Transubstantiation

Transubstantiation (Latin: transubstantiatio; Greek: μετουσίωσις metousiosis) is, according to the teaching of the Catholic Church, "the change of the whole substance of bread into the substance of the Body of Christ and of the whole substance of wine into the substance of the Blood of Christ".[1][2] This change is brought about in the eucharistic prayer through the efficacy of the word of Christ and by the action of the Holy Spirit.[3] However, "the outward characteristics of bread and wine, that is the 'eucharistic species', remain unaltered".[1] In this teaching, the notions of "substance" and "transubstantiation" are not linked with any particular theory of metaphysics.[4][5]

| Part of a series on the |

| Eucharist |

|---|

|

The Roman Catholic Church teaches that, in the Eucharistic offering, bread and wine are changed into the body and blood of Christ.[6] The affirmation of this doctrine on the real presence of Christ in the Eucharist was expressed, using the word "transubstantiate", by the Fourth Council of the Lateran in 1215.[7][8] It was later challenged by various 14th-century reformers, John Wycliffe in particular.[9]

The manner in which the change occurs, the Roman Catholic Church teaches, is a mystery: "The signs of bread and wine become, in a way surpassing understanding, the Body and Blood of Christ."[10] In Lutheranism, the terminology used regarding the real presence is the doctrine of the sacramental union, while in Anglicanism, the precise terminology to be used to refer to the nature of the Eucharist has a contentious interpretation: "bread and cup" or "Body and Blood"; "set before" or "offer"; "objective change" or "new significance".[11][12]

In the Greek Orthodox Church, the doctrine has been discussed under the term of metousiosis, coined as a direct loan-translation of transubstantiatio in the 17th century. In Eastern Orthodoxy in general, the Sacred Mystery (Sacrament) of the Eucharist is more commonly discussed using alternative terms such as "trans-elementation" (μεταστοιχείωσις, metastoicheiosis), "re-ordination" (μεταρρύθμισις, metarrhythmisis), or simply "change" (μεταβολή, metabole).

History

Summary

From the earliest centuries, the Church spoke of the elements used in celebrating the Eucharist as being changed into the body and blood of Christ. Terms used to speak of the alteration included "trans-elementation."[13] The bread and wine were said to be "made",[14] "changed into",[15] the body and blood of Christ. Similarly, Augustine said: "Not all bread, but only that which receives the blessing of Christ becomes the body of Christ."[16]

The term "transubstantiation" was used at least by the 11th century to speak of the change and was in widespread use by the 12th century. The Fourth Council of the Lateran used it in 1215. When later theologians adopted Aristotelian metaphysics in Western Europe, they explained the change that was already part of Catholic teaching in terms of Aristotelian substance and accidents. The sixteenth-century Reformation gave this as a reason for rejecting the Catholic teaching. The Council of Trent did not impose the Aristotelian theory of substance and accidents or the term "transubstantiation" in its Aristotelian meaning, but stated that the term is a fitting and proper term for the change that takes place by consecration of the bread and wine. The term, which for that Council had no essential dependence on scholastic ideas, is used in the Catholic Church to affirm the fact of Christ's presence and the mysterious and radical change which takes place, but not to explain how the change takes place,[17] since this occurs "in a way surpassing understanding".[10] The term is mentioned in both the 1992 and 1997 editions of the Catechism of the Catholic Church and is given prominence in the later (2005) Compendium of the Catechism of the Catholic Church.

Patristic period

Early Christian writers referred to the Eucharistic elements as Jesus's body and the blood.[19][20] The short document known as the Teachings of the Apostles or Didache, which may be the earliest Christian document outside of the New Testament to speak of the Eucharist, says, "Let no one eat or drink of your Eucharist, unless they have been baptized into the name of the Lord; for concerning this also the Lord has said, 'Give not that which is holy to the dogs'."[21]

Ignatius of Antioch, writing in about AD 106 to the Roman Christians, says: "I desire the bread of God, the heavenly bread, the bread of life, which is the flesh of Jesus Christ, the Son of God, who became afterwards of the seed of David and Abraham; and I desire the drink of God, namely His blood, which is incorruptible love and eternal life."[22]

Writing to the Christians of Smyrna in the same year, he warned them to "stand aloof from such heretics", because, among other reasons, "they abstain from the Eucharist and from prayer, because they confess not the Eucharist to be the flesh of our Saviour Jesus Christ, which suffered for our sins, and which the Father, of His goodness, raised up again."[19]

In about 150, Justin Martyr, referring to the Eucharist, wrote: "Not as common bread and common drink do we receive these; but in like manner as Jesus Christ our Savior, having been made flesh by the Word of God, had both flesh and blood for our salvation, so likewise have we been taught that the food which is blessed by the prayer of His word, and from which our blood and flesh by transmutation are nourished, is the flesh and blood of that Jesus who was made flesh."[23]

In about AD 200, Tertullian wrote: "Having taken the bread and given it to His disciples, He made it His own body, by saying, This is my body, that is, the figure of my body. A figure, however, there could not have been, unless there were first a veritable body. An empty thing, or phantom, is incapable of a figure. If, however, (as Marcion might say) He pretended the bread was His body, because He lacked the truth of bodily substance, it follows that He must have given bread for us."[24]

The Apostolic Constitutions (compiled c. 380) says: "Let the bishop give the oblation, saying, The body of Christ; and let him that receiveth say, Amen. And let the deacon take the cup; and when he gives it, say, The blood of Christ, the cup of life; and let him that drinketh say, Amen."[25]

Ambrose of Milan (died 397) wrote:

Perhaps you will say, "I see something else, how is it that you assert that I receive the Body of Christ?" ...Let us prove that this is not what nature made, but what the blessing consecrated, and the power of blessing is greater than that of nature, because by blessing nature itself is changed. ...For that sacrament which you receive is made what it is by the word of Christ. But if the word of Elijah had such power as to bring down fire from heaven, shall not the word of Christ have power to change the nature of the elements? ...Why do you seek the order of nature in the Body of Christ, seeing that the Lord Jesus Himself was born of a Virgin, not according to nature? It is the true Flesh of Christ which was crucified and buried, this is then truly the Sacrament of His Body. The Lord Jesus Himself proclaims: "This Is My Body." Before the blessing of the heavenly words another nature is spoken of, after the consecration the Body is signified. He Himself speaks of His Blood. Before the consecration it has another name, after it is called Blood. And you say, Amen, that is, It is true. Let the heart within confess what the mouth utters, let the soul feel what the voice speaks.[20]

Other fourth-century Christian writers say that in the Eucharist there occurs a "change",[26] "transelementation",[27] "transformation",[28] "transposing",[29] "alteration"[30] of the bread into the body of Christ.

