- Staff (November 16, 2012). "New highway four-laning contract awarded". TBNewsWatch.com. Retrieved September 4, 2022.

- "Hwy 11-17 speeds to stay at 90 km/hr". CBC News. July 31, 2013. Retrieved September 4, 2022.

- Murray, James (September 29, 2014). "More Twinned Highway Near Nipigon". Net News Ledger. Retrieved September 3, 2022.

- "Nipigon River Bridge". McElhanney. Retrieved September 5, 2022.

- "Traffic flows across new Nipigon bridge". The Chronicle-Journal. Thunder Bay. November 29, 2015. Retrieved November 10, 2017.

- "Nipigon River Bridge — Construction Updates". Hatch. Retrieved November 10, 2017.

- Husser, Amy (January 10, 2016). "Ontario's Nipigon River bridge fails, severing Trans-Canada Highway". CBC News. Retrieved September 5, 2022.

- "Nipigon River Bridge reopens to 2 lanes on Thursday". CBC News. February 24, 2016. Retrieved September 5, 2022.

- "Nipigon Bridge finally opens to four lanes". Northern Ontario Business. Vol. 39, no. 3. January 2019. p. 3. ProQuest 2172620620 (subscription required).

- Paradis, Scott (June 10, 2015). "Contracts worth $120M for highway four-laning awarded". TBNewsWatch.com. Retrieved September 4, 2022.

- "Ontario Liberals update progress on Hwy 11/17 four-laning project". CBC News. August 11, 2017. Retrieved September 4, 2022.

- Vis, Matt (August 11, 2017). "Highway twinning nears milestone". TBNewsWatch.com. Retrieved September 4, 2022.

- "Teranorth Completed Projects". Teranorth Construction. February 10, 2022. Retrieved September 4, 2022.

2014-6018 Hwy 11/17 - Four-Laning Pass Lake Design Build Ministry of Transportation $32,729,000.00 9/1/2017

- Ranger, Michael (April 22, 2022). "110 km/h speed limits now permanent on six Ontario highway sections". CityNews. Retrieved September 5, 2022.

- "R.R.O. 1990, Reg. 619: SPEED LIMITS". e-Laws. Government of Ontario. Schedule 13. Retrieved September 5, 2022.

That part of the King's Highway known as No. 11 lying between a point situate 140 metres measured northerly from its intersection with the centre line of the King's Highway known as No. 7188 (Katrine Road) ... and a point situate 2,600 metres measured southerly from its intersection with the centre line of the roadway known as Goreville Road

- Staff (December 8, 2020). "A new Highway 11-17 twinning project begins". TBNewsWatch.com. Retrieved September 3, 2022.

- Hardy, Justin (April 9, 2022). "Ontario announces $107 million contract for highway twinning project". TBNewsWatch.com. Retrieved September 3, 2022.

- "Teranorth Construction awarded $107M contract for Highway 11/17 twinning". Link2Build Ontario. April 10, 2022. Retrieved September 13, 2022.

- "Highway 11: Washago to Gravenhurst". highway11study.ca. Province of Ontario. October 3, 2012. Archived from the original on January 14, 2014. Retrieved 1 December 2018.

Bibliography

- Shragge, John; Bagnato, Sharon (1984). From Footpaths to Freeways. Ontario Ministry of Transportation and Communications, Historical Committee. ISBN 0-7743-9388-2.

External links

- Ontario Plaques – Ferguson Highway

- Ontario Highway 11 Homepage – A Virtual Community-by-Community Trip Along the World's Longest Street

- Highway 11 @ AsphaltPlanet.ca

- Four-laning studies Thunder Bay–Nipigon

- Highway 11/17 Four-Laning (Pearl), Municipality of Shuniah

- Highway 11/17 Four-Laning: From Pearl Lake, easterly to 2.8 km west of CPR Overhead at Ouimet, 7.6km

- Highway 11/17 Four-Laning from Ouimet to Dorion

- Highway 11/17 Four-Laning: From east of Junction Highway 582 westerly to Dorion, 11 km

- Highway 11/17 Expansion from west of Highway 582 to Coughlin Road

- Highway 11/17 Expansion from Coughlin Road to Red Rock Road #9