Transantarctic Mountains

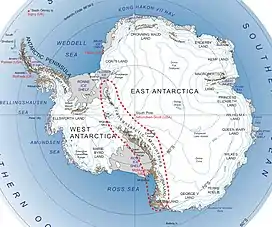

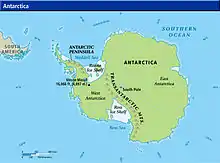

The Transantarctic Mountains (abbreviated TAM) comprise a mountain range of uplifted rock (primarily sedimentary) in Antarctica which extends, with some interruptions, across the continent from Cape Adare in northern Victoria Land to Coats Land. These mountains divide East Antarctica and West Antarctica. They include a number of separately named mountain groups, which are often again subdivided into smaller ranges.

| Transantarctic Mountains | |

|---|---|

The Transantarctic Mountains in northern Victoria Land near Cape Roberts | |

| Highest point | |

| Peak | Mount Kirkpatrick |

| Elevation | 4,528 m (14,856 ft) |

| Coordinates | 84°20′S 166°25′E |

| Dimensions | |

| Length | 3,500 km (2,200 mi) |

| Geography | |

| |

| Continent | Antarctica |

| Range coordinates | 85°S 175°W |

| Geology | |

| Age of rock | Cenozoic |

The range was first sighted by James Clark Ross in 1841 at what was later named the Ross Ice Shelf in his honour. It was first crossed during the British National Antarctic Expedition of 1901-1904.

Geography

The mountain range stretches between the Ross Sea and the Weddell Sea, the entire width of Antarctica, hence the name. With a total length of about 3,500 km (2,000 mi), the Transantarctic Mountains are one of the longest mountain ranges on Earth. The Antarctandes are even longer, having in common with the Transantarctic Mountains the ranges from Cape Adare to the Queen Maud Mountains, but extending thence through the Whitmore Mountains and Ellsworth Mountains up the Antarctic Peninsula. The 100–300 km (60–200 mi) wide range forms the boundary between East Antarctica and West Antarctica. The East Antarctic Ice Sheet bounds the TAM along their entire length on the Eastern Hemisphere side, while the Western Hemisphere side of the range is bounded by the Ross Sea in Victoria Land from Cape Adare to McMurdo Sound, the Ross Ice Shelf from McMurdo Sound to near the Scott Glacier, and the West Antarctic Ice Sheet beyond.

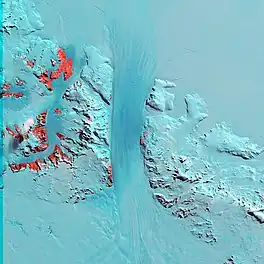

The summits and dry valleys of the TAM are some of the few places in Antarctica not covered by ice, the highest of which rise more than 4,500 metres (14,800 ft) above sea level. The McMurdo Dry Valleys lie near McMurdo Sound and represent a special Antarctic phenomenon: landscapes that are snow and ice-free due to the extremely limited precipitation and ablation of ice in the valleys. The highest mountain of the TAM is the 4,528 m (14,856 ft) high Mount Kirkpatrick in the Queen Alexandra Range.

Biology

Penguins, seals, and sea birds live along the Ross Sea coastline in Victoria Land, while life in the interior of the Transantarctic Range is limited to bacteria, lichens, algae, and fungi. Forests once covered Antarctica, including plentiful Wollemi pines and southern beeches.[1] However, with the gradual cooling associated with the break-up of Gondwana, these forests gradually disappeared.[1] It is believed that the last trees on the Antarctic continent were on Transantarctic Mountains.[1]

History

The Transantarctic Mountains were first seen by Captain James Clark Ross in 1841 from the Ross Sea. The range is a natural barrier that must be crossed to reach the South Pole from the Ross Ice Shelf.

The first crossing of the Transantarctic Mountains took place during the 1902–1904 British National Antarctic Expedition at the Ross Ice Shelf. A reconnaissance party under the command of Albert Armitage reached 2,700 m (8,900 ft) altitude in 1902. The following year, a party under expedition leader Robert Falcon Scott crossed into East Antarctica at a location now known as Ferrar Glacier, named after the geologist of the expedition. They explored part of Victoria Land on the Antarctic Plateau before returning via the same glacier. In 1908, Ernest Shackleton's party crossed the mountains through the Beardmore Glacier. Scott returned to that same glacier in 1911, while Roald Amundsen crossed the range via the Axel Heiberg Glacier.