Augustine declares that the bread consecrated in the Eucharist actually "becomes" (in Latin, fit) the Body of Christ: "The faithful know what I'm talking about; they know Christ in the breaking of bread. It isn't every loaf of bread, you see, but the one receiving Christ's blessing, that becomes the body of Christ."[31]

Clement of Alexandria, who uses the word "symbol" concerning the Eucharist, is quoted as an exception,[32] although this interpretation is disputed on the basis of Alexandrian overlaps of symbology and literalism.[33]

Middle Ages

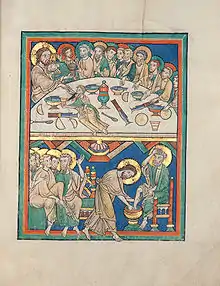

Paschasius Radbertus (785–865) was a Carolingian theologian, and the abbot of Corbie, whose most well-known and influential work is an exposition on the nature of the Eucharist written around 831, entitled De Corpore et Sanguine Domini. In it, Paschasius agrees with Ambrose in affirming that the Eucharist contains the true, historical body of Jesus Christ. According to Paschasius, God is truth itself, and therefore, his words and actions must be true. Christ's proclamation at the Last Supper that the bread and wine were his body and blood must be taken literally, since God is truth.[34] He thus believes that the change of the substances of the bread and wine into the body and blood of Christ offered in the Eucharist really occurs. Only if the Eucharist is the actual body and blood of Christ can a Christian know it is salvific.[35]

In the 11th century, Berengar of Tours stirred up opposition when he denied that any material change in the elements was needed to explain the fact of the Real Presence. His position was never diametrically opposed to that of his critics, and he was probably never excommunicated, but the controversies that he aroused (see Stercoranism) forced people to clarify the doctrine of the Eucharist.[36]

The earliest known use of the term transubstantiation to describe the change from bread and wine to body and blood of Christ in the Eucharist was by Hildebert de Lavardin, Archbishop of Tours, in the 11th century.[37] By the end of the 12th century the term was in widespread use.[38]

The Fourth Council of the Lateran in 1215 spoke of the bread and wine as "transubstantiated" into the body and blood of Christ: "His body and blood are truly contained in the sacrament of the altar under the forms of bread and wine, the bread and wine having been transubstantiated, by God's power, into his body and blood".[39][40] Catholic scholars and clergy have noted numerous reports of Eucharistic miracles contemporary with the council, and at least one such report was discussed at the council.[41][42] It was not until later in the 13th century that Aristotelian metaphysics was accepted and a philosophical elaboration in line with that metaphysics was developed, which found classic formulation in the teaching of Thomas Aquinas[38] and in the theories of later Catholic theologians in the medieval period (Robert Grosseteste,[43] Giles of Rome, Duns Scotus and William of Ockham).[44][45]

Reformation

During the Protestant Reformation, the doctrine of transubstantiation was heavily criticised as an Aristotelian "pseudophilosophy"[46] imported into Christian teaching and jettisoned in favor of Martin Luther's doctrine of sacramental union, or in favor, per Huldrych Zwingli, of the Eucharist as memorial.[47]

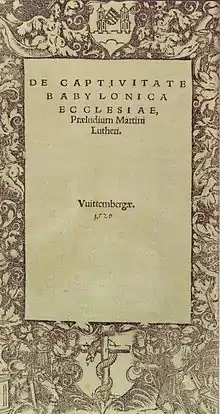

In the Reformation, the doctrine of transubstantiation became a matter of much controversy. Martin Luther held that "It is not the doctrine of transubstantiation which is to be believed, but simply that Christ really is present at the Eucharist".[48] In his On the Babylonian Captivity of the Church (published on 6 October 1520) Luther wrote:

Therefore, it is an absurd and unheard-of juggling with words, to understand "bread" to mean "the form, or accidents of bread", and "wine" to mean "the form, or accidents of wine". Why do they not also understand all other things to mean their forms, or accidents? Even if this might be done with all other things, it would yet not be right thus to emasculate the words of God and arbitrarily to empty them of their meaning. Moreover, the Church had the true faith for more than twelve hundred years, during which time the holy Fathers never once mentioned this transubstantiation – certainly, a monstrous word for a monstrous idea – until the pseudo-philosophy of Aristotle became rampant in the Church these last three hundred years. During these centuries many other things have been wrongly defined, for example, that the Divine essence neither is begotten nor begets, that the soul is the substantial form of the human body, and the like assertions, which are made without reason or sense, as the Cardinal of Cambray himself admits.[49]

In his 1528 Confession Concerning Christ's Supper, he wrote:

Why then should we not much more say in the Supper, "This is my body", even though bread and body are two distinct substances, and the word "this" indicates the bread? Here, too, out of two kinds of objects a union has taken place, which I shall call a "sacramental union", because Christ's body and the bread are given to us as a sacrament. This is not a natural or personal union, as is the case with God and Christ. It is also perhaps a different union from that which the dove has with the Holy Spirit, and the flame with the angel, but it is also assuredly a sacramental union.[50]

What Luther thus called a "sacramental union" is often erroneously called "consubstantiation" by non-Lutherans. In On the Babylonian Captivity, Luther upheld belief in the Real Presence of Jesus and, in his 1523 treatise The Adoration of the Sacrament, defended adoration of the body and blood of Christ in the Eucharist.

In the Six Articles of 1539, the death penalty is specifically prescribed for any who denied transubstantiation.

This was changed under Elizabeth I. In the 39 articles of 1563, the Church of England declared: "Transubstantiation (or the change of the substance of Bread and Wine) in the Supper of the Lord, cannot be proved by holy Writ; but is repugnant to the plain words of Scripture, overthroweth the nature of a Sacrament, and hath given occasion to many superstitions".[51] Laws were enacted against participation in Catholic worship, which remained illegal until 1791.[52][53]

For a century and half – 1672 to 1828 – transubstantiation had an important role, in a negative way, in British political and social life. Under the Test Act, the holding of any public office was made conditional upon explicitly denying Transubstantiation. Any aspirant to public office had to repeat the formula set out by the law: "I, N, do declare that I do believe that there is not any transubstantiation in the sacrament of the Lord's Supper, or in the elements of the bread and wine, at or after the consecration thereof by any person whatsoever."

Council of Trent

In 1551, the Council of Trent declared that the doctrine of transubstantiation is a dogma of faith[54] and stated that "by the consecration of the bread and wine there takes place a change of the whole substance of the bread into the substance of the body of Christ our Lord and of the whole substance of the wine into the substance of his blood. This change the holy Catholic Church has fittingly and properly called transubstantiation."[55] In its 13th session ending 11 October 1551, the Council defined transubstantiation as "that wonderful and singular conversion of the whole substance of the bread into the Body, and of the whole substance of the wine into the Blood – the species only of the bread and wine remaining – which conversion indeed the Catholic Church most aptly calls Transubstantiation".[55] This council officially approved use of the term "transubstantiation" to express the Catholic Church's teaching on the subject of the conversion of the bread and wine into the body and blood of Christ in the Eucharist, with the aim of safeguarding Christ's presence as a literal truth, while emphasizing the fact that there is no change in the empirical appearances of the bread and wine.[56] It did not however impose the Aristotelian theory of substance and accidents: it spoke only of the species (the appearances), not the philosophical term "accidents", and the word "substance" was in ecclesiastical use for many centuries before Aristotelian philosophy was adopted in the West,[57] as shown for instance by its use in the Nicene Creed which speaks of Christ having the same "οὐσία" (Greek) or "substantia" (Latin) as the Father.

Since the Second Vatican Council

The Catechism of the Catholic Church states the Church's teaching on transubstantiation twice.

It repeats what it calls the Council of Trent's summary of the Catholic faith on "the conversion of the bread and wine into Christ's body and blood [by which] Christ becomes present in this sacrament", faith "in the efficacy of the Word of Christ and of the action of the Holy Spirit to bring about this conversion": "[B]y the consecration of the bread and wine there takes place a change of the whole substance of the bread into the substance of the body of Christ our Lord and of the whole substance of the wine into the substance of his blood. This change the holy Catholic Church has fittingly and properly called transubstantiation".[58]

As part of its own summary ("In brief") of the Catechism of the Catholic Church on the sacrament of the Eucharist, it states: "By the consecration the transubstantiation of the bread and wine into the Body and Blood of Christ is brought about. Under the consecrated species of bread and wine Christ himself, living and glorious, is present in a true, real, and substantial manner: his Body and his Blood, with his soul and his divinity (cf. Council of Trent: DS 1640; 1651)."[59]

The Church's teaching is given in the Compendium of the Catechism of the Catholic Church in question and answer form:

283. What is the meaning of transubstantiation? Transubstantiation means the change of the whole substance of bread into the substance of the Body of Christ and of the whole substance of wine into the substance of his Blood. This change is brought about in the eucharistic prayer through the efficacy of the word of Christ and by the action of the Holy Spirit. However, the outward characteristics of bread and wine, that is the “eucharistic species”, remain unaltered.[60]

The Anglican–Roman Catholic Joint Preparatory Commission stated in 1971 in their common declaration on Eucharistic doctrine: "The word transubstantiation is commonly used in the Roman Catholic Church to indicate that God acting in the eucharist effects a change in the inner reality of the elements."[17]

Opinions of some individuals (not necessarily typical)

In 2017 Irish Augustinian Gabriel Daly said that the Council of Trent approved use of the term "transubstantiation" as suitable and proper, but did not make it obligatory, and he suggested that its continued use is partly to blame for lack of progress towards sharing of the Eucharist between Protestants and Catholics.[61]

Traditionalist Catholic Paolo Pasqualucci said that the absence of the term in the Second Vatican Council's constitution on the liturgy Sacrosanctum Concilium means that it presents the Catholic Mass "in the manner of the Protestants". To this Dave Armstrong replied that "the word may not be present; but the concept is".[62] For instance, the document Gaudium et Spes refers to the "sacrament of faith where natural elements refined by man are gloriously changed into His Body and Blood, providing a meal of brotherly solidarity and a foretaste of the heavenly banquet" (Chapter 3).[63]

Thomas J. Reese commented that "using Aristotelian concepts to explain Catholic mysteries in the 21st century is a fool's errand", while Timothy O'Malley remarked that "it is possible to teach the doctrine of transubstantiation without using the words 'substance' and 'accidents'. If the word 'substance' scares people off, you can say, 'what it really is', and that is what substance is. What it really is, what it absolutely is at its heart is Christ's body and blood".[64]

General belief and doctrine knowledge among Catholics

A Georgetown University CARA poll of United States Catholics[65] in 2008 showed that 57% said they believed that Jesus Christ is really present in the Eucharist in 2008 and nearly 43% said that they believed the wine and bread are symbols of Jesus. Of those attending Mass weekly or more often, 91% believed in the Real Presence, as did 65% of those who merely attended at least once a month, and 40% of those who attended at most a few times a year.[66]

Among Catholics attending Mass at least once a month, the percentage of belief in the Real Presence was 86% for pre-Vatican II Catholics, 74% for Vatican II Catholics, 75% for post-Vatican II Catholics, and 85% for Millennials.[67]

A 2019 Pew Research Report found that 69% of United States Catholics believed that in the Eucharist the bread and wine "are symbols of the body and blood of Jesus Christ", and only 31% believed that, "during Catholic Mass, the bread and wine actually become the body and blood of Jesus". Of the latter group, most (28% of all US Catholics) said they knew that this is what the Church teaches, while the remaining 3% said they did not know it. Of the 69% who said the bread and wine are symbols, almost two-thirds (43% of all Catholics) said that what they believed is the Church's teaching, 22% said that they believed it in spite of knowing that the Church teaches that the bread and wine actually become the body and blood of Christ. Among United States Catholics who attend Mass at least once a week, the most observant group, 63% accepted that the bread and wine actually become the body and blood of Christ; the other 37% saw the bread and wine as symbols, most of them (23%) not knowing that the Church, so the survey stated, teaches that the elements actually become the body and blood of Christ, while the remaining 14% rejected what was given as the Church's teaching.[68] The Pew Report presented "the understanding that the bread and wine used in Communion are symbols of the body and blood of Jesus Christ" as contradicting belief that, “during Catholic Mass, the bread and wine actually become the body and blood of Jesus”.[68] The Catholic Church itself speaks of the bread and wine used in Communion both as "signs" and as "becoming" Christ's body and blood: "[...] the signs of bread and wine become, in a way surpassing understanding, the Body and Blood of Christ".[69]

In a comment on the Pew Research Report, Greg Erlandson drew attention to the difference between the formulation in the CARA survey, in which the choice was between "Jesus Christ is really present in the bread and wine of the Eucharist" and "the bread and wine are symbols of Jesus, but Jesus is not really present", and the Pew Research choice between "during Catholic Mass, the bread and wine actually become the body and blood of Jesus" and "the bread wine are symbols of the body and blood of Jesus Christ". He quotes an observation by Mark Gray that the word "actually" makes it sound like "something that could be analyzed under a microscope or empirically observed", while what the Church teaches is that the "substance" of the bread and wine are changed at consecration, but the "accidents" or appearances of bread and wine remain. Erlandson commented further: "Catholics may not be able to articulately define the 'Real Presence', and the phrase [sic] 'transubstantiation' may be obscure to them, but in their reverence and demeanor, they demonstrate their belief that this is not just a symbol".[70]

Theology

Catholic Church

.jpg.webp)

While the Catholic doctrine of transubstantiation in relation to the Eucharist can be viewed in terms of the Aristotelian distinction between substance and accident, Catholic theologians generally hold that, "in referring to the Eucharist, the Church does not use the terms substance and accident in their philosophical contexts but in the common and ordinary sense in which they were first used many centuries ago. The dogma of transubstantiation does not embrace any philosophical theory in particular."[72] This ambiguity is recognized also by a Lutheran theologian such as Jaroslav Pelikan, who, while himself interpreting the terms as Aristotelian, states that "the application of the term 'substance' to the discussion of the Eucharistic presence antedates the rediscovery of Aristotle. [...] Even 'transubstantiation' was used during the twelfth century in a nontechnical sense. Such evidence lends credence to the argument that the doctrine of transubstantiation, as codified by the decrees of the Fourth Lateran and Tridentine councils, did not canonize Aristotelian philosophy as indispensable to Christian doctrine. But whether it did so or not in principle, it has certainly done so in effect".[73]

The view that the distinction is independent of any philosophical theory has been expressed as follows: "The distinction between substance and accidents is real, not just imaginary. In the case of the person, the distinction between the person and his or her accidental features is after all real. Therefore, even though the notion of substance and accidents originated from Aristotelian philosophy, the distinction between substance and accidents is also independent of philosophical and scientific development."[74] "Substance" here means what something is in itself: take some concrete object – e.g. your own hat. The shape is not the object itself, nor is its color, size, softness to the touch, nor anything else about it perceptible to the senses. The object itself (the "substance") has the shape, the color, the size, the softness and the other appearances, but is distinct from them. While the appearances are perceptible to the senses, the substance is not.[75]