Much of the range remained unexplored until the late 1940s and 1950s, when missions such as Operation Highjump and the International Geophysical Year (IGY) made extensive use of aerial photography and concentrated on a thorough investigation of the entire continent. The name "Transantarctic Mountains" was first applied to this range in a 1960 paper[2] by geologist Warren B. Hamilton, following his IGY fieldwork. It was subsequently recommended by the Advisory Committee on Antarctic Names, a US authority on geographic names, in 1962. This purely descriptive label (in contrast to many other geographic names on Antarctica) is internationally accepted at present.

The Leverett Glacier in the Queen Maud Mountains is the planned route through the TAM for the overland supply road between McMurdo Station and Amundsen–Scott South Pole Station.

Geology

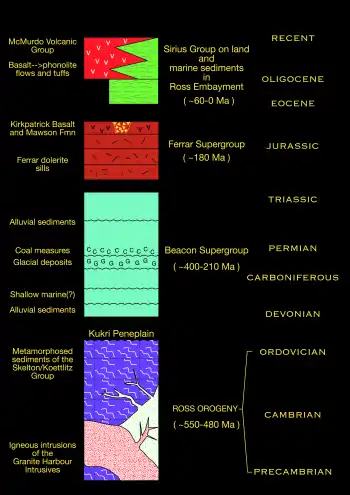

The Transantarctic Mountains are considerably older than other mountain ranges of the continent, which are mainly volcanic in origin. The range was uplifted during the opening of the West Antarctic Rift System to the east, beginning about 65 million years ago in the early Cenozoic, and soon after became occupied by glaciers.[3]

The mountains consist of sedimentary layers lying upon a basement of granites and gneisses. The sedimentary layers include the Beacon Supergroup sandstones, siltstones, and coal deposited beginning in the Silurian period and continuing into the Jurassic. In many places, the Beacon Supergroup has been intruded by dikes and sills of Jurassic age Ferrar Dolerite. Many of the fossils found in Antarctica are from locations within these sedimentary formations.

Ice from the East Antarctic Ice Sheet flows through the Transantarctic Mountains via a series of outlet glaciers into the Ross Sea, Ross Ice Shelf, and West Antarctic Ice Sheet. These glaciers generally flow perpendicular to the orientation of the range and define subranges and peak groups. It has been thought that many of these outlet glaciers follow the traces of large-scale geologic faults. However, the ice flow theories will be re-evaluated in light of new data from recent ice-penetrating radar surveys which revealed the presence of three previously unknown deep subglacial valleys affecting the "mountainous subglacial topography beneath the ice divide".[4] These geographic features are likely to have a significant impact on models and calculations related to ice flow through the Transantarctic Mountain region.[4]

See also

In geographic order, from the Ross Sea towards the Weddell Sea:

Victoria Land

Central TAM

Queen Maud Mountains

Further reading

- Gunter Faure, Teresa M. Mensing, The Transantarctic Mountains: Rocks, Ice, Meteorites and Water, Springer

- Damien Gildea, Transantarctic Mountains - Mountaineering in Antarctica: Travel Guide

- Sokol, E. R., C. W. Herbold, C. K. Lee, S. C. Cary, and J. E. Barrett, Local and regional influences over soil microbial metacommunities in the Transantarctic Mountains, Ecosphere 4(11):136. https://dx.doi.org/10.1890/ ES13-00136.1 2013

- I.B. Campbell, G.G.C. Claridge, Antarctica: Soils, Weathering Processes and Environment, PP 30 – 32

- A.R. Lewis, D.R. Marchant, A.C. Ashworth, S.R. Hemming, M.L. Machlus, Major middle Miocene global climate change: Evidence from East Antarctica and the Transantarctic Mountains

References

- Woodford, J. 2000. The Wollemi Pine. Melbourne: Text Publishing. pp. 85-104

- U.S. Geological Survey Professional Paper. U.S. Government Printing Office. 1960.

- Barr, Iestyn D.; Spagnolo, Matteo; Rea, Brice R.; Bingham, Robert G.; Oien, Rachel P.; Adamson, Kathryn; Ely, Jeremy C.; Mullan, Donal J.; Pellitero, Ramón; Tomkins, Matt D. (21 September 2022). "60 million years of glaciation in the Transantarctic Mountains". Nature Communications. 13 (1): 5526. doi:10.1038/s41467-022-33310-z. ISSN 2041-1723. PMC 9492669. PMID 36130952.

- Winter, K.; Ross, N.; et al. (2018). "Topographic Steering of Enhanced Ice Flow at the Bottleneck Between East and West Antarctica". Geophysical Research Letters. 45 (10): 4899–907. Bibcode:2018GeoRL..45.4899W. doi:10.1029/2018GL077504.

.svg.png.webp)