The philosophical term "accidents" does not appear in the teaching of the Council of Trent on transubstantiation, which is repeated in the Catechism of the Catholic Church.[76] For what the Council distinguishes from the "substance" of the bread and wine it uses the term species:

The Council of Trent summarizes the Catholic faith by declaring: "Because Christ our Redeemer said that it was truly his body that he was offering under the species of bread, it has always been the conviction of the Church of God, and this holy Council now declares again, that by the consecration of the bread and wine there takes place a change of the whole substance of the bread into the substance of the body of Christ our Lord and of the whole substance of the wine into the substance of his blood. This change the holy Catholic Church has fittingly and properly called transubstantiation."[77]

The Catechism of the Catholic Church cites the Council of Trent also in regard to the mode of the real presence of Christ in the Eucharist:

In the most blessed sacrament of the Eucharist "the body and blood, together with the soul and divinity, of our Lord Jesus Christ and, therefore, the whole Christ is truly, really, and substantially contained." (Council of Trent (1551): DS 1651) "This presence is called 'real' – by which is not intended to exclude the other types of presence as if they could not be 'real' too, but because it is presence in the fullest sense: that is to say, it is a substantial presence by which Christ, God and man, makes himself wholly and entirely present." (Paul VI, MF 39).[78]: 1374

The Catholic Church holds that the same change of the substance of the bread and of the wine at the Last Supper continues to occur at the consecration of the Eucharist[78]: 1377 [79] when the words are spoken in persona Christi "This is my body ... this is my blood." In Orthodox confessions, the change is said to start during the Dominical or Lord's Words or Institution Narrative and be completed during the Epiklesis.[80]

Teaching that Christ is risen from the dead and is alive, the Catholic Church holds, in addition to the doctrine of transubstantiation, that when the bread is changed into his body, not only his body is present, but Christ as a whole is present ("the body and blood, together with the soul and divinity"). The same holds when the wine is transubstantiated into the blood of Christ.[78] This is known as the doctrine of concomitance.

In accordance with the dogmatic teaching that Christ is really, truly and substantially present under the appearances of bread and wine, and continues to be present as long as those appearances remain, the Catholic Church preserves the consecrated elements, generally in a church tabernacle, for administering Holy Communion to the sick and dying.

In the arguments which characterised the relationship between Roman Catholicism and Protestantism in the 16th century, the Council of Trent declared subject to the ecclesiastical penalty of anathema anyone who

denieth, that, in the sacrament of the most holy Eucharist, are contained truly, really, and substantially, the body and blood together with the soul and divinity of our Lord Jesus Christ, and consequently the whole Christ; but saith that He is only therein as in a sign, or in figure, or virtue [... and anyone who] saith, that, in the sacred and holy sacrament of the Eucharist, the substance of the bread and wine remains conjointly with the body and blood of our Lord Jesus Christ, and denieth that wonderful and singular conversion of the whole substance of the bread into the Body, and of the whole substance of the wine into the Blood – the species only of the bread and wine remaining – which conversion indeed the Catholic Church most aptly calls Transubstantiation, let him be anathema.

— Council of Trent, quoted in J. Waterworth (ed.), The Council of Trent: The Thirteenth Session[55]

The Catholic Church asserts that the consecrated bread and wine are not merely "symbols" of the body and blood of Christ: they are the body and blood of Christ.[81] It also declares that, although the bread and wine completely cease to be bread and wine (having become the body and blood of Christ), the appearances (the "species" or look) remain unchanged, and the properties of the appearances also remain (one can be drunk with the appearance of wine despite it only being an appearance). They are still the appearances of bread and wine, not of Christ, and do not inhere in the substance of Christ. They can be felt and tasted as before, and are subject to change and can be destroyed. If the appearance of bread is lost by turning to dust or the appearance of wine is lost by turning to vinegar, Christ is no longer present.[82][83]

The essential signs of the Eucharistic sacrament are wheat bread and grape wine, on which the blessing of the Holy Spirit is invoked and the priest pronounces the words of consecration spoken by Jesus during the Last Supper: "This is my body which will be given up for you. ... This is the cup of my blood ..."[84] When the signs cease to exist, so does the sacrament.[85]

According to Catholic teaching, the whole of Christ, body and blood, soul and divinity, is really, truly and substantially in the sacrament, under each of the appearances of bread and wine, but he is not in the sacrament as in a place and is not moved when the sacrament is moved. He is perceptible neither by the sense nor by the imagination, but only by the intellectual eye.[86]

St. Thomas Aquinas gave poetic expression to this perception in the devotional hymn Adoro te devote:

Godhead here in hiding, whom I do adore,

Masked by these bare shadows, shape and nothing more,

See, Lord, at thy service low lies here a heart

Lost, all lost in wonder at the God thou art.

Seeing, touching, tasting are in thee deceived:

How says trusty hearing? that shall be believed.

What God's Son has told me, take for truth I do;

Truth himself speaks truly or there's nothing true.

An official statement from the Anglican–Roman Catholic International Commission titled Eucharistic Doctrine, published in 1971, states that "the word transubstantiation is commonly used in the Roman Catholic Church to indicate that God acting in the Eucharist effects a change in the inner reality of the elements. The term should be seen as affirming the fact of Christ's presence and of the mysterious and radical change which takes place. In Roman Catholic theology it is not understood as explaining how the change takes place."[87] In the smallest particle of the host or the smallest droplet from the chalice Jesus Christ himself is present: "Christ is present whole and entire in each of the species and whole and entire in each of their parts, in such a way that the breaking of the bread does not divide Christ."[88]

Eastern Christianity

As the Disputation of the Holy Sacrament took place in the Western Church after the Great Schism, the Eastern Churches remained largely unaffected by it. The debate on the nature of "transubstantiation" in Greek Orthodoxy begins in the 17th century, with Cyril Lucaris, whose The Eastern Confession of the Orthodox Faith was published in Latin in 1629. The Greek term metousiosis (μετουσίωσις) is first used as the translation of Latin transubstantiatio in the Greek edition of the work, published in 1633.

The Eastern Catholic, Oriental Orthodox and Eastern Orthodox Churches, along with the Assyrian Church of the East, agree that in a valid Divine Liturgy bread and wine truly and actually become the body and blood of Christ. In Orthodox confessions, the change is said to start during the Liturgy of Preparation and be completed during the Epiklesis. However, there are official church documents that speak of a "change" (in Greek μεταβολή) or "metousiosis" (μετουσίωσις) of the bread and wine. "Μετ-ουσί-ωσις" (met-ousi-osis) is the Greek word used to represent the Latin word "trans-substanti-atio",[89][90] as Greek "μετα-μόρφ-ωσις" (meta-morph-osis) corresponds to Latin "trans-figur-atio". Examples of official documents of the Eastern Orthodox Church that use the term "μετουσίωσις" or "transubstantiation" are the Longer Catechism of The Orthodox, Catholic, Eastern Church (question 340)[91] and the declaration by the Eastern Orthodox Synod of Jerusalem of 1672:

In the celebration of [the Eucharist] we believe the Lord Jesus Christ to be present. He is not present typically, nor figuratively, nor by superabundant grace, as in the other Mysteries, nor by a bare presence, as some of the Fathers have said concerning Baptism, or by impanation, so that the Divinity of the Word is united to the set forth bread of the Eucharist hypostatically, as the followers of Luther most ignorantly and wretchedly suppose. But [he is present] truly and really, so that after the consecration of the bread and of the wine, the bread is transmuted, transubstantiated, converted and transformed into the true Body Itself of the Lord, Which was born in Bethlehem of the ever-Virgin, was baptized in the Jordan, suffered, was buried, rose again, was received up, sits at the right hand of the God and Father, and is to come again in the clouds of Heaven; and the wine is converted and transubstantiated into the true Blood Itself of the Lord, Which as He hung upon the Cross, was poured out for the life of the world.[92]

The way in which the bread and wine become the body and blood of Christ has never been dogmatically defined by the Eastern Orthodox Churches. However, St Theodore the Studite writes in his treatise "On the Holy Icons": "for we confess that the faithful receive the very body and blood of Christ, according to the voice of God himself."[93] This was a refutation of the iconoclasts, who insisted that the eucharist was the only true icon of Christ. Thus, it can be argued that by being part of the dogmatic "horos" against the iconoclast heresy, the teaching on the "real presence" of Christ in the eucharist is indeed a dogma of the Eastern Orthodox Church.

Anglicanism

Transubstantiation is generally rejected in Anglicanism.

Elizabeth I gave royal assent to the 39 Articles. The Articles declared that "Transubstantiation (or the change of the substance of Bread and Wine) in the Supper of the Lord, cannot be proved by holy Writ; but is repugnant to the plain words of Scripture, overthroweth the nature of a Sacrament, and hath given occasion to many superstitions." The Elizabethan Settlement accepted the Real Presence of Christ in the Sacrament, but refused to define it, preferring to leave it a mystery. Indeed, for many years it was illegal in Britain to hold public office whilst believing in transubstantiation, as under the Test Act of 1673. Archbishop John Tillotson decried the "real barbarousness of this Sacrament and Rite of our Religion", considering it a great impiety to believe that people who attend Holy Communion "verily eat and drink the natural flesh and blood of Christ. And what can any man do more unworthily towards a Friend? How can he possibly use him more barbarously, than to feast upon his living flesh and blood?" (Discourse against Transubstantiation, London 1684, 35). In the Church of England today, clergy are required to assent that the 39 Articles have borne witness to the Christian faith.[94]

The Eucharistic teaching labeled "receptionism", defined by Claude Beaufort Moss as "the theory that we receive the Body and Blood of Christ when we receive the bread and wine, but they are not identified with the bread and wine which are not changed",[95] was commonly held by 16th and 17th-century Anglican theologians. It was characteristic of 17th century thought to "insist on the real presence of Christ in the Eucharist, but to profess agnosticism concerning the manner of the presence". It remained "the dominant theological position in the Church of England until the Oxford Movement in the early nineteenth century, with varying degrees of emphasis". Importantly, it is "a doctrine of the real presence" but one which "relates the presence primarily to the worthy receiver rather than to the elements of bread and wine".[96]

Anglicans generally consider no teaching binding that, according to the Articles, "cannot be found in Holy Scripture or proved thereby", and are not unanimous in the interpretation of such passages as John 6[97] and 1 Corinthians 11,[98] although all Anglicans affirm a view of the real presence of Christ in the Eucharist: some Anglicans (especially Anglo-Catholics and some other High Church Anglicans) hold to a belief in the corporeal presence while Evangelical Anglicans hold to a belief in the pneumatic presence. As with all Anglicans, Anglo-Catholics and other High Church Anglicans historically held belief in the real presence of Christ in the Eucharist but were "hostile to the doctrine of transubstantiation".[99][100]

However, in the first half of the twentieth century, the Catholic Propaganda Society upheld both Article XXVIII and the doctrine of transubstantiation, stating that the 39 Articles specifically condemn a pre-Council of Trent "interpretation which was included by some under the term Transubstantiation" in which "the bread and wine were only left as a delusion of the senses after consecration";[101] it stated that "this Council propounded its definition after the Articles were written, and so cannot be referred to by them".[101]

Theological dialogue with the Roman Catholic Church has produced common documents that speak of "substantial agreement" about the doctrine of the Eucharist: the ARCIC Windsor Statement of 1971,[102] and its 1979 Elucidation.[103] Remaining arguments can be found in the Church of England's pastoral letter: The Eucharist: Sacrament of Unity.[104]

Lutheranism

Lutherans explicitly reject transubstantiation[105] believing that the bread and wine remain fully bread and fully wine while also being truly the body and blood of Jesus Christ.[106][107][108][109] Lutheran churches instead emphasize the sacramental union[110] (not exactly the consubstantiation, as is often claimed)[111] and believe that within the Eucharistic celebration the body and blood of Jesus Christ are objectively present "in, with, and under the forms" of bread and wine (cf. Book of Concord).[106] They place great stress on Jesus's instructions to "take and eat", and "take and drink", holding that this is the proper, divinely ordained use of the sacrament, and, while giving it due reverence, scrupulously avoid any actions that might indicate or lead to superstition or unworthy fear of the sacrament.[107]

In dialogue with Catholic theologians, a large measure of agreement has been reached by a group of Lutheran theologians. They recognize that "in contemporary Catholic expositions, ... transubstantiation intends to affirm the fact of Christ's presence and of the change which takes place, and is not an attempt to explain how Christ becomes present. ... [And] that it is a legitimate way of attempting to express the mystery, even though they continue to believe that the conceptuality associated with "transubstantiation" is misleading and therefore prefer to avoid the term."[112]

Reformed churches

Classical Presbyterianism held Calvin's view of "pneumatic presence" or "spiritual feeding", a Real Presence by the Spirit for those who have faith. John Calvin "can be regarded as occupying a position roughly midway between" the doctrines of Martin Luther on one hand and Huldrych Zwingli on the other. He taught that "the thing that is signified is effected by its sign", declaring: "Believers ought always to live by this rule: whenever they see symbols appointed by the Lord, to think and be convinced that the truth of the thing signified is surely present there. For why should the Lord put in your hand the symbol of his body, unless it was to assure you that you really participate in it? And if it is true that a visible sign is given to us to seal the gift of an invisible thing, when we have received the symbol of the body, let us rest assured that the body itself is also given to us."[113]

The Westminster Shorter Catechism summarises the teaching:

Q. What is the Lord's supper? A. The Lord's supper is a sacrament, wherein, by giving and receiving bread and wine according to Christ's appointment, his death is showed forth; and the worthy receivers are, not after a corporal and carnal manner, but by faith, made partakers of his body and blood, with all his benefits, to their spiritual nourishment and growth in grace.[114]

Methodism

Methodists believe in the real presence of Christ in the bread and wine (or grape juice) while, like Anglicans, Presbyterians and Lutherans, rejecting transubstantiation. According to the United Methodist Church, "Jesus Christ, who 'is the reflection of God's glory and the exact imprint of God's very being',[115] is truly present in Holy Communion."[116]

While upholding the view that scripture is the primary source of Church practice, Methodists also look to church tradition and base their beliefs on the early Church teachings on the Eucharist, that Christ has a real presence in the Lord's Supper. The Catechism for the use of the people called Methodists thus states that, "[in Holy Communion] Jesus Christ is present with his worshipping people and gives himself to them as their Lord and Saviour".[117]

Others

The act of consumption of perceived flesh and blood by Catholics has been compared to the rituals of cannibal Native Americans by modern scholars of religion, both in significance and in objects of the ritual.[118]

See also

References

Notes

- "Compendium of the Catechism of the Catholic Church". vatican.va.

- "The Eucharist: What is the Eucharist?". www.usccb.org. Retrieved March 17, 2023.

- "Liturgy of the Eucharist: Eucharistic Prayer". www.usccb.org. Retrieved March 17, 2023.

- McNamara, Edward. "Liturgy Q & A: On Transubstantiation". www.zenit.org. Retrieved March 17, 2023.

- "Liturgy Q & A: On Transubstantiation". Zenit. April 19, 2016.

- Fay, William (2001). "The Real Presence of Jesus Christ in the Sacrament of the Eucharist: Basic Questions and Answers". United States Conference of Catholic Bishops. Retrieved 13 December 2015.

the Catholic Church professes that, in the celebration of the Eucharist, bread and wine become the Body and Blood of Jesus Christ through the power of the Holy Ghost and the instrumentality of the priest.

- "Internet History Sourcebooks Project". sourcebooks.fordham.edu.

- "Lateran Council | Roman Catholicism". Encyclopedia Britannica.

- Hillebrand, Hans J., ed. (2005). "Transubstantiation". The Oxford Encyclopedia of the Reformation. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-506493-3. Retrieved 2017-05-30.

- "Catechism of the Catholic Church – The sacrament of the Eucharist, 1333". vatican.va. Archived from the original on 2020-02-04. Retrieved 2020-01-05.

- Voigt, A. G. (1917). Biblical Dogmatics. Press of Lutheran Board of Publication. p. 215.

- Bradshaw, Paul F. (2012). The Eucharistic liturgies : their evolution and interpretation. Maxwell E. Johnson. Collegeville, Minn. ISBN 978-0-8146-6266-3. OCLC 957998003.

The Catholic Mass expects God to work a transformation, a change of the elements of bread and wine into the very presence of Christ. The Anglican prayers do not demand this objective change in the elements: they ask merely that the bread and wine should now take on new significance for us, as symbols of His Body and Blood. In fact, the Anglican formulae will bear interpretation either way. This is a deliberate policy, and part of the genius of Anglicanism, its ability to accommodate contradictory doctrines under the same outward form of words.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - "Philip Schaff: NPNF2-05. Gregory of Nyssa: Dogmatic Treatises, Etc. – Christian Classics Ethereal Library". ccel.org. Retrieved 2021-11-11.

- "Church Fathers: Catechetical Lecture 23 (Cyril of Jerusalem)". newadvent.org. Retrieved 2021-11-11.

- "Philip Schaff: NPNF2-09. Hilary of Poitiers, John of Damascus – Christian Classics Ethereal Library". ccel.org. Retrieved 2021-11-11.

- "Sermon 234". Fathers Of The Church. 1959.

- "Anglican – Roman Catholic Joint Preparatory Commission, Agreed Statement on Eucharistic Doctrine 1971" (PDF).

- "Catholic Encyclopedia: Early Symbols of the Eucharist". Retrieved 2017-05-31.

- "Church Fathers: Ignatius to the Smyrnaeans". earlychristianwritings.com. Retrieved 2017-11-12.

- "Church Fathers: On the Mysteries (St. Ambrose)". newadvent.org.

- "The Didache". earlychristianwritings.com. Retrieved 2017-11-12.

- "Ignatius to the Romans". earlychristianwritings.com. Retrieved 2017-11-12.

- "Saint Justin Martyr: First Apology (Roberts-Donaldson)". earlychristianwritings.com. Retrieved 2017-11-12.

- "Church Fathers: Against Marcion, Book IV (Tertullian)". newadvent.org.

- "ANF07. Fathers of the Third and Fourth Centuries: Lactantius, Venantius, Asterius, Victorinus, Dionysius, Apostolic Teaching and Constitutions, Homily – Christian Classics Ethereal Library". ccel.org.

- Cyril of Jerusalem, Cat. Myst., 5, 7 (Patrologia Graeca 33:1113): μεταβολή

- Gregory of Nyssa, Oratio catechetica magna, 37 (PG 45:93): μεταστοιχειώσας

- John Chrysostom, Homily 1 on the betrayal of Judas, 6 (PG 49:380): μεταρρύθμησις

- Cyril of Alexandria, On Luke, 22, 19 (PG 72:911): μετίτησις

- John Damascene, On the orthodox faith, book 4, chapter 13 (PG 49:380): μεταποίησις

- Sermons (230-272B) on the Liturgical Seasons (New City Press 1994), p. 37; original text in Migne, Patrologia latina, vol. 38, col. 1116

- Willis, Wendell (2017-01-06). Eucharist and Ecclesiology: Essays in Honor of Dr. Everett Ferguson. Wipf and Stock Publishers. ISBN 978-1-4982-8292-5.

- Pohle, J. (1909). "The Real Presence of Christ in the Eucharist". New Advent.

- Chazelle, pg. 9

- Chazelle, pg. 10

- Oxford Dictionary of the Christian Church (Oxford University Press 2005 ISBN 978-0-19-280290-3), article Berengar of Tours

- John Cuthbert Hedley, Holy Eucharist (1907), p. 37. John N. King, Milton and Religious Controversy (Cambridge University Press 2000 ISBN 978-0-52177198-6), p. 134

- Oxford Dictionary of the Christian Church (Oxford University Press 2005 ISBN 978-0-19-280290-3), article Transubstantiation

-

Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). "Fourth Lateran Council (1215)". Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company..

of Faith Fourth Lateran Council: 1215, 1. Confession of Faith, retrieved 2010-03-13.

Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). "Fourth Lateran Council (1215)". Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company..

of Faith Fourth Lateran Council: 1215, 1. Confession of Faith, retrieved 2010-03-13. - "Internet History Sourcebooks Project". sourcebooks.fordham.edu.

- Javis, Matthew (2013). "Councils of Faith: Lateran IV (1215)". Dominican Friars.

- Ryan, S. and Shanahan, A. (2018) How to communicate Lateran IV in 13th century Ireland: lessons from the Liber Examplorum (c. 1275). Religions 9(3): 75; https://doi.org/10.3390/rel9030075

- Boyle, Leonard E. (October 1, 1979). Robert Grosseteste and the Transubstantiation. p. 512. doi:10.1093/jts/XXX.2.512.

{{cite book}}:|journal=ignored (help) - Adams, Marylin (2012). Some later medieval theories of the Eucharist: Thomas Aquinas, Gilles of Rome, Duns Scotus, and William Ockham. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780199658169.

- Stephen E. Lahey, "Review of Adams, Some later medieval theories ..." in The Journal of Ecclesiastical History, vol. 63, issue 1 (January 2012)

- Luther, M. The Babylonian Captivity of the Christian Church. 1520. Quoted in, McGrath, A. 1998. Historical Theology, An Introduction to the History of Christian Thought. Blackwell Publishers: Oxford. p. 198.

- McGrath, op.cit. pp. 198-99

- McGrath, op.cit., p197.

- "A Prelude by Martin Luther on the Babylonian Captivity of the Church, 2:26 & 2:27". Archived from the original on 2009-06-18.

- Weimar Ausgabe 26, 442; Luther's Works 37, 299–300.

- Thirty-Nine Articles, article 28

- "Penal Laws | British and Irish history". Encyclopedia Britannica.

- "Factbox: Catholicism in Britain". Reuters. September 13, 2010 – via reuters.com.

- "The Council of Trent, Thirteenth Session, canon 1: "If any one denieth, that, in the sacrament of the most holy Eucharist, are contained truly, really, and substantially, the body and blood together with the soul and divinity of our Lord Jesus Christ, and consequently the whole Christ; but saith that He is only therein as in a sign, or in figure, or virtue; let him be anathema."".

- Waterworth, J. (ed.). "The Council of Trent – The Thirteenth Session". Scanned by Hanover College students in 1995 (1848 ed.). London: Dolman.

- "Transubstantiation". Encyclopædia Britannica.

- Davis, Charles (April 1, 1964). "The theology of transubstantiation". Sophia. 3 (1): 12–24. doi:10.1007/BF02785911. S2CID 170618935.

- "Catechism of the Catholic Church – IntraText". vatican.va.

- "Catechism of the Catholic Church - IntraText". www.vatican.va.

- "Compendium of the Catechism of the Catholic Church". vatican.va.

- "Catholics should 'stop talking' of transubstantiation". The Tablet. Retrieved 2019-12-31.

- "Vs. Pasqualucci Re Vatican II #11: SC & Sacrifice of the Mass". Biblical Evidence for Catholicism. 2019-07-22. Retrieved 2019-12-31.

- "Vatican II and the Eucharist". therealpresence.org. Retrieved 2020-01-03.

- "The Real Presence: What do Catholics believe and how can the Churchrespond? | Southern Cross Online Edition". southerncross.diosav.org. Retrieved 2020-01-02.

- "CARA Catholic Poll Methods".

- "CARA Catholic Poll: "Sacraments Today: Belief and Practice among U.S. Catholics", p. 54" (PDF).

- CARA Catholic Poll: "Sacraments Today: Belief and Practice among U.S. Catholics", p. 55: "Among Catholics attending Mass at least once a month, Millennial Generation Catholics are just as likely as Pre-Vatican II Catholics to agree that Jesus is really present in the Eucharist (85 percent compared to 86 percent). Vatican II and Post-Vatican II Generation Catholics are about 10 percentage points less likely to believe that Christ is really present in the Eucharist (74 and 75 percent, respectively)." Indicated also in the diagram on the same page.

- "Just one-third of U.S. Catholics agree with their church that Eucharist is body, blood of Christ". Pew Research Center. August 5, 2019. Retrieved 2020-01-01.

- "Catechism of the Catholic Church – IntraText". vatican.va. Retrieved 2020-09-18.

- "Do we really believe in the Real Presence?". The Boston Pilot. Retrieved 2020-01-01.

- Adams, Italian Renaissance Art, p. 345f.

- "Edward McNamara, "On Transubstantiation" in ZENIT, 19 April 2016".

- Pelikan, Jaroslav (1971). The Christian Tradition: A History of the Development of Doctrine, Volume 1: The Emergence of the Catholic Tradition (100–600). University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0226653716 – via Google Books.

- Paul Haffner, The Sacramental Mystery (Gracewing Publishing 1999 ISBN 978-0852444764), p. 92

- "Catholic Evidence Training Outlines – Google Books". 1934.

- There were two editions of the Catechism of the Catholic Church in the 1990s. The first was issued in French in 1992, the second in Latin in 1997. Each was soon translated into English.

- "Catechism of the Catholic Church – The sacrament of the Eucharist". vatican.va.

- "V. The Sacramental Sacrifice Thanksgiving, Memorial, Presence". Catechism of the Catholic Church. Libreria Editrice Vaticana.

- Dulles, Avery (15 April 2005). "Christ's Presence in the Eucharist: True, Real and Substantial". Archived from the original on 9 July 2017. Retrieved 31 May 2017.

- Kappes, Christiaan (2017). "The Epiclesis Debate: Mark of Ephesus and John Torquemada, OP, at the Council of Florence 1439". University of Notre Dame Press.

- "The Real Presence of Jesus Christ in the Sacrament of the Eucharist: Basic Questions and Answers". usccb.org.

- "Tour of the Summa | Precis of the Summa Theologica of St Thomas Aquinas | Msgr P Glenn". catholictheology.info. Retrieved 2019-09-25.

- "Summa Theologiae: The accidents which remain in this sacrament (Tertia Pars, Q. 77)". newadvent.org. Retrieved 2019-09-25.

- "Catechism of the Catholic Church – IntraText". vatican.va. Retrieved 2019-09-25.

- "[I]f the change be so great that the substance of the bread or wine would have been corrupted, then Christ's body and blood do not remain under this sacrament; and this either on the part of the qualities, as when the color, savor, and other qualities of the bread and wine are so altered as to be incompatible with the nature of bread or of wine; or else on the part of the quantity, as, for instance, if the bread be reduced to fine particles, or the wine divided into such tiny drops that the species of bread or wine no longer remain" (Thomas Aquinas, Summa Theologica, III, q. 77, art. 4).

- "Summa Theologica: TREATISE ON THE SACRAMENTS (QQ[60]-90): Question. 76 – OF THE WAY IN WHICH CHRIST IS IN THIS SACRAMENT (EIGHT ARTICLES)". sacred-texts.com. Retrieved 2019-09-25.

- Douglas, Brian (2015). The Eucharistic Theology of Edward Bouverie Pusey: Sources, Context and Doctrine within the Oxford Movement and Beyond. Brill. p. 139. ISBN 978-9004304598.

- Catechism of the Catholic Church, 1356–1381, number 1377, cf. Council of Trent: DS 1641: "Nor should it be forgotten that Christ, whole and entire, is contained not only under either species, but also in each particle of either species. 'Each,' says St. Augustine, 'receives Christ the Lord, and He is entire in each portion. He is not diminished by being given to many, but gives Himself whole and entire to each.'" (Quoted in Gratian, p. 3, dist. ii. c. 77; Ambrosian Mass, Preface for Fifth Sunday after Epiph.) The Catechism of the Council of Trent for Parish Priests, issued by order of Pope Pius V, translated into English with Notes by John A. McHugh, O.P., S.T.M., Litt. D., and Charles J. Callan, O.P., S.T.M., Litt. D., (1982) TAN Books and Publishers, Inc., Rockford, Ill. ISBN 978-0-89555-185-6. p. 249 "Christ Whole and Entire Present in Every Part of Each Species".

- "Creeds of Christendom, with a History and Critical notes. Volume I. The History of Creeds. – Christian Classics Ethereal Library". ccel.org. Archived from the original on 2017-11-14. Retrieved 2010-09-06.

- "The Holy Orthodox Church at the Synod of Jerusalem (date 1643 A.D.) used the word metousiosis—a change of ousia—to translate the Latin Transsubstantiatio" (Transubstantiation and the Black Rubric).

- "The Longer Catechism of The Orthodox, Catholic, Eastern Church". pravoslavieto.com. Retrieved 2020-06-04.

- Confession of Dositheus Archived 2009-02-21 at the Wayback Machine (emphasis added) The Greek text is quoted in an online extract Archived 2011-07-21 at the Wayback Machine from the 1915 book "Μελέται περί των Θείων Μυστηρίων" (Studies on the Divine Mysteries/Sacraments) by Saint Nektarios.

- [Catharine Roth, St. Theodore the Studite, On the Holy Icons, Crestwood 1981, 30.]

- "Common Worship". cofe.anglican.org. Archived from the original on 2008-08-08. Retrieved 2008-10-17.

- Claude B. Moss, The Christian Faith: An Introduction to Dogmatic Theology (London: SPCK 1943), p. 366, cited in Brian Douglas, A Companion to Anglican Eucharistic Theology (Brill 2012), vol. 2, p. 181

- Crockett, William R. (1988). "Holy Communion". In Sykes, Stephen; Booty, John. The Study of Anglicanism. Philadelphia: SPCK/Fortress Press. p. 275. ISBN 978-0800620875

- John 6

- 1 Corinthians 11

- Poulson, Christine (1999). The Quest for the Grail: Arthurian Legend in British Art, 1840–1920. Manchester University Press. p. 40. ISBN 978-0719055379.

By the late 1840s Anglo-Catholic interest in the revival of ritual had given new life to doctrinal debate over the nature of the Eucharist. Initially, 'the Tractarians were concerned only to exalt the importance of the sacrament and did not engage in doctrinal speculation'. Indeed they were generally hostile to the doctrine of transubstantiation. For an orthodox Anglo-Catholic such as Dyce the doctrine of the Real Presence was acceptable, but that of transubstantiation was not.

- Spurr, Barry (2010). Anglo-Catholic in Religion. Lutterworth Press. p. 100. ISBN 978-0718830731.

The doctrine had been affirmed by Anglican theologians, through the ages, including Lancelot Andrewes, Jeremy Taylor (who taught the doctrine of the Real Presence at the eucharist, but attacked Roman transubstantiation), William Laud and John Cosin – all in the seventeenth century – as well as in the nineteenth century Tractarians and their successors.

- "Transubstantiation and the Black Rubric". anglicanhistory.org.

- "Pro Unione Web Site – Full Text ARCIC Eucharist". prounione.urbe.it. Archived from the original on 2018-10-17. Retrieved 2006-01-03.

- "Pro Unione Web Site – Full Text ARCIC Elucidation Eucharist". prounione.urbe.it. Archived from the original on 2018-10-08. Retrieved 2006-01-03.

- "Council for Christian Unity" (PDF). cofe.anglican.org. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2006-02-18. Retrieved 2006-01-03.

- Luther, Martin (1537), Smalcald Articles, Part III, Article VI. Of the Sacrament of the Altar, stating: "As regards transubstantiation, we care nothing about the sophistical subtlety by which they teach that bread and wine leave or lose their own natural substance, and that there remain only the appearance and color of bread, and not true bread. For it is in perfect agreement with Holy Scriptures that there is, and remains, bread, as Paul himself calls it, 1 Cor. 10:16: The bread which we break. And 1 Cor. 11:28: Let him so eat of that bread."

- Brug, J.F. (1998), The Real Presence of Christ's Body and Blood in The Lord's Supper:: Contemporary Issues Concerning the Sacramental Union Archived 2015-02-04 at the Wayback Machine, pp. 2–4

- Schuetze, A.W. (1986), Basic Doctrines of the Bible (Milwaukee: Northwestern Publishing House), Chapter 12, Article 3

- "Real Presence: What is really the difference between "transubstantiation" and "consubstantiation"?". WELS Topical Q&A. Wisconsin Evangelical Lutheran Synod. Archived from the original on 28 September 2009. Retrieved 25 July 2016.

We reject transubstantiation because the Bible teaches that the bread and the wine are still present in the Lord's Supper (1 Corinthians 10:16, 1 Corinthians 11:27–28). We do not worship the elements because Jesus commands us to eat and to drink the bread and the wine. He does not command us to worship them.

- "Real Presence: Why not Transubstantiation?". WELS Topical Q&A. Wisconsin Evangelical Lutheran Synod. Archived from the original on 28 September 2009. Retrieved 25 July 2016.

- VII. The Lord's Supper: Affirmative Theses, Epitome of the Formula of Concord, 1577, stating that: "We believe, teach, and confess that the body and blood of Christ are received with the bread and wine, not only spiritually by faith, but also orally; yet not in a Capernaitic, but in a supernatural, heavenly mode, because of the sacramental union"

- "Real Presence Communion – Consubstantiation?". WELS Topical Q&A. Wisconsin Evangelical Lutheran Synod. Archived from the original on 27 September 2009. Retrieved 25 July 2016.

Although some Lutherans have used the term 'consbstantiation' [sic] and it might possibly be understood correctly (e.g., the bread & wine, body & blood coexist with each other in the Lord's Supper), most Lutherans reject the term because of the false connotation it contains ... either that the body and blood, bread and wine come together to form one substance in the Lord's Supper or that the body and blood are present in a natural manner like the bread and the wine. Lutherans believe that the bread and the wine are present in a natural manner in the Lord's Supper and Christ's true body and blood are present in an illocal, supernatural manner.

- "The Eucharist". usccb.org. Retrieved 2019-09-25.

- McGrath, op.cit., p.199.

- Westminster Shorter Catechism, Q&A 96

- Hebrews 1:3

- "This Holy Mystery: Part Two". The United Methodist Church GBOD. Archived from the original on July 7, 2009. Retrieved 30 May 2013.

- A Catechism for the use of people called Methodists. Peterborough, England: Methodist Publishing House. 2000. p. 26. ISBN 978-1858521824.

- Cevasco, Carla. "This is My Body: Communion and Cannibalism in Colonial New England and New France" (Document).

Scholars of religion in the Atlantic world have pointed to similarities between various Indian groups' ritual cannibalism and Protestant and Catholic communion

{{cite document}}: Cite document requires|publisher=(help)

Bibliography

- Burckhardt Neunheuser, "Transsubstantiation." Lexikon für Theologie und Kirche, vol. 10, cols. 311–314.

- Miri Rubin, Corpus Christi: The Eucharist in Late Medieval Culture (1991), pp. 369–419.

- Otto Semmelroth, Eucharistische Wandlung: Transsubstantation, Transfinalisation, Transsignifikation (Kevelaer: Butzon & Bercker, 1967).

- Richard J. Utz and Christine Batz, "Transubstantiation in Medieval and Early Modern Culture and Literature: An Introductory Bibliography of Critical Studies", in: Translation, Transformation, and Transubstantiation, ed. Carol Poster and Richard Utz (Evanston: IL: Northwestern University Press, 1998), pp. 223–256."